Berlin is a city where the past refuses to stay buried. While many passersby might be impressed by its shining post-modern architecture, here every cobblestone whispers of empires and revolutions, violence and wars, of people coming to thrive and others deported. Even the newest buildings are haunted by ghosts of what came before. This is Berlin, and at its heart stands a palace… a controversial palace.

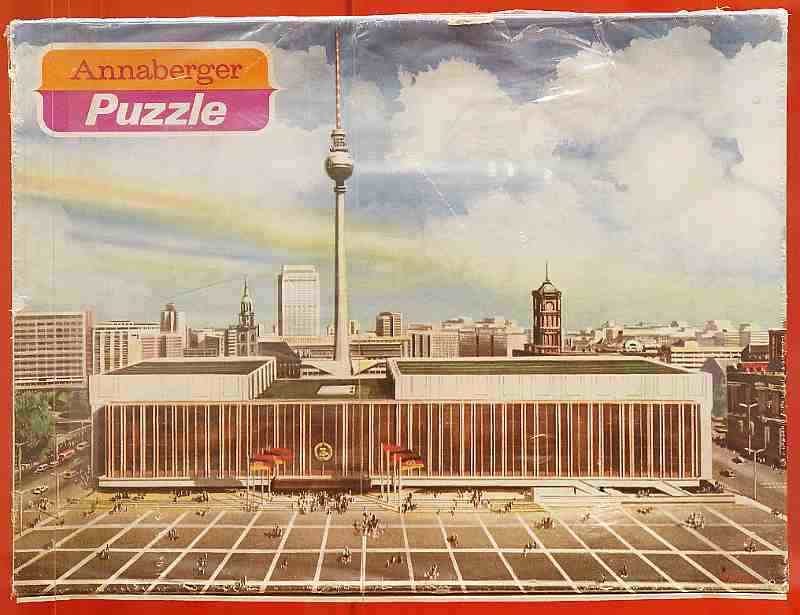

The Humboldt Forum. Gleaming and new, it stands like an opulent jewel box on Museum Island. But this is no ordinary museum complex. It's a resurrection — a deliberate echo of Prussia's imperial splendor — built on the very spot where the East German Palace of the Republic, the Palast der Republik, once proudly stood.

This is a tale of demolition and reconstruction, of colliding memories and political maneuvering. It's about Germany grappling with its past — all of its pasts. It exposes the limitations of its much-lauded Erinnerungskultur, the German culture of remembrance. It's about a nation still striving to define itself: from colonialism to communism, from genocide to gentrification, from divided to reunited.

The Humboldt Forum has become yet another flashpoint in an endless debate: the omnipresent, daily, almost obsessive East-West German divide. It's still here, 35 years after the fall of the Wall, and more heated than ever.

Modern meets baroque, new intertwines with old.

As you approach the centre of Berlin from the east, taking the classic route through Berlin - crossing Unter den Linden, passing under the iconic Brandenburg Gate and heading towards the Tiergarten and the sprawling government complex - there it is: the Humboldt Forum, your first stop on this journey through German history. Its eastern façade is all modern minimalism, a surreal backdrop straight out of a De Chirico painting.

But as you walk along its side, the neo-baroque section comes into view - its yellowish hue and twin portals leading to courtyards. It's grand, yet somehow intimidating.

This mix of architectural styles reflects a trend in Berlin and Brandenburg, like the neo-baroque revival in Potsdam's centre a decade ago. We've got used to it, but it still feels a bit artificial - like something between Disneyland and Las Vegas.

And yet, Berlin just rolls with it. This city has seen it all—from the grandeur of Prussian palaces to the stark functionality of communist architecture. After thirty years of chaotic yet deliberate urban development, the city has become a patchwork of styles. We've learned to embrace the whole spectrum: from the grand and sleek to the gritty and awkward; from Nazi-era public buildings, stadiums, and airports to Bauhaus public housing; from the futuristic curves of the Shell House to the peculiar Kottbusser Tor in West Berlin; from the refurbished Wohnkasernen of Prenzlauer Berg to the East's Plattenbauten. Now, into this mix comes the Humboldt Forum, and honestly, it's a whole new level of "What were they thinking when they built it?"

