"A layer of thin ice": What Has Happened to the German Culture of Remembrance? PART ONE

From praise to scepticism: Germany's culture of remembrance faces a reality check as surveys reveal not only limitations in how Germany remembers its past, but gaps in basic knowledge itself.

»Germans must bear responsibility. However, responsibility is not the same as guilt. Those who do not feel guilty and are not guilty of Nazi crimes nevertheless cannot escape the consequences of a policy that too large a part of the same people had willingly joined.«

Willy Brandt

in „Verbrecher und andere Deutsche“

(Criminals and other Germans), 1946

From "the greatest political education success" to "post-war Germany's biggest lie," through all its limitations and "yes, but also…" caveats, everything has been said and written about German remembrance culture in recent years, both in Germany and around the world. But recent surveys suggest that it's not so much the "culture of remembrance" at stake but memory itself—or rather its absence.

A three-part journey exploring history and data, pivotal moments and the competing narratives that shaped —and now challenge— Germany's Culture of Remembrance.

27 January in Berlin: Flags fly at half-mast and flowers are placed at memorials. Events large and small all over Germany. On TV and online, the ceremony in the Bundestag's plenary session. I usually avoid public ceremonies, but this one is different: it culminates in the testimonies of survivors and their descendants. I wrote about this last year - moments that truly touch the heart. Parliaments can inspire deep emotion. Politics can fly high.

But not in this 2025. The tone has shifted from solemn dignity to the cacophony of a drunken brass band. In recent weeks we've heard the unthinkable: renewed calls to "put the past behind us" and look to the future with German pride (Elon Musk); Adolf Hitler defined as a leftist, almost a communist (Alice Weidel, AFD); Holocaust survivor Roman Schwarzman, who spoke in the Bundestag on 27 January, returning his newly awarded Federal Cross of Merit the same day, feeling betrayed by the state that had honoured him.

Nothing new under the sun, really. We live in cacophonous times, partly because the guardrails of public discourse have fallen away. And when inhibitory controls fail, the past tends to resurface.

Take the renewed invitation to come to terms with the guilt of the past: here in Germany we know it as "Schlussstrich", which means “drawing a line”. The debate about this line, here known as the "Schlussstrichdebatte" has always come along like a karst river with the other two keywords of German memory: “Vergangenheitsbewältigung", coming to terms with the past, and “Erinnerungskultur”, the culture of remembrance.

“Draw a line and move on”? This desire has been expressed since the birth of the Federal Republic of Germany1:

»These ten years have brought an immeasurable amount of confusion, misfortune, and suffering upon the German people during the war and post-war period. Now [...] this new constitutional situation makes it seem desirable that a line be drawn under a series of actions« so spoke in 1949 Hermann Kopf, CDU Member of Parliament, after the approval of West Germany's constitution.

»The Social Democratic Party also believes that a line must be drawn under the entire chapter of political cleansing« said Fritz Erler, SPD Member of Parliament, in 1950

»It is high time that we step out of the shadow of the Third Reich and out of the aura of Adolf Hitler and become a normal nation again.« are the words of Franz-Josef Strauß, chairman of the Bavarian CSU Christian Social Union, 1986

What about the “leftist” Hitler? This also comes from the past, and not so far back. Here is Edmund Stoiber, secretary-general of the CSU, being interviewed by Bavarian public television in 19792:

»Both Hitler and Goebbels were Marxists at heart." And: "Hitler even declared once, I must quote from memory, that National Socialism was the most logical and best consequence of Marxist doctrine.«

Nothing new under the sun, so why bother?

But on the same day, a real wake-up call came with the publication of an eight-country survey On Holocaust knowledge and awareness conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (aka Claims Conference). The alarm bells began ringing when it came out that3:

● Around 40 percent of Germans aged 18 to 29 said they did not know that some six million Jews were murdered during the Nazi era.

