There’s a legend in Jewish mysticism. It tells of thirty-six righteous people who exist in every generation. Just thirty-six. They live quietly, hidden from the world and from each other. Yet because of them, the world goes on. Because of them, God withholds his anger and spares humanity—despite everything. They are unknown. Ordinary. They don’t seek recognition. But without them, the world would collapse.

How many of them lived in Germany during the twelve years of Nazi rule? How many knew how to say NO? How many said YES—not to the regime, but to others? To friends, to neighbors. How many helped, hid, protected, resisted?

Very few, we often think. But maybe more than we imagine. Historians speak of at least 150,000 people. Some say 300,000. Others even 500,000. People who, in different ways, took a stand: denouncing injustice, sabotaging the regime, showing simple human solidarity. Many of them remained invisible. Unknown to others—maybe even to themselves. Like the righteous in the legend.

And how Germany remembered them didn’t help.

In West Germany, for years after 1945, resistors were often seen as traitors. Recognition came slowly. A few became celebrated, but only later. You know the names: Stauffenberg and the military elite of the July 20th plot. In East Germany, only Communist resistors were honored. The others? Ignored, or even viewed with suspicion. It took until the 2000s for many to be acknowledged. And still, much remains hidden. These stories only resurface sometimes—on anniversaries, or by chance.

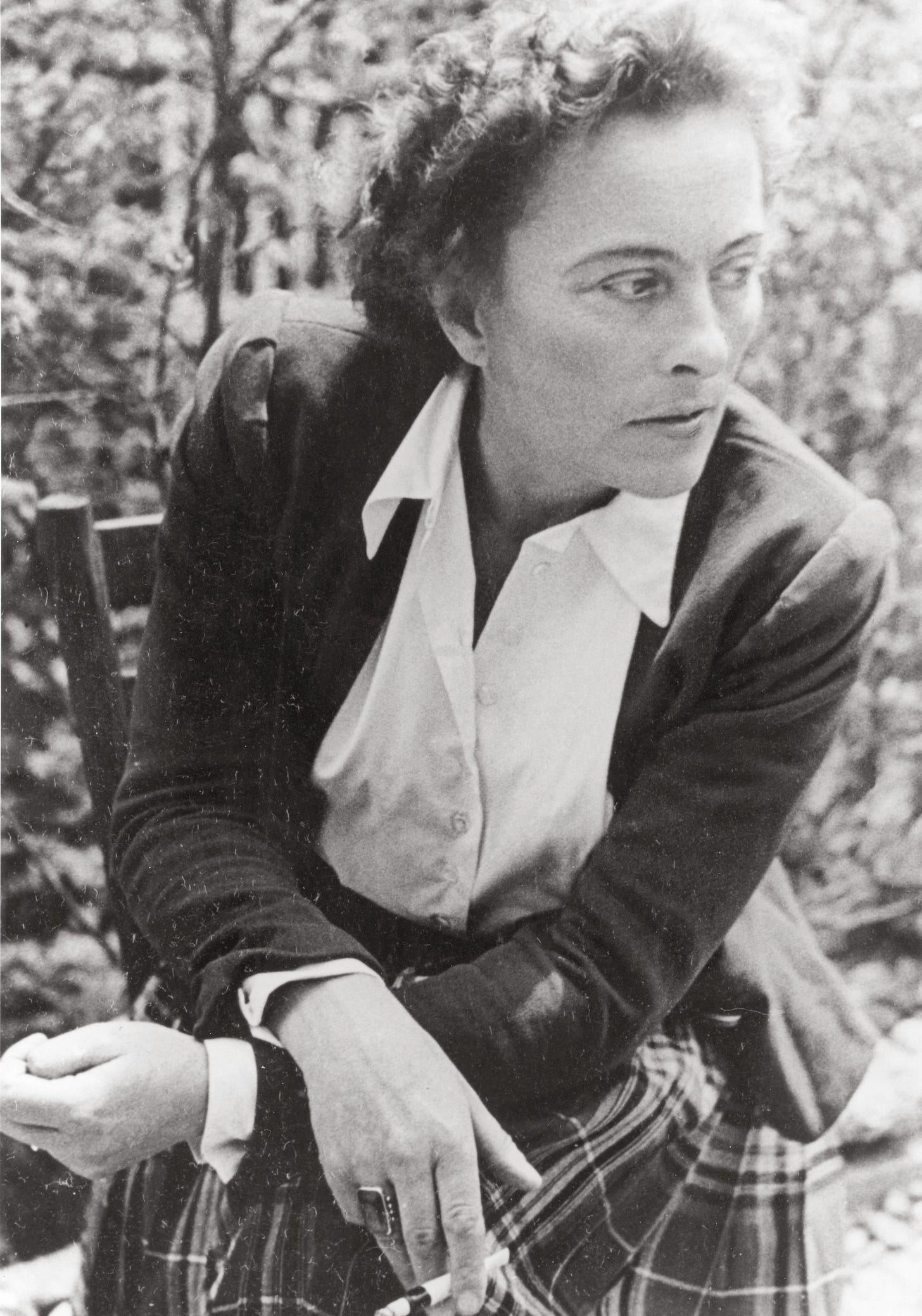

That’s how I met Ruth Andreas-Friedrich.

Her face was on a panel near the Brandenburg Gate. A striking photograph. And a quote that stopped me in my tracks. She was a journalist. An emancipated woman who loved life. And from 1938, she resisted. Around her gathered a small group of friends, without political banners. Just courage. And a strange name: “Uncle Emil.”

