«Ordnung herrscht in Berlin!‘ Ihr stumpfen Schergen! Eure ‚Ordnung‘ ist auf Sand gebaut. Die Revolution wird sich morgen schon ‚rasselnd wieder in die Höh'richten‘ und zu eurem Schrecken mit Posaunenklang verkünden: ‚Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein!»

«Order reigns in Berlin!' You dull-witted henchmen! Your 'order' is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will 'rise up again, clashing its weapons' and proclaim to your horror with trumpets blazing: 'I was, I am, I shall be!»

This was Rosa Luxemburg's last sentence written for Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag), the party newspaper of the Communist Party of Germany. Published on 14 January 1919, the article to which these words belong dealt with the violent suppression of the Spartacist uprising in the streets of Berlin. A day later, Luxemburg was killed - probably with the approval of Germany's Social Democratic chancellor, Friedrich Ebert. The last words of her statement proved prophetic, though not in the way she imagined: what has survived to this day is not so much the revolutionary socialist spirit as the myth of a remarkable human being.

She was a Marxist theorist and political revolutionary, but also a humanist and poetic soul, expressing universal ideals and a deep empathy for humanity and the world. Why is the memory of this seemingly distant historical figure still relevant today? My answer is not political, but literary.

The Last Cold Day: Rosa Luxemburg's Final Hours.

Yesterday like today, on January 15, 1919, it was cold in Berlin. These were days of civil war—filled with revolts, protests, and revolutionary dreams. Sixty-eight days earlier, on November 8, 1918, the day before the proclamation of the post-WWI Republic, Rosa Luxemburg was released from Breslau prison to return to Berlin, where history was unfolding.

First within the SPD, then with the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), and later with the League of Spartakists while preparing for the foundation of the German Communist Party (KPD), Rosa Luxemburg advocated for the birth of a socialist republic. She drafted a political manifesto that, like everything she wrote and spoke, was powerful, passionate, and convincing.

But in those chaotic days, events rapidly spiraled out of control. Protesting against the dismissal of Berlin's police chief -a USPD member- the Spartacist League called for a demonstration that descended into violent clashes. The Spartacist leaders lost control of the situation as the protest evolved into an attempted revolution to overthrow the social democratic government. A civil war erupted, with republican troops loyal to the ruling SPD, along with fascist-inspired Freikorps and counter-revolutionary Prussian Guards, unleashing their fury against the crowds, leaving more than 150 dead.

After the suppression of the January uprising, Luxemburg and her comrade Karl Liebknecht became the government's most wanted and hated opponents. Hundreds of soldiers searched for them as they frequently changed hiding places. On the evening of January 15, while hiding in an apartment in Wilmersdorf (West-Berlin), men of the district Civic Guard broke in. They took the captives to the Eden Hotel on Kurfürstendamm (today Budapester Str. 35), the headquarters of the Guard Cavalry Rifle Division.

Following orders from Waldemar Pabst, the General Staff Officer of the Division, the two were briefly interrogated. Their fate was already decided: while officially ordering their transfer to Moabit remand prison, Pabst secretly instructed his men to ensure they wouldn't arrive alive. Liebknecht was taken by car to the Tiergarten and shot there.

Rosa Luxemburg was struck so violently before even entering the car waiting for her in front of Hotel Eden that she lost consciousness. She too was shot while in the car, and her body was thrown into the Landwehr Canal from the Lichtenstein Bridge. Her body was only found months after her death. Tens of thousands of people lined her funeral procession. Luxemburg's longtime companion Leo Jogiches was murdered a few weeks after her—he had tried to investigate the death of his friend and comrade.

Rosa Luxemburg: not one, but many memories. Some, still controversial.

The memory of those days still divides the social-democratic SPD (heir to the Weimar social democracy that imprisoned Luxemburg and probably approved her murder) from the left-wing LINKE, heir to the SED - the Socialist Unity Party that ruled East Germany until 1990. This division shows how deeply immersed we are in 20th century history, even after more than a hundred years.

But the memory is more complex, even among their devoted followers. Each party selectively chose aspects that served its interests while concealing inconvenient elements.

Consider the DDR, the German Democratic Republic: it elevated Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht to the status of national heroes, naming countless streets, buildings and schools after them. Every child knew their faces and history, and studied Luxemburg's theoretical texts on Marxism - albeit carefully curated ones.

