“Die Wiener lieben ihre Träume, aber sie fürchten die Visionäre.” (The Viennese love their dreams, but they fear the visionaries)

Karl Kraus

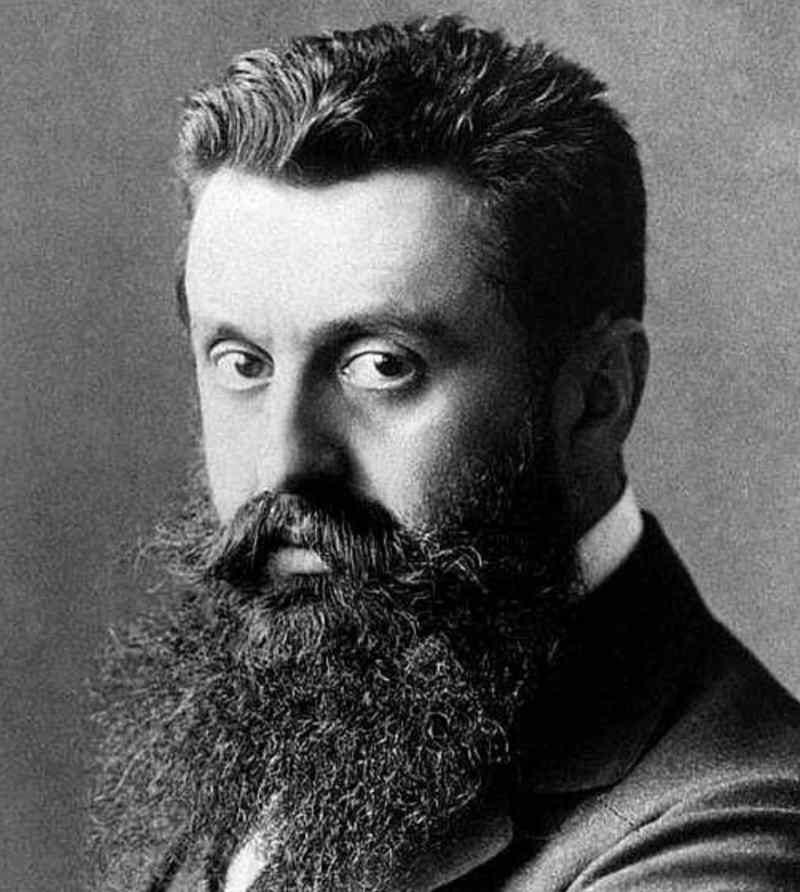

Theodor Herzl is as much a part of the heart of Vienna as Mozart, the Prater, Empress Sisi and Gustav Klimt. His grand vision was a radical response to the Viennese and European anti-Semitism of the late 19th century. But while developing his vision of a new/old home for the Jews and a mass exodus from Europe, Herzl also embraced the best of what the city had to offer. Though politically critical of Vienna, he was culturally in love with it - his dream, before the creation of a Jewish state, was to succeed as a playwright at the Burgtheater. And although he was born in Budapest, Herzl considered himself a true Viennese:

"Ich bin ein Wiener durch und durch" (I am a Viennese through and through).

Theodor Herzl

He was not loved by most Viennese in his time: not by the antisemites, not by the assimilated Jews who considered Zionism a dangerous, self-damaging ideology, nor by the orthodox Jews, who saw Zionism as blasphemous.

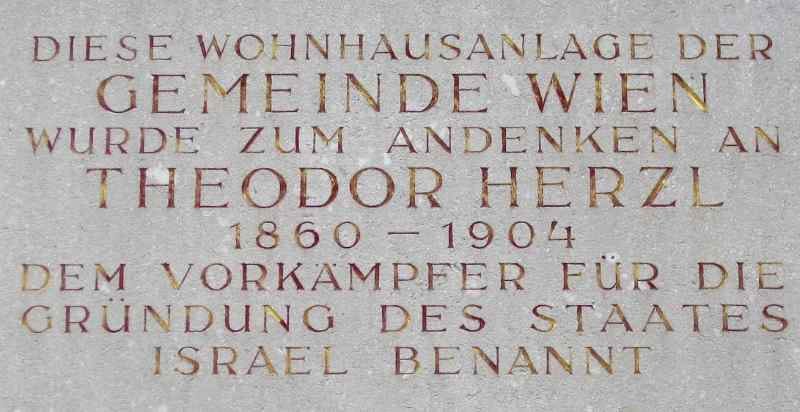

And later? Only in 1960 did the city decide to dedicate a building to him. Then, gradually, memorial plaques appeared here and there —but not in the most visible places, not of substantial size, not always directly connected to his life's milestones. These gestures were enough, however, to soothe the city's institutional conscience.