● 12 percent of young adults in Germany had never heard of the terms Holocaust or Shoah. (In Austria, the figure was 14 per cent, and in France as many as 46 percent of young people.)

● 18 percent of German respondents cannot name a single concentration camp, a figure that climbs to 26 percent among those aged 18–29.

In a country where the word "crisis" (Krise) readily morphs into "catastrophe" (Katastrofe), it was almost inevitable to see news headlines linking Erinnerungskultur with the verb "failed" (gescheitert) —whether they included a question mark or not:

Remembrance culture in Germany: failed or misjudged?

History in dispute: Has the German culture of remembrance failed?

The second thought - Has the culture of remembrance failed?

and so on.

Once we recover from the incoming federal elections, new debates will fill conference halls. "Debattenkultur" — the culture of debate — is another prized Made in Germany asset that has recently been struggling.

Yet: how can we label a cultural project a failure when it's still celebrated worldwide as a success?

Twenty years ago, when I started spending more time in Germany, I fell in love with the German Erinnerungskultur. Coming from a chronically forgetful Italy, I was filled with admiration seeing countless books on bookstore shelves, public events every week, and quality historical journalism.

Recently I was commissioned to write a piece for a book on the German language, focusing on its socio-cultural aspects. Now free of my initial infatuation, I proposed to the Italian publisher a more nuanced approach to German memory culture, one that would examine its significant fractures and ongoing debates. I had to backtrack and return to a simpler, more black-and-white narrative —those who had confronted their past versus those who never would. The reason? Attempting to summarize the evolution of German memory culture, particularly as it fragments into countless modern debates and themes, leads more often than not to mental exhaustion.

The topic has followed a complex trajectory: first over-simplified, then over-complicated - first too narrow, then too broad, and finally becoming a tool for petty political polemics.

The result? Confusion and an avalanche of academic jargon incomprehensible to most: "multidirectional memory", "intersectional lines of remembrance", "vanishing points of history", "integrative memory". Meanwhile, the fundamental aspects of memory - what happened, when, where, by whom and why - have faded into the background.

After getting a headache from days of reading and re-reading, I can somewhat sympathise with those who say: "Let's draw a line and move on". But today I want to take a different approach. And to avoid overwhelming both you and myself, I'm going to split this into three posts:

A snapshot of the present, drawing on recent research into knowledge and awareness to identify both established touchstones and gaps in memory. = More data, less storytelling.

A history of the development of memory culture, acknowledging the existence of two Germanies until 1990 and tracing the key tensions and pivotal moments. = History and anedoctes.

Finally, an account of the present, which I call "the great confusion" - the period from 2020 onwards, when the discourse became increasingly complex and, at times, confrontational. = A chronicle of our days, with no claim to completeness.

PART ONE: A Snapshot of the Present.

Among the many surveys and studies, those conducted by the German Foundation "Remembrance, Responsibility and Future" (German acronym EVZ) are particularly valuable. They have been carried out systematically since 2017. Here I examine the two most recent studies: MEMO V 20224 (covering the general population) and MEMO YOUTH 20235 (focused on student youth aged 16-25), most of which were conducted before the war in Ukraine and the events of 7 October.

I look at the results of the research in relation to these three key questions:

How important is remembering the past for Germans today? What's the attitude toward remembrance?

How deeply does the National Socialist past still influence German identity and the ability to express national pride?

How accurate is this collective memory, what are its main gaps and blind spots, and why do they exist?

