The newly reunified Germany was not only a physical construction site but also an enormous social and cultural laboratory—often a painful one. »Wir sind ein Volk«, sure, »We are one people, but we hardly know each other.« And thirty-five years later, this observation remains partly true. This Germany is not the "Year Zero" Germany of the post-war period, but once again must define —through radical choices— its role in Europe and the world.

Between 1945 and 1955, it was a question of coming to terms with the past, making amends and drawing lines. In the early 1990s, it was a question of demonstrating, especially to its European neighbours, that there was nothing to fear from a reunified Germany: a country aware of its past and committed to a European future.

But which past? The two Germanies brought different, problematic memories to reunification: West Germany had confronted its history through political conflicts, historians' debates and a social revolution led by generations who broke the silence - even at the cost of challenging the state itself. East Germany's memory was built on a state-sponsored anti-fascism that had erased both colonial and Nazi history from its books, treating it as the history of West Germans only, while erecting grand Soviet monuments in its place.

Beneath this unspoken history, something darker was stirring: neo-Nazism and violent xenophobia emerged to mark the early years of reunification. In 2021 and 2022, the German media - led by state television news - highlighted the commemoration of the thirtieth anniversary of the first xenophobic attacks in reunified Germany: the 1991 Hoyerswerda pogrom in Saxony, where a mob of right-wing extremists and local residents attacked a hostel housing contract workers from Mozambique and Vietnam; and the 1992 Rostock-Lichtenhagen incident, one of the most violent racist attacks in post-war Germany, which targeted an apartment building housing Vietnamese migrants and asylum seekers. However, similar neo-Nazi xenophobic attacks also occurred in western Germany during this period, notably in Mölln (1992) and Solingen (1993). Foreign media observers found this emerging pattern in Germany deeply troubling.

All of Europe was in a state of flux and turmoil. The re-emergence of the Eastern Bloc countries after the Cold War set in motion a new examination of European memory - one that revealed uncomfortable truths. While it had been convenient to blame all crimes against humanity solely on the Germans, the opening of archives revealed extensive local collaboration, massacres of minorities and inter-ethnic violence across the continent. This revealed the complex landscape that Timothy Snyder would later describe in his 2010 book as "Bloodlands".

In Western Europe, too, the reopening of archives in the early 1990s revealed new truths. France began to confront its Vichy past, while Austria - then seeking membership of the European Community - took steps in the wake of the Waldheim scandal. In 1992 (never too late, eh?) Austria agreed to compensate expelled Jews and forced labourers, followed by property restitution efforts from 2001.

What about Germany? In the 1990s, while institutional remembrance remained cautious, a grassroots movement emerged. Society itself - through associations, individuals documenting their family histories and academics - pushed to examine everything and shed light on the dark corners of the past.

In this third post in the series "What Happened to German Memory Culture?", I trace key moments in this history. Though not exhaustive, this account draws on a variety of sources and, as we approach the present, increasingly on my personal memories.

1993-1995

The Neue Wache Memorial. A one-size-fits-all memory?

Passers-by walking along Unter den Linden towards the Brandenburg Gate often overlook the Neue Wache, a magnificent example of neo-classical architecture designed by Karl Friedrich Schinke and built in 1818 to commemorate the liberation from the Napoleonic Wars.

From 1960, the restored building served as the GDR's memorial to the victims of fascism and militarism, with an eternal flame burning in its centre. In 1969, the remains of an unknown soldier and an unknown concentration camp prisoner were interred there, surrounded by soil from World War II battlefields and concentration camps.

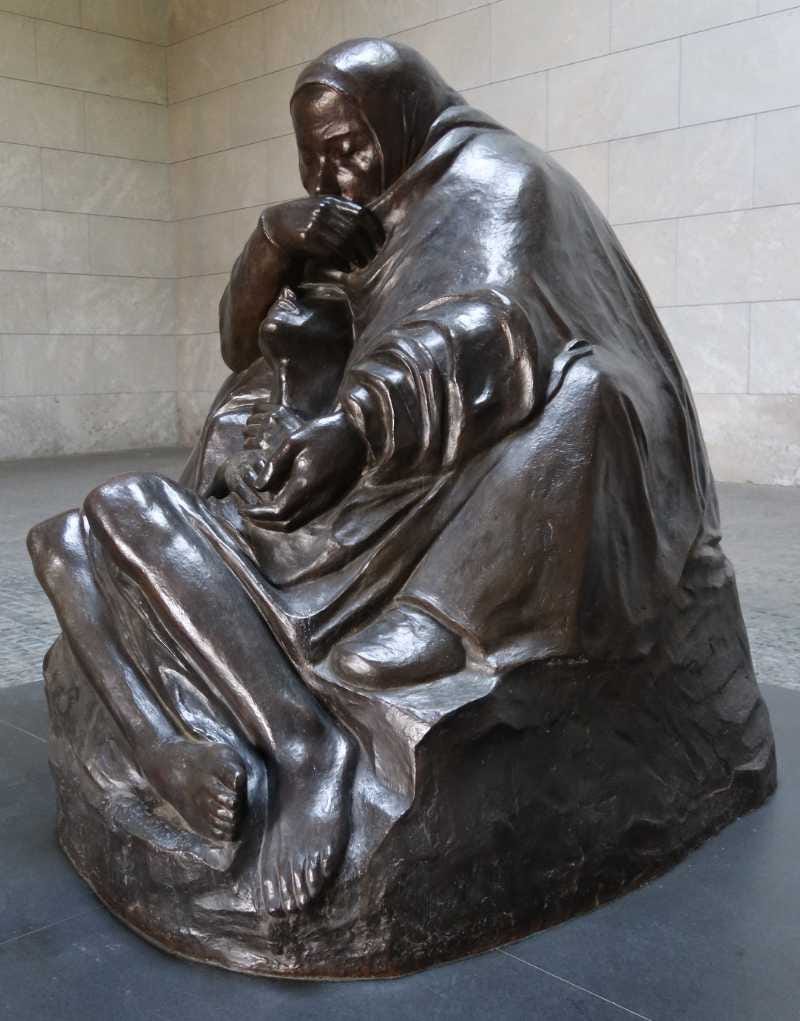

After reunification, Helmut Kohl transformed this memorial into a monument dedicated to "the victims of war and tyranny". This inscription is placed in the centre of the room, beneath a reproduction - commissioned by Kohl - of a statue by the artist Käthe Kollwitz, who had created it in honour of her son who had died in World War I. It marked the final institutional effort to forge a unified memory encompassing all eras, all wars and all the states that had succeeded one another on German soil. It was a problematic endeavour, coming at a time when the archives were opening one Pandora's box after another - revealing unacknowledged guilt, hidden complicity and crucial distinctions that needed to be made.

The result was fiercely controversial. Critics attacked the inscription as too general, seeing it as an attempt to draw a final line under historical responsibility (again, “Vergangenheitsbewältigung”, coming to terms with the past, seems to be a synonymous with the “Schlussstrich”, drawing a line).

They also took issue with Käthe Kollwitz's bronze sculpture, arguing that its pietà-like imagery made it inappropriate for commemorating non-Christian victims. At the inauguration of the memorial on a rainy November day in 1993, the voices of protesters could be heard above the rain: "Stop it!" "Nazis out!" and "German perpetrators are not victims!" Eventually, a compromise was reached: the German government agreed to install a metal plaque at the entrance listing specific groups of victims. This in turn sparked a new debate about the need for a dedicated Holocaust memorial.

Grassroots memory: actions, symbols and words that bring memory to life.

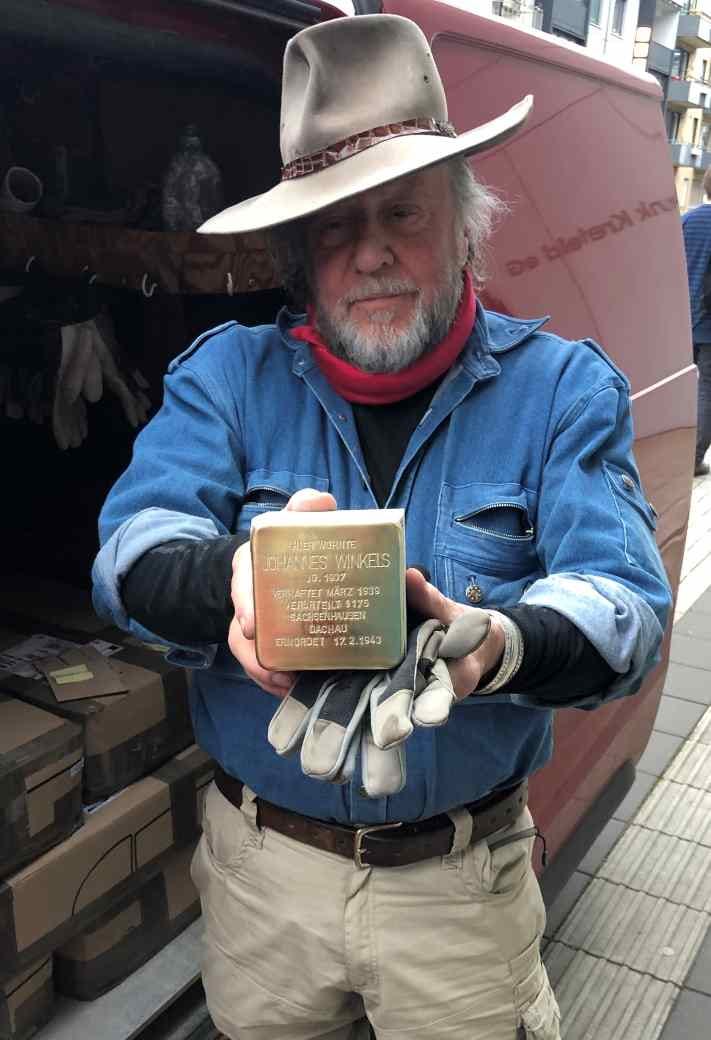

In the same year as the controversial inauguration of the Neue Wache with its overly inclusive approach, Berlin artist Gunter Demnig began conceiving what would later become known as "Stolpersteine." In March 1993, he received permission for a permanent installation in Cologne that traced the path of the first Roma and Sinti deportees from 1940 to their deportation station. The artist created this response to address the rising xenophobia in newly unified Germany.

