This post and its podcast is also available in Italian and German:

Putin’s war against women didn’t begin on February 24, 2022. It started long before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It started before Crimea, before 2014. And it doesn’t only happen in Ukraine.

It’s happening inside Russia, too. Through laws. Laws against women’s rights. Laws against LGBTQ+ people. Laws obsessed with birth rates. Through stories that glorify the strong man, the macho hero, the obedient wife. Through silence and tolerance toward gender-based violence—especially at home.

But Putin didn’t invent this war: he inherited it from the Soviet Union. With its rules of engagement in war. With its imperialism and colonialism.

In June 1940, the Soviets entered Estonia. Two months later, Estonia was formally annexed to the USSR. Then came the Nazis. Then, in 1944, the Soviets again. The second Soviet occupation began. This time much more brutal than the first. And here too, as during the entire so-called Great Patriotic War, the Soviet Union unleashed its war against women.

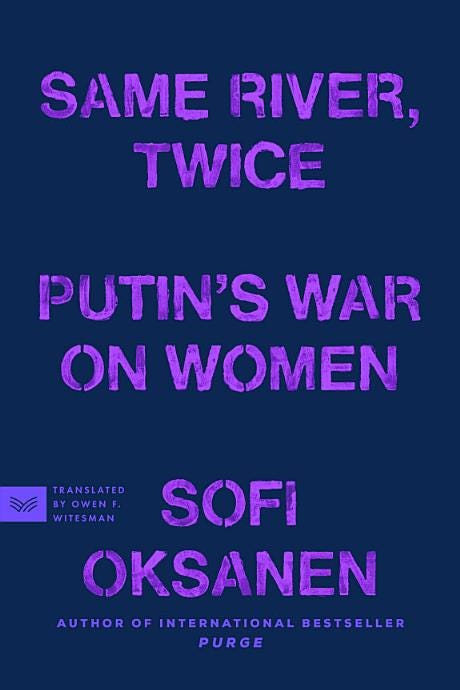

That’s where the book Same River, Twice: Putin’s War on Women begins. With the story of one Estonian woman— the great-aunt of Estonian-Finnish writer Sofi Oksanen. Oksanen’s book came out in Finland in 2023. Translated between 2024 and 2025 into several languages. Today I’m talking about that book.

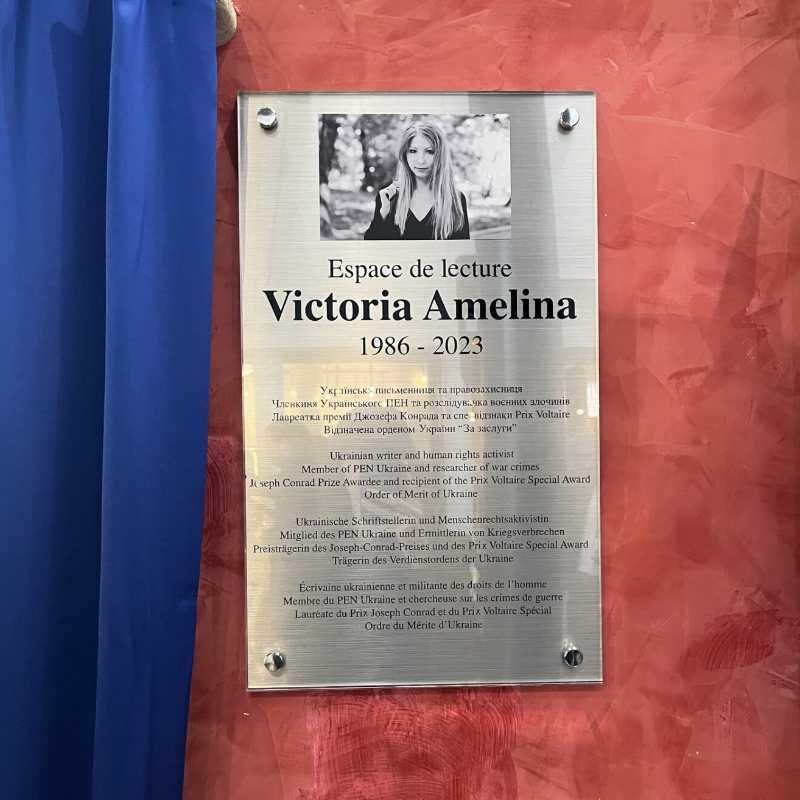

But also about another one, released worldwide in 2025. It is the posthumous text of Viktoriia Amelina: Ukrainian writer, poet, activist. Her killing by the Russians made news around the world on July 1, 2023. Her unfinished work is called: Looking at Women Looking at War: A War and Justice Diary.

