How can people survive being locked in underground cellars for over a year? How did they endure hiding in Kyiv's sewers or Poland's forests? How can anyone survive in a cave with no sunlight for more than a year? How can hostages survive being held in the tunnels of Gaza? What enabled some people to survive the Nazi extermination camps?

In 1946, Viktor Frankl, a Viennese psychologist who survived four concentration camps, wrestled with these questions as he processed his memories. Through his harrowing experience at Auschwitz, Frankl discovered something crucial: survival depended on having a purpose, an ideal, a reason to live. A meaning.

Based on this insight, Frankl developed logotherapy—a psychological therapy focused on finding meaning—and authored numerous books that are now essential reading for those exploring these profound questions.

These questions continue to challenge us today, as humans still face such extreme experiences, despite our hopes that they would never recur. Through it all, humans must find their reasons to survive.

Last summer, while reading a book by the Polish Nobel Prize-winning author Olga Tokarczuk, I discovered a reference to the caves of western Ukraine - formerly Polish and Austrian territory - which are among the largest in the world. Following a Wikipedia footnote and a series of links, I stumbled upon an extraordinary story of survival: between 1942 and 1944, a group of Jewish families took refuge in these caves, hiding in extreme conditions for more than a year while waiting for the war to end.

Although the story haunted me, I put it aside - until August, when I visited the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt am Main. There was a travelling exhibition called "Hideouts: Architecture of Survival" , which had made a stop there. The exhibition used casts to document the most unlikely places where Jews managed to survive during the Second World War in Poland and Ukraine. Among them was a cast of the very cave that had so fascinated me: a millstone used to grind flour for baking bread underground.

Coincidences don't exist - resonances do. When a story that was completely unknown to me before appears twice in the space of a few weeks through such different channels, it demands to be told again.

So today I'm telling this story of extreme survival, drawing carefully from sources I cite in this post. It's a story of meaning, of struggle, and of the love of family. It's a Jewish story. It's a European story.

Small Villages and Big Caves: Between Ternopil and Chernivtsi

The caves of the Ternopil region are well known among speleology enthusiasts: they include some of the most extensive underground systems in the world, such as the Priest's Grotto, in Ukrainian Озерна (Ozserna), or Blue Lakes Cave, which extends over 140 kilometres of explored passages, making it the 16th longest cave system in the world. Following Ukrainian independence, a tourist movement has developed around these caves, along with speleological and archaeological studies, and a number of specialised local tour operators. Don't expect the guides to give a full account of what happened in the area between 1942 and 1944, especially the story of the Jews in the caves: this part of history is little more than a footnote.

In the heart of this rural area, where Galicia, Podolia and Bukovina converge, small villages still dot the landscape. Among them, Korolivka was a vibrant centre of Jewish life: before the Second World War, it was home to some 500 Jewish families, making up about 40 per cent of the total population. The town boasted two synagogues and a cemetery, which served not only the local Jewish community but also those from the surrounding area.

Life was relatively good in the region in the late 1930s. Esther and her husband Shabsy Stermer (known to everyone as Zeida) were considered happy - they had a large family of six children and grandchildren, lived in a large house, and Shabsy was a successful merchant. In the nearby village of Bil'che-Zolote, Esther's sister Leiche Wexler also enjoyed a comfortable life with her merchant husband and their two children.

Esther emerges as the heroic figure at the centre of this story of survival. She spoke German, listened to the radio and understood world events. By 1939, she and her husband could see the darkening situation clearly.

The Stermer family had secured papers and planned their escape to Canada, with passage by boat from Poland scheduled for September 8, 1939. But Hitler's invasion of Poland the week before, followed weeks later by the Soviet occupation of western Ukraine, left them trapped.

Sol Wexler, the son of Esther's sister, secured new documents for their planned escape to the United States, this time via Russia and Japan. But when Germany broke the non-aggression pact and invaded Russia in 1941, taking control of most of the Ukraine, these plans collapsed. The region where the Stermer family lived was in the path of Hitler's march to Stalingrad.