The concept evolved—challenging cold, institutional memorials that lacked connection to victims' names and destroyed lives, Demnig and a growing group of activists developed the Stolpersteine, or stumbling stones.

Their goal was to restore names to those who had been reduced to mere numbers in concentration camps, compelling passersby to notice these names, even by chance. The first stumbling stone was laid on January 4, 1995, without municipal approval. Since then, with or without official permission—Munich, for instance, continued refusing authorization until 2015—Stolpersteine has grown to over 116,000 stones across 31 European countries, predominantly in Germany. This makes it the world's largest decentralized memorial, still coordinated by its original creator.

Following the broken silence of the late 1960s and influential mass media events like the TV series "Holocaust" in 1979, the 1990s saw the emergence of a new genre—the family novel.

This genre became remarkable both for its proliferation of titles (especially from the 2000s onward) and its growing significance among an expanding readership. These works inspired others to document their own unsettling, often deeply disturbing family histories of perpetrators. Authors used family documents, archival research, and historical scholarship to explore their personal histories while placing them within broader historical narratives. This literary trend developed alongside a growing body of German literature focused on victims and survivors of Nazism—themes that had previously appeared primarily in other languages.

Among these works, Niklas Frank's Der Vater: Eine Abrechnung, (The Father: A Revenge, 1987) was the first to capture Germany's attention. Frank examined the life of his father—who, as head of the General Government for Nazi-occupied Polish territories from 1939 to 1945, committed numerous war crimes and became known as the "Butcher of Poland," while his wife called herself the "Queen of Poland." Following his father's execution at the 1946 Nuremberg trials, Frank devoted years to researching his father's life, forcing himself to confront the enormity of these crimes. A few years later, in 1992, Ruth Klüger published her autobiographical Weiter leben. Eine Jugend (Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered). In this memoir, Klüger chronicles her Jewish childhood in Nazi-era Austria and Germany, detailing not only her survival but also her post-war struggles—particularly the profound challenge of attempting to build a normal life after such extraordinary trauma.

This literary movement continues to flourish, with compelling works by descendants of perpetrators and victims - and sometimes both - producing narratives of both historical significance and literary excellence. This literature of remembrance has become a hallmark of German literary culture1. In recent years, a third strand has emerged: stories by the children and grandchildren of German refugees - nearly 15 million people who were driven from their homes in Central Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War and sought refuge in the two German states.

1995-1999 Moving Away From the Victimhood Narrative — Confronting the Wehrmacht's Crimes.

The victimhood and denial narrative persisted well into the 1990s. The 2002 research study "Opa war kein Nazi" (Grandpa was not a Nazi) revealed that German grandchildren often romanticised or played down the role of their grandparents in National Socialism. Although some relatives were deeply involved in the Nazi system, their descendants reinterpreted them as victims, resisters or reluctant participants. This pattern is strikingly illustrated in one case where a granddaughter reimagined her grandmother - who had documented anti-Semitic views in the 1990s - as someone who had helped Jews during the war, thus fabricating a more palatable family history without any supporting evidence2.

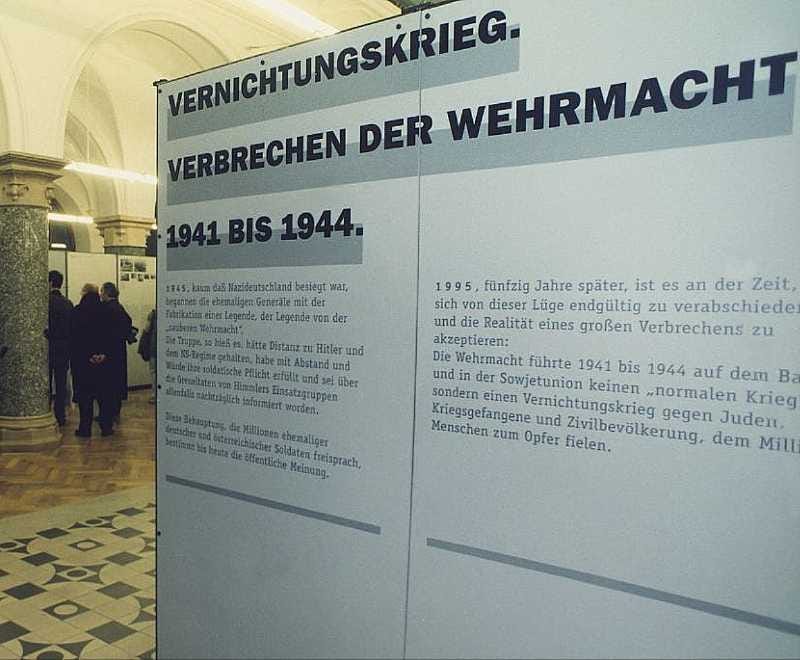

In the 1990s, however, it became difficult to turn a blind eye any longer: Germany's memory could only grow through research into the perpetrators themselves. This documentary approach culminated in a groundbreaking exhibition on the war crimes of the Wehrmacht, presented by the Hamburg Institute for Social Research in 1995 and again in 2001: "War of Extermination. Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941-1944".

The "Wehrmacht Exhibition," as it came to be known in history, opened in Hamburg on March 5, 1995, exactly thirty years ago. This exhibition struck at the most sensitive aspect of Germany's collective memory: the Wehrmacht's role in World War II. Many Germans still clung to the myth of an honorable military force distinct from a small group of Nazi fanatics.

The exhibition relied primarily on the impact of images: Large display walls showed photo series of Wehrmacht soldiers committing atrocities, including soldiers laughing in front of hanged men or conducting mass shootings. In some cases, the photos weren't from military archives but were taken privately by soldiers as souvenirs. Although historians had long known about these events, the visual evidence provoked a fresh shock among Germans—viewers couldn't help but wonder if their own fathers or grandfathers might appear in such photos. Many former Wehrmacht members felt personally defamed, saying things like »I find it very shameful that the Wehrmacht is generally blamed for this. We are seen as nest-soilers (the very German word: Nestbeschmutzer), we are making ourselves look ridiculous.«

While Hamburg remained relatively calm, the situation escalated when the exhibition reached Munich in 1997. Pro-military protests erupted there, with 5,000 neo-Nazis hanging panels declaring "German soldiers, heroes of the day!" Many dismissed it as "socialist propaganda." Left-wing counter-demonstrators confronted the right-wing groups, and the tensions culminated in an explosive attack on the exhibition rooms.

The confrontations dramatically increased public interest: nearly 900,000 people visited the exhibition, its catalogue became a bestseller, and the showing was extended through 2005, including venues across multiple countries.

However, the provocative approach led to numerous inaccuracies that academic critics quickly identified: photos had incorrect captions, historical references were missing, and at least 20 images were proven to be factually incorrect. In 2001, a revised exhibition opened in Berlin with more detailed text panels and less emphasis on shock value. Despite the controversies, this exhibition marked a crucial turning point for German society. While the 1979 "Holocaust" series had brought empathy for victims into the collective conscience—allowing people to imagine their suffering—the 1990s brought a starker realization: the perpetrators weren't just a few hundred monsters, but millions of ordinary people—fathers, mothers, grandparents.

This acknowledgment was unprecedented, especially when compared to the ongoing self-absolution of other European societies like Italy, Austria, but Poland and other Eastern European countries.

1996: Beyond the Wehrmacht Crimes—Was Germany a Nation of Willing Executioners?

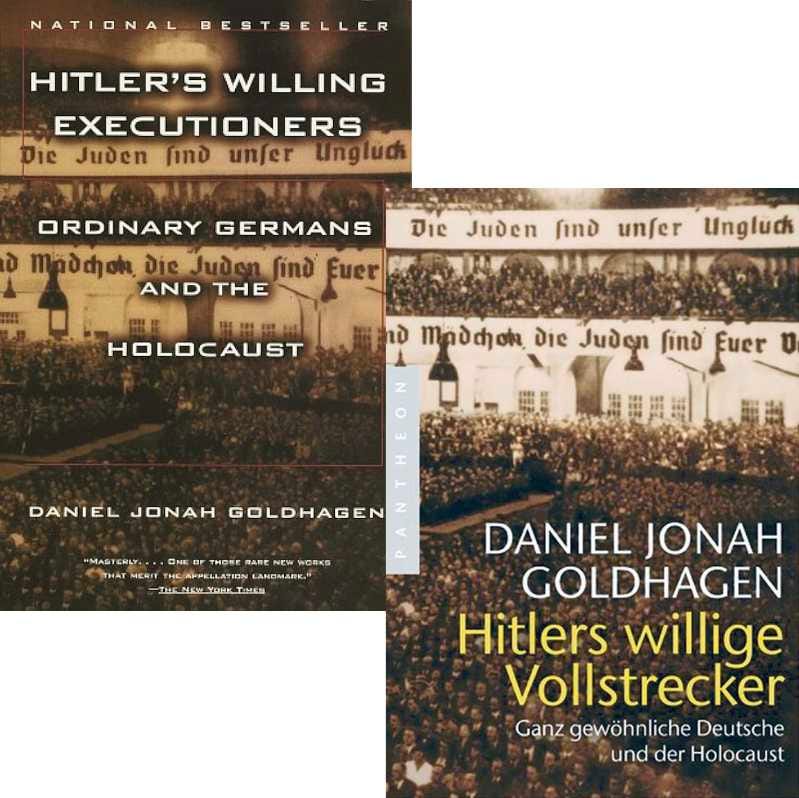

In 1996, Daniel Goldhagen's book "Hitler's Willing Executioners" (translated as "Hitler's willige Vollstrecker - Ganz gewöhnliche Deutsche und der Holocaust") sparked an intense public debate that was to have a transformative effect. The book raised a crucial question: To what extent were "ordinary" Germans responsible for the mass murder of Europe's Jews? With over 250,000 copies sold in Germany and more than a million copies sold worldwide, the book dominated major newspapers in Germany and became a central topic on prominent TV talk shows3.

