Dresden: Memory, Hijacked.

Every year on 13 February, the anniversary of the 1945 bombing, Dresden becomes a flashpoint as right-wing and neo-Nazi groups march through the city. Far-left counter-protesters confront them, sometimes leading to street clashes. Between these opposing groups, ordinary citizens form human chains to protect the dignity of their city. The eightieth anniversary of the bombing in 2025 was no different:

Dresden is probably the most beautiful city in Germany: rich in culture, innovative and pleasant. Yet, it also mirrors the contradictions and ambiguity in German memory culture.

For years, a dominant narrative portrayed the bombing of Dresden as an unnecessary act of destruction and a war crime1. Historians have clarified since a long time that Dresden was a legitimate military target, though what happened there remains a tragic story. Any sensible person would draw just one lesson from it: the rejection of warmongering. But even well-researched history books struggle to counter the effects of post-war narratives that emerged to serve political agendas — especially in East Germany, but not only.

It's not just about Dresden. As I showed in the previous post with some data, there is a collective memory - and yes, there definitely is one - but it's dotted with gaps and shadows.

In these shadows, certain attitudes and ideas have persisted; in the voids, new narratives have emerged. The result is a culture of remembrance that leaves us uncertain whether it represents a great German success or a great self-deception.

This uncertainty extends far beyond Germany's borders. In 2019, Berlin-based American philosopher Susan Neiman urged Americans to follow Germany's example in confronting their legacy of slavery and racism (Learning from the Germans, 2019). However, by October 2023, after observing how Erinnerungskultur had evolved into a form of ongoing censorship that diminished cultural life, Neiman reversed her position with an editorial titled Historical Reckoning Gone Haywire.

Makes you scratch your head, doesn't it? But if we look at how the culture of remembrance came to be, we find a more nuanced story. One that defies easy summary: not linear, not unidirectional, and full of bumps along the way.

In this mini-essay - the second of a three-part series- (mini-essay… but looong post), I will guide you through the history of German memory culture in the years between 1945 and 1989. I must simplify - this text is intended for those less familiar with the country's history as well - while always maintaining respect for the facts.

1945-1949: The Great Silence.

1950–1967: Coming to Terms with the Past or Drawing a Line Under It?

1968-1970: We Need to Talk!

1970-1978: Filming Between Memory and Propaganda.

1979: "Holocaust" and a Nation's Catharsis.

1980–1989: Foreign Policy Challenges, Social Tensions, and Historical Debates.

“1990 to today: United and Confused” will the third post of this series, soon online.

1945-1949: The Great Silence.

When the Iron Curtain fell in 1945, dividing two Germanys and two Europes, a profound silence also fell. In West Germany, as the nation's crimes became undeniable to the world and to Germans themselves - see the Nuremberg trials - the resumption of daily life seemed almost impossible. Yet there was a country to rebuild from the ruins, and urgently so. Looking forward seemed preferable to confronting the past.2

The urgent need for civil servants, employees, mayors and administrators made it impossible to avoid the reintegration of former NSDAP members - including some war criminals. This situation demanded silence: no talking, no questioning, no writing. A process of normalisation took hold, based on the simple logic of moving forward and leaving the past behind. The West soon abandoned serious denazification efforts in favour of collective reeducation programmes run by the Allied Forces.

Reeducation through the media: memory, imposed.

The Allies used the media to emphasise the moral responsibility of all Germans for Nazi crimes. This was done through newspapers, radio broadcasts and visual communication. The American and British administrations displayed posters in public places showing photos of concentration camps with the headline:

"Diese Schandtaten: Eure Schuld!"

"These Atrocities: Your Guilt!"

At the time, no medium was as powerful as film. Using more than 37 hours of footage shot by the US and British armies at Dachau and other concentration camps, the occupation authorities produced a 22-minute film that was required viewing for the local population in West Germany and Austria: The Death Mills (Die Todesmühlen, 1945) contains most of the horrific images that became the mass media reference for documenting the Holocaust worldwide.

The film provoked a defensive reaction characterized by responsibility denial, claims of victimhood ("what about us?"), and even resentment.

Resentment, then as now, easily shifts the perspective on who are the victims and who the perpetrators. Plus, it ignited a growing fear of retribution and the emergence of secondary anti-Semitism. This fear has been described by historian Frank Biess as one of the defining emotions of early post-war Germany3).

This fear stemmed from concerns that the Allied occupiers and Nazi victims—including former slave laborers from Eastern Europe and Jewish displaced persons still present on German streets—would inflict upon Germans what Germans had inflicted upon others, which was, paradoxically, an indirect admission of guilt. To suppress this guilt, Germans developed a sense of collective victimhood to replace their collective guilt, often imagining themselves in the place of Jewish victims. Yet simultaneously, they blamed these same victims for Germans' current suffering.

This gave rise to "secondary anti-Semitism"4, a new form of Jew-hatred characterised by an inversion of victims and perpetrators: Germans began to see themselves as the true victims of the war, while Jews were portrayed as powerful and vengeful –shadowy manipulators who controlled the media and public opinion about the Holocaust, profiteers who exploited the memory of the Holocaust for material gain.

In these circumstances, it was difficult to expect anyone to break the silence and speak out on behalf of the German people about Nazi crimes. Only one organisation stepped forward in October 1945: the Council of German Protestant Churches.

Breaking the Silence: The 1945 "Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt".