"We felt the black clouds blowing our way"

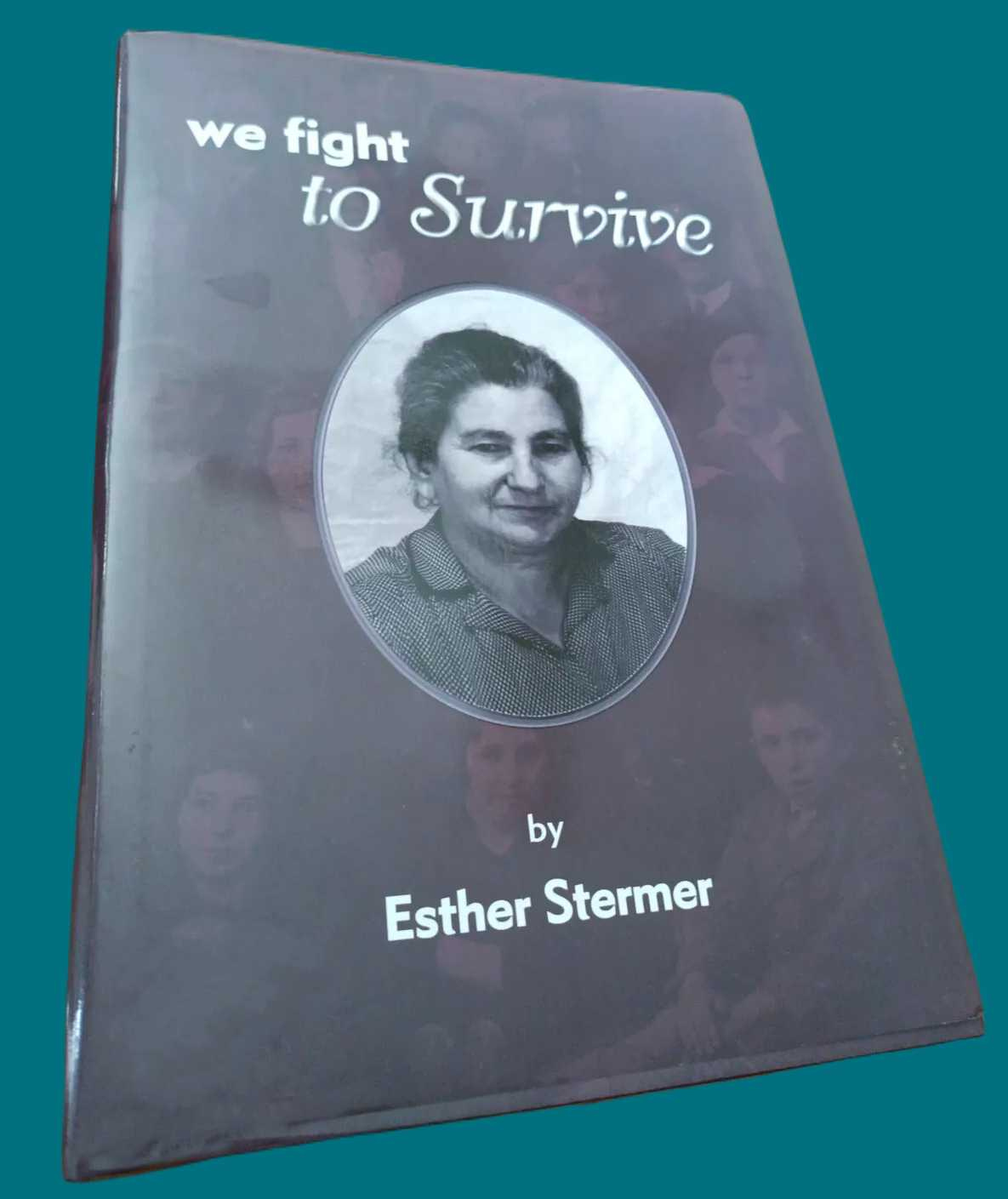

Esther wrote in her memoirs - a story she wrote in Yiddish in 1960 and later translated into English.

As the Germans began to create ghettos, Jewish families built hidden bunkers under their homes. The Stermers, who adamantly refused to move to the ghetto, used these hiding places to avoid capture.

The situation became even more dire when the Nazis began their "Aktion" operations, in which they tricked Jews into gathering, only to deport them to death camps or execute them on the spot. As reports of mass executions continued to mount, the Stermer family faced a grim realization: no one would survive unless they took drastic action. In her memoir, Esther wrote:

"The world had turned animal—or worse. Every day conditions became worse. Death stalked each step... But we were not surrendering to this fate. Our family in particular would not let the Germans have their way easily. We had vigor, ingenuity, and determination to survive. Above all, our family would stand together... But where could we go? Clearly, there was no place for us on earth."