In his study, Goldhagen examines what motivated Holocaust perpetrators, arguing that previous explanations were inadequate. In the foreword to the German edition, he wrote:

»I avoid ahistorical and general socio-psychological explanations - for example, that people bow to power or are prepared to do anything because of peer pressure - which are invoked reflexively as soon as the actions of the perpetrators are discussed. Instead, the perpetrators are seen here as individuals, as beings who had their convictions and were therefore also in a position to evaluate the policies of their government and to orient their decisions accordingly, decisions that they made both as individuals and as a collective.«

Goldhagen postulated that a deep-seated, "eliminationist anti-Semitism" was prevalent among ordinary Germans and the Nazi leadership alike, and served as the primary motivation for the Holocaust. He argued that this unique and deeply rooted anti-Semitism in German society had evolved over centuries, leading Germans not only to discriminate against Jews but to actively seek their extermination. This anti-Semitism, Goldhagen argued, was fundamental to German culture and served to unify the German nation by defining "the Jew" as the antithesis of "the German".

Focusing on individual actors, Goldhagen argued that common explanations such as coercion or obedience to authority failed to explain their actions. He pointed out that individuals were not punished for refusing to carry out murder orders. To support this, he examined Police Battalion 101, labour camp operations and death marches at the end of the war, noting that the guards were ordinary people with no special Nazi credentials. The cruel treatment of Jewish victims, which continued even as the war drew to a close, demonstrated a pervasive lack of empathy towards them.

The book sparked an intense debate in German society. Critics pointed out that Goldhagen's selective use of evidence and speculative interpretations undermined his credibility. His claim of a uniquely German anti-Semitism was seen as exaggerated and lacking sufficient evidence. Some also noted that other groups in Eastern Europe had shown similar or greater brutality. The criticism went beyond academic concerns - some attacked Goldhagen personally, questioning his scholarly credentials. Others made more disturbing accusations, calling him "quasi-racist" towards Germans - a particularly vicious charge given Goldhagen's Jewish-American background. The debate eventually took on anti-Semitic overtones.4 Despite criticism, Goldhagen's book made a profound impact by broadening public understanding of how ordinary Germans knowingly and willingly took part in the Holocaust.

Along with other scholarly works of the 1990s, his research helped place the Holocaust and the systematic extermination of European Jews at the center of Germany's memory culture.

This shift had far-reaching institutional consequences, leading to the development of comprehensive school curricula on the Holocaust, the establishment of memorial foundations and the organisation of commemorative events. Perhaps most importantly, it contributed to the decision to build the Holocaust Memorial in the centre of Berlin - a project that would itself spark intense debates about how Germany should remember its past and represent its national shame in the heart of its reunified capital. A debate that has not yet ended.

1998-2005 Holocaust at the center of Germany Memory Culture: can monuments dictate emotions?

The history of the Berlin Holocaust Memorial began before the fall of the Berlin Wall—in 1988, journalist Lea Rosh and her colleagues proposed building a memorial to murdered Jews in what they called "the land of the perpetrators." Their initiative came as a response to the historians' debate triggered by Ernst Nolte's 1986 article that questioned the Holocaust's uniqueness. After the Neue Wache faced criticism in 1993 for its overly generic approach to remembrance, the proposal gained momentum.

The project to create a memorial specifically for Jewish victims of the Nazi regime sparked a 17-year debate that continued until its inauguration on 10 May 2005. Every aspect drew intense scrutiny: the abstract design risked becoming meaningless over time, the scale was immense—covering 19,000 square metres with 2,711 concrete stelae—and initially, there was no historical context. This final concern was resolved during construction through the addition of an underground information centre where visitors can learn about the victims and historical sites.

In particular, the meaning and value of Holocaust remembrance was questioned: First came the concern about the centrality of the Jewish Shoah: »What about the other victims of Nazi brutality?« Roma, Bolsheviks, Marxists, Poles, those deemed "inferior", social outcasts, the mentally ill, homosexuals and other "undesirables" had also suffered. Germany's approach shifted from a single memorial for all to advocating separate monuments for each victim group. Today, while few Germans know about the memorial for the Sinti and Roma, discussions about the creation of a memorial for the Polish victims continue.

An even more radical and controversial critique came from the writer Martin Walser in his acceptance speech for the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in October 1998. In it, he challenged Germany's entire culture of remembrance centred on the Holocaust5.

The reverberations of his speech continue to this day, and are echoed in the words of prominent AfD politician Björn Höcke. Walser's crucial statements deserve to be revisited:

»I must have looked away twenty times from the worst film sequences of concentration camps. No serious person denies Auschwitz; no sane person argues about the horror of Auschwitz; but, when I am confronted with this past every day in the media, I notice that something in me resists this constant presentation of our shame. Instead of being grateful for the endless presentation of our shame, I begin to look away.«6

»That occurs to me because I am now trembling from audacity as I say: Auschwitz is not suitable for becoming a routine threat, a means of intimidation that can be used at any time, or a moral cudgel, or even a compulsory exercise. Whatever comes into being through ritualisation has the quality of lip prayer. But what suspicions are you confronted with when you say that the Germans are now a perfectly normal people, a perfectly ordinary society?«7

Finally, on the future Holocaus Memorial:

»The construction of a football pitch sized nightmare in the centre of the capital. The monumentalisation of shame. The historian Heinrich August Winkler calls this ‘negative nationalism’. I dare to assume that, even if it seems a thousand times better, it is not a bit better than its opposite. There is probably also a banality of the good.«8

When he pronounced these words, Martin Walser was accused of being a Holocaust denier. But in the months that followed, many on television, radio and in newspapers came out in support of the writer who, as one of the greatest post-war authors, enjoyed unquestioned moral authority. His words were quoted, used and then, many years later, misused.

»We Germans are the only people who have planted a monument of shame in our heart,« AfD politician Björn Höcke declared at a rally in January 2017, echoing Walser's words and adding that the time had come for a 180-degree turn in the politics of remembrance9.

After inadvertently becoming part of the rhetoric of one of AfD's most extreme representatives, Walser wrote an editorial in WELT AM SONNTAG in 2018, where he regretted his speech and self-critically described it as a "human failure." »All that remains is regret, regret, regret,« he wrote.

What also remained in the tortuous process of developing a German culture and politics of memory was the limitation of a discourse that, centred on the Holocaust of the Jews, seemed to exclude others: both the other victims and, as Germany became a multiethnic country, the new Germans who did not come from the same historical background. The 2000s were about to begin.

1995-1999: In the meantime, a new genocidal war in Europe confronts Germany with a dilemma.

What does "Nie wieder" ("Never again") truly mean? No more wars? No more genocide? And how should memory shape foreign policy?

The Srebrenica massacre occurred in 1995. It is striking how much emphasis has been placed in the last three years on the return of war to Europe with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. War had already returned to Europe more than thirty years ago with the outbreak of the Balkan conflict. This conflict forced Germany to confront a crucial dilemma in interpreting its "Never again..." mantra: never again what?

After reunification, Germany adopted a policy of restraint and strong multilateralism. While actively providing humanitarian aid and accepting refugees, it remained wary of military engagement, preferring diplomatic solutions. The dilemma of "Nie wieder..." ("never again") manifested dramatically in the Balkans—did it mean "never again war" or "never again genocide"? What would Germany choose if preventing genocide on European soil required military action? Erinnerungskultur and foreign policy are inextricably linked: Germany's processed and revised memories profoundly shaped its decisions.10

In December 1991, Germany recognized Slovenia and Croatia as independent states ahead of other European Community members. Whether this decision hastened rather than prevented the explosion of the Balkan conflict remains debatable today. When violence erupted and European, NATO, and UN forums discussed potential responses, Germany strongly resisted using military force except for defensive purposes. The prospect of "boots on the ground" was especially taboo, given Germany's historical military presence in Yugoslavia.

Until the winter of 1994, Germany limited its military involvement to three operations of a humanitarian, monitoring or purely defensive nature: Sharp Guard (1992-1996), the Sarajevo Airlift (1992-1996) and Deny Flight (1993-1996), which maintained a no-fly zone11. Building consensus for even these limited operations proved difficult: while Kohl's CDU/CSU and the SPD were already uneasy, the Greens - traditionally committed to a pacifist foreign policy - faced an existential crisis that threatened to split the party.