Today I want to tell you their story.

Follow me.

But first, listen to Ruth.

Her words say everything.

“The final victory is when the Allies march through the Brandenburg Gate. And once again, I think, as I have so often before: What a paradox that a German prays for the enemy’s victory! A strange love for one’s homeland, which can wish for nothing better than its own conquest.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich

Berlin, 18-19 April 1945: A single word against the war.

The night between April 18 and 19, 1945. Cold air. Clouds. A bit of rain during the day. Smoke still rising from bombed-out houses. Now, as night falls, the clouds mix with dust. Dust kicked up from rubble. The city smells of ash and wet stone. People crawl out of bunkers to walk home. They want a bed, even if only for a few hours.

Even the moon is gone. Only darkness. And then, in that darkness, they come out. In twos. In silence. All across the city. Men and women moving like shadows. In their hands: chalk. Paint. Brushes. Hidden in sleeves, inside coats. They are on a mission: simple, but dangerous. Write a word. One word. Everywhere.

Four letters: “N-E-I-N”. No.

These are the last days of the war. Soviet troops are closing in. The city is surrounded. Everyone knows: it’s over. Except one man, Hitler. He has decided to bring the capital down with him. A final act of madness. But not everyone follows. Not everyone wants to die for him.

So they say no. No to suicide. No to more blood. No to the Führer. No to this war. They have organized in the days before: they split the city into zones. Each pair takes one. Tonight is the night.

Among them: Ruth Andreas-Friedrich and Walter Seitz. They are friends. They are also part of the resistance. Since 1938, they’ve done what they could. Helping Jews in hiding. Forging papers. Smuggling food. Sending messages, keeping hope alive.

But this feels different. Bigger. A whole city will wake up and see “NO” written on its walls. And Ruth has been writing everything down. Since 1938, she’s kept a diary. And so, tonight, she writes:

“Somewhere in the distance, a dog barks. My hands begin to tremble. Next to me, I hear Frank breathing quickly and anxiously. Don't get weak now, I think to myself. Hesitantly, I take a few steps to the right. Between my fingers, I feel the cold corner of a mailbox. Through clenched teeth, I hastily paint N-E-I-N on the wide mail slot. The chalk squeaks. This must be how blind people feel when writing. I turn around. "Hey, it works!" I want to whisper.

No - No - No. Either we do it properly or not at all. We paint and write with focused fervor. On curbs and telegraph poles, on garden gates and advertising columns. Wherever there's something that catches the eye, we stamp our ´NO´ on it like a colored seal.” – 18 April 1945

The fear is real. Police boots echo in the streets. Sometimes they stop and pretend to kiss, to blend in. Sometimes they press against the wall and freeze. But the more they write, the braver they feel.

At dawn, the first light. They see the signs others have left. They’re not alone: the coordination worked. They are almost out of paint. Almost out of strength. And then they see it. A tall signboard, standing like a statue. On it: “The Jews are our misfortune.”

Ruth watches. Frank climbs up. Slowly. Calmly. He dips the brush in red paint. Too slowly for her nerves. She stares at the sign.

“Now he puts the brush to work. Dark red paint drips onto the pavement. It looks like blood, I think to myself. "The Jews are our misfortune!" N-O! Frank's protest gleams in hand-wide beams from the wooden bulletin board. He admires his work like an artist. "Come!" I urge. "Come!" In the dawn, we make our way home.”

That night, no bombs fall. They sleep. Almost like a sign.

The next day: part two. This time: Flyers. Short texts. Printed secretly. To attach and leave wherever someone might read. The message is clear:

“Berliners! Soldiers, men and women! You know the order of the madman Hitler and his bloodhound Himmler to defend every city to the bitter end. Anyone who still follows Nazi orders today is either an idiot or a scoundrel. Berliners! Follow Vienna's example! Through hidden and open resistance, Vienna's workers and soldiers prevented a bloodbath in their city.

Should Berlin suffer the same fate as Aachen, Cologne, and Königsberg?

NO! Write your No everywhere! Form resistance cells in barracks, factories, and air-raid shelters! Throw all pictures of Hitler and his accomplices into the street! Organize armed resistance!” – 19 April 1945

One more night. More fear. Ruth's knees tremble as she and her companion nearly get caught. Though it grows harder to continue, they complete their mission. As they place the final flyers, Ruth writes and remembers the others who lost their lives to resist:

“I feel as if I've completed a mountain climb. Body search - arrest - court-martial - gallows. To stand so close to the edge of life! How easy it is to get your head caught in the noose. I think of all of them who died for us. Will they build a memorial to Graf Moltke1 later? We are home by five in the morning.” – 19 April 1945

Ruth Andreas-Friedrich: The editor who chose Resistance.

Who was Ruth Andreas-Friedrich? And how did a feuilleton writer from Berlin become one of the most important chroniclers of everyday resistance under the Nazi regime?

She was born Ruth Frieda Mathilde Behrens, in 1901, in Berlin. Her father was a lawyer and senior military administrator; her mother came from a bourgeois background. Ruth was supposed to become a nurse, but she had other ideas—she loved books, and she wanted to write. So she began training as a bookseller and, not long after, in 1924, married Otto Friedrich, a man who after the war would become a factory director and president of the Federal Germany employers’ federation.

Married, yes—but never confined at home. Not in Berlin, not in the 1920s.