Two books that deserve to be read together. They are connected by one shared thread, in three words: Women. War. Justice.

The justice Amelina sought—documenting the lives of Ukrainian women who resisted and worked to help fellow Ukrainians, to save both lives and memories.

The justice Oksanen demands—for every woman crushed under Russian imperialism, including women of past generations.

The Voice That Never Returned

“My great-aunt was not born mute.”

So begins Same River, Twice: Putin's War on Women.

In 1944, during the Soviet reoccupation of Estonia, Oksanen's great-aunt was taken away. Soviet officers. Interrogation. An entire night. She returned home appearing physically unscathed. But she never spoke again. Only two words: "Yes, get away." Whatever she was asked. Always the same answer: "Yes, stop."

She never married. Had no children. Met no one. Spent the rest of her life with her aging mother. The family understood. Oksanen understood. She was raped. Sexually tortured. She became mute.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Oksanen had déjà vu. It felt like the 1940s all over again. Someone pressing “replay”, over and over. That haunting silence from her childhood—her great-aunt’s silence— became a voice inside her head. Became a reason to write. Became this book.

The Pattern Emerges

In Same River, Twice, Oksanen traces the use of sexual violence by Russian soldiers in Ukraine. Not only there, but as part of a long, well-documented, brutal pattern. She connects Ukraine with Rwanda. With Bosnia.

She explains how evidence collection and legal frameworks have evolved through successive trials and tribunals. In Ukraine's case, evidence collection began almost immediately after 2014. Professional, systematic, determined.

And yet— almost nothing happened. Even when perpetrators filmed themselves. Even when the crimes were recorded, stored, archived.

Take Stanislav Assejev. A journalist. Kidnapped by the Donetsk militia in 2017. Imprisoned in a secret Russian intelligence prison. The "Dachau of Donbass." The torture methods using electrodes. Tools specifically designed for sexual organs. Not for information, but for the amusement of the guards.

Everything inflicted on the journalist was filmed. Distributed. Hundreds of hours of footage. Terabytes of evidence. Assejev was released in a prisoner exchange in 2019. His jailers never faced trial.

This was a test. Tragically successful. "Can these individuals film their crimes for years without consequences?" The answer is yes.

Oksanen recounts several cases. But her goal is deeper. She dives into the "why" of these sexual crimes. Where does this violence originate? How?

The book zooms out. The roots of this violence in Russia. Sexual violence as a weapon. The war against women stems from Russian imperialism and colonialism.

Western Europe rarely talks about Russian colonialism. Too busy with its own.

We've overlooked Russia's colonial expansion. Siberia. Crimea. The 18th and 19th centuries. The long history of subjugating indigenous populations. Destroying their cultures. Languages. Customs. Exploiting their labor and resources.

But there's more to explain our ignorance. Even our western language plays along. How many times have we called non-Russian artists “Russian”? Nikolai Gogol. Kazimir Malevich. The list goes on.

Oksanen explains all this— not like a scholar, but like someone who lived it. She’s half-Estonian, half-Finnish. She knows what it means to be part of an internal colony. Several chapters in her book are like a crash course in Russian colonialism. For those of us who were never taught.

The Myth That Justifies Everything

But the core of her book isn’t what happened. It’s why. Why do Russian soldiers so readily become war criminals?

The answer lies not in psychology or anthropology. It lies in the myth of the Great Patriotic War. In Russian logic, the primary crime committed by the Germans was not the Holocaust. It was the attack on the Soviet Union. Under this story, everything Soviet soldiers did to win— including mass rape— was justified. And still is. Under the same logic, “denazification” of Ukraine means erasing anything that threatens Russian empire.

This pattern leads directly to today's war against Ukraine.

In December 2022, the Duma began drafting a law. It lifts accountability for crimes committed in Russian-occupied territories. If committed "in the interest of the Fatherland." Summer 2023. The Duma passed another law. Participants in the Ukraine "special operation" get protection from prosecution. For "small and medium-sized" crimes.

The crimes of soldiers are transformed into heroic deeds.