After Serb forces massacred thousands of Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica, Green Party whip Joschka Fischer declared that military force was justified to stop genocide.

This position would prove decisive in 1998, when the Social Democrats and Greens, after 16 years in opposition, defeated the Kohl government in elections. While NATO peacekeepers maintained a fragile peace in Bosnia, Kosovo spiraled toward conflict as ethnic Albanians sought independence from Serbia. Germany and its NATO allies attempted diplomatic negotiations, but talks failed when neither side would compromise on Kosovo's status. The Red-Green coalition now faced its gravest decision: should Germany transition from peacekeeping to warfare? Should they join in bombing Belgrade?12 When the Security Council stalled due to Russian and Chinese objections, NATO decided to launch its air campaign against Serbia without UN authorization. NATO allies accused Serbia of ethnic cleansing and argued that immediate action was necessary to save civilian lives. For SPD's Schröder and the Greens' Fischer, this presented a nightmare scenario: an allied military intervention without UN approval.

Nevertheless, the decision was made—in spring 1999, Germany joined NATO airstrikes for the first time, aiming to halt Serbian attacks on Kosovo's Albanian population. This marked the Bundeswehr's first-ever combat mission and a watershed moment in German foreign and security policy. The choice seemed clear at the time: never again genocide. Today, we face this dilemma once more, now even more tragically. "Never again"... but what exactly, in the face of Russian aggression? The intensity of German debate over these past three years, and the uncertainty ahead, is deeply rooted in historical memory.

The 2000s: what memory for Germany in the new millennium?

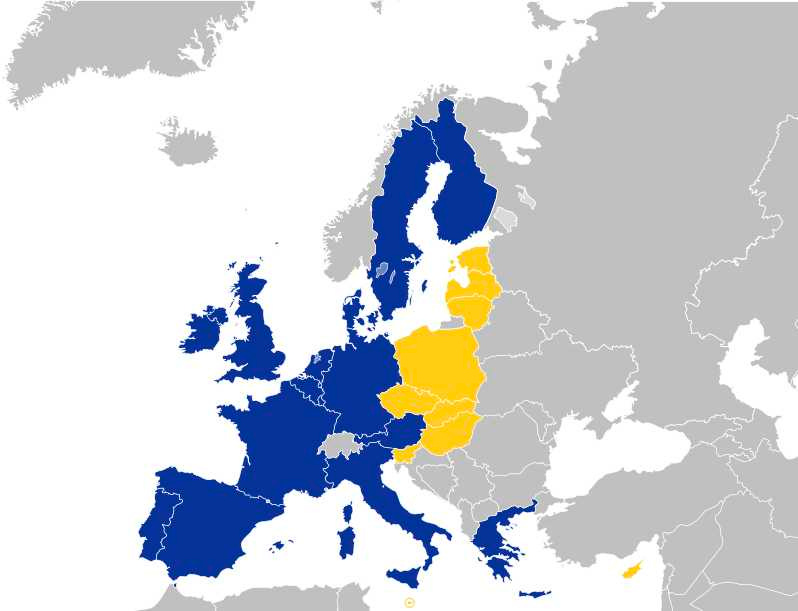

The 2000s brought both expansion and instability to the world: 2001 saw China enter the WTO, but it also marked the Twin Towers attack and the fateful decision to invade Afghanistan, followed by the 2003 Iraq War. Europe expanded as well—in 2004, ten new member states, primarily from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), joined the European Union.

These nations arrived with their own historical memories, which challenged and confronted German memory, compelling it to broaden eastward and incorporate new narratives, albeit reluctantly.

In the early 2000s, Germany was celebrated everywhere for its politics of remembrance:

»The situation is (was) paradoxical,« wrote Aleida Assmann in 2021. »For several years now, the outside world has recognised that the Germans have done something well: they have developed a culture of remembrance. The English historian Timothy Garton Ash spoke of a German DIN standard for remembrance, and in other countries there was talk of the German model«.13

However, just when it seemed that a collective memory of normative value had been consolidated, new tensions emerged: within Germany itself, but also around it, with neighbours who do not recognise themselves in the same “negative narrative”, centred on Nazism and the Holocaust, on a continent liberated in 1945, and on a claim to universalism based on the Enlightenment and human rights.

With the accession to the EU, the Western members expected the new Central and Eastern European member states to adopt the same cosmopolitan, self-critical approach to their past. They expected these nations to confront the dark sides of their history, to work towards reconciliation between victims and perpetrators, and to follow the West German experience of dealing with the past as a model.

This expectation was not fulfilled. When nationalist, right-wing parties came to power in Hungary (2010) and Poland (2015), they instead advocated a more nationalist politics of memory, emphasising their nations' 'finest moments' - especially their suffering and sacrifice.14

In the case of the Holocaust, they sought to place full responsibility on Germany: Acknowledging perpetrator status conflicted with the prevalent victim narrative and would raise Jewish property restitution claims. The nationalist right exploited these tensions, dismissing Holocaust memory as "shame pedagogy" and arguing it overshadowed other national sufferings. Poland passed laws banning any mention of Polish co-responsibility and closed relevant museums, while Hungary marginalised Holocaust remembrance, rejecting its intended role in promoting respect for minorities and human rights.

Other aspects of European memory that had previously been dominated by West German perspectives also faced challenges:

1 - The memory of the Great War. For Western Europe - especially Britain, Germany and France - it remains a trauma marked by trench warfare, carnage, the collapse of empires and the rise of nationalism. By contrast, the nations of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) see it primarily as their path to independence through the fall of Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian rule.

On remembering the Second World War:

2 - Even the question of when the war ended remains controversial. In Eastern Europe, many argue that the end of German occupation in 1945 merely gave way to Soviet occupation. For these nations, the war did not really end until they regained their independence between 1989 and 1991, and Russian troops finally withdrew from their territories in 1994.

3 - The role of the Soviet Union. While Western Europe had long seen the USSR as an ally against Hitler, CEE countries emphasised the 1939 Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact and pushed for EU recognition of Soviet responsibility for starting the Second World War. This was only achieved in September 2019 (!) with the EU Parliament's Resolution on European Remembrance, which was also motivated by Russian historical revisionism blaming Poland for WWII and the 2014 invasion of Crimea.

See also:

4 - The memory of communist crimes. The CEE countries, much more than reunified Germany, pushed for this memory to be made part of the common European consciousness alongside the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes. Germany and other Western EU countries were reluctant to do so, fearing that it would relativise and diminish the importance of Nazi crimes and Holocaust remembrance. Through successive parliamentary resolutions, the CEE countries won their battle and "totalitarian communist regimes" were formally condemned. 23 August 2009 - the day the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact was signed - became the official EU "Day of Remembrance for Victims of All Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes", which remains largely unnoticed in Germany and other Western EU countries.

5 - A continent of displaced people and refugees. The eastward enlargement of the EU has revived the long-neglected drama of the mass expulsions that took place in Europe during and after the wars of the twentieth century. Millions of people lost their homes and were forcibly relocated, often to other countries. While the remembrance of these events was of particular importance to Eastern Europeans, it also shed light on a neglected chapter of German history that has often been pushed aside in the construction of commemorative policies: more than 14 million Germans who had lived in Central and Eastern Europe before the Second World War were forced to leave their homes after 1945.

In this case, too, literature - followed by cinema and television - proved more effective than academia in stimulating public discourse, which has now found its place and even its museum: in June 2021, Berlin finally opened the Documentation Centre for Flight, Expulsion and Reconciliation (Dokumentationszentrum Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung). In the early 2000s, however, this was a controversial topic that drew harsh criticism from major newspapers - even when the author speaking out was a Nobel laureate.

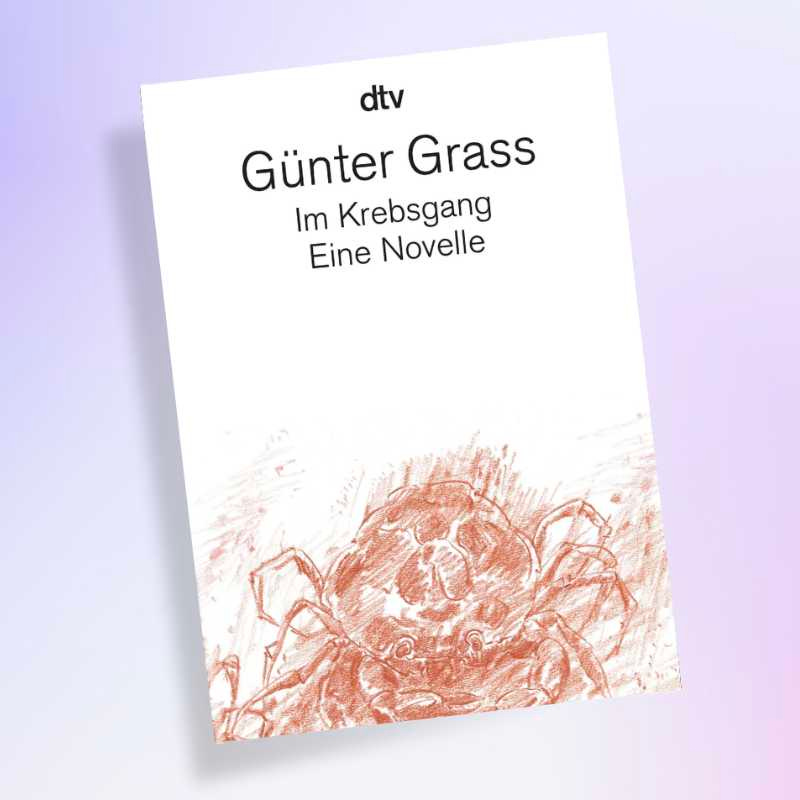

2002 Germans, too, were victims: Günther Grass.

Is it possible to acknowledge German victims of the Second World War while maintaining a balanced historical perspective, or would this inevitably push German collective memory towards right-wing interpretations?