A new commemorative plaque was installed in September 2023, just weeks before October 7, on the residential building where Herzl lived between 1896 and 1898. The moment was marked by Israel's president Herzog's visit to unveil the plaque and cement a new understanding between Austria and Israel.

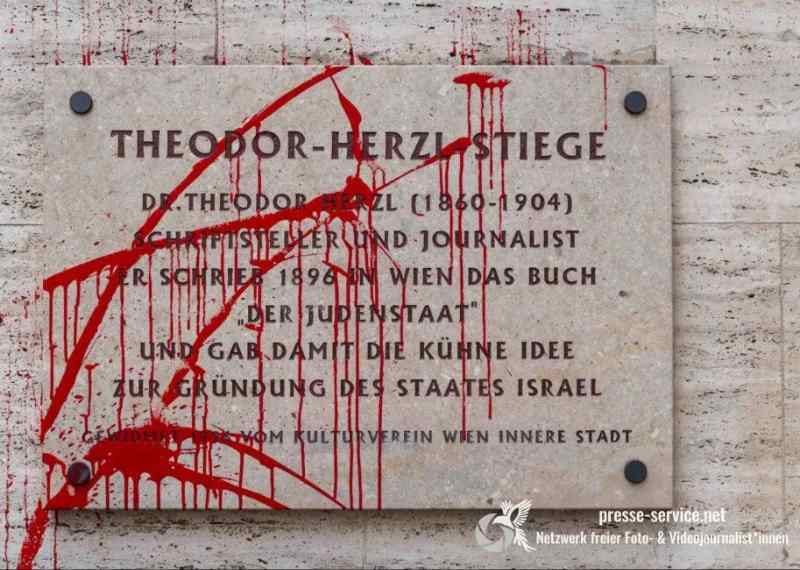

One month later, and again in November 2024, the plaque fell victim to anti-Israeli ink attacks. The question of whether Vienna can live up to its legacy remains open.

A walk through the places where the city remembers Theodor Herzl, as well as the places that were important to him but do not bear his name, reveals something about the dissonances, contradictions and paradoxes of Vienna's relationship with this child whose life was so short and whose afterlife was so great. Join me on this walk.

“In Wien habe ich alles gelernt, was mich geprägt hat – auch die Konflikte.” (In Vienna I learned everything that shaped me - including the conflicts.)

Theodor Herzl

Leopoldstadt 1878-1881

Squeezed between the Donau Canal and the main Danube, lies the district of Leopoldstadt. Nowadays, people go to there either because it's on the way to the Prater or because they're curious about kosher food. While the center of Vienna has one of the richest Israeli culinary scenes in Europe, very hip and contemporary, Leopoldstadt, thanks to its history, offers more traditional cuisine, often with Central Asian influences, strictly kosher. Banned from the inner city, the Jews of Vienna settled here from the mid-1600s, followed over the centuries by those from elsewhere, especially from the eastern part of the Austrian Empire.

Here, in 1878, Theodor Herzl's parents arrived from Budapest, to start a new life in a healthier and more economically attractive place. The neighbourhood was, and still is, predominantly Orthodox, while the Herzl family, though devout and somewhat observant, were decidedly assimilated. The young Herzl had no doubt as to which place he preferred to frequent, the synagogue or the theatre. And in Vienna he found a theatrical paradise: there was even a small theatre in the building where the Herzl family lived for a time, at Praterstrasse 25.

The building at Praterstrasse 25 is beautiful, bourgeois, Jugendstil. It does not have anything in common with the only place in Leopoldstadt that bears Theodor Herzl's name: an anonymous post-war Viennese social housing complex, named after him in 1960: Theodor-Herzl-Hof is six storeys high and overlooks the Karmeliter district, a small neighbourhood that is itself part of Leopoldstadt, famous for its market square (with kiosks where you can eat and drink very well) and for the massive presence of Orthodox Jews.