In October 1945, the newly formed Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD), in coordination with the World Ecumenical Council, decided to issue a "Declaration of Guilt" as a public act of contrition:

With great pain we say: Through us, infinite suffering has been brought upon many peoples and countries. What we have often testified to in our communities, we now speak in the name of the whole Church: While we fought for many years in the name of Jesus Christ against the spirit that found its terrible expression in the National Socialist regime of violence; we accuse ourselves of not having confessed more courageously, not having prayed more faithfully, not having believed more joyfully, and not having loved more ardently.5

The German public reacted with widespread outrage, viewing the declaration as a treacherous submission to the victors' attack on German dignity—yet another attempt to impose collective guilt on the German people. Soon there were calls to "draw a final line”.

The Great Reframing in Occupied East Germany.

Unlike the West's approach, denazification in the Soviet zone served as a crucial tool for shaping the new socialist society and was implemented swiftly.

Thousands of judges, teachers, officials, and others in positions of responsibility—not necessarily committed Nazis—were dismissed or had their property seized. This also applied to large landowners, many of whom had been Nazi supporters. This massive "cleansing"—more than 120,000 people were interned—and the replacement of the political elite made it possible to draw a line under the past: according to the Eastern narrative, National Socialism had been eradicated once and for all, eliminating any need for further discussion.6

Instead, the burden of the past was placed entirely on Western shoulders. GDR doctrine interpreted Nazi crimes primarily as a class struggle against communists and socialists. Since fascism was seen as the most advanced stage of capitalism, West Germany - being capitalist - was seen as inherently fascist. Simple, isn't it?

The Challenge of Refugees.

Another major challenge emerged: the millions of German displaced persons in postwar Germany. By 1950, there were 8 million refugees in the Federal Republic and 4 million in the GDR. Like many aspects of postwar history, this chapter would have required significant processing in collective memory—a process that would take decades to unfold. We'll pause this story for now and return to it in the next post.

1950–1967: Coming to Terms with the Past or Drawing a Line Under It?

The society of the 1950s and early 1960s was marked by what was then called "coming to terms with the past" —Vergangenheitsbewältigung— but is now understood as a policy of drawing a line under it —Schlussstrich.

From a German perspective, the past during this period was synonymous with guilt—a burden that had to be addressed through various measures like reparations, diplomatic relations with Israel, and other initiatives, all in the hope of either eliminating or leaving behind this guilt.

"Forgetting" was viewed as a constructive way to focus on the future and pursue renewal. The newly established Federal Republic first needed to reintegrate into the international community, and this required bold, pragmatic, visible gestures.

A pivotal moment came with the 1952 Luxembourg Agreement, in which the Adenauer government committed to paying 3.5 billion Deutsche Marks in reparations to the Jewish Claims Conference and the State of Israel—a crucial step toward ending the Allied occupation statute.

Through today's lens, this was essentially a win-win commercial agreement. The Federal Republic desperately sought recognition from Western nations, while the young State of Israel needed funds for its struggling economy.7

The two parties even framed it differently to the world—Israel called them "payments" while Germany termed them "reparations." Though this arrangement impressed international audiences, other Nazi regime victims, particularly those from Eastern and Southeastern Europe, were left empty-handed. Many Jewish and non-Jewish refugees unconnected to the Claims Conference also saw their claims go unrecognized (with some still pursuing legal action against Germany to this day).

Public reaction was revealing: a poll conducted shortly after the agreement was announced showed that 44 per cent of West Germans opposed it, with only 11 per cent in favour. In Israel, Holocaust survivors protested against the negotiations, denouncing the agreement as "blood money". The debate in the Knesset in January 1952 turned violent, with demonstrators throwing stones outside the parliament8.

On a different note. Germany's surprise victory at the 1954 World Cup in Berne marked another decisive step in the country's return to the world stage. Coming just ten years after Germany had been excluded from all sporting competitions, this forward-looking triumph - which I touched on during last year's European Football Championship - was seen by many as the "real founding date" of the Federal Republic of Germany.

West Germany Starts Investigating Nazi Crimes.

After gaining full sovereignty in 1955, West Germany entered NATO (1955) and the European Community. This Western orientation was reinforced by a widespread popular rejection of militarism.

Internally, the quiet reintegration of heavily implicated Nazis continued. A significant change came in 1958 with the establishment of the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations in Ludwigsburg, which unified the prosecution, investigation, and public documentation of Nazi crimes. However, the federal government countered this initiative by distancing ordinary Germans from collective responsibility and promoting the narrative "not all Germans were Nazis" both domestically and internationally.9

East Germany Celebrates its Anti-fascist Struggle.

In response to West Germany joining NATO, the Warsaw Pact was formed. The GDR then crafted its historical narrative around the "anti-fascist struggle," asserting that anti-fascists and Soviets had defeated Hitler to establish a new Germany—portraying Nazi victims primarily as communist fighters. To promote this narrative, the GDR launched an extensive memorial construction program, with Buchenwald —dubbed the "Red Olympus"— becoming the SED's showcase of communist resistance.

When visiting Buchenwald today, tour guides usually make no mention of Ernst Thälmann, Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Germany and a key figure in the Weimar Republic, who was murdered here in 1944. During the GDR era, paying homage to his plaque was a must and took precedence over commemorating the camp's other non-communist victims: political dissidents, Jehovah's Witnesses, Sinti and Roma, military deserters and, of course, Jews.

East Germany and its Relationship with Jewish Victims.

Initially, there was a strong commitment to preserving Jewish memory, largely driven by many Jewish survivors who returned to the East to help build the new socialist state. However, as in other Soviet-controlled countries—Hungary, Poland, and others—new waves of antisemitism emerged. East Germany's relationship with its Jewish community deteriorated, and by 1953, half of the East German Jews had left the country.