Architectural drama in three acts.

The complex is named after the famous explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. As its name suggests, the Forum aims to be a real meeting place, a space for dialogue and where ethnographic collections and ideas about a global future come together.

After three years of operation, the Humboldt Forum faces its most challenging debate yet. The spotlight shines on its predecessors—an exhibition exploring the legacy of the Palace of the Republic (Palast der Republik), the GDR symbol it replaced, and its precursor, the Berlin Imperial Palace (Berliner Stadtschloß). Built on the foundations of colonialism, slavery, and plunder, the older Berliner Schloß stands in stark contrast to the GDR's socialist vision. Can the Humboldt Forum truly bridge the historical divide it has inherited and supplanted?

For Berliners over fifty, it's complicated. Architecture isn't just about politics - it's deeply emotional. And that's what the current exhibition, Blown Away (Hin und Weg), taps into: the political and sentimental attachments people have to the Palast der Republik. The memories associated with it. The building that stood here before the shiny new Forum took its place.

At the entrance, there's a simple but revealing survey. Visitors are asked whether the Palace of the Republic should have been demolished to make way for the Humboldt Forum. They vote with paper discs, and as the piles grow, the message becomes clear.

The winner is still the old GDR Palace of the Republic. Even some young people, who may not even remember sitting in one of its popular restaurants or listening to its concerts, vote for the old modernist communist building over the new baroque palace-inspired forum. To understand this architectural drama, this clash of emotions and nostalgia that goes deeper than just a longing for the past and speaks to the politics of the present, we need to rewind the tape and go back to the beginning.

Demolition after demolition

This is a story of one demolition after another. Where the Humboldt Forum now stands, there was another palace from 1443 to 1918 - the official residence of the powerful Hohenzollern dynasty. This palace, built in the 15th century, was also a symbol of unification, but on a smaller scale - Berlin itself was created by the merger of two cities, Berlin and Cölln, in the same way that Buda and Pest came together on the Danube to form Budapest.

Over the centuries, the palace evolved with the times and Prussia's growing wealth. In the 16th century it took on a Renaissance look. Then, in 1701, when Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg, crowned himself King Frederick I of Prussia, the palace was upgraded - it entered the Baroque era. It's this version of the palace that the reconstruction of the Humboldt Forum is trying to recreate today.

But it's not just about the architecture. This palace has witnessed some of the most dramatic moments in German history. It was here, in the square in front of the palace, that the March Revolution of 1848 erupted - a violent uprising that was part of a wider wave of revolutions across Europe and was brutally crushed on the palace steps. All sorts of events took place both outside and inside the palace. Colonial subjects paraded through its doors, treasures looted from those colonies were piled inside.

Fast forward to the 9th of November 1918. The German monarchy had collapsed. As Philipp Scheidemann stood outside the Reichstag proclaiming the German Republic, the revolutionary socialist Karl Liebknecht stormed into the palace. No one stopped him. He leaned out of a large window and made his own proclamation - this one for a 'Free Socialist Republic of Germany', with a powerful speech that's now part of history.

«Party comrades, ... the day of freedom has dawned. Never again will a Hohenzollern set foot on this square. … Today an immense crowd of enthusiastic proletarians stands in the same place to pay homage to the new freedom. … I proclaim the Free Socialist Republic of Germany… where there will be no more servants, and every honest worker will find the honest reward for his labor.'»

Liebknecht's proclamation marked the beginning of a chaotic and violent chapter in German history - the civil war that followed, the birth of the Weimar Republic, and not far from this very palace, Liebknecht himself was murdered, along with Rosa Luxemburg, by fascist militias.

Fast forward again - this time to February 1945. The palace had been bombed and burned, and by the end of the war, like much of central Berlin, it lay in ruins. What remained of the palace was a ghostly shell, a reminder of a past that Germany's new democratic republic, born in 1949, wanted to leave behind.

And how did they plan to proceed? With demolition, of course. In 1950, the remains of the palace were demolished, the rubble taken away and some of it used to rebuild houses. And the huge empty space left behind? It became the stage for huge socialist rallies, a blank canvas for a new vision of Germany.