Esther's eldest son, Nissen, Esther's husband, Shabsy, and their son-in-law, Fishel, were among the few Jews still allowed by the local police to work as junk collectors, travelling by horse and cart through the surrounding villages. This gave Esther the opportunity to give Nissen the most important task of his life: to find every possible hiding place for her extended family. A doctor friend in the village of Bil'che-Zolote suggested they check the Verteba cave near his home.

On a frosty October night in 1942, Esther's extended family and the doctor's family ventured into the cave after loading their remaining possessions and supplies onto Nissen's wagon. To enter the cave, the fugitives had to slide backwards through its narrow mouth. At first they used ropes to navigate the vast system of tunnels and avoid getting lost, but gradually they learned their way around. To create a semblance of home, they made wooden beds and tables. They relied on candles and small bottles of kerosene for lighting. They adapted to a nocturnal existence - sleeping during the day and being active at night. Three men maintained their vital supply lines: Esther's husband Zeida, his son Nissel and his son-in-law Fishel, who carried sacks of the essentials - flour, potatoes, kerosene and water.

Esther wrote:

'Nissel was our most important contact with the outside world. […] Every trip made outside was an odyssey more hazardous than anything the Greeks ever dreamed of in their nightmares... Those who have been spared our tribulations can hardly imagine how much courage, ingenuity, strength, and determination his daily activities called for.'

Despite the physical protection offered by the cave, Verteba was only a temporary refuge. The cave was well known and had even been a local tourist destination before the war. What if Ukrainians decided to visit the cave after the winter?

Water became their most pressing concern. They found places where water dripped from stalactites and cave walls and collected it in small bottles and pots, but the meagre supply was never enough.

By the end of the winter of 1943, the families had retreated deeper into the cave and began searching for a second secret exit - a precaution against being trapped by the Gestapo. Esther's three sons - Shulim, Shlomo and Nissel - discovered a small crack in the ceiling of a nearby passageway. After four weeks of determined digging, they broke through to the surface, creating a secret escape route that would prove crucial to their survival.

One day in 1943, as the snow was melting, someone - German or Ukrainian - noticed potatoes near the cave entrance, probably dropped during nightly supply runs. The Gestapo was informed and on April 5, 1943 they stormed the cave. Most of the 28 people managed to escape into the darkness, but eight, including Esther, were captured. Esther stood face to face with the Nazi commandant and began to speak German:

“Very well, so you have found us. What do you think? Do you think that unless you kill us, the Führer will lose the war? Look at how we live here, like rats. All we want is to live, to survive the war years. Leave us here.”

Did Esther really believe they would be released? Of course not. But she bought time for the others to hide, as the rest of her children and fellow survivors crawled deeper into the dark maze of underground tunnels.

After her exchange with the commandant, eight Jews were taken prisoner and marched at gunpoint toward the cave's entrance. Miraculously, three of them—including Esther and her son Shlomo—managed to escape into the darkness before the soldiers could fire their weapons. Five people remained in Gestapo custody, including Esther's sister Leiche and her little son Leo.

The remaining Jews made for the second exit and fled in different directions into the cold. When the Gestapo sent the local police back to look for more, all they found were the possessions that the cavers had left behind.

The five Jews captured by the Gestapo were handed over to the local police for execution. Three would eventually survive because Esther offered the Ukrainian police chief money to release the prisoners.

The chief devised a plan: five bodies would be exhumed from the Jewish cemetery in Bil'che-Zolote before the scheduled execution. At dawn, the prisoners would be taken to the cemetery, where the executioner would fire into the air, allowing them to escape. If the Gestapo demanded proof, they would have bodies to show. But the police chief realised that Leiche, Esther's sister, was from the village of Bil'che-Zolote. Fearing that she might later testify against him, he killed both Leiche and her son, while letting the other three go free.

A New Cave, Another Winter

Desperate to find a permanent refuge, Nissel followed the advice of a Ukrainian friend - one of the few allies of the Jews at the time - and went to a place called Popowa Yama - the “Priest's Grotto”, now known as the Ozerna (Lake) Cave, less than four kilometres from the village of KorolÍvka and virtually unknown.