The remaining Jews were accepted only if they contributed to building the "better state." Their contributions were indeed significant: Jewish intellectuals preserved Holocaust memory through literature, art, and documentation—something entirely absent in West Germany at the time. Despite operating under limitations and censorship, this enabled the GDR to claim moral superiority over West Germany, which East Germany denounced as a capitalistic, therefore fascist, state that was appointing Nazis to their highest ranks.

The "Better State" against the "Still-Nazi" West Germany.

In the early 1960s, the GDR launched a propaganda campaign against former Nazis in West Germany through trials in absentia.

In 1960, they convicted Theodor Oberländer - who had joined the Adenauer government as Minister for Refugees and Expellees in 1953, despite a Nazi past that included participation in the Lviv massacre.

In 1963, a similar trial targeted Hans Globke, one of the authors of the 1935 Nuremberg Race Laws, who became Adenauer's chief of staff in 1953 and was one of the most influential figures in West Germany.

In 1964, the East German Stasi waged also a campaign against CDU member and Federal President Heinrich Lübke, accusing him of having overseen the construction of forced labour camps during his time as an architect in Nazi Germany. The controversy damaged Lübke's reputation and, together with his failing health, contributed to his resignation from the Federal Presidency in 1969.

They even targeted the leader of the Social Democratic Party, Kurt Schumacher, who was actually a resistance fighter against the Nazis, arrested in July 1933 and forced to spend ten years in concentration camps.

Germans Facing The Big Trials.

The 1960s began with two pivotal events: the Eichmann Trial (1961) in Jerusalem and the Auschwitz Trial (1963-68) in Frankfurt, both of which dealt with Auschwitz and forever made it the central symbol of Nazi crimes.

The Eichmann trial made history as the first internationally televised trial, being broadcast to 37 countries, and left a lasting intellectual impact through Hannah Arendt's reports and her subsequent book, which provided a new framework for understanding Nazi crimes.

The Auschwitz Trial in Frankfurt, by contrast, served as a kind of domestic German reckoning. In 1960, Robert Mulka, a former SS Hauptsturmführer and Auschwitz camp adjutant, was arrested for multiple murders. In the ensuing 'Auschwitz Trial' (1963-1965), prosecutor Fritz Bauer brought 22 defendants to trial - Bauer's name would not become widely known until 2015 with the release of the German film The People vs. Fritz Bauer.

The trial had a profound emotional impact on all those involved - judges, witnesses and prosecutors - and sparked a debate on the abolition of the statute of limitations for crimes against humanity. However, sentences remained mild: only six indictees were convicted as perpetrators, while others were found to be accomplices. The prevailing view was still that responsibility for genocide lay mainly with commanders, while others were seen as merely following orders.

The immediate social impact of the trials remains difficult to measure. While West Germany remained silent, the state-controlled East German media weaponised the trials as anti-Western propaganda.

But the winds of change were beginning to blow: in the academies and across the streets. The dominant politics of forgetting began to show cracks in the mid-1960s.

Following the Eichmann and Auschwitz Trials, along with philosophical and psychological debates about memory, the cultural perspective shifted dramatically. For the first time, focus moved away from protecting broader society's reputation toward the perspective of the Jewish victims, who had been largely excluded from the dominant narrative of the past.

When the 1968 protests erupted in the West, the conflict became generational—not between perpetrators and victims, but between the first post-war generation and their children. It became silence versus shouting, removal narratives versus hard truths to confront.

1968-1970: We Need to Talk!

The end of the 1960s was about breaking the silence - about the past, the present, outdated role models, norms and morals, and the economic system. Above all, it was about demanding radical change.

Under the motto "He who keeps silent is guilty", the children of the post-war generation accused their parents of two things: of being Nazis before, and of keeping silent after.

The youth not only rejected their forefathers but also rejected the new federal state, seeing it as a continuation of the fascist regime it had supposedly replaced. What followed is a well-known story: the protests, the marches, the street violence and the attempts by East German agents to manipulate and direct these protests.

»The war generation erased their past by drawing a line under it, while the second generation drew a moral line separating themselves from that past. The first generation's pragmatic approach meant burying the past in silence —their attitude was "Let's not talk about it anymore!". The second generation's moral line, however, represented a complete break from the past—their stance was “We are different, and therefore we must talk about this past!”«

Assmann, Aleida: Das neue Unbehagen an der Erinnerungskultur. (The new unease about the culture of remembrance), C.H.Beck, 2021

When young people exposed their families' Nazi histories and confronted institutions, did this mark the beginning of German "Erinnerungskultur"? Not yet.

While victims were often used as tools to accuse parents and the state, there was not yet genuine human empathy for the individual destinies of Jews and other victims. It was, rather, the beginning of a transformational journey —a journey that was also starting in politics, as the SPD, led by Willy Brandt, came to power in the German federal government for the first time in 1969.

Looking Eastward: Ostpolitik and Memory-Building.

»This state gained dignity through an act of humility. [...] Here was someone who showed greatness by suppressing his pride and taking on guilt, moreover guilt for which he personally, as an opponent of Hitler and an exile, was least responsible: Here was someone who proved his honor by showing public shame. Here was someone who understood his patriotism in such a way that he knelt before Germany's victims.

I'm not prone to sentimentality when watching TV screens, and yet it affected me like so many others when, on his 100th birthday, they replayed the footage of a German Chancellor who steps back before the memorial in the former Warsaw Ghetto, hesitates for a moment, and then completely unexpectedly falls to his knees - to this day, I cannot watch it without tears coming to my eyes. And the strange thing is: alongside everything else, alongside the emotion, the memory of the crimes, the renewed amazement each time, there are also tears of pride, of very quiet yet certain pride in such a Federal Republic of Germany.«

Speech by Navid Kermani - writer, reporter, journalist and orientalist - at the ceremony "65 Years of the German Basic Law", 201410 (FULL VIDEO HERE)

Willy Brandt's genuflection in December 1970 before the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 has become iconic: it is part of the German school canon, one of the most significant moments in the development of Ostpolitik, and appears among the test questions for citizenship applications. It marked a fundamental turning point in the way memory shaped diplomacy. But what about remembrance as a shared culture? Was this its moment of birth? No, not yet. We are not there yet.