A new palace: for State and People

As the DDR gained more international recognition, so did the idea of building something that would symbolize its newfound legitimacy. In 1958, they launched an ideas competition for the 'socialist redesign' of Berlin's city center. Some things took off quickly — like the famous TV tower, known as 'Alex,' which has dominated Berlin's skyline since 1969 and still holds the title of Germany’s tallest building.

But when it came to replacing the old castle with a new socialist structure, things moved a bit slower. This delay was partly because the leaders couldn’t agree on what the building should be. Walter Ulbricht had imagined a 'House of the State,' while Erich Honecker pushed for a 'House of the People.'

Eventually, they found a compromise. Honecker’s vision was a place where, and I quote, “the People’s Chamber would meet responsibly,” but also where “our culture would find a home, along with the cheerfulness and sociability of the working people.” The foundation stone was finally laid on November 2, 1973.

Less than three years later, in 1976, the Palace opened its doors. Not an ordinary building: It was huge, with an enormous two-story foyer at its heart — 86 meters long and 42 meters wide — connecting the more formal, institutional side of things with the public spaces. It even doubled as an art gallery.

Anyone who walked through that foyer, whether a local or an international visitor, would tell you it was something special. The space felt open, modern, futuristic. It wasn’t the kind of drab, brutalist architecture we often associate with socialist regimes. This was innovative, clean, and even elegant.

It was also a great PR move. By 1973, the GDR had been admitted to the United Nations alongside West Germany, and the Palace was a way to show the world they were a serious player on the global stage.

But there was a price — a hefty one. The construction costs soared to around 750 million GDR marks, making it the most expensive project in the country’s history. Adjusted for inflation and converted into today’s money, that would be well over a billion euros — a mind-boggling sum, even for today’s Berlin.

Of course, the citizens of the GDR had their own thoughts about all this extravagance. In typical East German fashion, they used humor to cope. The Palace was nicknamed the 'Ballast of the Republic,' and because of its lavish lighting, it was also called 'Erich Honecker’s Lamp Shop.' Fun fact: those iconic modernist lamps were so sought after that when the Palace was dismantled, they sold them off at auctions to collectors.

A Palace pulsing with life

Aesthetics matter, sure, but experience? That’s what really sticks with you. And that’s exactly what the Palace of the Republic delivered. Despite the jokes and the constant suspicion of Stasi surveillance, it became a magnet for crowds.

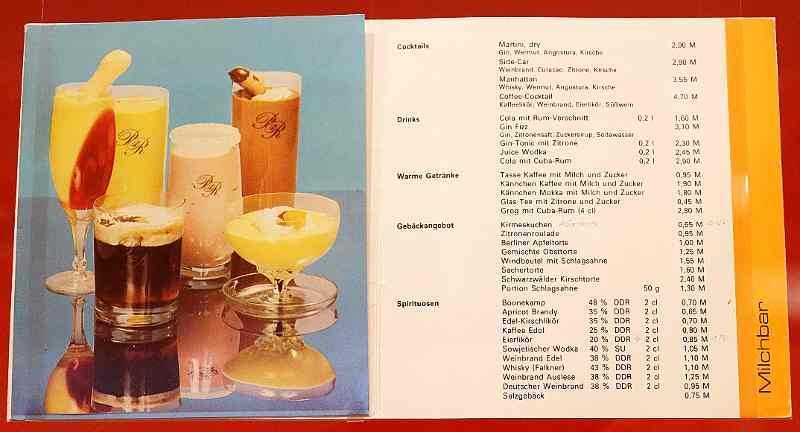

Between 1976 and 1990, over 60 million people walked through its doors. Concerts, theater, a meal at one of the 13 restaurants, cafés, or bars—or even just chilling out in that massive foyer—the Palace was the place to be.

Open every day from 10 a.m. to midnight, it offered dining options that, by DDR standards, were pretty impressive. Some say the food selection could easily rival Berlin's modern food courts today—especially when you think about the value for money. There were dishes you just couldn’t find anywhere else in East Germany.