1. Attitudes Toward Remembrance

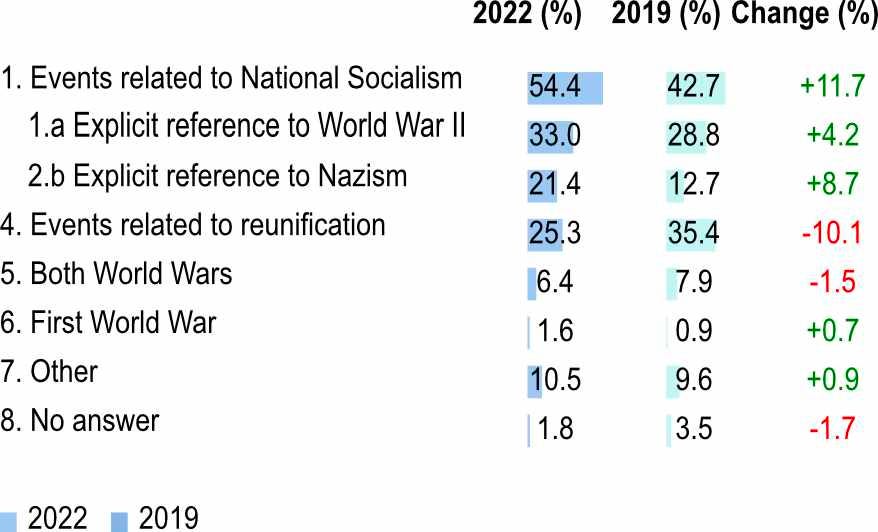

Remembrance is also a matter of setting priorities: despite the catastrophic tone of recent news, these data show that events related to National Socialism are seen as a top priority, now more than before.

Which event from German history should future generations in Germany remember most, in your opinion?

Young people between the ages of 16 and 25 also consistently emphasised Nazi themes. However, certain topics that feature prominently in academic and journalistic discussions were absent from their schooling and personal experience, and therefore also ranked low in their attention - notably Germany's colonial history:

Are there certain past events or time periods that you personally find particularly important?

These young people, mostly students, acknowledge that the official struggle for memory overlooks certain aspects of German history:

There is too little discussion in our society about other periods of German history, such as the history and consequences of German colonialism. Do you agree?

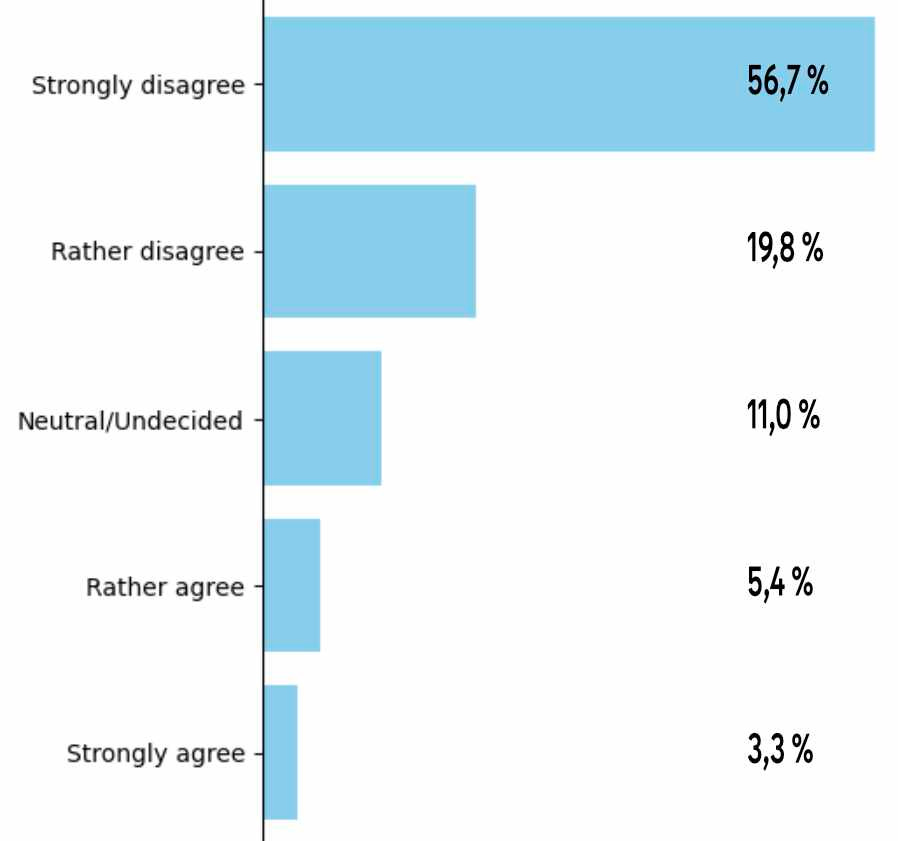

What about the call to “draw a line”? Not among the younger.