The cave had only one small opening and had to be entered feet first. It was completely dark inside, but by the weak light of his candle he could see that he was in a small room surrounded by large boulders. Most importantly, they found underground fresh water lakes and no signs of human habitation.

This was the place.

On the night of May 5, 1943, Esther and Zeida Stermer, their six children, four other relatives and twenty-six other Jews gathered their remaining supplies and fled to Popowa Yama. In total, 38 people. One by one, in complete silence, they descended into the pit. At the bottom, a terrible darkness poured out of the narrow entrance, causing the youngest children to cry. For many of them, this would be their last glimpse of the sky for almost a year.

The survivors chose a series of four interconnected rooms for their new home. The rooms were larger and naturally ventilated. The families designated areas for sleeping and set up a cooking area near the water.

Their next challenge was to establish reliable supply lines. With only two weeks' worth of kerosene, flour, matches and other essentials left - and no way of knowing how long the war would last - they needed to stockpile resources. Without local work permits, every trip outside for supplies became a life-or-death mission. After two weeks, the men made their first venture out to cut wood for their new home. Although they worked in the dark, they were terrified by even the slightest sounds in the forest. Their second mission was to gather cooking oil, detergent, matches and flour. These dangerous expeditions left them so exhausted that they slept for twenty hours afterwards.

This extended sleep pattern became their new circadian rhythm as the families entered a state of near hibernation. Without the distinction between day and night, their biological rhythms adapted to survival. They slept eighteen to twenty-two hours at a time on hard wooden planks, waking only to eat, relieve themselves and attend to basic needs.

Patiently, the survivors turned the cave into a long-term shelter. They dug trenches for upright walking and built stone walls to conserve body heat and block draughts. The stone walls are still there: carefully levelled with stones at their base.

Living mostly in darkness to conserve their precious candles, the Stermer family developed a clear leadership structure. Authority flowed naturally from Esther and her husband Zeida to their eldest sons, with each family member assuming specific responsibilities.

Esther wrote:

"Inside our cave, each one of us had specific duties," […] "We cooked, we washed, we made needed repairs. Cleanliness was absolutely essential. Life in our grotto developed its own kind of normalcy."

The Stermer brothers even stole a 150-pound millstone and miraculously managed to bring it into the cave to grind grain into flour. They used it primarily to make Mămăligă, a polenta made from yellow maize flour.

Among Esther's responsibilities was tracking the moon's phases, which proved vital not only for their nighttime supply missions but also for maintaining their calendar. This enabled them to know the precise date to observe Yom Kippur in 1943. Esther recalled:

"We had a prayer book for the High Holidays. My son-in-law Fishel conducted the services. On the day of Yom Kippur, we fasted and prayed."

The Neighbors Became Enemies

The worst moment of this underground life came one evening when one of the fugitives discovered that the entrance to the cave was completely blocked.

A wall of earth and rock had sealed them in. Later, the survivors learned that a group of Ukrainian villagers had filled the ravine with rocks and earth to seal off the entrance to the cave. Their aim? To kill the Jews who were stealing their potatoes and grain.

It took them three nights to reopen the main entrance a few metres away, but it was clear that finding a second secret exit was now a matter of life and death. And it was also clear that from that moment on any mission outside would be even more dangerous than before: were the Nazis or the local Ukrainian police watching the main entrance? Or did they think those Jews might already be dead?

For weeks they had been looking for suitable places to dig up and create a new exit, but every attempt failed and the risk of being buried by the rocks had become extremely high.

Endurance and Hope

During the summer months, when Ukrainian farmers filled the fields, they made dangerous missions to find food and, as autumn approached, to stockpile fuel, tools and blankets.

Their diet was reduced to bare survival: just grain and sliced potatoes. As winter approached, they faced another threat - lack of water. The level of the underground lake was dropping rapidly, and soon the surface water would freeze. Would all their efforts end in starvation?

The last two weeks of October became the ultimate test of endurance. Nissen and the others knew this was their last chance to gather winter supplies, as freshly harvested potatoes lay in piles in the fields. Under cover of darkness, they managed to get a few sacks of beans and potatoes back to Popowa Yama.

The goal was to gather enough food so that they could hide underground for months and wait. One last mission was needed. What they didn't know was that the local Ukrainian police were watching the hole from the nearby woods - waiting.