The cultural program wasn’t just about communist anthems and state propaganda. You had everything: folklore nights, rock concerts, theater productions, symphony performances. There was even a TV studio where live tapings of popular variety shows happened. It was entertainment central. The Palace had a bowling alley too, and it was a hit.

Then there was the 'Great Hall,' which was a technical marvel for its time. It could transform at the drop of a hat—one minute, it’s set up for a massive concert, the next, it’s hosting a political assembly, or it could even be broken down into smaller spaces for more intimate events.

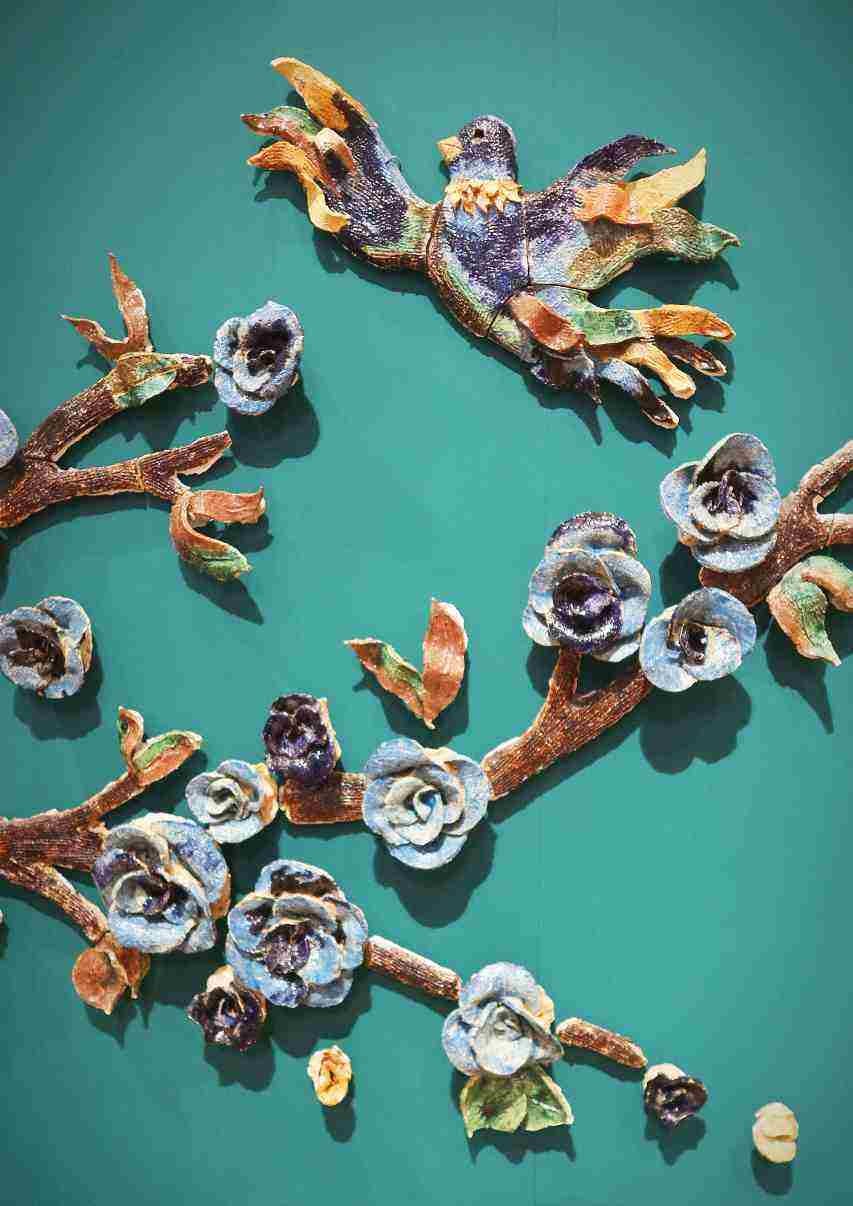

The Palace wasn’t just a building—it was the state’s way of showing that the 'workers’ and peasants’ state' could offer more than just hard labor and rationed goods. It was about elevating the people through arts and culture. Inside, there were over 300 pieces of art by more than 100 East German artists. Sure, a lot of it had political messaging — approved by the state, of course — but it was quality art. By the '70s, you could see the East opening up a bit in its cultural policy. The themes weren’t just about class struggle or the glorious future of socialism anymore. You’d see abstract pieces, flowers, landscapes — it was a shift, subtle but noticeable.