When faced with the statement "I don't understand why I should still engage with the history of National Socialism today," young Germans aged 15-29 in the MEMO 2023 study expressed clear opinions:

Looking at the overall population across age groups, the picture reveals some complexity: according to the MEMO 2022, a quarter of Germans think it's time to stop discussing the Nazi past, but a clear majority still disagrees. However: nearly one of five remain undecided.

"It is time to draw a line under the National Socialist German past." Do you agree?

Another survey conducted in autumn 2021 on approximately 1,300 German adults, with research focus on German-Israeli relations, revealed more ambivalent attitudes toward Holocaust remembrance: about half of the respondents expressed a desire to reduce discussion of Jewish persecution and suggested "drawing a line" under this history6.

"Today, almost 80 years after the end of World War II, we should stop talking so much about the persecution of Jews during National Socialism and finally draw a line under the past." Do you agree?

2. Identity shaped by a weighty past and the yearning for national pride.

The question of which past defines national identities fills bookshelves in every country. Ask in France and they'll tell you: "the Revolution". Ask in Serbia and they'll say "Kosovo Polje", the tragic battle of 1389 against the Ottoman Empire. In Greece, they'll talk about the liberation struggles of the 19th century.

It's a different story in Germany, where the relationship between national identity and the memory of the Second World War remains complex. This tension echoed in the political arena with AfD's Alexander Gauland's infamous 2018 statement: »Hitler and the Nazis are just bird shit in more than 1,000 years of successful German history.«

According to the MEMO V research, around two-thirds of Germans recognise the Nazi era as an integral part of their identity, although younger Germans tend to see it as less central to their sense of self.

"The era of National Socialism is a part of German identity." Do you agree?

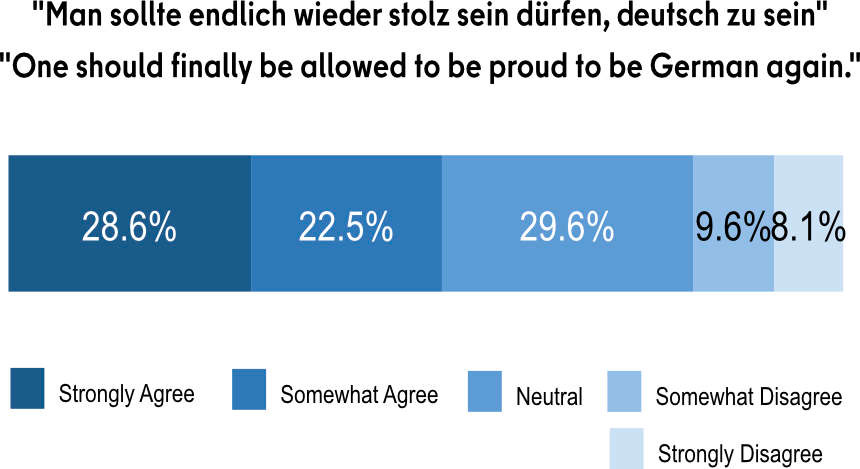

A significant tension exists around national pride, with just over half of Germans expressing a desire to "be proud again." This sentiment —which is entirely understandable— appears more frequently among older generations and those with less formal education. It often correlates with skepticism toward the German memory culture. Sometimes, too, with a certain tendency to believe in conspiracy theories.

“People should finally be allowed to be proud to be German again.” Do you agree?