The act was simply grandiose, and today most Germans would agree. At the time, however, it provoked mixed reactions on both sides of the German-Polish border and around the world.

In the world, his kneeling was honoured by Time magazine as 'Man of the Year'. The following year he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the only German to receive the award since the Second World War.

In Germany, the youth of the '68 generation were enthusiastic. Their parents were less supportive, seeing the act as "unnecessary guilt" or even a betrayal of the millions of Germans expelled from the East. A poll published by Der Spiegel found that 41% of respondents thought the gesture was appropriate, while 48% thought it was overdone.

In Poland, people were confronted with a history that wasn't their own: Chancellor Brandt knelt before the Jewish victims, but not before the Polish resistance fighters, whose Warsaw Uprising of August-October 1944 occupies a central place in Polish memory. At the time, there was no monument to the event - a memorial could only be erected after Poland's liberation from Soviet hegemony. As a result, the Polish media largely played down Brandt's genuflection.

And frankly, even today, on the German side of the border, most people confuse the Ghetto Uprising of 1943 with the Warsaw Uprising of 194411. This gap in the culture of remembrance of Eastern Europe remains a significant issue: stories from behind the former Iron Curtain remain a grey area. Only the tragedy unfolding in Ukraine has begun to pierce this fog with a powerful spotlight.

1970-1978 Piercing the Fog with the Power of Filming: Between Memory and Propaganda.

Media matters. It always has: since radio became the megaphone of dictators, movies persuaded Americans to join WWII, and the press earned its title as the fourth estate, storytelling shapes both conscience and memory, whether through documentaries or fiction.

Taking inspiration from the Soviet Union's pioneering use of film for education and propaganda, East Germany invested heavily in shaping collective memory through cinema. Their film and television productions surpassed West Germany's in both volume and quality until the late 1970s.

Until the end of 1989, East German film and television produced fifty feature films and more than eighty television productions depicting Jewish experiences before and after the world wars12. Some centered on Jewish protagonists, while others featured Jews as peripheral characters. These productions were inherently political due to the nature of the state.

East Germany benefited from having many Jewish intellectuals—poets, writers, movie directors, and theater authors—who chose to remain. These artists could combine their political commitment to the state's antifascist rhetoric with their personal, empathetic perspective on their lived experiences, despite occasional inner tensions. This combination was notably absent in West Germany.

In 1972, the GDR/DDR had its big broadcasting moment when state television broadcast "Die Bilder des Zeugen Schattmann” (The Pictures of the Witness Schattmann), a four-part television film based on the autobiographical novel by the writer, painter and Auschwitz survivor Peter Edel.

The story follows Frank Schattmann—Edel's alter ego—and his Berlin Jewish family through different time periods, recounting their experiences of discrimination and persecution, their involvement with the Communist Party and the resistance movement, and their deportation to concentration camps, followed by liberation and return. The narrative is framed by the GDR court case against Konrad Adenauer's Secretary of State, Hans Maria Globke, one of the aforementioned state actions against West Germany.

The last episode was filmed in Auschwitz. Peter Edel himself returned to the death camp he had survived to supervise the shooting. This marked the first time a German film crew received permission to film inside the memorial site—from the Oświęcim train station to the overgrown ramp in Birkenau, through the demolished crematoria and main camp streets, into the barracks, all under sunny skies filled with birdsong.

This historic filming preceded by seven years the Western media event that would forever change television history and irreversibly shake the German soul: the American TV series "Holocaust".

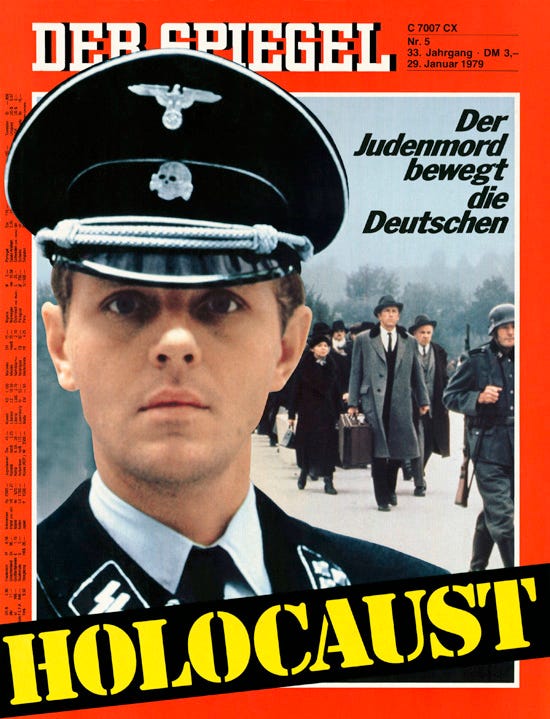

1979: "Holocaust" and a nation's catharsis.

We are now approaching moments that many of us remember firsthand—whether as children or adults—or have come to know as media enthusiasts. The "Holocaust" television series stands as one such pivotal moment, inspiring decades of essays, stories, and interviews. It is considered one of the most important events of 1979, along with the Iranian revolution, the election of Pope John Paul II, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the rise of Deng Xiaoping and Margaret Thatcher.13

"Holocaust" aired in the USA in April 1978, on NBC in four 120-minute episodes, drawing 120 million viewers. The broadcast proved to be a watershed moment—not only as a major TV event but also a milestone in raising Holocaust awareness in America.