Rosa Luxemburg's writings were not always in line with Soviet or East German ideology. She would probably not have survived Stalin's purges and would have been considered a dissident in the GDR. Although she initially welcomed the October Revolution from prison, she also voiced criticism. Her vision of the revolution centred on giving ordinary people a real voice through free and secret elections. This principle was so strongly expressed by Luxemburg that in East Germany people were arrested simply for displaying one of her most famous quotes on protest signs - a quote you may have seen before:

«Freiheit nur für die Anhänger der Regierung, nur für Mitglieder einer Partei - mögen sie noch so zahlreich sein - ist keine Freiheit. Freiheit ist immer Freiheit der Andersdenkenden, sich zu äußern.»

«Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for members of a party - however numerous they may be - is not freedom. Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters to express themselves.»

And then:

«Nicht wegen des Fanatismus der ‘Gerechtigkeit’, sondern weil all das Belebende, Heilsame und Reinigende der politischen Freiheit an diesem Wesen hängt und seine Wirkung versagt, wenn die ‘Freiheit’ zum Privilegium wird.»

«Not because of fanaticism for 'justice', but because all that is invigorating, healing and purifying in political freedom depends on this essence, and its effect fails when 'freedom' becomes a privilege.»

Various groups of Rosa Luxemburg's formative places and ideas eventually turned against her legacy. Her story is quintessentially European, emerging at a pivotal time when socialist theory transformed into revolutionary action. During this period, other powerful forces —especially nationalism and, in relation to her Jewish background, the rising Zionist movement— were also reshaping the continent.

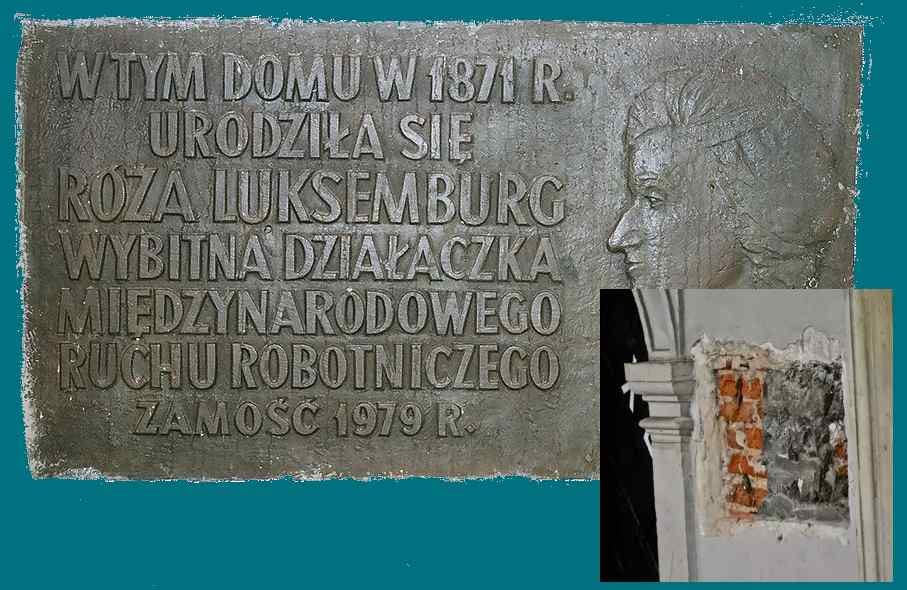

Rosa Luxemburg was born on March 5, 1870 to Jewish parents in Zamość, Poland - a town halfway between Lublin and Lviv. She became involved in socialist causes in her youth and was forced to flee to Switzerland to avoid political persecution and to study at the University. In 1898 she obtained German citizenship through a marriage of convenience. Yet she never forgot her Polish identity and maintained a deep love of Polish culture and her mother tongue.

Politically, however, Luxemburg saw herself first and foremost as an internationalist. During her youth, Poland was divided: her birthplace was in the Polish Congress Republic, a vassal state of the Russian Empire, while other parts belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire or Prussia. Although Luxemburg wrote extensively on the Polish national question, her position was clear: an independent Poland could only come about through socialist revolutions in Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia.