And people loved it. They made memories there — family outings, first dates, concerts with friends. It wasn’t all doom and gloom like we see in movies like The Lives of Others. For many, the Palace held some of the best moments of their lives. So when they started tearing it down, it wasn’t just a building that was disappearing. It was a part of their history, their personal stories. Imagine a place where you grew up, hung out with loved ones, maybe even performed on stage—just... gone. No wonder people felt a real sense of loss as the walls came down.

The Eighties

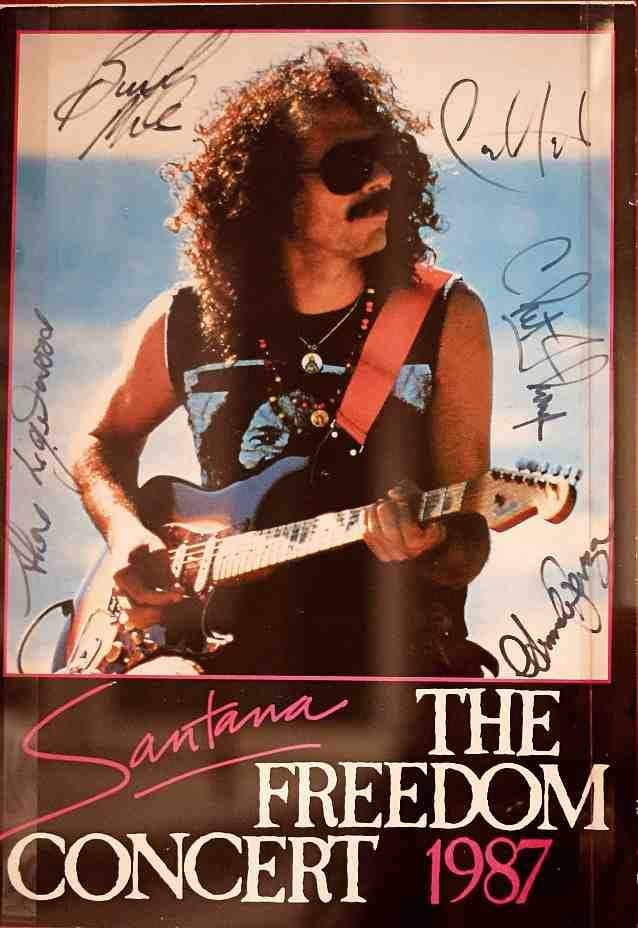

Welcome to the '80s! For us Western teenagers, music was our lifeblood. Looking back, we can proudly say we witnessed some of pop music's finest moments. Disco, electronic, punk, metal — all the musical innovations that took root in the '70s flourished spectacularly in the '80s. And: our friends behind the Iron Curtain weren't entirely left out. Despite the division, they grooved to many of the same tunes. When it came to culture, the GDR was worlds apart from North Korea.

The regime knew it couldn’t ignore the power of popular music, and the Palast der Republik became a key venue. The list of legendary concerts held there is wild: from Santana to Miriam Makeba, from German pop stars like Udo Lindenberg and Udo Jürgens, to punk bands and reggae artists. These performances left unforgettable memories for those who were there—and even for those of us watching from afar.

And as we edge closer to 1989, one memory at a time, the Palast der Republik becomes the epicenter of the events that ultimately brought down the Berlin Wall.

The Palace was this strange hybrid — a place for the people, but also a showcase for the state. It was home to the DDR parliament, the Volkskammer, which held its plenary sessions up to four times a year. But it was also a grand stage for state events with international dignitaries. In many ways, the Palace was the GDR’s shiny business card — though, by then, the regime was heading straight for default.

Fast forward to October 7, 1989 — the DDR’s 40th anniversary. The leadership threw a big celebration, complete with parades and tanks rolling down Karl-Marx-Allee. After that, they all headed to the Palast der Republik for a State Dinner.