The seven-hour TV series follows three German families from 1935 to 1945: the Jewish Weiss family, who endure escalating persecution; the Helms family, connected to the Weisses through marriage; and the Dorf family, whose unremarkable patriarch Erik advances within the Reich Security Main Office while committing Nazi atrocities.

In West Germany, politicians and journalists across party lines expressed immediate outrage after the series aired in the United States—despite almost none of them having seen it. They condemned Holocaust as Hollywood profiteering that trivialized Jewish suffering. Headlines declared "The extermination of Jews as a soap opera" and "The genocide is shrunk to Bonanza proportions."

The series was sold to over thirty countries and broadcast abroad starting in autumn 1978. The German Foreign Office monitored the reception worldwide, hoping to find negative reactions. But it was a huge success everywhere, including Israel.

The German public broadcaster WDR (Westdeutsche Rundfunk) acquired the broadcasting rights but faced immediate criticism, with opponents accusing it of yielding to political pressure from the Social Democratic SPD and denouncing it as "a red broadcaster!".14

The main opposition came from Christian Democratic politicians and the Bavarian CSU. Yet the pressure to broadcast the series in Germany became overwhelming: media outlets in America, Britain, and Israel were keenly watching how Germans would respond to the series following its broadcast in their countries. Germany could no longer remain passive while this globally distributed series aired.

Due to these political tensions, efforts were made to broadcast the series outside the main ARD channel and after prime time. Eventually, the series aired on WDR's third channel—which focused on cultural programming—and was simulcast on other regional state channels. To provide additional context (or to mitigate the impact?), West German broadcasters supplemented the series with their own productions: documentaries, discussion panels, and a comprehensive educational program.

Finally, the scissors. The WDR editors made several post-editing cuts to the series: they reordered some scenes to better explain historical context, removed a scene showing "Execution of Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto by men in Polish military uniforms" to avoid debates about anti-Semitism in Poland, and cut also the original ending: while the American version ended with Jewish children leaving for Palestine and a separated couple reuniting, the German version concluded with the suicide of SS man Dorf.

Despite security concerns—right-wing radicals even bombed TV transmission towers to sabotage the broadcast week—the series aired as planned. The response exceeded all expectations.

Over twenty million Germans watched at least one episode, with a quarter viewing all four. By the final episode, fourteen million viewers were watching. For context: in 1979, Germany's total population was approximately 78,147,901 including the newborns.

It was both a television ratings triumph and an emotional bombshell. After the broadcast of Holocaust, a brief window was opened for viewer calls, but it was quickly overwhelmed by tens of thousands of people15. A student manning the phones described the situation: »It's really bad. They all finally want to get it off their chests. Many are crying. And the crying cannot be recorded.« One woman called in sobbing: »We've been crying here the whole time! How was it even possible that something like this happened? And why didn't the Allies, who knew everything, do something?«16

Others came forward with information about crimes they had known but never spoken of before. Former army members called to insist they shouldn't be confused with the Einsatzgruppen and SS concentration camp guards. Letters poured in—some highly critical, some openly pro-Nazi, but most expressing long-suppressed feelings finally finding release.

It became a form of collective psychological catharsis for emotions buried deep within. Families began having difficult conversations at home. International media reported on the German response with astonishment, stunned by the profound impact the series had on the country.

Holocaust brought to the German people what post-war re-education, public speeches, documentaries and the distant world of academia could not: empathy and emotion.

The series enabled viewers to identify with both victims and accomplices. The Holocaust script, written by American authors, was deliberately crafted this way: it was easier to connect with an assimilated, middle-class Jewish family than with people from the shtetls, and with an ordinary desk-bound perpetrator rather than monstrous villains.

BUT: nearly a third of Germans still maintained that National Socialism had been a good idea that was simply poorly implemented. However, the remaining two-thirds experienced a profound shift in their self-perception and worldview. Their collective conscience had finally awakened.

Was this, then, the beginning of German "Erinnerungskultur"? Indeed it was, as the seeds of a new historiography—based on oral histories—were emerging. The '68er generation was transforming their urgent cry of "We need to talk" into research, documentation, memoirs, and literature that would flourish throughout the 1980s and even more in the 1990s. This broadcast served as a catalyst for processes already underway.

This turning point also triggered a change in foreign policy, with increasing attention to humanitarian crises, especially when confronting potential genocides. This manifested in a large, empathetic acceptance of refugees. The story of the Vietnamese Boat People in Germany is often overlooked, yet West Germany accepted more than 35,000 refugees between 1979 and the early 1980s—far exceeding their initial commitment of just a few thousand. These refugees later shared stories of unexpected warmth and humanitarian acceptance from their German hosts17.

1980–1989: Foreign Policy Challenges, Social Tensions and Historical Debates.

The last decade of the Bonn Republic was marked by terrorism from both the left and the right. It was an era of new fears - especially of nuclear war. It was also a time of fierce, confrontational debates between right-wing and left-wing intellectuals in West Germany, where such discourse was possible. In East Germany, intellectuals were not silent either, but many had to flee or were expelled from the GDR to West Germany.

The seeds of the German culture of remembrance were sown in those years.

From 1979, silence gave way to words - through books, family memoirs (which spawned a whole genre of grandchildren and great-grandchildren coming to terms with their families' Nazi past) and conferences.

The '68ers, now in their forties, developed this new stream of words. Their expressions were no longer mere slogans, but were driven by a genuine curiosity about the individual fates of victims and perpetrators. Young professors began to give lectures on the exclusion and expulsion of Jewish colleagues from universities. Citizens' initiatives researched the names of expelled and murdered Jews, contacted their relatives and invited them to visit their former towns. Numerous researches shed light on some of the darkest aspects, such as Nazi medical experiments.