On the 10th of November, when they returned from this last mission and entered the cave, gunfire erupted and bullets flew. Miraculously, they were able to take cover behind the boulders used to block the entrance, slip into the cave and seal it. No one came after them. When December arrived and everything above was frozen, no one looked for them again.

Cut off entirely from the outside world, the families established a carefully structured daily routine for survival.

"We were continuing our routine in the cave. Washing, grinding flour, and preparing our meager meals. We would chop up the wood in small pieces and divide them among our people, making sure that no one used more than they had to."

"...Our passion to see the complete destruction of the Germans impelled us to these efforts. We told each other that God had Himself created this grotto for us, so that we might live to see the redemptive day of Hitler's downfall."

As winter turned to spring in 1944, some of the Stermers ventured out to meet their village friend, who told them that the German front was collapsing. Russian troops were approaching - the echo of their machine-gun fire and bombs could be heard in the distance.

But prudence told them to stay in the cave. The front line swept back and forth over the mouth of the cave in a steady exchange of artillery and small-arms fire. There was no telling when it would be safe to emerge. Their fears grew: would they survive to emerge from the darkness into a liberated land?

'Our joy was great, but there was also anxiety whether help would reach us, or whether ours would be like the story of Moses, who saw the Promised Land from the distance but was not privileged to set foot on it. Might not the same happen to us?'

One morning in early April, Shlomo approached the bottom of the entrance and discovered a small bottle in the mud. Inside was a message from their friend Munko, which simply read: "The Germans are already gone.”

On 12 April 1944, one by one, the Stermers and their extended family emerged from the cave. The fields were a muddy mess from the melting snow. But the sky was beautiful. There was sun. Too much light for their eyes, which had forgotten.

On the surface, the little granddaughter Pepkala Blitzer, 4 years old, was so frightened that she asked her mother to put out the candle because it was too bright. She had completely forgotten what the sun was.

In her memoir, Esther wrote:

"For years, daylight had frightened us […] It was only at night and in the dark that we had felt secure. For years we had hidden in bunkers, caves, and other dark places, and had been afraid to be seen in God's world. Now we were all able to walk in the middle of the day outdoors... Salvation had come."

Struggling to recognise themselves - their skin yellowed, their bodies covered in mud and malnourished - they made their way to Korolivka. The village was beyond description, reduced to rubble. Those who saw them arrive thought they were ghosts, for they knew that no Jews had survived there. They were almost right: of the more than fourteen thousand Jews who had lived in the region before the Second World War, only three hundred remained alive.

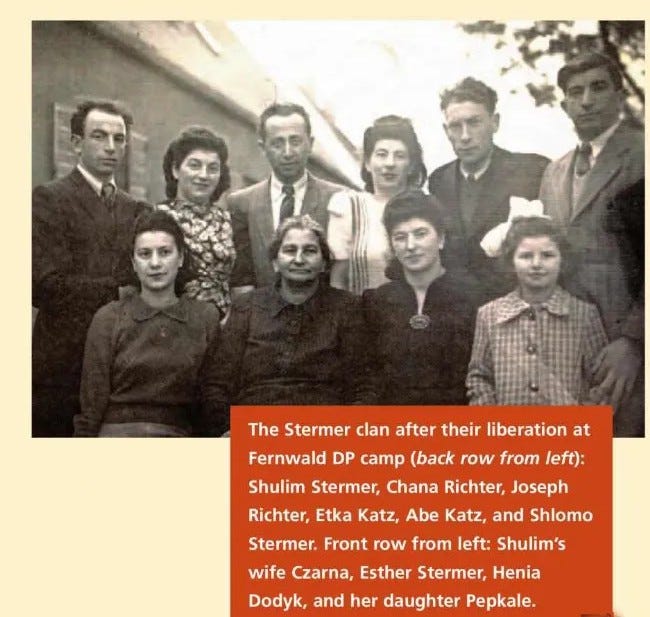

After the war, when Jews were allowed to resettle in Poland, the Stermers and their extended family seized the opportunity. But they didn't stay there for long. From Poland they made their way to Germany, where they lived in displaced persons camps until the end of 1949. Eventually, they set sail for North America, where Canada and the United States became their new homes and a new beginning.

"We were masters of our own fate in the cave" […] "There was no one to whom we owed our safety or upon whom we depended. After our men came in from the outside and scraped off the mud which would cling to their clothing at the entrance, and they had washed, they were free men."