When, some twenty years later, Herzl became the champion of modern Zionism, the Eastern Orthodox Jews of Leopoldstadt were his first opponents. But who did this Hungarian think he was, the new Messiah? The Talmud had spoken clearly on the matter of Israel: the Jews were not to return to the land of Israel and were not to rise up against the gentiles by force until God Himself sent the Mashiach, the Messiah, indicating that the time was right. And until then they were to stay where they were, be it Austria-Hungary, Germany or the Russian Empire with its pogroms.

The fact that there is not one, but two commemorative plaques here, in remembrance of the fact that the idea of a state in which all Jews would be welcome and protected was stronger than the Talmud, is the first paradox I encounter along this walk.

In the inner city 1882-1891

Theodor's parents invested in his future by sending him to university. And what could be better than studying law? He lived up to their expectations: he studied successfully, even joined a student fraternity—one of those with colorful sashes and sword duels—only to leave it shortly afterwards in disgust, having tasted its deep anti-Semitism.

In 1882, Theodor decided to become independent of his parents and crossed the Danube Canal to the inner city and its theatres, where he believed he could make a better career as a writer than as a Jewish —therefore second-rank— civil servant.

He settled at Kolingasse 13 in the ninth district, near Schottentor. This part of the ninth district is characterized by grand imperial buildings and narrow streets —typical of imperial Vienna outside the Ring. As the city expanded rapidly, buildings were constructed tall and close together, leaving no room for trees. This architectural style has modern consequences: today, the area becomes stifling in summer heat, while in winter, the closely packed buildings create perpetual shadows. We'll revisit this neighborhood later.

In this house, Theodor Herzl lived for over a year before moving to an apartment at Zelinkagasse 11, located in the old city center within the Ring. Then, as now, it wasn't the most desirable area to live —the spaces were quite cramped. In 1884, Herzl earned his doctorate in law and worked at both the Regional Court and Commercial Court in Vienna and later in Salzburg, for some months.

He enjoyed life there, but the lure of Vienna proved irresistible. His ambition was clear: to make a living from writing. He wrote his first play in 1882, followed by another in 1885 - both with the dream of seeing them performed at the Burgtheater, which was (and, if I may say so, still is) the most prestigious German-language theatre. In 1887 he took a job as a columnist for the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung. It wasn't quite the artistic career he had in mind, but it allowed him to write and earn a living.

Back in Vienna, he returned to live with his parents in a new house in Leopoldstadt - at Hollandstraße 1 - almost overlooking the Danube Canal. Herzl let his parents preview everything he wrote: articles, plays, comedies. Which is certainly sweet, except that Mum and Dad would have preferred him to work as a lawyer. And, like all parents, perhaps married and settled down asap.