However, the direction and depth of this movement to develop memory remained unclear.

The key moments of this decade illuminate the struggle: each event, whether national or international, sparked debate and was interpreted through the lens of Germany's contemporary situation.18

1980: The United States Holocaust Memorial project.

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter established the Commission for the Creation of a U.S. Holocaust Memorial. The project began rolling out in the early 1980s, with completion planned for 1993. For the West German government, the American project did not serve as inspiration but rather as a source of anxiety: they feared Germany's history would be reduced to the Third Reich and the Holocaust, with unforeseeable consequences for the country's international standing.

What Germany failed to grasp was that the American debate about Holocaust remembrance was primarily an internal struggle over the Holocaust's significance in American life. This misunderstanding led to disturbing public statements from West Germany, where some openly accused American Jews of exploiting Holocaust memory for political or financial gain at Germany's expense—hardly a sign of true reconciliation.

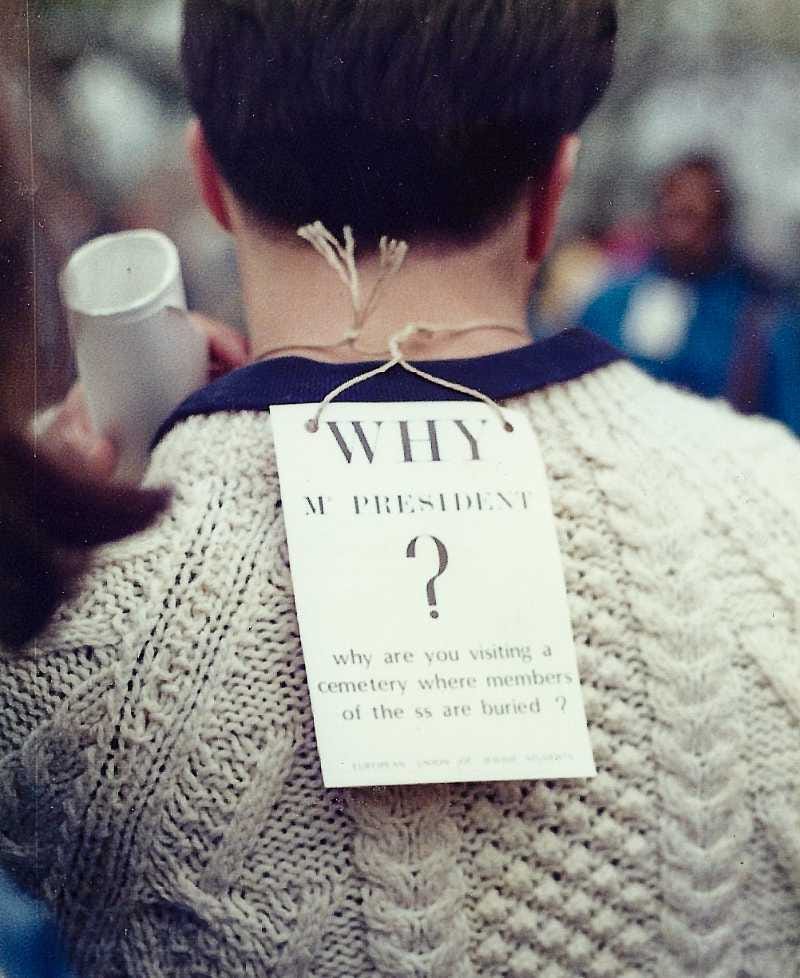

1985: The Limits of Inclusive Memory.

A particularly controversial moment occurred in 1985, when Chancellor Helmut Kohl and Ronald Reagan visited a military cemetery in Bitburg on 5 May. The cemetery, close to the Luxembourg and Belgian borders, also contained graves of SS members. This attempt at inclusive commemoration sparked outrage and demonstrated how efforts to reconcile national pride with historical responsibility could backfire.

Chancellor Helmut Kohl - a historian by training - sought to 'normalise' history by promoting a more assertive German identity while maintaining reconciliation efforts. This proved to be an incredibly difficult balancing act in the 1980s. Similarly, a proposed inclusive memorial in Bonn to honour all victims of the Second World War reached an impasse.19

May 8, 1985. Federal President Weizsäcker's speech.

8 May 1985: 40 years after the end of the war, the day of Germany's unconditional surrender. To mark the day, Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker (1920-2015) gave a 44-minute speech on the remembrance of 8 May and its significance.

However, a single sentence from that speech sparked an unprecedented controversy. This is the kind of heated debate that often erupts when one extracts a single line from a long, nuanced speech:

»Und dennoch wurde von Tag zu Tag klarer, was es heute für uns alle gemeinsam zu sagen gilt: Der 8. Mai war ein Tag der Befreiung. Er hat uns alle befreit von dem menschenverachtenden System der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft.«

»Yet with each passing day, it became clearer what we must all collectively acknowledge today: May 8th was a day of liberation. It freed us all from the inhuman system of National Socialist tyranny.«

»May 8th was a day of liberation«

Some of the strongest reactions came from CDU colleagues, who called the interpretation 'one-sided'. CSU Bavarian Prime Minister Franz Josef Strauß seized the opportunity to make one of his frequent calls for a final break with the past: "The eternal coming to terms with the past as a permanent social penance paralyses a people!" There was widespread indignation on the West German political right: how could an unconditional surrender be celebrated, and how could Germany be expected to be grateful to its occupiers?