Ruth embraced the cultural electricity of the Weimar Republic capital. She launched her career as a journalist and reveled in the city’s café life—surrounded by writers, artists, musicians, and dreamers. She cut her hair short, danced through the night, and discovered early on that monogamy wasn’t for her. The marriage didn’t last. But the friendship did—and she kept the name: Ruth Andreas-Friedrich.

At this point, she wasn’t a political journalist. She wrote light features and advice columns, celebrity profiles—stories like “Greta Garbo’s debut in front of the camera.” Even after the Nazis seized power in 1933, she managed to continue working as a freelance writer for various women’s magazines.

But everything started to change in 1931, when she met Leo Borchard. He was a classical music conductor, born in Moscow to German parents. Soon blacklisted by the Nazis. He insisted on working with Jewish musicians—something that quickly made him “politically unreliable.” Ruth and Leo became partners, each with their own apartment in a modest Berlin-Steglitz building—one flat above the other. Ruth had a young daughter; Leo lived alone.

Together, they formed a circle of friends. Intellectuals, artists. Many of them Jewish. At first, the group wasn’t political. Just a fun-loving, bohemian crowd. And independent. But things changed soon. The harassment of Jews escalated. More and more friends lost their jobs, their homes, their rights. Some began disappearing into hiding. The perspective changed. Worry turned into action. Compassion became resistance.

Her circle of friends—the clique, as she affectionately called them—grew into a resistance network. They helped people hide, find food, forge documents, survive.

Ruth began to write. Her diary became a chronicle of terror and solidarity, of loss and dignity, of unyielding moral clarity in a time of madness.

It begins in September 1938, when Hitler escalated pressure over Czechoslovakia during the Sudeten Crisis. On September 27, just days before the Munich Agreement, Ruth found herself in front of the Reich Chancellery, watching Hitler’s troops parade. She was surrounded by silence—not celebration. A city holding its breath.

“There is no doubt that Hitler wants war. We said ‘no.’ We thought ‘no.’ We mean no. And we don’t want to.” – 27 September 1938

And after the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 9, 1938, those thoughts became action. The clique went underground. Ruth lived a double life—editing women’s magazines on the surface and running her apartment at Hünensteig 6 as a safe house, a meeting point, a nerve center of quiet resistance.

That was the beginning of a new chapter in Ruth Andreas-Friedrich’s life. One of courage. Of danger. Of integrity. And above all, one of memory—because she believed that some stories must be told, even when writing can cost you your life.

The war begins. First, against one’s own people. Then, against the world.

Berlin, 8th November 1938. The news spreads fast. A young Jewish emigrant in Paris has shot a German embassy official. The press explodes. Headlines scream. Ruth writes it down in her diary. Andrik — her lover, Leo Borchard — has a feeling. This will be used. It will turn into something ugly. He’s right. The next day, it begins.

November 9th, 1938. Kristallnacht. The Night of Broken Glass. Windows shatter. Homes burn. Synagogues are set on fire. People vanish.

On the morning of the 10th, Ruth opens her door. A Jewish friend, a lawyer, is standing there. He needs a place to hide. She lets him in. Then she heads to work. To the editorial office. To see what people are saying — or not saying. Her boss says almost nothing. One editor grins. He’s enjoying it. Only one voice trembles with rage. A young editor. “Karla” (real name: Susanne Simonis):

“We should actually spit on ourselves for standing here like this and not opening our mouths!” (...) “Naturally, we should spit on ourselves. But who benefits from opening your mouth if they grab you by the collar in the next moment and quietly make you a head shorter? Martyrs need an audience. Anonymous death as a victim has not helped anyone.” – 10 November 1938

It’s a moment of truth. Two things become clear to Ruth. You must do something. But not foolishly. Words are not the best strategy. Not now. That’s when the idea of silent resistance takes shape. The understanding that the war has already begun. Not just the one everyone fears. But the one at home. A war against neighbors. Against Jews. Against friends.

Early 1939. Ruth spends her days finding people. Helping them escape. Smuggling out savings. Searching for those already arrested. By then, the next enemy is chosen: Poland. In Germany the new watchword is Danzig The war machine is warming up.

In August 1939, Ruth and Andrik are in Sweden. Friends beg them to stay. It’s safe there. But they return to Berlin: they step off the train. They see it. Everything has changed. General mobilization. The war begins. Then, November 1939. First attempt to kill Hitler. Failed.

December 1939. First Christmas of war. And with it, the first “Hitler Christmas”. Yes, they even rewrote the carols:

“Silent night, holy night,

All sleeps, alone watches

Only the Chancellor in faithful keeping,

Watches well over Germany’s thriving,

Always mindful of us.

Silent night, holy night,

All sleeps, alone watches

Adolf Hitler for Germany’s destiny,

Leads us to greatness, to fame and to happiness,

Gives us Germans the power.”“Christmas in the Third Reich” by Fritz von Rabenau2

Andrik reads it. He tosses it onto the kitchen table. “What do you think of the artwork?” he says. Ruth is shaken. She writes.

“The intellectual catastrophe is much worse than the material one could ever be. The nonsense, falsification of history, distortion of truth and artistic slander that has been hammered into people’s heads for many years will not easily be removed.

Each of us bears somewhere the stamp of the Third Reich. And even the downfall of the regime will not turn Nazis into democrats, mass men into personalities.

Hitler has accustomed the people to ecstasies. There always has to “bang” somewhere. One always escalates into excess. The unleashing of all values has penetrated even everyday language.