Conclusion

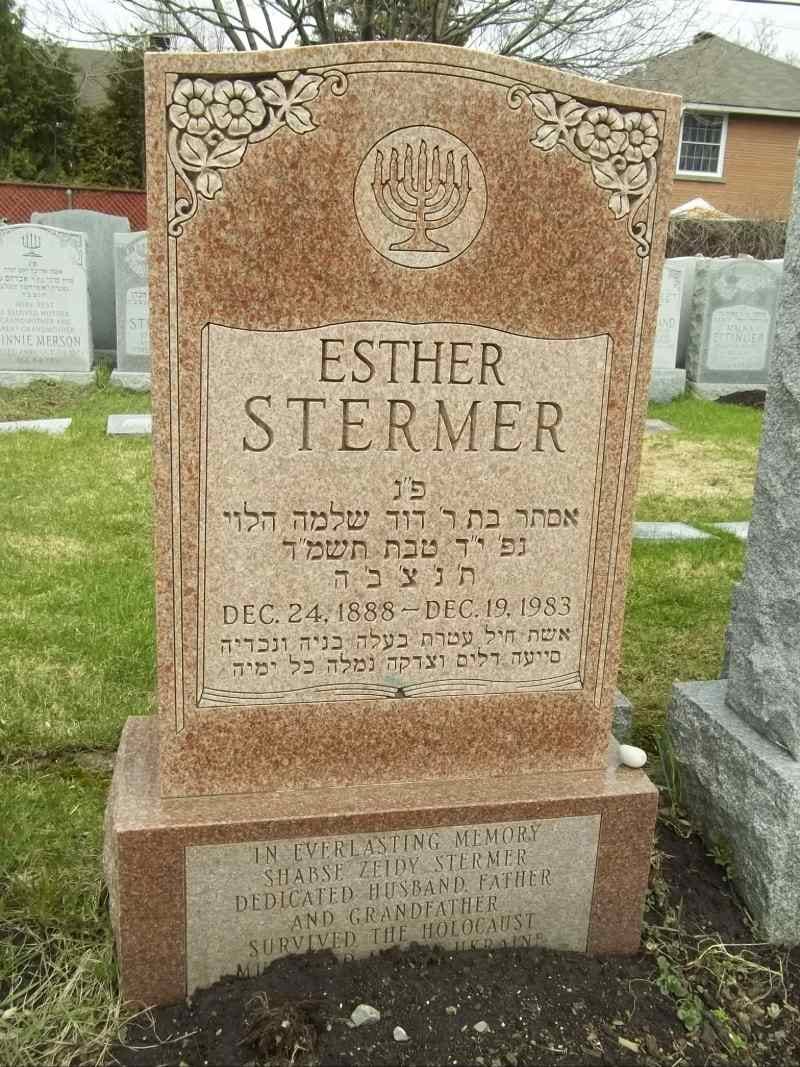

What drove our protagonist Esther? Her purpose was family—not merely surviving for herself, but keeping everyone together and securing their future.

"A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life," writes Viktor Frankl in Man's Search for Meaning

Driven by love for her family, matriarch Esther emerged as a biblical heroine—a modern-day Noah with the cave as her ark, and like Moses, she led her people to their promised land: a new life for her family. Even in darkness, Esther and her clan never stopped imagining—and striving for—the future.

"Even in the most difficult moments of existence, man can find meaning by looking to the future." Ibidem

This is how people survive in caves, tunnels, prisons, and concentration camps.

Esther Stermer´s memoir

Esther died in 1983, aged 95, leaving 125 children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Epilogue: How This Story Reached Us

The stories of the survivors remained largely unknown for decades. Esther Stermer wrote a Yiddish memoir in 1960, which was later translated into English. Sol Wexler, Esther's nephew, documented his experiences through the UN Relief Administration, while other survivors contributed to Spielberg's Visual History Archive.

In the 1960s, a Ukrainian boy discovered evidence of war refugees in the Verteba cave - shoes, bottles and mysterious wall writings. He grew up to become museum director Mykhailo Sokhatskyi, but his research hit a dead end.

In 1993, American speleologist Christos Nicola found similar artefacts in the Priest's Grotto cave. After nine years of research, he received a breakthrough email from Sol Wexler's family. This led him to the Stermers and other survivors who lived in these caves.