The mood was celebratory, to say the least. State guests like Yasser Arafat, Nicolae Ceaușescu, and Mikhail Gorbachev joined Erich Honecker in singing the ‘Internationale,’ the anthem of the socialist movement. But outside, about 3,000 people had gathered, chanting ‘Gorbi, help us!’ They were loud enough to be heard inside the dinner hall.

It didn’t go unnoticed. Gorbachev and his wife, Raisa, looked visibly uneasy, and the Soviet leader kept glancing at his watch, counting down the minutes until he could leave for Moscow.

When Gorbachev finally slipped out through a back exit, the order came down for the Stasi and Volkspolizei to break up the demonstration. They pushed the crowd from Alexanderplatz toward Prenzlauer Berg, where the Gethsemane Church had become a rallying point for young people praying and chanting for freedom. And there, Stasi units brutally attacked the peaceful demonstrators—beating anyone in sight, especially women, in an effort to send a message.

In that moment, the Palast der Republik entered the global spotlight as the backdrop of state violence in October 1989. Less than a year later, on August 23, 1990, the newly elected Volkskammer—the first and last democratically elected in the GDR—met to vote on East Germany’s accession to West Germany. It was a pivotal day. After a tense session, 294 members of parliament voted in favor, 62 against, and seven abstained. This was the moment that sealed the fate of East Germany.

For many, these memories alone were enough to argue for keeping the Palast der Republik standing. And it’s hard to argue with that.

The Palast der Republik: Preserve or Demolish?

With the fall of the DDR and reunification, the floodgates opened—archives were unsealed, and secrets came spilling out. And some of those secrets were tied directly to the Palace of the Republic. It was an incredible piece of architecture, no doubt—innovative, full of life. But it was also a building that quite literally harbored death.

To ensure fire protection, all the steel beams were coated with sprayed asbestos — imported straight from England. Experts had already warned about the dangers of this carcinogenic mineral back in the '60s. But in the ‘70s, asbestos was still considered this 'miracle fiber.' And not just in the DDR — plenty of countries in the West were still using it well into the ‘80s. East Germany actually outlawed asbestos in 1969, ahead of its time. Yet, they made a special exception for the Palace of the Republic.

Years after the Palace had opened its doors, something sinister was happening: asbestos was quietly trickling down from the false ceiling of the 'Great Hall' onto the audience during concerts in the '80s. The regime classified it as a state secret. It wasn’t until September 19, 1990 — just two weeks before reunification — that the People’s Chamber ordered the closure of its own venue, anticipating stricter German safety standards. The Palace of the Republic was shut down for good and never reopened.

From that point on, it just sat there. Unused, unmaintained. It became a 'lost place,' a monumental ghost right in the heart of Berlin.

But then, in November 1998, things started to change. Renovations began, first to remove all the asbestos and other contaminated materials. And there was a bit of hope for the Palace’s future. Local culture-makers struck a deal to temporarily use the space for concerts, theater performances, and exhibitions in the early 2000s. I was lucky enough to be there in September 2004 for a dance and video art performance by the world-famous Sasha Waltz & Guests. It was surreal. The building had been stripped down to its skeleton, almost bare, but the light streaming in from the huge windowed façade was both powerful and gentle. Just a few weeks later, on September 30, 2004, Rammstein — Germany’s most famous hard rock band—tore up the stage in that same space. One year later, Frank Castorf, probably the most important theater director of our times, famous for his XXL and extremely long productions, staged a grand adaptation of Alfred Döblin's famous 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz.

In 2004 and 2005, the Palace hosted nearly 1,000 events, drawing over half a million visitors. It was still making history — cultural history. Berlin had seemingly embraced this enormous skeleton of a building; it fit perfectly into the city's vibrant, rebellious spirit. Some even envisioned its deep renovation, perhaps integrating it with a flashy new design by the same star architects who had reshaped Potsdamer Platz. However, by this time, the debate over the Palace's fate had become a political minefield—and the argument was only growing more intense.