Colonial Tools of Control

Is this enough to justify the torture in Donetsk? The violence against women in all territories occupied by Russians?

History teaches us: any human being can commit certain acts when they no longer see the other as human. Dehumanization of the enemy. Of occupied civilians. A key aspect of colonial powers.

Oksanen pinpoints the heart of the Russian problem. It is the last remaining colonial empire. Still applying colonial practices. In its internal colonies. In countries it continues to subjugate as external colonies.

She examines Russian colonialism aspect by aspect in its historical continuity from the colonization of Siberia and Crimea in the 18th and 19th centuries through and beyond World War II.

Among colonial practices, systematic violence is a typical tool of control. Particularly sexual violence. So yes, rape is used as a weapon. But also as a message. As policy. And it is systematic. It’s meant to humiliate, terrorize, and fracture families. Women are raped in front of relatives. Mothers, wives, sisters are targeted to send a message. It’s also demographic. Rape to traumatize, thus preventing women to have future births. To castrate, to sterilize, to erase.

The Most Shocking Aspect

There is an aspect even more shocking than all the others. For which the colonial mentality alone cannot provide an explanation.

How can a woman support this?

In spring 2022, 27-year-old Russian soldier Roman Bykowski called his wife Olga from the front. The intercepted phone call reveals that the wife allowed her husband to rape Ukrainian women. Provided he used a condom. Olga and Roman have a child. His mother-in-law? Also proud of her son-in-law, the war hero. And she’s not alone.

Other mothers, wives, girlfriends—listen, nod, support. Like Tatjana Solovyova, discussing on the phone from Kaliningrad with her soldier son about the best methods to torture prisoners. There’s money, too. Soldiers bring income. Or compensation, if they die.

And when girls like 16-year-old Daria Fischun speak out— raped during the Russian occupation of Kherson— the worst abuse online comes from Russian women. Many of them mothers themselves.

When Russian Mothers Once Rebelled

But it wasn’t always this way. During the Soviet-Afghan war, as casualties mounted and information was tightly controlled, mothers of conscripted soldiers began to organize. Seeking information about their sons. Protesting conditions and lack of transparency.

This grassroots activism led to the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers. Their public protests contributed to growing disillusionment with the war. A factor in shifting public opinion against the conflict. Against the Soviet regime's militarism.

And Putin learned the lesson. So, when he came to power, he waged war on women immediately.

Before the laws, came the narrative: feminism is a Western import designed to destroy the soul of the Russian nation.

The mission of this nation? To protect the world from the "globalist, liberal, Western virus"—of which feminism is considered one of the most detrimental expressions. Russian exceptionalism.

In Russia, the mission seemed accomplished. In 2017, violence in relationships was practically legalized. One Duma member, a woman, said punishing a “simple slap” was absurd. The Orthodox Church backed her. The continuity between Putin and Stalin lies in this. Completely reversing proto-Soviet women's emancipation. When Soviet women were the third in the world to receive voting rights.

Putin acted swiftly, using ideology and laws. The ideology comes from philosopher Dugin. Then come the laws. Then the incentives.

Having children to send to war is a financial investment. It pays well. As long as the state can afford it. For the internal colonies—those regions we've heard about because the most crude and brutal soldiers come from there—this investment is worth gold.

Ukraine: The Existential Threat

Ukraine became an existential threat to Russia also because of its women's emancipation. Post-2014, the changes came fast. Education. Leadership. Visibility. Rights. And now? Women fight. At the front. On the ground. In the courts. Online. Everywhere.

Euromaidan was a female nightmare for Putin. The weapon of disinformation and defamation was fully deployed.

In 2014, Gazprom’s TV channel aired Furies of Maidan: Sex, Psychosis, and Politics.

A “documentary” that mixed porn clips and “expert” interviews. Its thesis? The Maidan uprising was caused by sexually frustrated Ukrainian women. Because what else could explain women demanding justice? So no—this invasion isn’t about territory. Not about protecting Russian ethnic minorities. It’s about control. It´s about silencing voices. Especially women voices.

Fighting for Future Voices

Towards the end of the book, Oksanen notes that we often hear Ukraine is fighting for our democracies. Instead, she asks:

“How often have you heard that Ukraine is also fighting in this way for the future of women and minorities? That Ukraine is fighting for its daughters and sisters and female partners? That it is fighting for all future generations of women and girls? So that they do not lose their voice, like my great-aunt.”