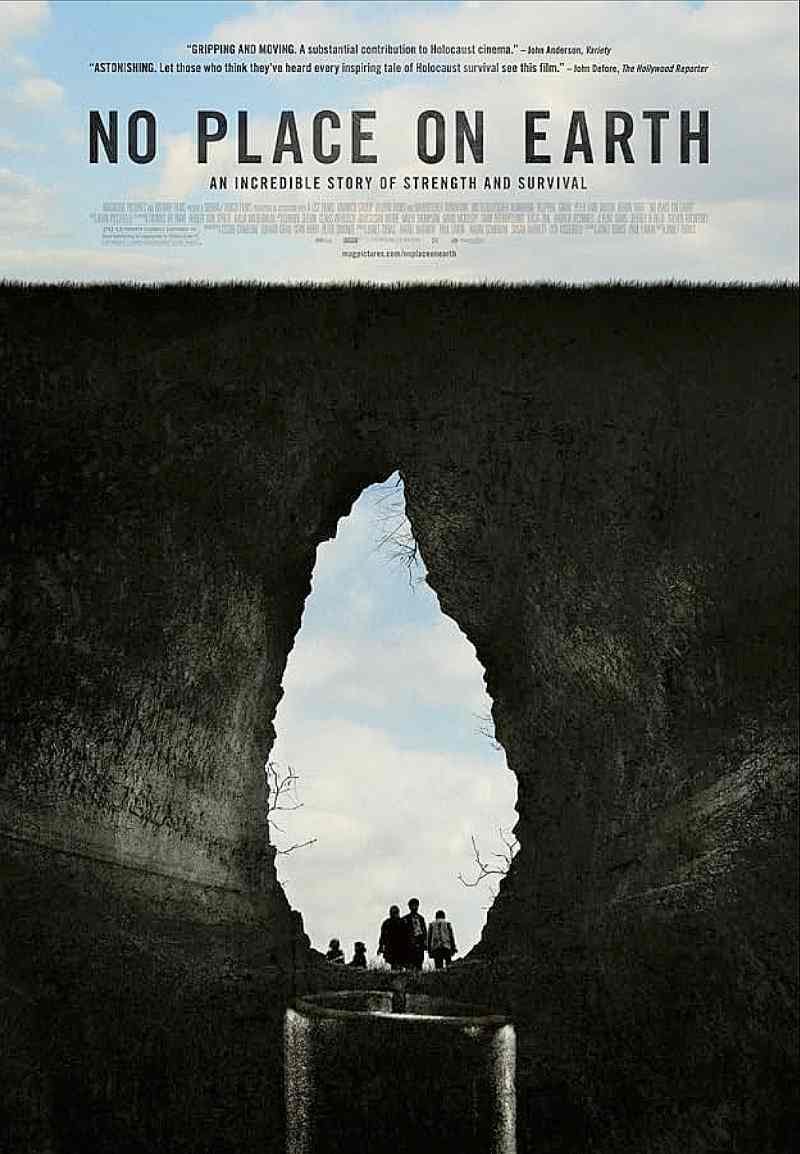

The story was featured in National Geographic Adventure in 2004 and inspired both a young adult book, The Secret of Priest's Grotto (2007), and a 2013 documentary featuring Nicola and four survivors. Here:

The movie

Released in 2012, is available on Amazon Prime and on Youtube

Sources online

Christos Nicola, Peter Lane Taylor, The Secret of Priest's Grotto: A Holocaust Survival Story, 2007

Europe Between East And West, blog: Caving In – Optymistychna: The Ukrainian Underworld, 2021

Відвідай туроператор (Vidvidai Tour Operator): 5 the Most Interesting Caves in Ternopil Region

Smow Journal, Natalia Romik. Hideouts. Architecture of Survival at the Jewish Museum, Frankfurt, 2024 / also in the Frankfurt Jewish Museum website

Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine, Media Portal, 11 min. documentary on the Ozernaya Cave, 2011

National Geographic Magazine, The Darkest Days, July 2004, via WebArchive.org

Haaretz, How Caves That Have Sheltered People for 6,000 Years Saved Jews From the Holocaust, Jul 22, 2023

Mykhailo P. Sokhatskyi’s scientific contributions on Research Gate focused on the prehistoric history of Verteba and Priest´s Grotto

(Video) Hideouts. The Architecture of Survival. - lecture by Natalia Romik at the Art Biennale Budapest, Nov 2024

Share this post