A short-lived debate (but the aftermath is still here)

The debate wasn’t really about architecture or what Berlin’s cultural and societal needs were. Instead, it turned into this full-blown ideological clash — left vs. right, East vs. West. In a way, it was a precursor to the heated East-West debates we’ve been seeing over the past five years.

There were a lot of people fighting to save the Palace of the Republic. Take Helmut Engel, for example—one of Germany’s top art historians. He was born in the West but had moved to Berlin and worked as the city’s art conservator for several years. In 1992, he came out and said,

We should list the Palace as a historical monument.

Sounds reasonable, right? Not to everyone. The political backlash was immediate—the German Liberal Party even called for his resignation. That same year, another group popped up—the Förderverein Berliner Schloss. Their mission? Rebuild the Royal Palace. They raised a ton of money and lobbied hard to make it happen.

Then, in 1993, Berlin’s government made its decision: the Palace of the Republic was going to be demolished and replaced. But it wasn’t like the wrecking ball showed up the next day. They knew it would take years to clear out the asbestos, so there was time—at least a decade—to figure out what would go up in its place. In the meantime, they used the Palace for events, letting people pitch ideas for the future.

But this whole thing didn’t happen in a vacuum. While the pro-castle group got louder, especially in Bonn where the Bundestag was still based, something interesting was happening globally. The architectural world was rediscovering and celebrating East German modernism. The Palace of the Republic became this shining example, right up there with the Conference Palace in Dresden, which is still standing tall today.

Fast forward to 2003, and the German Bundestag made its move. They voted—by a large majority—to demolish the Palace of the Republic and rebuild a modern version of the Berliner Schloss.

At the end of January 2006 the demolition crews rolled in. This was despite the fact that two-thirds of the German population had voted to preserve the building in an informal referendum (!). But the decision was made.

Here’s an interesting twist: the steel from the Palace wasn’t just scrapped. It was repurposed and used in some pretty iconic projects, including the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which is now the tallest building in the world. Finally, in June 2013, the foundation stone for the Humboldt Forum was laid on the same spot where the Palace once stood.

Palace Paradox

The seven years between laying the foundation stone for the new Berlin Palace and its grand opening — right in the middle of the pandemic — also happen to be when we start seeing cracks in Germany’s Erinnerungskultur, or culture of remembrance, and in its politics.

2013 — that’s when the AfD was born. Then came the migrant crisis of 2015-16, which split the country down the middle. And after decades of focusing almost exclusively on the Holocaust and WWII war crimes, Germany finally began to reckon with its colonial past — a chapter it had never really taken full responsibility for. Ironically, the new palace they were building became a symbol of that forgotten history.

And speaking of symbols, this palace had something else in common with its GDR predecessor: a skyrocketing construction bill. Costs ballooned to over 680 million euros—or almost 740 million US dollars.

When the Humboldt Forum finally opened its doors in 2020, it wasn’t without controversy. There were protests, heated debates, and more questions than answers. The Forum now houses the Ethnological Museum, the Museum of Asian Art, a permanent Berlin Exhibition, and the Humboldt Lab.

Then, a year later in 2021, Germany made a historic move. It acknowledged the genocide it committed between 1904 and 1905, when the Herero and Nama peoples in what is now Namibia were nearly wiped out. In a deal with Namibia, Germany agreed to pay 1.1 billion euros in reconstruction aid—marking the first real step toward reparations for its colonial crimes.

In 2022, Germany signed another agreement—this time with Nigeria, committing to return the Benin bronzes, priceless cultural artifacts looted by the German Reich during the colonial era. And wouldn’t you know it? One of the first major exhibits at the Humboldt Forum showcased these very bronzes, alongside other treasures that are set to be returned to their rightful owners—countries that, when the old palace stood, were European colonies.

So the new Berlin Forum, this shiny palace, isn’t just a place to display ethnographic collections anymore. It’s become something much more — a place to confront the paradoxes of a national history that hasn’t really been fully addressed until now.

In 2023, this situation got a sharp, sarcastic twist. In his bestselling pamphlet, The East: A West German Invention, literary scholar and columnist Dirk Oschmann, himself born in the DDR, summed up all of these contradictions with a pointed critique.