Nothing is simply called “beautiful” anymore because it is beautiful, simply “great” because it is great. What doesn’t present itself as “enormously great,” “supernaturally beautiful,” “uniquely wonderful,” tastes bland and powerless.”

The damage is everywhere. But most of all — In the language. The language.

1941: invincible, but not for long.

In 1941, Hitler seemed still unstoppable. The German army marched deeper into Europe. Victory after victory. Strength after strength. And so, the regime grew bolder. Harsher. Crueler.

In September 1941, a new law came. All Jews had to wear the yellow Star of David. A symbol meant to isolate. To shame. On the streets, even children joined in the mockery. The laughter. The insults. But Ruth noticed something else too. And she wrote it down:

“The majority of the people are not happy about the new regulation. Almost everyone we meet is as ashamed as we are. And even the children’s mockery has little to do with serious anti-Semitism. They mock because they expect to have some fun from it. A fun that costs nothing, since it is at the expense of the defenseless.” — September 1941

And then—slowly, silently—the wind began to change. By December 1st, things were no longer so triumphant. Ruth writes: the Germans are still in front of Moscow. And Leningrad. No more talk of lightning victories. Instead, signs of panic. And anger. Because Stalin, they say, has armed civilians.

But there is worse. Seven days later, a neighbor disappears. Margot Rosenthal. A Jewish woman. She is taken away at dawn. No warning. The neighbors ask questions. But no one knows anything. The next day, headlines scream: “Japan at war with the USA and England!” But Ruth doesn’t care.

“We hardly listen. It doesn’t interest us. At the moment, only one thing interests us: Where did they take Margot Rosenthal?” — 8 December 1941

A few weeks later, news comes. Margot is in a ghetto. Near Landshut. She writes. She begs. For food. For help. She cries all day. Andrik and Ruth act immediately. They send what they can. Christmas is near. But Ruth cannot celebrate.

“There should be no Christmas trees as long as there are people in the world who have to cry all day long. In eight days, the fourth year of the war begins. The tenth year of our state-sponsored anti-Semitism.” — 24 December 1941

Connecting the Resistance. The birth of “Uncle Emil”.

From 1942 onwards, Ruth Andreas-Friedrich and her 'clique' stepped up their efforts to help as many people as possible. The disenfranchised and persecuted, especially Jews, were hidden in rotation. Ration cards were stolen for those in hiding, known as 'U-boats'. They forged false papers for those trying to escape. They also supported political prisoners and cared for their families.

However, it was becoming clear that they needed better coordination. Not just within their own group, but with others across the city. Ruth recounts one of the key turning points:

“One thing is certain,” Frank declares emphatically. “The time of loners is over. The strong are no longer the most powerful alone. We must form a shock troop. Across all of Berlin. In every district, our people must be positioned. Conspiratorial comrades, on whom one can rely unconditionally. The old circle is not enough. – 1 August 1942

They began referring to their network as “Uncle Emil”, a code word to be shouted in case of sudden danger. The mission expanded. It was no longer just about helping fugitives; it also involved sabotaging factories and train lines, spreading messages and linking up with other resistance cells.

In autumn 1942, Ruth came into contact with members of the Kreisau Circle3, one of the most active resistance groups in Nazi Germany.

The group brought together an unlikely coalition of middle-class intellectuals, including doctors, lawyers and writers, as well as working-class members such as a master confectioner and a printer. Later on, they also included communist-leaning workers. For a brief period, the group also included Cioma Schönhaus4, a gifted graphic artist and passport forger. They were acting in a changing political landscape:

“The Russians have broken through the front. In Africa, the Brits are making enormous progress.” — 22 November 1942

But the worse it got for the German army, the worse it got for the Jews. Ruth and her group didn’t yet know it, but the Wannsee Conference in January had already decided on the “Final Solution.” In December, those who still could, went into hiding. The rumors were no longer just whispers:

“Jews are going into hiding in droves. Terrible rumors are circulating about the fate of the evacuees—mass shootings and death by starvation, torture and gassing. No one can voluntarily expose themselves to such risk. Every hideout becomes a gift from heaven. A rescue from mortal danger. The Ring Association passes lodgers back and forth between them. You take them one night – we take them the next! Long-term guests are suspicious. The constant coming and going is already making the neighbors distrustful.” — 2 December 1942

And Ruth writes what so many dare not say out loud:

“Are we defending the evacuation of the Jews to Russia’s steppes? The disgrace of the concentration camps? The misery of starving prisoners of war? Are we defending Hitler’s megalomania? Or Goebbels’ lust? Are our men being shot to pieces by the millions so that Mr. Göring can build himself new palaces?” — 22 November 1942

1943: Total war against humanity.

“Stalingrad has fallen. Three hundred thousand German soldiers will not return. Their commander, General Paulus, is alive. Why do those who arrange the war always survive it? And almost never those who have to carry it out?” — 6 February 1943

The deportations of Jews are in full motion. Someone must pay for the defeat at Stalingrad. Ruth goes from house to house, looking for people she knows. But often finds only empty rooms. Or places already destroyed by the Gestapo. Then comes the worst. On 18 February, Goebbels gives his most fanatical speech:

“Goebbels holds a "rally of fanatical will" in the Sportpalast. "For the salvation of Germany and civilization!" "Only the strongest commitment, the most total war," he implores his listeners, "can and will banish the danger." — 19 February 1943

And total war means also the total destruction of the internal enemy. The final liquidation of the Jews. By the end of February, deportations and suicides have already reduced the number of Jews in Berlin to about 26,000. Then comes the so-called Fabrikaktion5 From Ruth Andreas-Friedrich’s diary:

“Since six o'clock this morning, trucks have been driving through Berlin. Escorted by armed SS men. They stop in front of factory gates, stop in front of private houses. They load human cargo. Men, children, women. Under the gray tarpaulins, disturbed faces crowd together. Wretched figures, crammed together and jumbled like livestock. More and more keep coming, are pushed into the overcrowded wagons with rifle butts. In six weeks, Germany is to be "Jew-free." We run around. We telephone. Peter Tarnowsky - gone. The publisher Lichtenstein - gone. Our Jewish seamstress - gone. Our non-Aryan family doctor - gone. Gone - gone - gone! All gone!” — 28 February 1943

Allied bombs begin to fall on Berlin. Ruth writes about them. But more than anything, she writes about her fellow citizens. They don’t understand why they are being bombed.

“The path from cause to effect is a long one. Very few know how to walk it. Hardly anyone understands that today's consequence can be yesterday's cause. The cause Coventry, the cause Dunkirk, the cause Jewish atrocities, razing cities and concentration camps. The broom that sweeps Germany Jew-free will not go back into the corner. And the spirits that were conjured up will now not be gotten rid of.” — 2 March 1943

Around this time, Ruth and the group hear about the White Rose. A student resistance group in Munich. Thousands of leaflets. Graffiti on the walls: “Down with Hitler! Long live freedom!” Then the arrests. The torture. The executions. At the end of March, a courier brings them two copies of the latest White Rose leaflet6. If this is the legacy of those young people, their duty is to carry it on. One copy reaches Switzerland. One reaches Britain.

“We have found a way to smuggle the leaflet and situation report into Switzerland. And a second way via Sweden to England. It can no longer harm the Scholl siblings if their illegal acts are spread throughout the world. But it is immensely important to us that people outside learn that there are also human beings in Germany. Not just Jew-eaters, Hitler's followers, and Gestapo henchmen. The world knows far too little about this so far.” — 27 March 1943

Ruth’s daughter, Karin, is eighteen. Horrified by the story of Hans and Sophie Scholl, she joins the group.

On September 8, the news spreads: Italy has signed an armistice. Another front. Another battlefield.

"All necessary measures have been taken," reassures our army command. Since yesterday, Germans have been shooting at Italians, and the soil of Italy has once again become a theater of war.” — 10 September 1943

1944: Terror and waiting.

The old year ended in terror. The new one begins in terror. Heavy night raid on December 29th. Heavy night raid on January 1st. The heaviest night raid of this war on January 2nd. We sweep rubble. We nail cardboard. We sit without water, without transportation, without electricity. The telephone is also dead, and only indirectly does one learn whether friends living far away are alive. A promising start to the year.” — January 1944

To resist, in 1944, means to survive. To stay. To rebuild what’s left of home. To live inside the ruins. To convince yourself it is still home. And to wait.

Wait for the end. Wait for the invasion.

The “Uncle Emil” group is well informed. They have sources even within the Army. One of them goes by the name “Hinrichs” — real name: Hans Peters. A lawyer. Now, a Major in the Air Force Command. Always eyed with suspicion by the Nazis, but never caught. A friend. A member of the group. It is he who calls Ruth early one morning.

"Hello! Hello! Is that 727035! One moment, I'll connect you with Major Hinrichs," reports an excited voice on the telephone. I rub the sleep from my eyes. Half past six in the morning. … Then Hinrichs is on the line. "Are you up already?" he asks cheerfully. "Did you sleep well? By the way, what I still wanted to say: the shipment has arrived! Yes indeed! With the first morning train. Pretty good thing, as it seems to me." My brain deciphers at warp speed. The keyword "shipment" means invasion. That is the leap onto the continent. The long-awaited landing of Allied troops.” — 7 June 1944

June 6, 1944. The Allied land in Normandy. The war might really end.

Of course, the Nazi press claims they were expecting it. That counter-plans are ready. But Berlin keeps getting bombed. Every day. By now, even propaganda can’t keep up. Hinrichs thinks the end is near. The resistance feels it too.

“Something is in the air again. But no one dares to say it. That there are numerous groups and small groups that have joined together for active action against the regime is no secret to us. We know that the Communists are working, that the Social Democrats have formed a fighting group, that the Catholics are also not idle, and that in the Abwehr (i.e. the military intelligence) and army command, thoughts of a coup have long been entertained.” — 26 June 1944

Hope grows. But also doubt.

“The dilemma remains the same. Can a small group of ten or twenty determined people bring the Third Reich to falter? And we are just small groups. Small groups in Berlin, small groups in Munich, in Breslau, in Dresden, or Hamburg. A handful here, a handful there, who, like the royal children in the fairy tale, never find each other. Perhaps the generals have greater possibilities for influence!” — 26 June 1944

There is one hope left: that the generals will do what civilians cannot. Eliminate Hitler. End the war. Then comes the news:

”The time has come! And it came much faster than we all thought. No one knows anything more precise yet. Hitler injured... Hitler dead! An assassination attempt on the Führer... Coup, violence... Revolution... Revolution! We are in the middle of it. Drunk with jubilation some, pale with horror others.” — 21 July 1944

But it ends badly. After July 20, anyone could be a suspect. A wrong word. A suspicious look. Ruth is denounced by someone at the newspaper. She is called in by the Gestapo.