3. Memory and Its Blind Spots: What We Remember and What We Forget—What We Know and What We Ignore.

The discourse around German memory culture reveals its complexity when examined from multiple angles: Which aspects receive prominence? Which remain in the shadows? Which get ignored entirely—and why? To understand this fully, we must look at how this memory developed and how Germans processed their past after the war (PART TWO, next issue). This becomes even more intricate because Germany experienced not one but two distinct post-war periods.

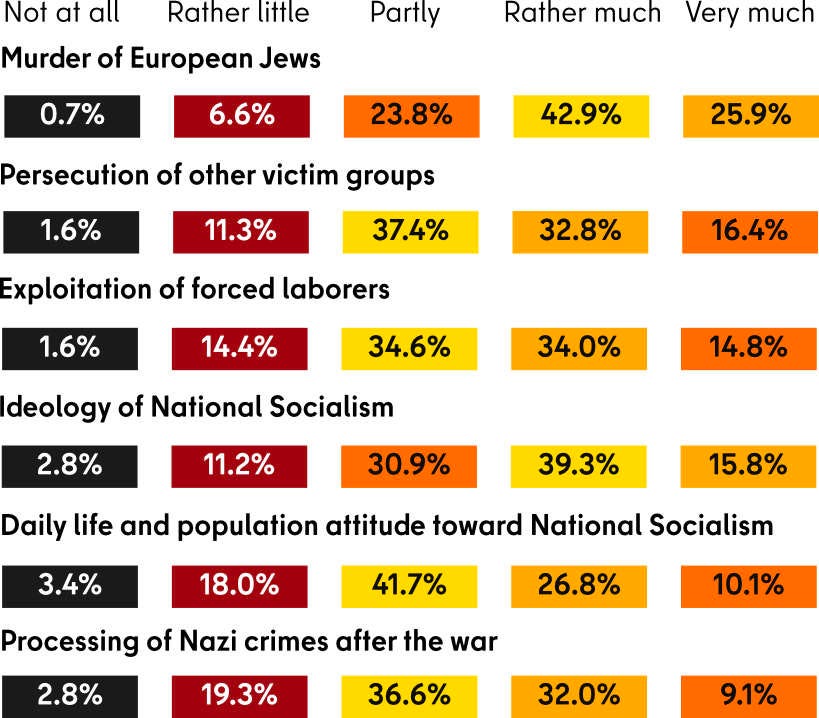

How much do you yourself know about the following aspects of National Socialism?

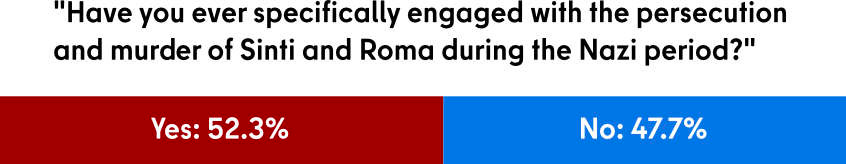

The Sinti and Roma were among the groups whose persecution was long neglected in post-war German memory. According to the 2022 MEMO, just over half of respondents say they have engaged with the persecution and murder of Sinti and Roma during the Nazi period—where "engaged" means having basic knowledge about it. This neglect is particularly striking given the scale of the tragedy: an estimated 220,000 to 500,000 Sinti and Roma were victims of the Nazis' systematic, racially-motivated genocide.

However, when asked further, more than two-thirds of respondents could not name a single memorial site dedicated to these victims of National Socialism - not even the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism in Berlin's Tiergarten (inaugurated in 2012). Moreover, the official European Roma Holocaust Memorial Day on 2 August remains largely unknown throughout Europe.

Much remains to be done about the "other" victims of Nazism – political prisoners, socially marginalised groups, sexual minorities, the more than 3 million Red Army prisoners of war who died of hunger, thirst and disease, and the 26 million forced labourers in the German Reich and occupied territories. Public debate about compensation for forced labourers only began in the late 1990s. Nevertheless, progress has been made: 36% of students aged between 16 and 25 now say they study these different groups of victims 'quite intensively'.