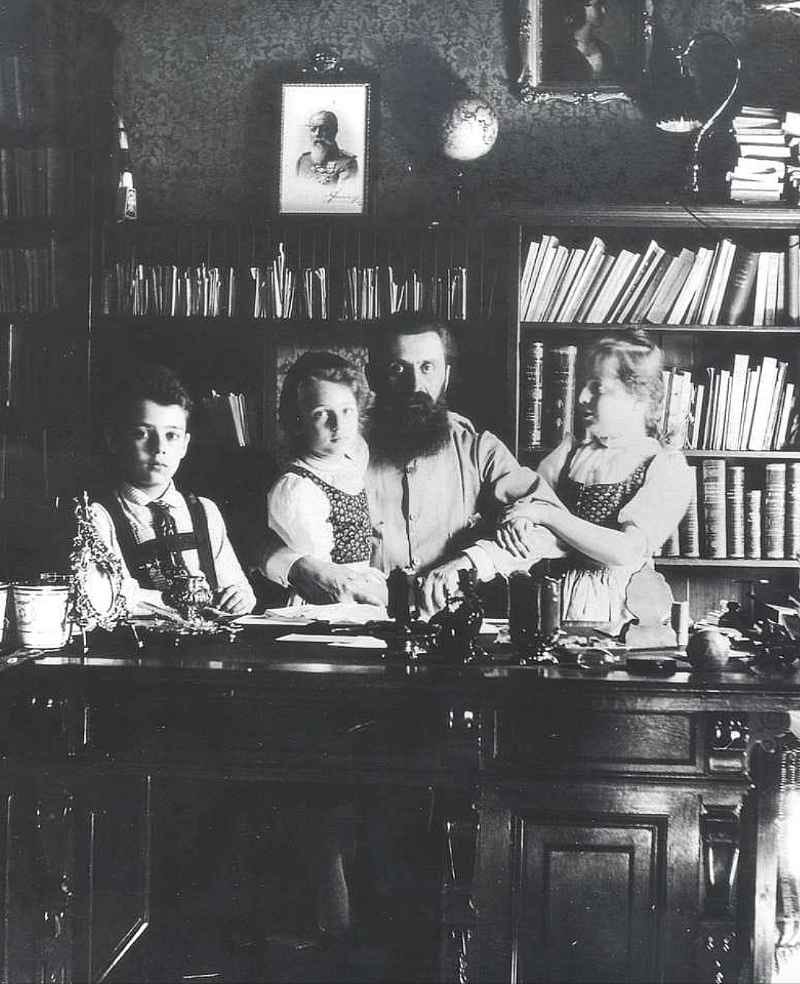

In 1889, two important things happened in Herzl's life: after a series of theatrical successes in Prague and Germany, one of his comedies finally made it to the Burgtheater; the second was his marriage to 19-year-old Julie Naschauer, a girl from a good family with a rich dowry. After a long honeymoon, the couple returned to Vienna and settled in the inner city, in an apartment at Marc-Aurel-Straße 7.

Between 1882 and 1891 the Jewish question, though present in Viennese social life, was not prominent in Herzl's work or in his private life. During this period his attention was focused on his troubled personal affairs. As his family grew - with two children born in 1890 and 1891 - his domestic life was turbulent. His wife's unstable mental health led to frequent outbursts and threats of suicide, creating a fractured home environment. It was partly to escape this oppressive atmosphere that Herzl accepted a position as Paris correspondent for the Neue Freie Presse in late July 1891.

What traces of Theodor Herzl's life as a journalist and budding playwright remain in the inner city? Well, following his footsteps in the inner city of Vienna is like a Sherlock Holmes investigation. Only one place commemorates him, connected to his residence at Marc-Aurel-Straße 7: in 1996, on the 100th anniversary of the publication of Der Judenstaat, a small, modest staircase connecting Marc-Aurel-Straße to the narrow, dark Sterngasse was renamed Herzl-Stiege. The locals call it the "Vienna Bermuda Triangle" because of its obscure location, which most passers-by miss. But not the vandals who, armed with Google Maps, found their way there in December 2024 with the deliberate intention of targeting Herzl wherever his presence was marked.

Back from Paris 1895 - 1897

For many, Paris is where the story of modern Zionism begins. It was there that Herzl, who was more inclined to enjoy the Parisian cultural scene, encountered intense French anti-Semitism and witnessed the Dreyfus trial in December 1894, in which the accused was clearly condemned because of his Jewish identity. Had the Dreyfus affair remained an isolated climax of a social wave that ebbed and flowed, Herzl would probably not have had the impetus to pursue the idea of a new state for the Jews.

But when he returned from Paris and took a new flat in Alsegrund —in Pelikangasse 16— also in the 9th district, Vienna greeted him with a political earthquake: in the autumn of 1895 Karl Lueger was elected mayor of Vienna by a large majority.

Lueger was a virulent xenophobe, anti-liberal and anti-Semitic: he captured the sentiments of the native Viennese who could not keep pace with the explosive growth of the city - now a multiethnic metropolis, an evolution that many did not accept. Lueger ran an election campaign that focused entirely on the old and new enemies of the common people: Jews, Hungarians, liberals. Emperor Franz Joseph I repeatedly refused to confirm Lueger as mayor. It was only after another round of voting in November 1895 that Lueger was appointed, to serve until his death in 1910, when Vienna became a stronghold of open anti-Semitism in its most aggressive form.

In antisemitic Vienna between 1906 and 1913, a young aspiring artist —penniless and at times homeless— spent his time walking along the Ring and surrounding parks. Here, Adolf Hitler found his ideal inspiration and became an open admirer of Mayor Karl Lueger.

Herzl sensed that Vienna was heading down a dangerous path. The free press should have publicly addressed these warning signs, but remained silent. By fall 1893, Herzl had already discussed the Jewish question with editors at the "Neue Freie Presse," but they refused to engage— fearing identification as a Jewish newspaper. They consistently downplayed his reports, even those from Paris about the Dreyfus affair. Most notably, they censored Herzl's account of Dreyfus's public degradation, removing his description of the crowd's shouting not only "Death to the traitor" but also "à mort! à mort les juifs!", “death to the Jews!”.