The reconstruction of the Berlin Palace as the "Humboldt Forum" is a striking and insidious example of radically rewriting and overwriting history.

What was done here: A truly ugly, politically, ideologically, and symbolically highly charged building of the GDR, the "Palace of the Republic," was replaced by architectural eclecticism, which not only deliberately overwrites and erases the once visible, concrete history of the GDR from the cityscape, as if this historical phase had never existed, but also connects directly to the German Empire in a monumental gesture.

That Empire, mind you, which waged colonial wars, committed genocide against the Herero and Nama in present-day Namibia, and later started the First World War. For years, African art treasures, i.e., colonial looted art, were then exhibited in the "Humboldt Forum."

This demonstrates thoughtlessness and a lack of historical sensitivity. Is this Empire supposed to be the better German past, one that we should connect to and believe worthy of such pompous commemoration?

This thing now stands permanently in the heart of Berlin as a sign of historical-political failure, the extent of which has only recently been brought into general consciousness by newer debates about "reparations" and the return of art treasures, which, by the way, have existed in France and England for much longer. With beautiful regularity, the West is outraged when it is called a colonizer, yet it constantly uses the language of colonizers and follows up with corresponding actions.

From: Dirk Oschmann, Der Osten: eine westdeutsche Erfindung, 2023

And then came the final twist in this whole mess of contradictions, controversies, and simmering resentments — just last year, in 2023. To fully recreate the palace’s cupola and bring back eight statues of prophets, just like in the original Castle, the Berlin Palace Friends' Association launched a donation drive. Their pitch? That this was about 'healing' the cityscape—making Berlin whole again.

Money flooded in. But then the bombshell dropped: journalists uncovered that many of the donations were coming from right-wing extremists. Despite the outcry, the Humboldt Forum Foundation went ahead and accepted most of the funds. And now, those eight prophets stand proudly atop the building — symbols, for some of the donors at least, of a reborn, white, nationalist, Christian Germany.

It’s wild, right? But it’s true. And this has only added fuel to the fire of a growing nostalgia for the Prussian Monarchy, stoked by fringe groups like the Reichsbürger. These folks openly reject everything Germany became after 1918 and dream of restoring the empire.

The idea that the Berlin City Palace, now the Humboldt Forum, could be co-opted as a symbol of a right-wing agenda feels, frankly, ridiculous. And yet, here we are in 2024, with this palace being pulled in every direction — each side trying to mold it to fit their own vision of Germany’s past, present, and future.

Today, tomorrow.

The Humboldt Forum has become a space that reflects on its own past. There’s an exhibition on its predecessors — that inspired this post — and visitors can cast votes or share memories — many of them surprisingly positive — about life in the DDR.

But beyond all the debates, the palace has somehow become part of the Berlin landscape, and apparently, tourists love it. Just last year, in 2023, the Humboldt Forum ranked as Berlin’s fifth most visited attraction, drawing in 1.7 million visitors. The top spot still goes to the zoo, with a massive 3.8 million visitors.

But what exactly are people flocking to see? Well, it’s not the ethnographic collections. One of the biggest draws is actually the rooftop, but not because of the Bible prophets standing there. No, it’s all about the panoramic view of the city. It’s a much cheaper way to see Berlin from above compared to the TV Tower, and there’s a bar where you can enjoy a decent aperitif while you’re at it.

And the other big hit? An exhibition about the city itself. But this is Berlin, so naturally, the standout attraction in the Berlin Global exhibition is... the door to the original Tresor Club. Yeah, the door of the legendary club that opened in 1991 in the basement of an old bank building on Leipziger Straße, close to Potsdamer Platz. That door is basically a symbol of Berlin’s rise as the world capital of techno music.

In any other city, that door would probably just be scrap metal. But this is Berlin. And since this is Berlin, there’s no doubt the Humboldt Forum will eventually find its own place in the city’s identity — though it’ll likely be in a way none of us could have imagined.

The exhibition at the Humboldt Forum.

Blown Away: The Palace of the Republic

at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin,

Fri, 17 May 2024 – Sun, 16 February 2025

Share this post