»The madness and crimes were not only expressed in the Holocaust and did not end with the war. Of eight million German soldiers who were captured by the Russians, perhaps two million survived, and the rest were liquidated. There were 14 million refugees in Germany, half the country went directly from Nazi tyranny to communist tyranny." Of course, he didn't want to downplay the Holocaust, but it wasn't "the only crime": "We bear responsibility for the Nazi crimes, but their crimes also inflicted terrible catastrophes on the Germans, and thus they became victims.«15

The Danzig-born Nobel laureate Günther Grass said these words to the Israeli historian Tom Segev in an interview for the Haaretz newspaper in 2011. At that time, his entire body of work was under scrutiny after revealing he had joined the Waffen-SS at age 17. This disclosure temporarily overshadowed his enormous literary contribution to Vergangenheitsbewältigung (processing of the past), including his work on the suffering of German war refugees—like his own family—and civilian victims.

In 2002, his book "Im Krebsgang" (“Crabwalk”) led to a discussion about thow to deal collectively with the millions German displaced persons and civilian victims of the war.

Interwoven with a plot that reaches into his present day, when anti-Semitism and xenophobia were re-emerging and inspiring violent actions, the novella "Im Krebsgang" recounts the sinking of the German ship "Wilhelm Gustloff" on January 30th 1945, when the boat –which carried over 9,000 people– was sunk by a Soviet submarine. The "Gustloff" was one of the ships used to rescue Germans, transporting people from East Prussia to safety from the advancing Soviet army. On board were wounded marines, members of the Wehrmacht, but mostly civilians and many children. The tragedy was never recognised as a war crime, only as a mistake due to the hybrid nature of the ship - previously used as a Nazi cruise liner.

Grass questioned why Germans had long avoided discussing the suffering of expellees. Given the Holocaust and the millions of Eastern European victims of German aggression, he posed a provocative question: Could German victims be discussed, or would acknowledging German suffering be interpreted as an attempt to diminish German guilt? Grass clarified that his aim was not to relativize history, but rather to prevent right-wing revisionists from monopolizing this discourse —a position he maintained until his death in 2015.

It took further twenty years for German memory culture to process this discourse, but as we have before, we still face attempts to appropriate the memory of German victims for political gain.

2010s to today. In how many directions can memory be expanded?

The issue of expanding memory extends beyond Europe, its wars, and its displaced persons. After ignoring it for a long time, in the early 2000s Germany discovers that it is an Einwanderungsland, a country of immigration, where many new Germans arrive with memories different from the "canonized" one.

At the same time, Germany becomes a world champion in foreign trade, in academic and cultural exchanges. And the vast non-European world knocks on the doors of the old continent with a powerful question: when will you address your colonial past? German memory finds itself constrained, non-inclusive, and at times dogmatic in inspiring foreign policy.

As of the 2010s, we enter a jungle of events, debates, and positions that question everything, but do not lead yet to a new Erinnerungskultur 2.0. It is the confused period in which we still live today, where social scientist Samuel Salzborn reinterprets the entire history of German remembrance culture as "the biggest lie of the Federal Republic of Germany" (2020)16, and writer Max Czollek describes German remembrance as a "theater of Memory" (Gedächtnistheater), more about showing, less about substance (2021)17.

I will examine these past ten years by focusing on key questions, and - with particular attention to the last five years— exploring the major scandals and provocations that captured international attention.

Germany, a land of immigration: can old and new Germans share the same memory?

»And then I pin the sticker to my chest, on which a single word is written in black on white: German. That's it, this action, from then on like a confession, the writing on my chest: German. Yes, I belong, not through origin, through blonde hair, or Aryan blood, or any such nonsense, but simply through the language, and thus the culture. I go to my group and also wait silently for our guide. At the gate, above which "Arbeit macht frei" is written, all the groups line up one after the other for a bizarre photo. Only we are ashamed.«18

Navid Kermani, a German writer and orientalist born to Iranian parents, describes a profound experience while visiting Auschwitz: he had an epiphany about his German identity, feeling responsible for a history that, though not part of his ancestry, belonged to him through his connection to German culture.

If only it were so straightforward. If only all people with migration backgrounds, nowadays over 27% of Germany's population, could feel such a deep connection to the country through its culture and memory!

West Germany began admitting immigrants in 1955, first bringing in Italians, then Turks and Yugoslavs as 'guest workers' (Gastarbeiter). Their integration wasn't considered important at the time, and neither West nor East Germany addressed the issue. In fact, the 1982 coalition agreement between the CDU/CSU and FDP explicitly stated that "the Federal Republic of Germany is not an immigration country". It was only in the early 2000s that Germany acknowledged its transformation into an immigration nation - and with it the complex challenges of multiculturalism and the need to establish a guiding culture that would define German belonging through values, customs and collective memory. This fundamental question remains unresolved today.

Faced with an increasing number of people who live in here and/or are German citizens but do not share the German perpetrator experience around which German culture of remembrance is built, what does remembrance culture offer as a tool for integration?

In truth, not much - on the contrary: the institutionalized national remembrance of National Socialism's violent history risks promoting an ethnonationalist image of German society: It is not uncommon to hear nowadays that 'we in Germany', because of 'our' historical responsibility, cannot take any other position on such and such a question. It makes sense, but when expressed in these terms, it also implicitly defines the German 'we' in a way that excludes all those whose families played no part in Germany's perpetrator past. Basically, use remembrance to build a final instance of German national consciousness – a consciousness that cannot belong to non-ethnic Germans.19

Current German remembrance culture implicitly assumes that migrants lack genuine interest in or connection to the Nazi past, effectively projecting antisemitism onto these communities by suggesting "they are the antisemites now, not us!" If only it were that simple. While some immigrants may indeed be reluctant to engage with Germany's "theater of memory," many others demonstrate their commitment daily through their writings and activism. In fact, these publicists, activists, and writers sometimes find themselves reminding "bio-Germans" that the Holocaust is not exclusively a German story, but rather "just as universal as that of Cain and Abel."20

The key, explains the German-Israeli philosopher Omri Boehm, is to differentiate between guilt and responsibility: “The German people are responsible for their past, without necessarily being guilty or personally concerned. The almost absurd limit of this line of thought is the idea that even someone like me, as a German citizen, could share the responsibility of all German citizens, even though my grandparents only narrowly escaped the Holocaust and their parents did not survive it.”

2021 - Today: "Multidirectional memory" and the risk of losing one's way.

We are approaching the present: expanding memory toward Eastern Europe and reflecting on how to integrate new Germans into this memory is no longer enough.

The world outside Germany, meanwhile, has become populated with new watchwords that found their way from academia into exhibitions, public spaces, media outlets and social: postcolonialism, global south, intersectionalism. Too many new dimensions for a German memory that crystallized around the crime of all crimes, the Holocaust and made it the compass to orient both the past and the present.

2021 was a pivotal year for Germany, including for its remembrance culture, as several significant changes converged. The end of the Merkel era ushered in a new political chapter that promised reforms, including in memory policy - reforms that would later fail under the Scholz government (more on this later).

Amid controversy, the Berlin Humboldt Forum opened in the summer of 2021, reconstructed to mirror the old city palace and to house the ethnological collection - much of which consisted of treasures stolen from colonies of the same Prussian state that built the original palace, a symbol of its militarism and imperial ambitions. With almost ironic simultaneity, Germany acknowledged the genocide it committed between 1904 and 1905 against the Herero and Nama peoples in what is now Namibia. In a deal with Namibia, Germany agreed to pay 1.1 billion euros in reconstruction aid - the first real step towards reparations for its colonial crimes. A few months later, in 2022, Germany signed another agreement - this time with Nigeria, committing to return the Benin Bronzes, priceless cultural artefacts looted by the German Empire during the colonial era. After their brief display at the Humboldt Forum, these treasures made their way home in a reconciliatory gesture that seemed both belated and modest compared to Germany's monumental efforts to atone for its World War II crimes.

See also:

In 2021, Michael Rothberg's 2009 book "Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization" was translated and published in German. Rothberg argued that memories of distinct historical events—like the Holocaust and colonial traumas—are not mutually exclusive but intertwined. He proposed a framework where memories coexist and enhance collective memory rather than compete with each other. For Rothberg, this approach does not relativize the Holocaust but rather elevates it as a point of reference for decolonization movements and civil rights struggles.

While the book itself did not aim to dismantle German memory policy or create conflict between different memories, its reception in Germany sparked a fragmented discourse with multiple, sometimes provocative, positions and questions:

Inclusion of other memories: How should we deal with colonial history, other genocides and the perceived competition between different victim groups?

Line of continuity: Especially in German history: Is there a line of continuity between colonial crimes in Africa and the Holocaust? Should the conquest of Eastern Europe be seen as a colonial war, and is the genocide of the Jews a result of this colonial history?

Unique vs. comparable: An old debate resurfaces: Is the Holocaust unique and therefore incomparable, or can it be compared with other genocides? This question carried political weight in the 1980s, but now, especially after 7 October and the new Gaza war, it has become explosive.