“Only with difficulty do I extricate myself from the affair. According to the principle: "Attack is the best defense," I expose the zealous party comrade as a pathetic informer, weave names of high and highest official positions into my speech, juggle with celebrity, Chamber of Literature, complaint to the press office of the Reich government, like Rastelli with his balls, and boast so terribly that the interrogating official becomes increasingly subdued. Finally, he almost apologizes.” — 31 . Juli 1944

But the prisons are full. The Gestapo arrests everyone connected to the failed plot. Some of Uncle Emil’s contacts are captured. Executions follow — public, brutal, filmed for Hitler’s amusement. People Ruth knew. People they admired. Now, dead.

The city turns even darker. Trials are held for show. Sentences are already decided. The goal is terror — and spectacle. Karin, Ruth’s daughter, now part of the group, goes to one of the trials. What she sees horrifies her:

”It's a farce. A rigged affair. Seven defendants. Seven death sentences. The audience sits there as if it were a circus performance. Laughs, shudders, feels a voluptuous tickling in their stomach. And during the break, they chew apples and buttered bread. Fie!"

"When one considers that there are people who go to every session. Like going to the theater or to a crime movie. And that they do it voluntarily. Voluntarily, out of pure fun of the matter..." — 30 November 1944

At one of those trials, Helmuth Graf von Moltke, of the Kreisau Circle, is sentenced to death. He had been close to Ruth. To “Uncle Emil”. They tried to save him — even reached Himmler. It didn’t work. He is executed in January 1945.

This is how the new year begins. With the best people gone. And those still alive — like Andrik, Ruth’s partner — forced into hiding, to avoid being drafted into the Volkssturm. The Volkssturm: a desperate army made up of old men or ill-suited people, now asked to defend a dying city with no hope of winning.

1945

Andrik—Leo—is hidden somewhere in Berlin.

In February, it’s time for their friend Hinrichs, Major Hans Peters, to escape before being discovered. The rhythm of executions is now daily. Life in Berlin has its own rhythm too: hours underground, hours above. Back and forth between cellars and ruins. They learned of the British bombing of Dresden. Ruth writes on February 19th:

"Three times in twenty-four hours, they unloaded hundredweight upon hundredweight of their bombs there. Until hardly a house remained in the entire city. Until all the splendor of a centuries-old culture had perished in smoke and flames. Thousands of people found death, ran like burning torches through the streets, stuck fast in the glowing asphalt, plunged into the floods of the Elbe. Screamed for cooling. Screamed for mercy. — Dying is mercy. Dying is good when one burns like a torch. Dresden was a magnificent city. And it is a little hard to get used to the fact that Dresden no longer exists either." — 19 February 1945

Now, every day brings a new survival mission. Sometimes, unexpected. When Ruth discovers a bombed-out Nazi official's apartment, she seizes her chance — stealing paper, stamps, and Nazi Party seals to forge documents and ration card requests. With these materials, the group secures nine months' worth of ration cards for food, vegetables, tobacco, and milk. Most of these supplies will go to people in hiding — the "submarines" — who are being protected by resistance members throughout the neighborhood.

These are the last weeks before the end. Soviet troops are getting closer. They know who’s coming. They just don’t know yet what to expect.

In the meantime, they keep sabotaging. Cutting cables. Disrupting German Army communications. Helping more U-boats find shelter in hidden rooms, behind false walls.

Then comes the big week. Their most important action. Planned in just a few days. On 16 April, Ruth, Frank (Walter) and Andrik (Leo) meet with the resistance group. They lay a big map of Berlin on the floor. And explain the plan.

"We are planning an action across all of Berlin. For Wednesday night. The first of this scale since 1933. 'No' is the password. 'No' shall cry out to the Nazis from all the walls. With chalk or with paint. With coal or with whitewash. Everyone takes on a specific district." (…) "Thursday we'll meet here at the same time. The painting action will be followed by a leaflet action. On the night of Hitler's birthday." — "I think it will be his last," murmurs Andrik. Everyone smiles. — "Farewell," (…) "And good luck." — 16 April 1945

April 20th. The mission is complete. Across the city, white and red paint spells out the same four letters. Leaflets blanket the streets—messages for Berliners, but also, perhaps, for the soldiers advancing on the capital. Don’t punish us. We are not the enemy. We said NO.

The following day, April 21st, the city goes dark. No running water. No electricity. No telephone lines. The Battle of Berlin is about to begin. And yet, on April 22nd, incredibly, the presses still run. The regime’s newspapers are still hitting the streets with their propaganda:

"The commandment for today, tomorrow, and all coming days is: Without excuses and with utmost passion: Fight." — 22 April 1945

In practice, the city is being ordered to commit suicide. The Gestapo continues to hunt for traitors. They are also on Frank (Walter)'s heels. There is still time to visit friends and make sure they are well... and say goodbye before everyone takes shelter where they can. Frank is now on the run. Ruth and Andrik stay behind. They wait. Until 27 April:

"They're coming!" A man runs towards us. We hear his boots clattering over the pavement. "Russians in the house!" a voice rings out. Andrik and I stand up. Finally! We rush through the long cellar corridor. At the front stair landing, we stop, blinded. The beam of a flashlight is directed at us. Behind it, the world sinks into darkness. "Drusja!" I say into the darkness. "Friends!” Slowly the cone of light lowers. I see a bearded face, two watchful eyes—slanted like Kalmyk eyes—and the high-turned-up collar of a leather coat. The barrel of a submachine gun gleams palely. "Drusja!" The soldier smiles.