She believed that once the social question was resolved, other issues - autonomy, self-government, state associations - could be resolved peacefully. But she rejected the concept of nations altogether. She saw 19th century nationalism as a bourgeois, conservative construct designed to suppress workers' rights. For her, nations were enemies of peace, instigators of war and oppressors of the masses. She argued that achieving Polish independence through world war would not only be bloody but would also betray the liberating aims of socialism.

This sparked an ongoing conflict with Polish nationalists that continues to this day. In 2018, the (at that time) ruling populist party PiS removed a plaque commemorating Rosa Luxemburg in Zamość. Similarly, the Warsaw Citadel prison - where Luxemburg was imprisoned in 1906 - has numerous plaques honouring political prisoners who fought for Polish independence, but no mention of Luxemburg. Many residents of Zamość admit that they never learned about her at school or in local history. Only recently, through YouTube and podcasts, have many Poles begun to rediscover her legacy, although she remains a controversial figure.

Zamość was also one of the small towns with the largest Jewish presence. Luxemburg's family was influenced by the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment), prosperous, somewhat assimilated, but still attached to their Jewish religious roots.

The relationship between Rosa Luxemburg and her Jewish identity, together with the contemporary question of Zionism, has contributed for decades to making her difficult to interpret.

A self-hating Jew according to some, an anti-Zionist according to others; in reality, one has to enter Rosa's ideal world to understand her relationship with her Jewish roots. To be clear, Rosa Luxemburg never hid her Jewishness, never denied her roots, partly because she couldn't: her party comrades - overtly or latently anti-Semitic - often reminded her of it. In 1903, in the party newspaper Vorwärts, she issued a sharp statement against the «anti-Semitic and xenophobic outbursts» of the comrade who, with his anti-Jewish agitation, was "morally on a par with the Prussian police". In a letter, Rosa also complained: «It's always like that with them. When they're in trouble, help us, Jew! And when the need is over, get out, Jew!»

SEE 2016 Tabletmag: “Actually, Rosa Luxemburg Was Not a Self-Hating Jew”

Like the Polish nationalists, the Zionists saw Luxemburg as a distant, even hostile figure, indifferent to anti-Semitism. This characterisation was wrong: During her Polish childhood and youth, Luxemburg witnessed the terrible conditions of impoverished Jews and was deeply affected by the pogroms. These experiences stayed with her for the rest of her life. But beyond her internationalist stance, she was fundamentally a humanist universalist.

She believed that empathy transcended tribal, geographical or ethnic boundaries - it was inherently human and therefore universal. This perspective is beautifully expressed in one of the most profound texts from her vast collection of letters - more than 2,700 written before, during and after her imprisonment. In a letter to her friend, the German-Jewish socialist and feminist Mathilde Wurm, written on 16 February 1917 from the prison where she was being held as a preventive measure during the First World War, she rejected the notion that Jewish suffering deserved special consideration over other human suffering:

«Was willst Du mit den speziellen Judenschmerzen? Mir sind die armen Opfer der Gummiplantagen in Putumayo, die Neger in Afrika, mit deren Körper die Europäer Fangball spielen, ebenso nahe.» […]

«What do you want with this theme of the “special suffering of the Jews”? The victims of the rubber plantations in Putumayo and the Blacks in Africa, whose bodies the Europeans use as playthings, are just as close to my heart.» […]

This is followed by a quote from a book about the extermination of the Herero by German colonial troops under the command of General Lothar von Trotha in 1904, a military operation now recognised as genocide. Luxemburg goes on to say that the unheard cries of those dying of thirst resonate so strongly in her:

«Sie hallen in mir so stark nach, dass ich keinen Sonderwinkel im Herzen für das Ghetto habe: Ich fühle mich in der ganzen Welt zu Hause, wo es Wolken und Vögel und Menschentränen gibt.»

«They resound with me so strongly that I have no special place in my heart for the ghetto. I feel at home in the entire world, wherever there are clouds and birds and human tears.»

In these lines you'll find one of the reasons why Rosa Luxemburg, despite her complexity, has become the icon she still is today, in our post-ideological, polarised, social media-dependent age.

On the one hand, the rediscovery of her political writings in the 1960s - until then taboo in the West - provided material for the emerging European student movement of '68, making her a kind of female version of Che Guevara - both somehow sanctified by the circumstances of their deaths.