On March 5, 2022, just days after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Sofi Oksanen and Viktoria Amelina met on Zoom.

They knew each other through PEN International. They were colleagues. Friends. Writers who believed in truth, language, and justice. Sofi reached Viktoria in Lviv, where she stayed after moving her mother, son, and family to safety in Poland. Viktoria had just returned from Egypt, where she had gone for a short holiday with her son. The war began while she was there.

"During the days I'm here because the war for me started when I was on vacation. I was on vacation in Egypt. Right now it seems like it was a completely different past life that we had and I had fun with my family. And then on February 24th we tried to board the plane back home” […] "So we spent two days trying to get back home because we wanted to. Of course I left my son with family in Krakow so my son is safe and I came back to actually volunteer and this is what I'm doing now trying to help as much as I can mostly not as a writer not as a speaker but as a person who can connect people who can sort out humanitarian aid etc."

Coming back to Ukraine was a deliberate choice. Not easy to fulfill. But she came back. And started to help.

It is a conversation between two engaged women—intellectuals who believe in the power of words. They discuss the Ukrainian language, the country's history, and its literature. But they also address what Ukraine desperately needed from the beginning: to save lives. Listen again to Viktoria's voice:

"But I think the most important thing is still for people in Finland and people across Europe in Canada, United States to get to the streets and actually ask your governments to help us with our air defense. We do need no-flight zone over Ukraine, we do need you to interfere because right now while we are speaking Russian forces are actually destroying Ukrainian cities."

"They aimed their missiles at civilians, hospitals, schools, churches, everything and it's so devastating and we will win anyway but depending on whether NATO countries help us and close the sky or not, we will have either thousands people dead or millions. So it is really up to your governments now and if you could take some hours to get to the streets to get to the squares and demand they help us that would mean a lot to us, that would actually save our lives."

We know how it ended.

Ukrainian skies were never protected. No fly-zone. No Western jets intercepting Russian missiles. No one wanted to risk a direct clash with Moscow. We didn't stop the bombings. We didn't stop the death toll. We didn't save Victoria Amelina.

In the months that followed, Viktoria became a war crimes documenter. She traveled across Ukraine, collecting evidence. Listening. Recording. Helping. Then, on June 27, 2023, while having dinner at a pizza restaurant in Kramatorsk, a Russian missile struck. She died days later, at age 37. She left behind a son, a mother, a sister, and an unfinished book—60 percent complete. This book: a war and justice diary.

Looking at Women Looking at War: a War and Justice Diary.

Victoria Amelina could have stayed in Poland. Or maybe Berlin. She had friends in both. She had been to festivals, had places to go.

Instead, after making sure her son was safe with relatives in Kraków, she returned to Lviv. She evacuated her mother and others. Then she stayed. First in Lviv. Then in Kyiv. Then, all over Ukraine. No longer as a writer. No longer as an organizer of literary festivals. But as a volunteer war crimes researcher.

For some time she stops writing. She can no longer find the words. Then, between one mission and another, she starts again. With poetry. Soon she begins to realize that she could do something more significant through writing. She explains why in the introduction to the book:

“I see this book as a kind of detective story. Since the war began in 2014, and with the full-scale invasion now, I, along with millions of my fellow citizens in Ukraine, have been in search of one thing: justice.”

She was looking for proof. Photographing bombed libraries. Recording testimony in destroyed schools. Following traces of war, not for the headlines—but for justice.

“This same urge also slowly turned me back into a storyteller… so that I might tell you the story of Ukraine’s quest for justice.”

A Gallery of Extraordinary Women. And more.

What kind of book is Looking at Women Looking at War? It defies labels. It’s part field notebook. Part diary. Part poetic reflection. Part legal brief. But above all, it’s a collection of portraits. Women’s portraits.

These are the women Victoria meets as she travels with Truth Hounds—the NGO documenting Russian war crimes. Women who resist. Women who rebuild. Women who, having a successful job, feel compelled to change it. To do more for their country.

Like Evhenia Zakrevska. A high-profile human rights lawyer. She represented families of protesters killed in Kyiv in 2014. Then she left it all to enlist in the Ukrainian army. Amelina writes:

“She will learn how to stop tanks with a Kalashnikov.”