Memory politcs or politicised memory? Is the German culture of remembrance merely a form of catechism - something formal and imposed from above - used to limit public debate and German foreign policy, especially with regard to Israel? What should be the limits of criticism of Israel?

These are important and legitimate questions. But with each new question, the political stakes have risen, along with the potential for partisan exploitation. What began as an academic debate in universities turned into a media controversy and finally into a political battleground.

In the spring of 2021, the harshest criticism of German remembrance policy — one that bordered on defamation — came from Australian-American Dirk Moses, a professor of international relations at the City College of New York, CUNY. In an article entitled "The German Catechism", published on the Swiss history blog "History of the Present" (geschichtedergegenwart.ch), Moses argued that the German interpretation of the Holocaust not only makes German elites insensitive to the suffering of other groups (read: Palestinians), but actively breeds antipathy towards them.

Moses claimed that a German "catechism" guides the actions of state officials and other elites: They invoke the uniqueness of the Holocaust as a pretext to stifle open debate about Holocaust remembrance and its implications. Instead of meaningful engagement, they mechanically perform rituals, repeat empty phrases, and cling to outdated perspectives - all while failing to acknowledge other victims of German history and contemporary human rights violations. He even set out the five commandments of this "catechism":

The Holocaust is unique because it was the unlimited Vernichtung der Juden um der Vernichtung willen (exterminating the Jews for the sake of extermination itself) distinguished from the limited and pragmatic aims of other genocides. It is the first time in history that a state had set out to destroy a people solely on ideological grounds.

It was thus a Zivilisationsbruch (civilizational rupture) and the moral foundation of the nation.

Germany has a special responsibility to Jews in Germany, and a special loyalty to Israel: “Die Sicherheit Israels ist Teil der Staatsräson unseres Landes” (Israel’s security is part of Germany’s reason of state)

Antisemitism is a distinct prejudice – and was a distinctly German one. It should not be confused with racism.

Antizionism is antisemitism.

Moses critised Germany for treating the Holocaust as a sacred trauma that must not be compared with other events at any cost, because comparison would diminish its sacred redemptive function. He argued that central to this redemptive narrative were the post-Soviet policies of accepting Soviet Jewish immigration , which were framed as restoring the "German-Jewish symbiosis", and thus allowing Germany to present itself as a moral leader. Finally, Moses accused Germans of feeling a special obligation towards Jews but not toward, say, Namibians, arguing that immigrants descended from "other" victims of the German state understandably perceive German remembrance culture as racist: in the hierarchy of suffering, some victims take precedence while others are secondary.

Why did this blog post resonate so much in Germany? The timing was ripe for criticism of German memory politics from all sides, left and right, with little concern for unintended consequences.

Less than a year before this post appeared, the historian and prominent postcolonial theorist Joseph-Achille Mbembe was invited to give a keynote speech at the Ruhrtriennale, only to be disinvited at the request of, among others, the German Federal Commissioner for Combating Anti-Semitism. Mbembe was accused of relativising the Holocaust, equating Israel with South Africa's apartheid system and questioning Israel's right to exist. Some even labelled him an anti-Semite, although he strongly denied this and was supported by Jewish scholars. This was not Germany's finest moment for freedom of speech, and it created fertile ground for Moses' theses. Then, just two weeks before the article was published, a military conflict broke out between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

On the political right, the identitarian movement - already fuelled by Covid-19 conspiracy theories - reached its tipping point. Shortly after the publication of The German Catechism, Martin Sellner, the Austrian leader of the Identitarian movement (Remember? the one who chaired the Potsdam Round Table promoting plans to forcibly relocate 20 million people out of Germany in November 2023), praised Moses's text as a 'sharp analysis'. Moses's arguments offered something for everyone: an indictment of both the German culture of guilt... and Israel.

Reading Moses' text, it becomes clear that despite the call to include other mass crimes in the German culture of remembrance, the focus is almost exclusively on Israeli politics. This instrumentalisation of historical memory serves a specific agenda: if the Holocaust becomes just one of many historical crimes, it undermines the basis for a Jewish state. Moreover, drawing parallels between the Nakba and the Holocaust casts Israel in the role of perpetrator. Indeed, not only Moses, but much of the discourse on German remembrance culture over the past five years seems to have been shaped by present-day political agendas. That's a shame. And it's dangerous.

Moreover, in examining the present - particularly the post-reunification period covered in this paper - we must acknowledge that the development of German memory policy has never sought to obscure the suffering or fate of other victims of the Germans. Rather, the problem is the opposite: the xenophobic, racist and anti-Semitic violence of the early 1990s revealed a memory that was neither properly processed nor collectively shared. What kind of catechism is this, when xenophobic and anti-Semitic words, statements, actions and attacks appear at every turn? And, as the first post in this series showed, recent years have revealed a memory that has grown dangerously thin. If this was meant to be a catechism, it has clearly failed.

See also:

A line of continuity between Colonialism and the Holocaust?

In the light of the emerging collective memory gaps, even the question of whether there is a historical line from the African "German Southwest" to "Auschwitz" becomes more of an academic exercise than a way of expanding memory. What is the point of such a discussion when many people are not even sure which territories were German colonies in Africa and what they are called today?

One fact is clear: Nazi Germany's occupation of Eastern Europe under the "General Plan East" was fundamentally a colonial war. It was characterised by settler colonies (mainly populated by ethnic Germans from the Baltic regions) and the systematic forced displacement of local populations. The German occupiers adopted a colonial language and framework in Eastern Europe, treating the local population as colonial subjects. The "Generalplan Ost" laid out a detailed strategy to enslave, resettle and deliberately starve millions of people in the occupied Soviet territories, while promoting the "Germanisation" of the region. These plans and their ruthless implementation drew heavily on a "colonial mindset" - centuries of accumulated practices for exploiting and oppressing conquered peoples.21

Yet only a small number of Nazi functionaries and Germanisation planners had personal colonial experience. Moreover, colonial thinking cannot explain the unprecedented racist radicalism of the Shoah.

It would be misleading to attribute the murder of European Jews solely to the breaking of taboos established by the genocide of the Herero and Nama. The Holocaust grew out of an ideology rather than a conflict, and aimed at total annihilation without territorial limits - even within Germany itself. Nazism differed fundamentally from all other instances of state-sponsored mass murder and violence, not in the scale of the victims or the methods of killing, but because it had no concrete enemy. The enemy was Jewish life itself - all Jewish life, the very concept of Jewish existence, was to be destroyed without exception. There was no concrete threat from Judaism: no territorial conflict, no uprisings, no violence of any kind. With no other group was the spiritual salvation of one's 'people' so inextricably linked.22

Holocaust singularity: is comparison a taboo?

A key issue is the uniqueness of the Holocaust. This deserves to be discussed, not to encourage right-wing revisionism - which has persisted throughout German post-war history - but rather to examine the legitimacy of drawing comparisons with other historical and contemporary events. We must also question Germany's tendency to reject altogether the possibility of making such comparisons. Let me begin with a recent event that has sparked international controversy.

In summer 2023, the Hannah Arendt Prize jury selected Masha Gessen for their contributions to free thought, particularly their book "The Future Is History" (2017). This pivotal work on post-Soviet Russia, which follows four Russians born during the Soviet Union's collapse, won numerous prizes including the National Book Award and Leipzig Book Fair Prize. The Hannah Arendt Prize ceremony was scheduled for December 2023 at Bremen's town hall.

However, after October 7, Gessen published an essay in The New Yorker titled "In the Shadow of the Holocaust":

There, Gessen criticized how Germany strictly controls Holocaust remembrance through laws, parliamentary resolutions (such as those against the BDS movement), and even a federal authority established to fight antisemitism—which has broad veto power over events, initiatives, and speech. Gessen described Germany's approach to Holocaust remembrance as twofold: it must be eternally remembered yet treated as unrepeatable due to its uniqueness, with this reckoning serving as a pillar of national identity. Thus, comparisons to other genocides appear threatening to the nation's foundation. Gessen's analysis extended beyond German memory: through examples from Poland, Hungary, Ukraine, and ultimately Israel, she demonstrated how Holocaust memory has become a political weapon.

Then, she addressed the sensitive issue of Gaza: Gaza has been a hyperdensely populated, impoverished, walled-in compound where only a small fraction of the population has had the right to leave for even brief periods—in other words, a ghetto. She compared this to Jewish ghettos in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe, methodically listing parallels to support the comparison.

The reaction was immediate: the Heinrich Böll Foundation (funded by the German Green Party) withdrew its support for the award, while German and international media seized on the story and asked: »Is Germany becoming a system of censorship?« Days later, partly due to the outrage of Green Party supporters, a compromise was reached: Masha Gessen was invited to a livestreamed public debate the day before the award ceremony - which took place, but not in Bremen's town hall. There, Gessen addressed the controversy over comparing Gaza to Jewish ghettos during the Nazi occupation. While acknowledging that a direct 1:1 comparison would be absurd, Gessen defended the importance of examining possible historical parallels in order to avoid civilian casualties. After all, this was in line with Hannah Arendt's philosophy.

Two crucial questions re-emerged: how " singular " is the Holocaust, and, perhaps more importantly, who has the authority to determine what comparisons are permissible in public discourse?

As for the singularity of the Holocaust, there is now a general consensus that this uniqueness is not absolute. In 1944, the Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term "genocide" not as a term specific to one historical event (not as the Shoah), but as a definition encompassing elements that had occurred and could recur, including colonial aspects such as population replacement by occupiers. This is why we can - and must - define Russia's war in Ukraine as genocidal.