At the same time, the literary discovery of Luxemburg began: thousands of letters in which she often spoke not of politics but of feelings, nature, life and beauty. In flawless, vivid and poetic German prose. It was the written version of the passion she brought to her speeches, which, according to those who heard them, captured not only minds but, above all, hearts. So did her letters. Some collections of her correspondence became bedside reading for teenagers. And many decades later, on social media, they have become memes: those who post them often don't know Rosa Luxemburg's biography, but they publish or share certain phrases - which were not born as aphorisms, but have become them - because they feel deeply evocative. Who doesn't know phrases like

«Wer sich nicht bewegt, spürt seine Fesseln nicht!»

«Those who do not move do not notice their chains»,

or

«Man kann die Menschen nur richtig verstehen, wenn man sie liebt»

«You can only truly understand people if you love them»

In an era when empathy seems increasingly rare, dismissed, and even scorned, these letters radiate exactly that—deep empathy for their recipients, for humanity, for animals, and for the entire universe.

On this January 15th, in Rosa Luxemburg's memory, I share excerpts from one of her letters that Karl Kraus brought to prominence in 1920 through his newspaper "Die Fackel" ("The Torch"), which he introduced with these words:

«Shame and disgrace on any republic that does not include this unique document of humanity and poetry in the German language in its schoolbooks (…) and does not inform the youth growing up in those times, to their horror at the humanity of that era, that the body that enclosed such a noble soul was beaten to death with rifle butts.»

«Schmach und Schande jeder Republik, die dieses im deutschen Sprachgebrauch einzigartige Dokument von Menschlichkeit und Dichtung nicht (…) in ihre Schulbücher aufnimmt und nicht zum Grausen vor der Menschheit dieser Zeit der ihr entwachsenden Jugend mitteilt, dass der Leib, der solch eine hohe Seele umschlossen hat, von Gewehrkolben erschlagen wurde».

The letter describes an experience in the courtyard of the prison where Luxemburg was imprisoned in 1917: a buffalo, requisitioned for 'war service', is being whipped by a soldier. The vivid description of the animal's agony is not only highly poetic, it is also a touching document of humanity and love for animals, probably one of the most powerful, beautiful and sad animal stories in world literature. In the same letter, we find a passionate love of life that is both poignant and radiant. Here it is for you, abbreviated in the middle, but retaining all its splendour:

A letter from Rosa Luxemburg to Sophie Liebknecht written in mid-December 1917.

«Jetzt ist es ein Jahr, daß Karl in Luckau sitzt. Ich habe in diesem Monat oft daran gedacht, und genau vor einem Jahre waren Sie bei mir in Wronke, haben mir den schönen Weihnachtsbaum beschert ... Heuer habe ich mir hier einen besorgen lassen, aber man brachte mir einen ganz schäbigen mit fehlenden Ästen – kein Vergleich mit dem vorjährigen. Ich weiß nicht, wie ich darauf die acht Lichteln anbringe, die ich erstanden habe. Es ist mein drittes Weihnachten im Kittchen, aber nehmen Sie es ja nicht tragisch. Ich bin so ruhig und heiter wie immer».

The German original in its full length, here.

Wroclaw, mid-December 1917.

It's been a year since Karl was in Luckau. I've been thinking about it a lot this month, and it was exactly a year ago that you visited me in Wronke and gave me that beautiful Christmas tree... This year I had one brought here, but they brought me a rather shabby one with missing branches - no comparison with last year's. I don't know how I'm going to put the eight little candles I bought on it. This is my third Christmas in prison, but please don't take it tragically. I remain as calm and cheerful as ever.

Yesterday I lay awake for a long time - I can't fall asleep before one o'clock now, although I have to go to bed at ten - and then I dream of various things in the dark. Yesterday I was thinking: 'How strange it is that I am always in a state of joyful trance - for no particular reason. Here I am, for example, lying in a dark cell on a rock-hard mattress, the house is silent as a graveyard, you feel like you are in a tomb; from the window you can see the reflection on the ceiling of the lantern that burns all night in front of the prison. From time to time you can hear the distant clatter of a passing train, or the throat-clearing of the guard under the window as he takes a few slow steps in his heavy boots to move his stiff legs. The sand crunches so hopelessly under these steps that the whole desolation and hopelessness of existence rings out into the damp, dark night. There I lie, silent and alone, wrapped in these many black cloths of darkness, boredom, bondage and winter - and yet my heart beats with an incomprehensible, unknown inner joy, as if I were walking across a flowering meadow in bright sunshine. And I smile in the darkness of life, as if I knew some magical secret that would prove all evil and sadness wrong and turn everything into pure light and happiness. And yet I search for a reason for this joy, find nothing, and have to smile at myself again.