Or women like the mysterious Casanova. The nickname of a seasoned war crimes researcher. Casanova—the same age as Amelina, 37, with a son, long hair, and a dream of writing a book. She'd been documenting atrocities since 2014. She wanted to quit, to pursue a personal dream: buying a small house with a garden. A casa nova. When the full-scale invasion began, she abandoned that dream. She returned to lead the research team.

Casanova is the reason Amelina, too, becomes a war crimes documenter. On April 9, 2022, Victoria called her and asked: Do you need volunteers? Casanova wasn't sure. But Victoria insisted.

She trained. She learned how to talk to survivors. How to collect evidence. How not to cause more pain. A new chapter began. She also started reading international law. The Rome Statute. The Genocide Convention.

Then there's Tetyana Pylypchuk, director of the Kharkiv Literary Museum. When the bombs started falling, she saved the archives—Ukrainian manuscripts and first editions. She stuffed them into black garbage bags and, with the help of local soldiers, boarded a train west.

She was saving the works of the Executed Renaissance—writers murdered in the 1930s, erased by the Soviets, forgotten by the world.

“They are the weird ones, Ukrainians by choice… Their archive would mean nothing to the rest of the world… But for people like Tetyana, they mean the world.”

Tetyana grew up reading Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Bulgakov. So did Amelina. Both spoke Russian, and Tetyana majored in Russian literature. Then, Tetyana discovered her hometown had a hidden Ukrainian literary history she had no idea about. She joined the Museum. Resolved to help the rest of Ukraine learn the truth about its twentieth-century writers.

In Berlin, a year later, Amelina would explain this complicated relationship with Russian: the difference between being Russian Ukrainian, who legitimately have Russian as their native language, and the many Ukrainians who inherited Russian as the first language. As the legacy of imposed russification.

Who ended up, like Amelina, switching to Ukrainian as an act of reparation:

“To me, it’s just my personal act of justice… I had to switch to Ukrainian. So I did.”

In the Liberated Villages

The book proceeds in episodes. Staccato-paced short stories of sorts. Each titled after a particular woman. With her war crimes research team, Amelina is often the first to visit several villages that had been liberated after Russian occupation.

In September they visit the village of Kapytolivka. Part of the Kharkiv Oblast. Arriving just a few days after its liberation. In the schoolyard, a landmine marked with a fire extinguisher. The librarian tells her, casually, everyone knows to avoid it.

That librarian is Yulia Kakulya-Danylyuk. She kept the library open. Despite the danger—when a single wrong word could cost your life—she kept a war diary. Written in blue ink. The neat handwriting of a teacher’s hand.

“The war began in Ukraine. Russia invaded us…” marks February 24, 2022.

On March 12, 2022, Yulia wrote:

“It’s incredible how quickly one can learn to live in new conditions… I hear rockets fired and I chop wood.”

Under a Cherry Tree

Across the village, someone else was writing too: Volodymyr Vakulenko, a writer and friend of Amelina. He had the chance to flee. He didn't. He stayed. And recorded the start of the invasion with poetic lines:

"The sun was not in a hurry to warm up the land. Slowly, timid tulip sprouts emerged from the ground. No one covered them to protect against the frost. After the bombed-out buildings in the city, there was no time for flowers."

Both librarian and writer note how quickly they have adapted to the horror. Volodymyr writes:

"You get used to everything; the main thing is who you remain amidst all this. The 'Grad' explosions stopped bothering me at all."

On March 24, 2022, he is abducted by the occupiers. Amelina interviews the father of Volodymyr Vakulenko. Who kept waiting since the day of the abduction. The truth soon comes out. Vakulenko was killed by his abductors a few days later. Shot with a pistol. His body put in a mass grave outside the village of Izyum.

But he had hidden his diary. Fearing they’d take it. Exploring palm by palm Volodymyr's house garden, Amelina found it. Under a cherry tree.

“I wasn’t afraid of landmines. I was terrified not to find that diary.”

His final entry, March 21, 2022:

“Putin is a Dickhead.”

Saving Words, Saving Memories

This is, too, a way to fight that war. Saving words. Saving memories. Russia’s war doesn’t just target people. It targets culture. The museum of philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda? Destroyed. Shevchenko University? Damaged. Museums, libraries, galleries, concert halls? More than 514 cultural sites were hit by the time Amelina was writing.

On October 10, several cultural objects were also damaged in Kyiv. And still, Kyiv shines:

"Kyiv looks as beautiful as it always has. Maybe even more so. It and why they will never have it.”