The Holocaust helped to shape this definition by being examined both in its uniqueness and in aspects comparable to other events: analysing commonalities, similarities and differences using specific criteria based on common underlying elements. Thus, outside of Germany, it has never been taboo to compare the Holocaust with other events.

From a moral and historical-political perspective, the singularity thesis still makes sense in some respects: the monstrosity of the Shoah overshadowed earlier and parallel crimes in Central Europe, both in terms of murderous practice and ideological legitimation - its driving force, anti-Semitism, was not merely a variant of racism. The Nazis' unconditional drive for annihilation was unprecedented; even in 1944, when defeat was inevitable, Jews were still being deported to Auschwitz and murdered. This systematic organisation was unprecedented. Therefore, "unprecedented" rather than "singular" is the more accurate term.23

If scholars can resolve this debate rationally, if they agree that it's not an either-or (AUT-AUT) but a this-and-that (SIVE-SIVE), why does German remembrance culture resist expanding beyond the Holocaust?

The hesitation stems from several understandable concerns: fear of diluting the Holocaust's central place in memory; fear of relativising its significance; fear of losing a German identity shaped by this negative history. Collective ignorance of colonial history and its narratives also hinders this expansion.

Fear, anxiety, lack of confidence, Germany's current precarious political position and intellectual inertia have led to widespread censorship and self-censorship in recent years. It's a silencing response to rising tensions and the fear of losing control. We now find ourselves in deep confusion when we invoke the culture of memory.

The Fear of Making Mistakes: When Memory Leads to Paralysis, Silencing, and Self-censorship.

The disinvitation of Achille Mbembe in 2020 and the withdrawal of Hannah Arendt Prize sponsorship from Masha Gessen in late 2023 exemplify a broader pattern in Germany. While it's appropriate to review support for cultural institutions that openly backed Hamas terrorism after October 7, 2023 —one cannot justify using public funds to platform activists who claim Hamas has "the right to militant self-defence by all means" (as seen at the Oyoun cultural center in Neukölln, 202424)— this climate of institutional anxiety has created troubling outcomes.

These include last-minute exhibition cancellations, indefinitely postponed literary prizes (such as the 2023 Frankfurt Book Fair's LiBerature Prize, awarded but not presented to Palestinian writer Adania Shibli25), the exclusion of elected officials from ceremonies (like AFD representatives, who sit in the city senate, from the 2024 and 2025 Berlinale), and even the forced resignation of the Jewish Museum Berlin's director in 2019 over alleged BDS movement support and anti-Zionist positions26.

This growing list of concerning decisions doesn't reflect a strong state controlling artistic expression, but rather its opposite: a deep uncertainty about how German historical memory should guide present actions—particularly when that memory itself proves incomplete.

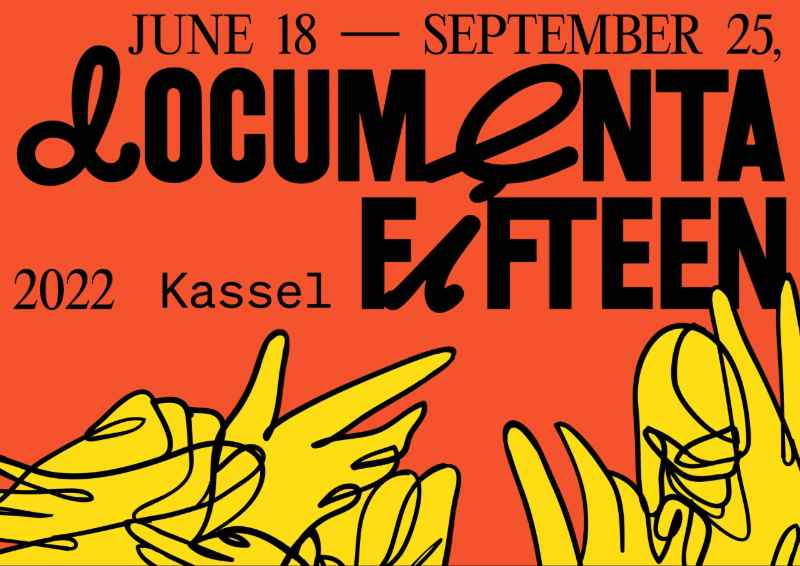

The most striking case of this ambiguity occurred at documenta in 2022. This famous art show is one of the world's most prominent exhibitions of contemporary art, taking place every five years in Kassel, Germany.

Documenta was established in 1955 in Kassel to present Germany as culturally renewed and cosmopolitan after World War II. However, the early years of documenta, particularly between 1955 and 1960, were deeply marked by the aftermath of National Socialism.

The first documenta in 1955 was organized by a team that included numerous people with Nazi backgrounds. Werner Haftmann, the intellectual head of documenta, stands as a prominent example—during the war, he worked as a partisan hunter and participated in torture and executions. Haftmann and his curator team deliberately concealed the antisemitic beliefs of artists like Emil Nolde, whose works they nevertheless displayed prominently in 1955. The exhibition served as a vehicle to reintegrate German artists and intellectuals with Nazi backgrounds into the cultural mainstream. Unsurprisingly, the early years of documenta showed a complete lack of engagement with Jewish artists or the Shoah. It functioned as a successful "washing machine."27

From this washing machine emerged one of the most significant art exhibitions, and when post-colonial discourse became fashionable in the art scene, documenta adapted once again—laundering its clothes, this time in the global south. We arrive—the exhibition takes place every five years—at 2022: documenta 15.

Here's what happened: For the first time, the prestigious German art show was led by artists from the Global South —the Indonesian collective Ruangrupa— who gathered approximately 1,500 artists and collectives in Kassel. The exhibition quickly became embroiled in controversy over antisemitism.

Even before opening, allegations emerged about Ruangrupa's connections to the BDS movement, which Germany's parliament had declared antisemitic in 2019. Soon after the opening, a major scandal erupted over Taring Padi's mural "People's Justice," which contained antisemitic imagery, including figures with Nazi-related symbols that are illegal in Germany. Despite initial resistance, the work was eventually removed.

Further controversies followed, including antisemitic imagery in an Algerian women's archive exhibition and the screening of pro-Palestinian propaganda films without context. These controversies led to several consequences: Director Sabine Schormann resigned, and the exhibition faced broad condemnation, with the Central Council of Jews in Germany declaring it "the most anti-Semitic art exhibition in the world." Der Spiegel magazine and others launched a boycott campaign against the exhibition.28

Meanwhile, some voices—including German-Israeli intellectuals—advocated for an open dialogue, proposing debates throughout the exhibition's hundred days to examine not only the 2022 antisemitism but documenta's entire history through this lens. This initiative failed.

Instead of confronting documenta's true history —one tainted by German antisemitism— it proved more expedient to target "the antisemitism of others." This approach, still maintained until recently and promoted by Germany's center-right and right-wing parties, pushes the narrative that today's antisemitism stems exclusively from outside— from the East and South (the Austrian historian Mirjam Zadoff termed this the "outsourcing" of antisemitism)29.

Today, tomorrow.

From the Holocaust emerged categories such as "crimes against humanity", human rights and the Genocide Convention as lessons of history. In 1939, Hitler could boast: "Who speaks of the Armenians today?" Today we speak not only of the Armenians and the Jews, but also of the colonised, the ethnic minorities and the indigenous peoples. We now have a transnational moral code and - although it is contested in many quarters - an International Court of Justice in The Hague. We owe this also to the way Germany has dealt with its memory.

After its slow and silent post-war start, German remembrance policy has materialised beyond memorials and Sunday speeches - when necessary, Germany has made important choices in domestic and foreign policy. It hasn't always succeeded, and the journey has been fraught with ambiguity, but we must acknowledge that the Germans are in an almost impossible position: damned if they do, damned if they don't. Consider Germany's tragic relationship with Russia and Ukraine, or the situation with Israel after 7 October: how would the world have reacted if German authorities had stood by and watched as Israel-haters distributed celebratory pastries in Berlin in response to the murderous rampage, or called for Israel's destruction?

This explains the struggle to renew and reform German remembrance policy: In February 2023, the Commissioner for Culture, Claudia Roth, proposed a new "framework concept for a culture of remembrance", integrating five areas: Nazism, the GDR dictatorship, the colonial past, democracy and immigration. The plan aimed to show how these histories are interconnected and shape modern Germany. The directors of Holocaust memorials strongly opposed the framework, warning that it could weaken the culture of remembrance by diluting the focus on the Holocaust. They feared it could lead to the relativisation of Nazi crimes. Following the criticism, Roth's office withdrew the draft for revision.

But we cannot remain inactive, unsure of how to extend memory, while we see it fading and the average German's historical awareness weakening, becoming vulnerable to fake news and malicious narratives.

In the wake of Russia's aggression against Ukraine, which exposed our ignorance of "the other side of Europe", and in the face of an increasingly distant - if not outright hostile - America, scholars such as Aleida Assmann - arguably the most important advocate of German memory as a success story, which I agree it still is - ask whether the time has come to develop a “European community of memory”30. This would help both Germany and other countries to expand their remembrance and to build the essential knowledge about ourselves and our European role in the world. Among the many national boundaries we have to overcome - banking, industry, trade barriers, etc. - national memory is also inadequate.