Frustrated by his own newsroom, Herzl decided to act alone. Without any leadership position or movement behind him, he approached influential figures —wealthy Jews, philanthropists— to discuss what he identified as the Judenfrage, the jewish question. His efforts proved futile. His ideas threatened those who had carefully built their positions in European society, accumulated wealth, forged political connections, and earned noble titles. The hypocrisy was evident: Mayor Karl Lueger himself would dine with Jewish bankers and wealthy merchants after delivering his anti-Semitic speeches, and when confronted about this inconsistency, he would simply declare:

"Wer ein Jud ist, das bestimme ich”

”Who is a Jew, I decide."

Faced with this hostile climate and mounting frustration, Herzl turned to what he knew best: writing. In his study at Pelikangasse, he wrote feverishly for several weeks, transforming what was initially meant to be a letter to the Rothschilds into a manifesto for all: “Der Judenstaat”, The Jewish State. By mid-1895, he had completed the draft. All that remained was finding a publisher —his cautious employer, the "Neue Freie Presse," was clearly not an option.

Today, 400 meters from the newspaper's former headquarters at Fichtegasse 9-11, there is a small square facing the Stadtpark and the eastern section of the Ring. Narrow and surrounded by hotels, it's merely a passage to the underground parking beneath. It's named Theodor-Herzl-Platz since 2004, but when passing through one hardly notices this.

It leaves a bitter taste when one considers that the western section of the Ring —its most beautiful part, featuring the old University— bore Karl Lueger's name until 2012. When it was finally renamed Universitätsring after twelve years, some wondered if it wouldn't have been more fitting, even poetic, to honor Theodor Herzl's memory there instead. Others, however, protested the removal: these were the far-right represented by the FPÖ party, which is now, in 2024, Austria's most popular party with 28.8% of votes in the last federal elections and—at the time of writing—asserting their right to appoint the new Austrian chancellor.

Here it is, this square: this too was desecrated just over a month ago:

New life, new home 1896-1898

We are still in the ninth district, where, within a few hundred meters of each other, we find three significant locations: the Herzl family's new residence on Berggasse 6; the publishing house on Währinger Strasse 5, where —at Herzl's own expense— the first edition of Der Judenstaat was published; and around the corner Türkenstrasse 9, where from 1898, Herzl established himself as both a newspaper publisher and the leader of the Zionist movement. Sigmund Freud's home and practice was also located on Berggasse. But let's take it one step at a time.

"The Jewish State" was published in February 1896, with an initial print run of 3,000 copies. Herzl's feelings about the work were mixed. In his diaries, he wrote "Now I feel relief that the work is done. I don't expect any success." The publicist Saul Raphael Landau, a Viennese from Krakow and already a convinced Zionist, read the book and had the opposite opinion:

"The bomb has exploded. They tried to prevent it - in vain. It had to happen".

The text —which stunned many with its bold declaration to European Jews that "we are one people, one people" (not merely religious groups or scattered communities)— also provided detailed practical plans for establishing organizations and building relationships to create a Jewish state. As it circulated from person to person, it sparked an immediate and widespread response. Within weeks, translations appeared in seven languages.

Life at home in Berggasse could not be peaceful, both for family reasons - Herzl's was not a happy marriage - and because readers would come to comment, discuss and understand what this little book would lead to in practice. Visitors came from all over the world: "The road from Paris to Palestine begins in my room," he wrote on 6 January 1897.

At this point, Herzl had to ask himself what to do next. When his newspaper, the Neue Freie Presse, dismissed "The Jewish State" as unworthy of attention, he resolved to establish his own publication.

He launched "Die Welt" (The World) on June 4, 1897, from Rembrandtstraße 11. This new venture was more than just a newspaper; it was a project of visibility. But a newspaper alone would not be enough. All the people who came to visit him, all those who wrote to him, all those who were inspired and wanted to do something with this paper project, had to be brought together to understand how to proceed. But in Vienna it seemed impossible to organise a Zionist congress: the hostility of the Jewish world of every stripe - assimilationist bourgeois, socialist, orthodox - made it impossible.

The famous First Basel Congress of 1897 was a hastily organised Plan B. But it was a resounding success, after which Herzl wrote:

"If I were to sum up the Basel Congress in one word, which I shall be very careful not to do publicly, it would be this. At Basel I founded the Jewish State. If I said that out loud today, I would be greeted by universal laughter. Perhaps in five years, and certainly in 50, everyone will admit it".