“I pour myself a glass of wine. It's certainly too early for alcohol, but I feel like it's almost the end of the story, and I should mark it. The neighbors won't judge me: they're all under attack again, but the heroines of my diary are not scared at all. One of them just received a Nobel Peace Prize. Another is finishing her book about Irpin and Bucha. All of them are winning a fight. For a moment, it seems that justice is not only possible but inevitable simply because I can eventually define it. I feel it. Standing there, defenseless but fearless, I know what justice is.”

Toward the end of the book, Amelina describes listening to yet another air raid from the balcony of her Kyiv apartment. Watching the air defense rockets respond to the attack unfolding in the city's nighttime skies. So apocalyptic yet ordinary. She observes the rockets from the window:

"I just don't fear death anymore... I imagine even how all the women I write about would finally gather at my funeral: they all are busy fighting for justice, so such an occasion is definitely the only chance. But then I remember I have yet to finish this book, watch my son grow up, and possibly even join the army in several years. So I step away from the magnificent but dangerous view and get back to writing."

Justice. That’s the word. It runs through every page.

"What is justice? Who are we willing to forgive and who not? How do we live with the awareness that those responsible for the most terrible crimes may go unpunished? How can we change this situation? What weapons do we have available to bring justice back in these dark times?”

Justice became Amelina's mission. Justice against the Russians. But also justice against the lack of recognition of the Ukrainian people and narrative.

In February 2023, five months before her death, Amelina came to Berlin. She joined a conversation about Westsplaining—about how the West kept centering Russia in the story of Ukraine. She was there not just as a war crimes researcher, but as a writer. She talked about words and how war had changed her language.

"As a writer, I can say that we don't use war as a metaphor anymore. We've stopped using many metaphors altogether—our language has become more simple and direct. I'm not much of a poet, but I did start writing poetry during this full-scale invasion because I was speechless. This short form became necessary for me to convey simple, direct messages. I speak more directly now, though I was always like that. I don't remember being a novelist in a peaceful country, as my debut novel came out in 2014, already after the initial Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea. But right now especially, I don't even have the resources to pretend, and I don't see any reasons anymore to be cautious. War is the time for sincerity."

Berlin, Pilecki Institute, February 2023

The Unfinished Book

The book was never finished. Her friends and ex-husband, Alex Amelin, curated it. It is fragmented but not broken. The book exudes sincerity and, despite everything, hope.

"Looking at Women Looking at War" is a book that will endure—like the essential and sincere pieces of poetry that Amelina began writing during the war:

Why do you look like them? Maybe you are brothers? No, our hands intertwined not in a hug, but in a fight Our blood was mixed with the soil they took our harvest from Our eyes cried with tears that turned into ice behind the gates of our warm cities we were thrown out Our language was burned alive screaming on the Maidan And we picked up the foreign one as if someone else's gun We learned from the books of our captors all the paths in the prison labyrinth Our mother cursed us to look like the murderers not like our killed father So we would die not in a slaughterhouse but in the fight So, when our fight begins Don't ask us Why do we look like those who have been killing us for so long Viktoriia Amelina, May 8, 2022 (via Darya Zorka)

Today.

On June 25, 2025, Victoria Amelina was posthumously awarded the prestigious U.K. Orwell Prize for her book "Looking at Women, Looking at War."

On March 11, 2025, the European Parliament in Strasbourg opened the Victoria Amelina Reading Space.

In the meantime, in late February 2025, the body of Viktoriia Roshchyna, a 27-year-old Ukrainian investigative journalist who disappeared in the Russia-occupied part of the Zaporizka region of Ukraine in August 2023, was brought back to Ukraine. Preliminary forensics suggest "numerous signs of torture," according to the prosecutor: burn marks on her feet from electric shocks, abrasions on the hips and head, and a broken rib. Her hair, which she liked to wear long and tinted blonde at the tips, had been shaved off. Justice. We wait.

And then there are the resistant women of Zla Mavka ("angry fairies"), a grassroots network of Ukrainian women operating in areas under Russian occupation. Taking their name from mythical Ukrainian forest spirits known for their wild and mysterious nature, the Mavkas form a nonviolent resistance movement. They emerged in Melitopol in early 2023 and remain active today. Their story is told here 👉 www.balcanicaucaso.org.

Share this post