Andrik takes over the negotiation. "We are expecting you!" he says in Russian. "We are happy that you are here!" Searchingly, the Red Army soldier looks us in the eyes. "Really?" "Really!" He shines his light into the open cellar doors, shrugs his shoulders, and moves away again. Two others come. Young and tall. They have stars on their shoulder boards and shiny sabers in their fists.

"Well?" one asks. "Do we wear horns? Are we devils?" We shake our heads vehemently. "But you say that we are devils." He taps Andrik's chest with the tip of his saber. "Why do you say such stupid things? Why didn't you do anything against Hitler? Why are you afraid of us?" His face changes, suddenly becoming watchful and tense.”

The afternoon drags on. Evening falls. No Russians. No Germans. It’s as if the group hiding in the cellar has been forgotten by the war. The night is pierced by the crack of sniper fire—lone shooters. A grim legacy of the Reich’s final days, now a threat to everyone.

The night of April 27 unfolds in fear, as they try to flush out the German snipers. To protect themselves—not just from the snipers, but from the Russians’ revenge. But the shots continue. The Russians, forced to clear every apartment, move from door to door. The next morning, they reach Ruth and the others. Everyone is ordered out—hands raised.

“I reach for Andrik's hand. He squeezes my fingers reassuringly. We stand close together in the midst of the onrushing soldiers. Still, shots crack treacherously from the side block. There! Two Red Army soldiers fall headfirst into the sand. Their steel helmets roll like tin cans on the pavement. "We are lost," I stammer. Andrik, too, has turned pale. Large drops of sweat stand on his forehead.”

"You shoot!" the soldier roars and brandishes the submachine gun. In the next instant, we are surrounded. I feel a shove in my back. I stagger forward. Something cold touches my neck. "You shoot!" it cries from all sides. I run. Andrik runs beside me. Suddenly Stolzberg is there too. Three Russians in front of us, three Russians behind us. The muzzles of their submachine guns stare like dead eyes. We are dragged away at a gallop. Our feet run on their own. Run... stumble... run on. A fence rises before us. With one leap we are over. I see bushes, hedges, wooden crosses. The cemetery. A dead man lies across the path. Is he German? Is he Russian?”

The group proceeds, surrounded and pushed forward by the soldiers. Their rifles used to drive them ahead. Down to a cellar, a kind of improvised neighborhood military command post. With a mix of suspicion and curiosity, the commanding officer turns to Andrik.

"Why are you speaking Russian?" — "I was born in Moscow." — "Why do you live here?"— "My parents are German." — "Did you listen to our station?"— "Every morning at eleven." — "When did you last hear it?"— "Last Tuesday, when they broadcast the German news. Then they cut off our electricity." — "What did we say on Tuesday?" — "That there is fighting in Lankwitz and in Friedrichshain, that they are breaking into the city from the south and from the east." The colonel furrows his brow. Like iron masks, the faces of his officers stare.

Andrik straightens up. All the terrors of death have fallen from him. Courage shines from his features—courage and an unwavering confidence. "We hate the Nazis," he says loudly. "For twelve years we have been waiting for you. We have always been on your side."

The soldiers remain suspicious. They decide on a trial by fire:

"Do you know the Russian national anthem?" — "I know it." — "Sing it for us." — Andrik sings, and his calm voice rings through the room: (…) He sings for our lives. We know it. The candles crackle. Otherwise, you hear no sound. (…) Slowly, the expressions of those sitting before us change. From masks they become human. (…) It is quiet in the cellar. The candles smolder, and like thick fog, the smoke of countless cigarettes hangs in the air. The colonel pushes a half-filled glass of tea across the table. "Drink it, Comrade!" Andrik gulps down the tea in one go.”

“As if someone had given them a sign, the officers jump up. They surround us, pat us on the shoulders. They laugh, shake our hands, and talk to us in their foreign, incomprehensible language. Andrik hardly knows whom he should answer first.”

(…) We are offered food: bacon, sausage, groats. "Kushaitye, pozhaluysta." Orderlies run around, bringing fresh tea, sugar, and preserves. Everyone wants to give us something. "You don't have any meat? Here is some. Please, take it. Are you lacking bread? Here it is."

They could all come home now. Free at last, carrying abundant food as if it were Christmas. In the cellar, they shared food, songs, and cigarettes with the Russian soldiers. The war was over.

“The war is over. In this hour, peace begins for us. You are free, Frank Matthis. You are free, Jo Thäler. Free are you all who lived in hiding for years. Wald and Hartmann, Ralph, Rita, Konrad, and you countless thousands who said no to Adolf Hitler's disastrous policies. The great injustice has ceased. We greet you, Helmuth von Moltke! We greet you, the Scholl siblings, you, Ursula Reuber, you, Heinrich Mühsam, you, Peter Tarnowsky, and Wolfgang Kühn! We are beginning. In your name we are beginning!” — 28 April 1945

The final entry in Ruth's diary is dated August 24, 1945:

“Yesterday evening at eleven o'clock, Andrik died. The stray bullet of an American patrol hit him fatally, shortly after he had given his last concert before Allied troops. 'Next time I will play Bach for you,' he said to his English friend. Then the shot rang out. And then he said nothing more. Andrik Krassnow is dead. He was forty-six years old when he had to leave life. And he liked to live.”

Epilogue: A woman and her Legacy.

After the war, Ruth Andreas-Friedrich returned to journalism. She stayed in Berlin for three more years. In the autumn of 1945 she completed the diary from which this story is drawn.