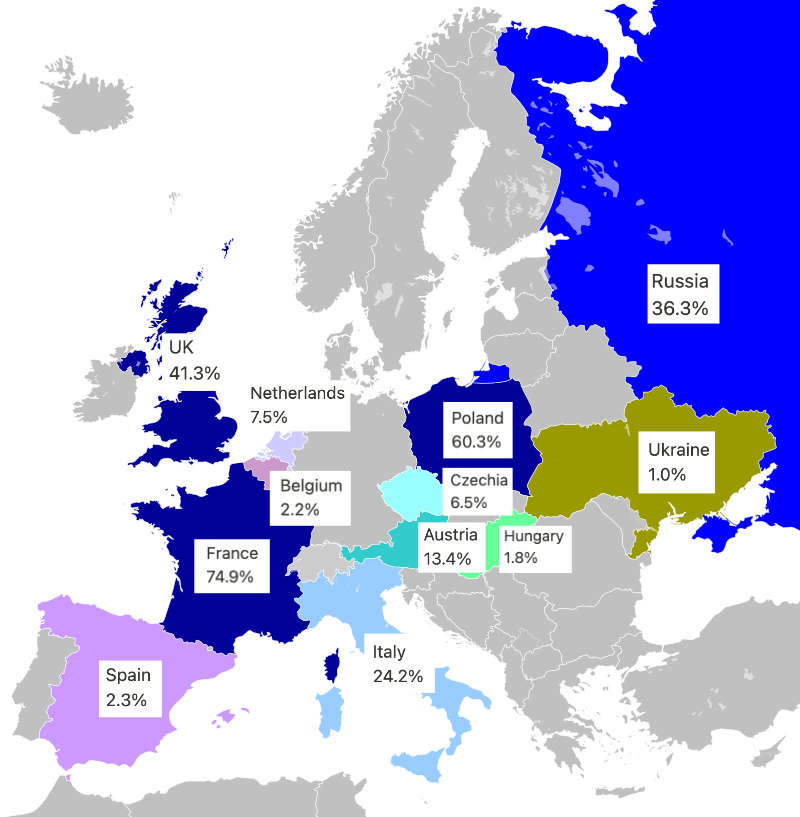

A major blind spot in German memory concerns the atrocities in Eastern Europe. The occupation of Poland, the Soviet Union - without a differentiated view of Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic States - and the Balkans remains poorly understood by the general population.

In West Germany, this stemmed from Cold War politics and a persistent reluctance to challenge the myth of a 'clean Wehrmacht' —a myth not fully dismantled until the 1990s. The West German narrative focused heavily on French reconciliation, particularly through the 1963 Élysée Treaty. Meanwhile, in East Germany, silence became necessary to maintain a new friendship between "brother countries" —both large and small— united under the banner of socialism and anti-fascism.

This dual neglect continues to shape contemporary memory.

When Germans are asked

"Which three European countries, apart from Germany, do you personally associate most strongly with the Second World War?",

their responses starkly reveal these persistent asymmetries: respondents mainly named France, Poland and the UK. Strikingly, only one per cent mentioned Ukraine - despite the fact that within its current borders one in four Jewish victims of the Holocaust were murdered there.

When the focus shifts from the victims to society itself - its collective attitudes during the Nazi period, the way in which the crimes were dealt with after the war, and subsequent self-reflection - understanding becomes more vague and knowledge more limited.

Delving one level deeper into family history reveals the darkest area of memory - where coming to terms with the past (the Vergangenheitsbewältigung) faced its greatest challenges. Yet it was here, in biographical literature, that the most honest and moving accounts emerged. Writers who have dared to examine their own family histories - to look backwards and inwards - have produced some of the most powerful and meaningful works of German literature of the last two decades.