A success, indeed, but not in Vienna, where on his return Theodor Herzl was surrounded by laughter - in the editorial offices of the Neue Freie Presse, in the theatre, in the coffeehouses. He shared the fate of Vienna's visionaries, misunderstood as they were, like Sigmund Freud.

"No prophet is accepted in his own country," or "Nemo Propheta in Patria," as the Latin saying goes. While the Viennese were booing him, Mark Twain, after seeing Herzl's play "The New Ghetto" —written even before the Dreyfus trial— was so enthusiastic that he immediately began translating the drama. Sigmund Freud, Herzl's neighbor at Berggasse 19, also saw "The New Ghetto." The play inspired Freud to dream one night about the Jewish question, and later, on September 28, 1902, he wrote a letter to the founder of modern Zionism, enclosing a complimentary copy of his book "The Interpretation of Dreams":

"Dear Doctor, on the recommendation of your colleague, the editor Mr. M., I've taken the liberty of sending you a copy of my book on the interpretation of dreams, published in 1900, together with a short lecture on the subject. I don't know whether you will agree with Mr. M., but I ask you to keep it as a token of my esteem for you, which I, like many others, feel for the poet and fighter for the human rights of our people. Yours, Prof. Doc. Freud".

As Herzl traveled across Europe to convince authorities and power centers of his cause, he realized he could not manage "Die Welt" alone while ensuring its financial sustainability. He secured both a new location at Türkenstrasse 9 in the same neighborhood and appointed the young, talented Martin Buber as Editor in Chief. Buber assumed the role in September 1901 but resigned a year later, as the first divisions within the Zionist movement began to surface.

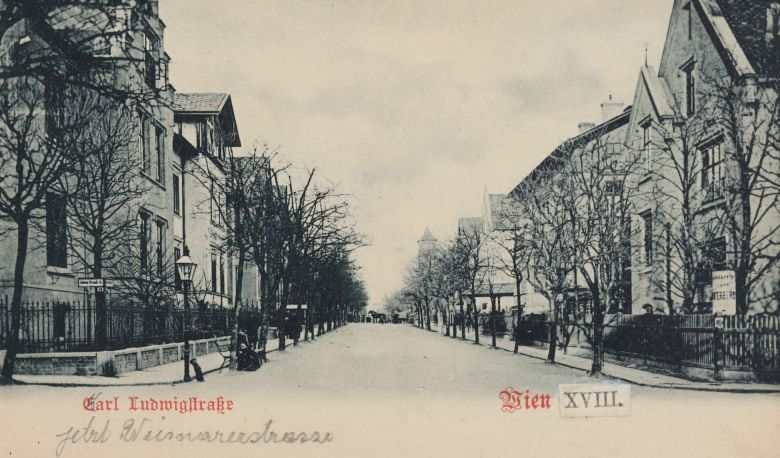

Palestine and Back: Envisioning the Old New Land, 1898–1903

In an attempt to improve his family's health—his wife and daughter were sickly, and Herzl himself suffered from a heart weakened by an old infection—Theodor moved in 1898 to the Währing district's Cottageviertel. This beautiful area featured spacious, garden-surrounded houses with large apartments amid lush greenery. For three years, from May 1898 to May 1901, the family lived at 68 Weimarer Strasse. Here, Herzl established a routine of morning bicycle rides before attending to his editorial and political work. His life and health seemed to be improving at last, becoming more relaxed—but this was merely an illusion.

In autumn 1898, Herzl made his first journey to Palestine. He arrived in Jaffa on October 26, and two days later reached Jerusalem to meet German Kaiser Wilhelm and seek his support with the Ottomans. While the journey proved a political failure, it profoundly moved Herzl as he encountered firsthand the complex reality of Turkish Palestine—a world of misery and contradictions, yet also of deep humanity. The physical toll of the journey was severe, leaving him completely exhausted. Upon returning to Vienna, he felt his strength had been depleted.

Two years later, he secured a meeting with the Sultan in Constantinople, but like Kaiser Wilhelm, the Sultan showed little interest in discussing Zionism. At the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel (December 26-30, 1901), which Herzl chaired, a significant development occurred—the establishment of the Jewish National Fund. This fund would become crucial to the Zionist movement by financing land purchases in Palestine.