Do not underestimate the long-standing effect of this controversy: it explains one of the rare occasions of visible internal division within the AfD party, with one of its two leaders, Tino Chrupalla, willingly participating in the Moscow embassy's May 9th celebration, while his colleague Alice Weidel rejected it as an unthinkable tribute to the occupiers. The past does not pass. The past, including what I am trying to summarize in this revisitation of German memory, continues to weigh heavily on today's politics. Incredible, isn't it? Or perhaps more understandable than we think?

Weizsäcker's speech was more comprehensive—attempting to unite multiple perspectives through a long list of victims to be commemorated: Poles, Sinti, Roma, resistance fighters, Soviet victims, and German civilians. The speech also presented a nuanced narrative regarding German guilt:

»Most Germans had believed they were fighting and suffering for the good cause of their own country. And now it turned out: All of this had not only been futile and senseless, but had served the inhuman objectives of a criminal leadership.« […] »There is no such thing as guilt or innocence of an entire people. Guilt, like innocence, is not collective, but personal.«20

The controversy over this speech continues to this day among critics of German memory culture. They argue that speaking of liberation, while implying that many served a criminal leadership in good faith, merely perpetuated an exculpatory narrative.

By separating the German people from National Socialism, this rhetoric demonised a few perpetrators while placing most of Germany in a victim-centred culture of remembrance. This critique, as articulated by author Per Leo in 2021, shows that the culture of remembrance remains a work in progress, fraught with tensions (more in the next post, PART THREE)21.

1986/87 The Historians´ Dispute: “The Past That Will Not Pass”.

Then came another major debate, which remains unresolved to this day. The Historikerstreit (Historians' Dispute) questioned whether the Holocaust was an unparalleled crime or comparable to other atrocities, and examined its role in shaping Germany's historical identity.

The controversy began with an article by historian Ernst Nolte published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in June 1986, challenging the Holocaust's uniqueness. Nolte argued that Nazi atrocities were a reaction to Bolshevik crimes—specifically the Gulags and Stalin's purges—suggesting a historical causality between them. He framed the genocide of the Jews as part of a broader pattern of 20th-century totalitarian violence:

»Did the National Socialists, did Hitler perhaps only carry out an 'Asian' deed because they regarded themselves and their peers as potential or actual victims of an 'Asian' deed? Wasn't the 'Archipelago Gulag' more original than Auschwitz? Was not the 'class murder' of the Bolsheviks the logical and factual precedent of the 'racial murder' of the National Socialists? (…) Did Auschwitz perhaps stem in its origins from a past that would not go away?«22

He also questioned whether the widespread desire to "draw a line" under the past held merit, suggesting that discussions of "German guilt" mirrored Nazi propaganda about "Jewish guilt" and diverted attention from more recent atrocities, such as the occupation of Afghanistan (1979-1989).

The opposition to this view was led by philosopher Jürgen Habermas, who published a forceful reply in Die Zeit one month later, which he presented as nothing less than a "declaration of war" against Nolte and his followers. The Holocaust—Habermas reminded—was a unique and unparalleled atrocity that was impossible, and incredibly dangerous, to "normalize." He accused: »Anyone who wants to make us blush over this fact with a phrase like 'obsession with guilt' [...] is destroying the only reliable basis of our ties to the West.« The debate turned political—it was about Germany's new position in the Western world. Letters poured in from readers and other intellectuals for almost a year. Like the many subterranean currents of German memory, the debate never truly ceased to flow.23

1987 Topographie des Terrors:

The Material Response to the Historians' Debate.

On July 4, 1987, as part of Berlin's 750th anniversary celebrations, the first exhibition now known as the Topographie des Terrors (Topography of Terror Documentation Centre) opened on the site of the former Secret State Police (Gestapo) Headquarters, which operated there from 1933 to 1945. During the Nazi era, this was Berlin's most dreadful address. After the war, it became merely a plateau of leveled ruins where a recycling company stored building rubble.

In 1983, a local association drew attention to this forgotten site in Kreuzberg (West Berlin), near Potsdamer Platz. After some discussion - in the 1980s, as we can see, anything to do with remembrance was hard to come by - archaeological excavations began. Four years later, with the temporary exhibition, the archaeology of the Nazi era began, marking a new period of rediscovered sites becoming living memory. When I first visited, it was still temporary and provisional - it was not until 2010 that it became the documentation centre it is today, attracting school groups and tourists interested in history.

1988: Shadows of the East.

During Berlin's 1987 anniversary celebrations, the First Jewish Culture Days were held in Prenzlauer Berg, East Berlin. This event was organized by a new generation of GDR citizens—both Jewish and non-Jewish—who chose to ask critical questions while taking positive action to revive Jewish life in their country.

However, not everything went well. When SED leaders launched a campaign promoting remembrance culture during the fiftieth anniversary of the November pogroms in 1988, much of the population rejected it.

The state-enforced anti-fascism had created too many gaps in collective memory. Paradoxically, the more the state emphasized its anti-fascist stance, the less effective it became at combating resurging antisemitism—which, after Reunification, was found to be intertwined with neo-Nazism.

This represents one of the many complex challenges that reunified Germany had to address. The following 35 years saw a comprehensive program to develop the Culture of Remembrance, encompassing monuments, official statements, substantial funding for researchers and foundations, and extensive literature. This led to the canonization of Remembrance—a model many of us envied for a long time.

But as seen in this review, much was built on unstable foundations and unresolved debates. How Germany transformed from being the "world champion of memory" to its current state of confusion, raising fears that this culture might have been just "a grand deception," will be the subject of the next post: PART THREE: “1990 to Today: United and Confused”.