I believe the secret is nothing more than life itself; the deep darkness of the night is as beautiful and soft as velvet, if only you look at it properly. And in the crunching of the damp sand beneath the slow, heavy steps of the guard, there is also a small, beautiful song of life - if only you know how to listen. It is at moments like these that I think of you, and I would so much like to give you this magic key, so that you too may always, in every situation, perceive the beauty and joy of life, so that you too may live in rapture, and walk as if on a colourful meadow. I don't want to frighten you with asceticism and imaginary pleasures. I give you all real sensual pleasures. I only wish to give you my inexhaustible inner serenity, so that I may be at peace about you, knowing that you go through life wearing a cloak embroidered with stars, which protects you from all that is petty, trivial and frightening.

[…]

Oh, Sonitschka, I felt a sharp pain here; in the courtyard where I walk, military wagons often come, full of sacks or old soldiers' coats and shirts, often stained with blood... which are unloaded here, distributed among the cells, mended, then reloaded and returned to the military. The other day a wagon like this arrived, pulled not by horses but by buffaloes. It was the first time I had seen these animals up close. They are stronger and broader than our cattle, with flat heads and flattened horns, their skulls more like our sheep, all black with big gentle eyes. They come from Romania, trophies of war... The soldiers who drove the wagons said that it was very difficult to capture these wild animals, and even more difficult to use them as labour because they were used to freedom. They were terribly beaten until the words 'vae victis' could be applied to them... There are said to be a hundred of these animals in Breslau alone, and they are now given miserable and meagre fodder, having been used to the lush pastures of Romania. They are ruthlessly exploited to pull all sorts of carts and perish quickly.

A few days ago, a wagon came in loaded with sacks, piled so high that the buffaloes couldn't get over the threshold. The escorting soldier, a brutal fellow, started beating the animals so hard with the thick end of his whip handle that the female guard confronted him indignantly and asked him if he had any compassion for the animals! "No one has pity for us humans either," he replied with an evil smile, and continued to beat them even harder... The animals finally pulled themselves together and made it over the rise, but one was bleeding... Sonitschka, buffalo hide is proverbially thick and tough, but it was torn. The animals then stood completely still and exhausted as they were unloaded, and one, the one that was bleeding, stared ahead with an expression on its black face and soft black eyes like a child who had been crying. It was exactly the expression of a child who has been punished severely and doesn't know what for, why, how to escape the pain and the brutal force... I stood in front of him and the animal looked at me, tears ran down my face - they were his tears, one cannot feel more pain for one's dearest brother than I did in my helplessness at this silent suffering. How far away, how unreachable, how lost were the free, lush, green pastures of Romania! How different the sun shone there, how different the wind blew, how different the beautiful sounds of the birds or the melodious calls of the shepherds. And here - this strange, horrible city, the musty stable, the disgusting, mouldy hay mixed with rotten straw, the strange, horrible people, and - the blows, the blood running from the fresh wound...

Oh, my poor buffalo, my poor beloved brother, we both stand here so helpless and numb, and we are one only in pain, in powerlessness, in longing. - Meanwhile the prisoners bustled about the wagon, unloading the heavy sacks and carrying them into the building; but the soldier, with both hands in his pockets, walked across the yard with large steps, smiling and whistling softly a street tune. And the whole glorious war passed before my eyes...

Sonjuscha, dearest, despite everything stay calm and cheerful. That's how life is and that's how we must take it - bravely, undaunted and smiling - despite everything.

Write quickly, I embrace you, Sonitschka.

Your Rosa.

So ist das Leben und so muß man es nehmen,

tapfer, unverzagt und lächelnd – trotz alledem.

Rosa Luxemburg

BOOKSHELF

Ernst Piper, Rosa Luxemburg: ein Leben, 2021 (DEU)

Kate Evans, Red Rosa: Die Graphic Novel über Rosa Luxemburg, 2022 (ENG)

Share this post