During this period, the family also relocated within the Währing district to an elegant apartment at Haizingergasse 29, which would become Herzl's final residence.

It was in this house that Theodor sat at his desk to write a new book, this time a novel. Altneuland, published in 1902, is a utopian novel about a Jewish state. In it, Herzl envisions the Palestine of 1923: a thriving landscape where people of different religions live together in harmony, creating economic prosperity and a global cultural destination - a progressive, Middle Eastern version of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. "New Judea should rule only by the spirit," wrote Theodor Herzl, envisioning a demilitarised zone where all people could live in peace.

In Haizingergasse in 1903, Herzl learned of the Kishinev pogrom in Russia (now Chisinau, Moldova). The massacre's worldwide impact—it was the first pogrom fully documented by international press with photographs—moved Herzl to write directly to Tsar Nicholas II. He sought to win the Tsar's support for the Zionist cause, presenting it as a solution to the Jewish presence in the Russian Empire. Though increasingly frail, Herzl achieved a crucial breakthrough in August 1903 when Great Britain pledged its support for a Jewish state, with future Prime Minister David Lloyd George acting as Herzl's lawyer during the negotiations.

At home, knowing he might not live to see a Jewish state, Herzl purchased a family plot at the Döblinger cemetery in northern Währing. In his diary, he noted this would be only temporary—his body would await transfer to Eretz Israel. This wish was fulfilled in 1949.

The final days, 1904

On 25 January 1904, Pope Pius X granted Theodor Herzl a 25-minute audience in which he explained his opposition to the return of the Jews to Palestine: "The soil of Jerusalem, if it was not always holy, was sanctified by the life of Jesus Christ. [The Jews did not recognise our Lord, therefore we cannot recognise the Jewish people" (diary entry of 26 January 1904, originally in Italian: Noi non possiamo favorire questo movimento...).

Back in Vienna, Theodor Herzl's health deteriorated rapidly. He was visibly exhausted, his heart growing weaker. In his book "Die Welt von Gestern" (The World of Yesterday) Stefan Zweig recounts his final encounter with Herzl in early 1904:

[…] Of all the encounters, only one remains important and unforgettable to me—perhaps because it was the last. I had been abroad, connected to Vienna only through correspondence, when one day I finally met him in the city park. He was clearly coming from the newspaper office, walking slowly and slightly hunched over, having lost his once-springy step. I greeted him politely without stopping, but he straightened up at once and approached me […]

The conversation takes on a bitter tone:

He then spoke with great bitterness of Vienna, where he had found the strongest obstacles, so much so that, if new impulses had not come from outside, especially from the East and also from America, he would already have felt tired. "My mistake," he added, "was to have started too late. […] If you only knew how I suffer thinking about the lost years, with the regret of not having undertaken my task earlier. If my health were as good as my will, everything would be fine, but the years cannot be bought back." I accompanied him for a good stretch to his house: "Why don't you ever come to see me? You have never been to my house. Call me first and I will always find time."

Zweig did not visit him. In May 1904, following a medical consultation, Herzl traveled to Edlach—a thermal resort halfway between Vienna and Graz—where he stayed twice, in May and June. He died there a few weeks later, on July 3, 1904.

Stefan Zweig recalls the day of Herzl's funeral on July 7, 1904:

It was a strange, unforgettable July day for those who lived through it. From every station in the city, by trains day and night, crowds of Western and Eastern Jews, Russians and Turks poured in from all countries.

They rushed in from provinces and villages, the shock of the news still visible on their faces. In that moment, one could clearly see what countless disputes and words had concealed—a leader of a great movement was descending into the grave. The endless procession made Vienna realize that this was no ordinary writer or poet who had died, but one of those rare shapers of ideas who emerge victorious over a country and people perhaps once in a generation. At the cemetery, chaos erupted as people crowded around his coffin—crying, moaning, and screaming in wild, desperate outbursts. All order dissolved into a primal, ecstatic mourning unlike anything I had witnessed at a funeral before or since. Through this unprecedented grief, erupting from the depths of an entire people, I finally grasped how much passion and hope this solitary man had launched into the world through the force of his thought.

"Die Welt" reported six thousand participants—never before had a Jew received such a funeral.