The diary was first published in 1946 in the United States, under the title Berlin Underground. A year later, it appeared in Germany as Der Schattenmann (The Shadow Man), though Ruth had wanted to call it simply “Nein!” — No! Her publisher refused. Every word in that diary was carefully verified. Ruth and the five closest members of her resistance group “Uncle Emil” had to submit a detailed report to the Soviet authorities in 1945, and again in 1946.

Those three postwar years in Berlin became the subject of a second diary, Schauplatz Berlin (Scene: Berlin) — a raw, powerful book about survival in the ruins.

In 1948, Walter Seitz (“Frank”), her co-conspirator in the NEIN action — moved to Munich. Ruth followed him. They married. From there, she continued writing as a freelance journalist.

But Berlin, her city, forgot her. When, in the late 1950s, the city began honoring the “Unsung Heroes” of the resistance, Ruth was ignored. She no longer lived in Berlin. She was no longer considered a Berliner.

Still, she remained committed to reconciliation. In 1959, she joined the board of the German-Israeli Study Group in Munich, working toward dialogue between Jews and Germans.

By then, Germany was basking in the glow of the Wirtschaftswunder, its economic miracle. Resistance — especially civilian, nonviolent resistance — had no place in the national story.

In the West, Ruth’s legacy remained in the shadows. Her books were out of print. Her name nearly forgotten. But something shifted over time. In 1972, Der Schattenmann was published in the GDR. Then came translations — French, Dutch, Hebrew, Hungarian, Japanese, Brazilian Portuguese. A quiet reawakening.

On September 17, 1977, abandoned by her husband, Ruth Andreas-Friedrich took her own life.

It was only in the 1980s, as Germany began shaping its Erinnerungskultur — its culture of remembrance — that Ruth’s voice began to rise again. In May 1985, excerpts from Der Schattenmann and Schauplatz Berlin were read on Berlin radio, and performed in public to mark the 40th anniversary of the capitulation. In 1988, a memorial plaque was installed on the building in Berlin where Ruth had lived — and from which she had organized the Uncle Emil group’s quiet revolt.

In 2002, she was honored by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations. Two years later, her daughter Karin received the same honor. And in 2020, the German historian Wolfgang Benz gave this forgotten group new voice. His book, Protest und Menschlichkeit (Protest and Humanity), tells the story of Ruth, and of around twenty of the bravest, most discreet fighters who made up “Uncle Emil.”

In every generation, there are those who know how to say NO. No to violence. No to tyranny. No to indifference. A few are enough — just a few — to justify, in God’s eyes, the existence of their generation and those that follow. Only thirty-six, says the legend. A few are enough, in the eyes of humanity, to save a country from eternal disgrace — and to make it worthy again of a place in the world.

May the memory of Ruth Andreas-Friedrich be a blessing. And may it give us the courage to say NO when our time comes to choose.

Helmuth James Graf von Moltke (March 11, 1907 - January 23, 1945) was a German lawyer, prominent resistance fighter against National Socialism, and co-founder of the "Kreisau Circle." Moltke rejected a career as a judge early on because he openly criticized the Nazi regime. During World War II, he worked as an expert in international law at the Foreign Intelligence Office of the Wehrmacht High Command, where he advocated for compliance with international law and humane treatment of prisoners of war. From 1940, Moltke organized the Kreisau Circle, a civil resistance group that developed concepts for a democratic and constitutional reorganization of Germany after the Nazi dictatorship. Moltke established contacts with representatives of various social groups, including Christians, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. After his arrest in January 1944, he was sentenced to death and executed on January 23, 1945, in Berlin-Plötzensee.

The instrumentalised "Silent Night" (German), Deutschlandfuk, 2015

The Kreisau Circle was a resistance group that focused on political and social reorganization after the expected collapse of the Nazi regime. Led by Helmuth James Graf von Moltke and Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, the group brought together people from varied backgrounds. Its members steadfastly opposed the Nazi regime while planning extensively for Germany's democratic future. They created detailed blueprints for rebuilding the country after Hitler's removal. Their work ended tragically when, following the failed assassination attempt on Hitler, many members were arrested and sentenced—some to death by hanging. See also: “The Kreisau Circle’s “Declaration of Principles”, issued on August 9, 1943.

Samson "Cioma" Schönhaus (1922-2015) was a German graphic artist and writer who lived illegally as a Jew in hiding in Berlin during World War II. As a skilled forger, he created hundreds of identity documents that helped other Jews survive. Working closely with members of the Confessing Church, including Franz Kaufmann and Helene Jacobs, he managed to save many lives. In 1943, he made a daring escape from Berlin to Switzerland by bicycle, using a military identity card he had forged himself. His memoir, "The Forger" (originally published in German as "Der Passfälscher" in 2004, English translation 2007), and the 2022 feature film "Der Passfälscher" (The Passport Forger) tell his remarkable story.

Fabrikaktion ('Factory Action') was the final major roundup of Jews in Berlin, lasting from February 27 to early March 1943. Most victims were factory workers or employees of Jewish welfare organizations. Though this Nazi operation occurred across Germany, it became historically significant for triggering the Rosenstrasse protest - the only mass public demonstration by German citizens against the deportation of Jews.

The White Rose's sixth and final leaflet proved fatal: Hans and Sophie Scholl were caught distributing its 3,000 copies at Munich University on February 18, 1943. In autumn 1943, the leaflet was reprinted in England, then dropped over Germany by British planes and broadcast by the BBC. The full text here.

Share this post