One Europe, one memory. Not easy, but necessary. Despite all the obstacles, Germany has already made an enormous contribution to this memory - far more than other European countries. After this long review, I haven't lost an ounce of respect for the efforts made by Germans through round tables, civil initiatives, discussions and self-criticism. I remain optimistic about the future of memory.

A non-comprehensive list of “Reckoning-with-my-family narratives”, based on titles that I know and/or have read: 1987 Niklas Frank – Der Vater: Eine Abrechnung • 1999 Hans-Ulrich Treichel – Der Verlorene • 2003 Uwe Timm – Am Beispiel meines Bruders • 2004 Viola Roggenkamp – Familienleben • 2004 Dagmar Leupold – Nach den Kriegen • 2004 Wibke Bruhns – Meines Vaters Land • 2005 Katrin Himmler – Die Brüder Himmler • 2008 Alexandra Senfft – Schweigen tut weh • 2014 Katja Petrowskaja – Vielleicht Esther • 2015 Anne Weber – Ahnen. Ein Zeitreisetagebuch • 2015 Per Leo – Flut und Boden • 2016 Alexandra Senfft – Der lange Schatten der Täter. Nachkommen stellen sich ihrer NS-Familiengeschichte • 2018 Geraldine Schwarz – Die Gedächtnislosen • 2022 Sacha Batthyány – Und was hat das mit mir zu tun? Ein Verbrechen im März 1945. Die Geschichte meiner Familie • 2022 Veronica Frenzel – In eurem Schatten beginnt mein Tag: Wie die Nazi-Vergangenheit meiner Familie mich bis heute rassistisch prägt. To these, I'll add a superb graphic novel written in English by German-American Norah Krug, Heimat, an international bestseller published in 2020.

In their study "Grandpa Was Not a Nazi" (Grandpa Was Not a Nazi), social psychologist Harald Welzer, social researcher Sabine Moller, and psychologist Karoline Tschuggnall investigated family memories of the Nazi era by interviewing 40 families and 142 individuals across three generations. Although the descendants had learned extensively about Nazi atrocities in school, they—including the third generation—uniformly denied that their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents could have been perpetrators. The respondents instead consistently portrayed their ancestors as victims of the war, with some even claiming their relatives had helped Nazi victims.

Zukunft braucht Erinnerung: „Hitlers willige Vollstrecker“ und die Goldhagen-Debatte in Deutschland, (‘Hitler's willing executioners’ and the Goldhagen debate in Germany) 2008

Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Die "Goldhagen-Debatte" : ein Historikerstreit in der Mediengesellschaft, (The ‘Goldhagen Debate’: a historian's dispute in the media society) 1997

About the 1998 Martin Walser speech and the related debate: Official site of the Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels (Peace Prize of the German Book Trade); 1998: The Walser-Bubis controversy, 2013, Jüdische Allgemeine (in German); Populism did not start on the street, September 24, 2018, Die Zeit; "Moral club Auschwitz" - Martin Walser's controversial Peace Prize speech, 11.10.1998, SWR2 Archivradio

»Von den schlimmsten Filmsequenzen aus Konzentrationslagern habe ich bestimmt schon zwanzigmal weggeschaut. Kein ernstzunehmender Mensch leugnet Auschwitz; kein noch zurechnungsfähiger Mensch deutelt an der Grauenhaftigkeit von Auschwitz herum; wenn mir aber jeden Tag in den Medien diese Vergangenheit vorgehalten wird, merke ich, daß sich in mir etwas gegen diese Dauerpräsentation unserer Schande wehrt. Anstatt dankbar zu sein für die unaufhörliche Präsentation unserer Schande, fange ich an wegzuschauen.« (Complete original text here, October 11, 1998)

»Das fällt mir ein, weil ich jetzt wieder vor Kühnheit zittere, wenn ich sage: Auschwitz eignet sich nicht, dafür Drohroutine zu werden, jederzeit einsetzbares Einschüchterungsmittel oder Moralkeule oder auch nur Pflichtübung. Was durch Ritualisierung zustande kommt, ist von der Qualität des Lippengebets. Aber in welchen Verdacht gerät man, wenn man sagt, die Deutschen seien jetzt ein ganz normales Volk, eine ganz gewöhnliche Gesellschaft?« (Complete original text here, October 11, 1998)

»Die Betonierung des Zentrums der Hauptstadt mit einem fußballfeldgroßen Alptraum. Die Monumentalisierung der Schande. Der Historiker Heinrich August Winkler nennt das "negativen Nationalismus". Daß der, auch wenn er sich tausendmal besser vorkommt, kein bißchen besser ist als sein Gegenteil, wage ich zu vermuten. Wahrscheinlich gibt es auch eine Banalität des Guten.« (Complete original text here, October 11, 1998)

Herr Höcke und das Holocaustmahnmal (Mr Höcke and the Holocaust memorial), January 24, 2017 - die Zeit.

Andrew Port, Never Again: Germans and Genocide after the Holocaust (2023)

Bundeswehr.de: Abgeschlossene Einsätze und anerkannte Missionen der Bundeswehr (Completed operations and recognised missions of the Bundeswehr)

Deusche Welle, December 28, 2010, The Balkan decision

Assmann, Aleida: Das neue Unbehagen an der Erinnerungskultur. (The new unease about the culture of remembrance), 2021

Törnquist-Plewa, B. (2024). After All These Years, Still Divided by Memories? East Central Europe and EU Politics of Memory Twenty Years after the Enlargement. East European Politics and Societies, 38(4), 1080-1092. https://doi.org/10.1177/08883254241295464

»Der Wahnsinn und die Verbrechen fanden nicht nur ihren Ausdruck im Holocaust und endeten nicht mit dem Kriegsende. Von acht Millionen deutschen Soldaten, die von den Russen gefangen genommen wurden, haben vielleicht zwei Millionen überlebt, und der Rest wurde liquidiert. Es gab 14 Millionen Flüchtlinge in Deutschland, die Hälfte des Landes wechselte direkt von der Nazityrannei in die kommunistische Tyrannei.“ Natürlich wolle er den Holocaust nicht verharmlosen, aber das sei nicht „das einzige Verbrechen“ gewesen: „Wir tragen die Verantwortung für die Verbrechen der Nazis, aber ihre Verbrechen fügten auch den Deutschen schlimme Katastrophen zu, und so wurden sie zu Opfern«

Salzborn, Samuel: Kollektive Unschuld (Collective Innocence. The self-rejection of the Shoah in German memory. As far of my knowledge, only available in German) Hentrich & Hentrich, 2020 • One of the strongest (excessive?) critiques of German Remembrance Culture which highlights longstanding mechanisms of denial and the inversion of perpetrator-victim narratives.

Czollek, Max: Desintegriert euch! (Dis-similate!), Hanser Verlag, 2018 • A powerful critique of how Germany integrates minorities into its narrative. Czollek's thesis: German memory culture is a "theatre of memory" that forces minorities to conform to the dominant culture's expectations in order to maintain an unrealistic image of unity. His solution: reject integration and embrace authentic identities, even if they conflict.

»Und dann hefte ich den Aufkleber an die Brust, auf dem schwarz auf weiß ein einziges Wort steht: deutsch. Das ist es, diese Handlung, von da an wie ein Geständnis der Schriftzug auf meiner Brust: deutsch. Ja, ich gehöre dazu, nicht durch die Herkunft, durch blonde Haare, arisches Blut oder so einen Mist, sondern schlicht durch die Sprache, damit die Kultur. Ich gehe zu meiner Gruppe und warte ebenfalls stumm auf unsere Führerin. Im Tor, über dem «Arbeit macht frei» steht, stellen sich nacheinander alle Gruppen zu einem bizarren Photo auf. Nur wir schämen uns.« Navid Kermani in Entlang den Gräben (Along the Trenches: A Journey through Eastern Europe to Isfahan) 2018.

“The future of remembering” A conversation among Omri Boehm, Teresa Koloma Beck, Carola Lentz via Eurozine, February 19, 2025

Meron Mendel: Über Israel reden. Eine deutsche Debatte (Talking about Israel. A German Debate), 2023

O'Sullivan, Rachel: Nazi Germany, Annexed Poland and Colonial Rule. Resettlement, Germanization and Population Policies in Comparative Perspective, 2023.

Klävers, Steffen: Decolonizing Auschwitz? Komparativ-postkoloniale Ansätze in der Holocaustforschung (Decolonising Auschwitz? Comparative-postcolonial approaches in Holocaust research), 2019

Sznaider, Nathan: Fluchtpunkte der Erinnerung. Über die Gegenwart von Holocaust und Kolonialismus (Holocaust and Colonialism: Vanishing Points of Remembrance), 2022

August 14, 2024: Oyoun has to leave cultural centre - Senate puts location out to tender again, RBB (in German, free to read)

October 19, 2023: LiBeraturpreis to Adania Shibli: accusations against Litprom, Deutsche Welle (in German, free to read)

June 15, 2019: Peter Schäfer leaves after criticism: Director of the Jewish Museum Berlin resigns, Tagesspiegel (in German, free to read)

June 26, 2022: The old Nazis wouldn't have dared to do that, Das hätten sich die Alt-Nazis nicht getraut, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, (in German, free to read)

2023 "A dark red line has been crossed" - Research and Information Center on Anti-Semitism Hessen at the Democracy Center Hessen (PDF in German)

Zadoff, Mirjam: "Gewalt und Gedächtnis: Globale Erinnerung im 21. Jahrhundert", 2023).

Assmann, Aleida: Der europäische Traum. Vier Lehren aus der Geschichte, (The European dream. Four lessons from history), 2018

Share this post