Three days later, on July 10, 1904, the Zionist Action Committee organized a memorial service in the Wiener Musikverein, the concert hall famous for its New Year's concert. The XI Zionist Congress convened in the same building in September 1913. Among the participants was Franz Kafka, who attended more out of curiosity than belief. Like most assimilated Jews, he maintained his skepticism toward Zionism.

When WWI erupted, many Jews enthusiastically joined the ranks of their armies—in Austria as in Germany—hoping to prove their loyalty to the European Empires and shed their Jewish identity. The rest is history as we know it: tragic, complex, and full of contradictions, yet also the story of an impossible dream that became reality, albeit with many ambiguities.

Would Theodor Herzl feel comfortable in today's Israel? He loved the German language, even envisioning it as the language of the Jewish State. He cherished Viennese culture and its refined manners, which seem ill-suited to the Middle East. But above all, he dreamed of a safe place where Jews could freely choose whether to live there, knowing they would never face the threat of pogroms. He dreamed of a place of peace and progress. His dream is still in the making. This dream took shape in the streets of Vienna.

“In Wien bin ich aufgewachsen mit der Ahnung, dass die Judenfrage nicht nur eine soziale, sondern eine nationale Frage ist.”

"In Vienna, I grew up with the realization that the Jewish question was not only a social issue but a national one."

Theodor Herzl

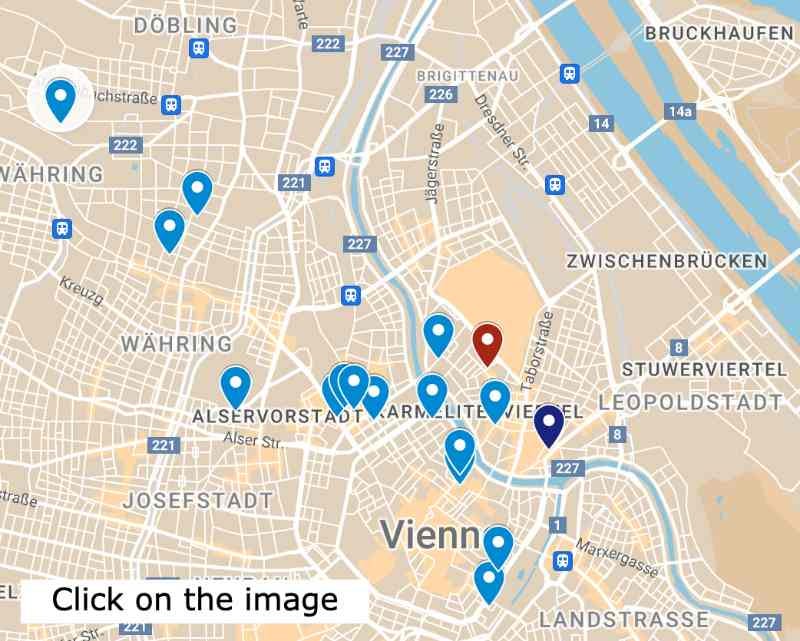

P.S. Vienna's tourist industry is impressive. While it offers several walking tours of Jewish Vienna, there isn't a dedicated Theodor Herzl tour. I've created a simple Google Map marking all the locations mentioned in this post. Here:

Deep links: where to go from here?

🎞️ The Life of Theodor Herzl

It Is No Dream: The Life of Theodor Herzl (2012) is a jewel: narrated by Ben Kingsley and featuring Christoph Waltz, it takes one hour and a half of your time, well spent.

🎙️Unpacking Israeli History: History of Zionism.

Unpacking Israeli History is one of my favorite podcasts. Noam Weissman is a passionate educator whose enthusiasm radiates through each episode, with a voice that captivates listeners throughout. In this episode, Noam explores the Uganda Plan, revealing why Zionist leaders considered alternatives to the Promised Land amid the era's pervasive antisemitism.

In this two-part series, Noam Weissman and Haviv Rettig Gur explore the roots and core principles of Zionism. They unpack its true meaning, trace its origins, and examine its pivotal role in the Jewish narrative.

🗒️ On Substack

If I hadn't discovered Israel from Inside, I wouldn't have stayed on Substack for so long or found it so satisfying. In an era of superficial journalism and social feeds filled with empty statements rather than real experience, finding genuine insider perspectives is like searching for a needle in a haystack. Fortunately, Substack is full of these needles, and it's a well-curated haystack. Israel from Inside stands as Israel's most popular Substack publication.

Share this post