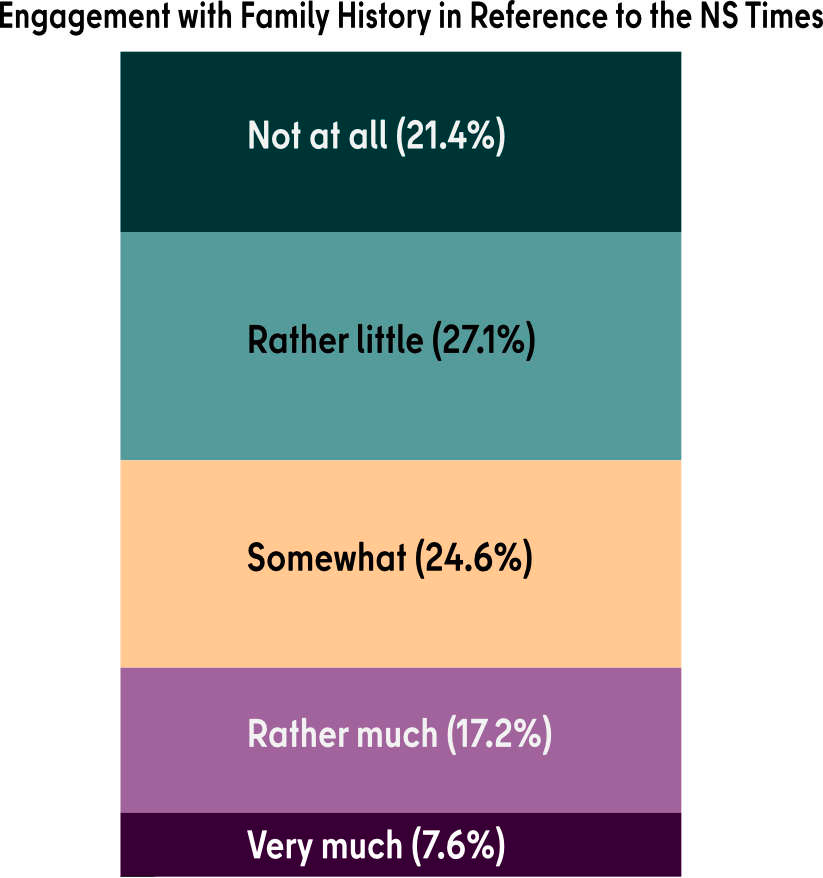

Looking at the data, it's particularly revealing to examine youth responses from the Study-MEMO 2023 (ages 16-25).

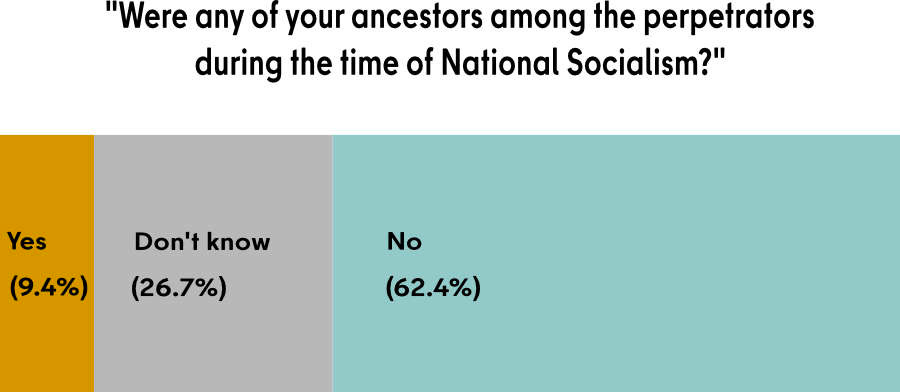

Today, we still see hesitation when it comes to confronting family history—especially when that history might reveal passive acceptance, active collaboration, or enthusiastic participation in the Nazi regime. Though this reluctance is not as severe as during the post-war decades—when a great silence persisted until the 1970s—the topic remains partially taboo. Consequently, most responses to these sensitive questions are either noncommittal or simply "I don't know."