"A layer of thin ice": What Has Happened to the German Culture of Remembrance? PART ONE

»Germans must bear responsibility. However, responsibility is not the same as guilt. Those who do not feel guilty and are not guilty of Nazi crimes nevertheless cannot escape the consequences of a policy that too large a part of the same people had willingly joined.«

Frederick Taylor: Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, HarperCollins 2005 (Eng.) and Pantheon 2008 (Ger.)

In Das neue Unbehagen an der Erinnerungskultur. (The new unease about the culture of remembrance), 2021, Aleida Assmann—one of Germany's leading experts in cultural anthropology and memory—describes this as a "consensus of silence" or "pragmatics of silence." While this silence made adapting to post-war life easier by avoiding moral confrontation, it created an uneasy coexistence between victims, perpetrators, and accomplices. This pact of silence particularly harmed the victims. The cost of this silence would become clear in 1968, when the children's generation condemned both their parents' generation and the entire political system of West Germany as complicit in guilt.

Biess, Frank: Republik der Angst, 2019. analyzes the Federal Republic through the lens of collective fears: post-war retribution fears, 1950s nuclear and communist threats, concerns about automation and authoritarianism, and 1980s apocalyptic anxieties. Rather than evaluating these fears' legitimacy, he examines how they shaped Germany's development. His thesis suggests that war and violence experiences both challenged and reinforced the nation's democratic evolution. The book concludes by examining whether today's German fears of war, immigration, and terrorism remain uniquely tied to its past or reflect broader Western anxieties.

L. Rensmann, Guilt, Resentment, and Post-Holocaust Democracy, Antisemitism Studies, 1, 2017, DOI: 10.2979/antistud.1.1.01.

»Mit großem Schmerz sagen wir: Durch uns ist unendliches Leid über viele Völker und Länder gebracht worden. Was wir unseren Gemeinden oft bezeugt haben, das sprechen wir jetzt im Namen der ganzen Kirche aus: Wohl haben wir lange Jahre hindurch im Namen Jesu Christi gegen den Geist gekämpft, der im nationalsozialistischen Gewaltregiment seinen furchtbaren Ausdruck gefunden hat; aber wir klagen uns an, daß wir nicht mutiger bekannt, nicht treuer gebetet, nicht fröhlicher geglaubt und nicht brennender geliebt haben.«, The Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt, October 19, 1945

A. Walther, Stubborn Remembrance. The Role of Shoah in East German Anti-Fascism, in Another Country: Jewish in the GDR, Jüdisches Museum Berlin, 2023.

To emphasize the purely functional nature of the agreement, critics often cite Chancellor Adenauer's words from a 1966 interview—recently referenced by Germany's leading satirist, Jahn Böhmermann—where he described his commitment to Wiedergutmachung with Israel and the Jewish people: "furthermore the power of the Jews even today, particularly in America, should not be underestimated and therefore I thought very carefully and very consciously and in my opinion that was the reason why I put all my strength into bringing about as best I could a reconciliation between the Jewish people and the German people." While the words preceding this ambiguous statement acknowledge the crimes and injustice committed, this 1966 interview remains divisive among critics of Germany's Culture of Remembrance: "we had done so much injustice to the Jews, we had committed such crimes against them that they had to be atoned for or made good somehow if we wanted to regain respect among the peoples of the earth." —> Listen on Youtube (1:11 mins)

The Luxembourg Agreement: the mirage of reconciliation, K-Revue, September 22, 2022

Rede von Dr. Navid Kermani - zur Feierstunde „65 Jahre Grundgesetz“ / Bundestag Archiv

Assmann, Aleida: Der europäische Traum. Vier Lehren aus der Geschichte, (The European dream. Four lessons from history), 2018

Schoß, Lisa: Jewish Experiences in East German films, in Another Country: Jewish in the GDR, Jüdisches Museum Berlin, 2023

Bösch, Frank: "Zeitenwende 1979: Als die Welt von heute begann" (“Turning Point 1979: When Today's World Began”), 2019

Schulz, Sandra: Film und Fernsehen als Medien der gesellschaftlichen Vergegenwärtigung des Holocaust (Film and television as media for social visualisation of the Holocaust), via BPB.DE, April 19, 2023

“Holocaust": Die Vergangenheit kommt zurück ("Holocaust”: The past is coming back), Der Spiegel, January 29, 1979 (free to read)

Bösch, Frank: Zeitenwende 1979: Als die Welt von heute begann (Turning Point 1979: When Today's World Began), 2019.

Assmann, Aleida: Das neue Unbehagen an der Erinnerungskultur. (The new unease about the culture of remembrance), 2021

Eder, Jabob: The Journey is the Destination: German Politics of Remembrance and Their Contradictions, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, August 21, 2021

»Die meisten Deutschen hatten geglaubt, für die gute Sache des eigenen Landes zu kämpfen und zu leiden. Und nun sollte sich herausstellen: Das alles war nicht nur vergeblich und sinnlos, sondern es hatte den unmenschlichen Zielen einer verbrecherischen Führung gedient.« […] »Schuld oder Unschuld eines ganzen Volkes gibt es nicht. Schuld ist, wie Unschuld, nicht kollektiv, sondern persönlich.« Gedenkveranstaltung im Plenarsaal des Deutschen Bundestages zum 40. Jahrestag des Endes des Zweiten Weltkrieges in Europa

Leo, Per: Tränen ohne Trauer. Nach der Erinnerungskultur (Tears without sorrow. On the culture of remembrance), 2021

Nolte, Ernst: Vergangenheit, die nicht vergehen will (Historikerstreit), 6. Juni 1986, via 1000Dokumente.de

„Ein Kampf um die Seele der BRD“ ("A Battle for the Soul of the FRG"), August 18, 2018, Deutschlandfunk

Share this post