"In your previous engagement with the Nazi era, have you also dealt with your family's history?"

"Were any of your ancestors among the perpetrators during the time of National Socialism?"

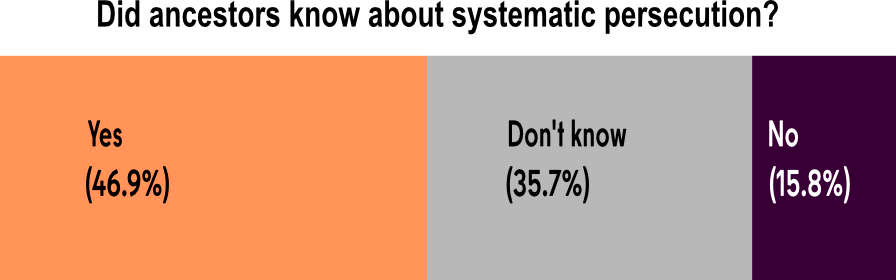

"Would you say that your ancestors during the National Socialist period knew that other people were being systematically persecuted and murdered during this time?"

Despite differences in research topics and timeframes, the findings are largely consistent: this collective memory, shaped over decades by political education, schooling and media, both old and new, reveals both strengths and weaknesses, gaps and uncertainties. While it emerges from a complex process, and despite various attempts - some perhaps clumsy - to consolidate it, this memory remains dynamic and evolving.

Last year, at a public event in Berlin, I met an elderly Jewish woman from East Berlin who had lived through this entire history. After the Wall went up, she had managed to escape to West Berlin—only to return to the East, not out of devotion to socialism, but because of her deep connection to her places and their memories.

When I asked her thoughts on memory culture, she offered an illuminating metaphor: the ice that sometimes covers the small lake behind our houses in winter. Memory is like ice: when thick, it's incredibly strong—try punching a block of ice in the mountains! But when it thins, even the cane she walks with can break it with a gentle tap. This is how she described German memory today: a layer of ice, extremely thin in some parts.

In some areas, the foundation remains solid—no need to panic. However, we must focus on where it's vulnerable, particularly regarding our knowledge and recognition of Eastern European neighbors. We should use this memory thoughtfully in our lives, not for self-censorship, but to better understand the world. This is why it's crucial to look beyond the present moment and understand how we arrived here.

Outside Germany's borders, the development of German memory culture is known mainly through its most dramatic public moments: major trials, scandals, and grand monuments and memorials. In my next post, I'll review this story, including some lesser-known discussions that rarely reach beyond our borders.

The two main studies that I have tapped into, here:

Alexander Fürniß: Irgendwann muss auch mal Schluss sein! Oder? (DEU free to read, It has to end at some point! Right?) Katapult Magazine for Cartograohy and Social Sciences, January 27, 2024

Claims Conference Holocaust Survey, January 23, 2025.

The MEMO V study 2022 surveyed 1,000 Germans across age groups and backgrounds. The participants averaged 49 years old, with equal gender distribution. A majority (89%) were urban residents, with 37% living in major cities of over 500,000 people. Conducted via telephone (CATI) between December 2021 and January 2022, the study included randomly selected respondents from all federal states.

The MEMO 2023 study began with an initial survey of 3,485 young people aged 16-25 (average age 20.8) in September-October 2021. Among participants, 56.9% had qualified for higher education, 24.1% held secondary school certificates, and 11.4% had university degrees. A follow-up survey in September 2022 included 838 participants from the original group who agreed to be contacted again.

The study "Deutschland und Israel heute: Zwischen Verbundenheit und Entfremdung" (Germany and Israel Today: Between Connection and Alienation) was commissioned by the Bertelsmann Stiftung. The data was collected through representative surveys in Germany and Israel in fall 2021, with a German sample of 1,271 eligible voters interviewed by web call (CAWI).