“Where was your family when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed?”

If you ask this question to someone from Eastern Europe, you’ll almost always get an answer—sometimes brief, sometimes deeply detailed. Delve a little deeper, and you might uncover poignant, personal stories that reveal the deep scars left by World War II.

But pose the same question to someone from Italy, France, Spain, or even a German from Düsseldorf, and you’re likely to be met with vague responses or perhaps just a blank stare. Why? In Western Europe, the memory and significance of this pact are often blurred, if not entirely forgotten.

This striking contrast lies at the heart of a new Berlin exhibition—one that’s traveled from Düsseldorf and is set to make its way to Chernivtsi, Ukraine, later this year. In the opening area, a large map of Europe invites visitors to pin their memories of the infamous Hitler-Stalin pact. The result? Eastern Europe is a patchwork of overlapping notes, while the West remains largely empty.

But this exhibition isn’t just about revisiting history. It’s much more—about understanding how the memory of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact has evolved and how it’s remembered differently across time and place. These fragmented recollections continue to shape our still unfinished European identity.

Unequal Memories.

Even today, the shadow of the Hitler-Stalin Pact continues to divide Europe’s collective memory.

In Western Europe, it’s often viewed as just another step toward the inevitable outbreak of World War II—a conflict primarily triggered by Nazi Germany. But for the nations of Central and Eastern Europe, August 23rd—the day the Pact was signed—marks a moment that profoundly altered their history. It’s a moment that still echoes powerfully today, especially against the backdrop of Russia’s ongoing aggression in Ukraine.

For these countries, the Hitler-Stalin Pact wasn’t just a precursor to the war—it was the catalyst. They see it as an agreement that places equal blame on both Germany and the Soviet Union.

Germany’s collective memory, which often casts the country as a “world champion of guilt” while downplaying the roles of other actors, exemplifies how the Pact has been selectively remembered—or, rather, forgotten.

For decades, historical reflection in Germany focused intensely on the Holocaust and the Nazi regime’s war of extermination, with German SS and soldiers cast as the primary villains. Stalin’s role in triggering the war, and the crimes committed by the Red Army, were largely overlooked.

And this perspective wasn’t limited to Germany alone. Much of Western Europe adopted a similar view, partly to avoid any dilution of German responsibility.

Historian Roger Moorhouse, author of The Devil’s Alliance: Hitler’s Pact with Stalin, offered a pointed critique in 2014:

"The Pact still barely features in Western narratives—often relegated to a single paragraph, dismissed as an outlier, a dubious anomaly, or a mere footnote in the broader historical context. Its significance is routinely downplayed to that of the final diplomatic maneuver before war broke out, with no acknowledgment of the ominous Great Power alliance it fostered."

See also: Alex Webber, Poland’s fate is sealed: the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact 85-years on, Telewizja Polska.

The Pact and its secrets.

What exactly was the Hitler-Stalin Pact, and how did the Western world react when the news broke? What did the media have to say at the time?

On August 23, 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union shocked the world by signing a non-aggression pact. Officially, it was an agreement that neither country would attack the other or assist a third party that might do so. On the surface, it seemed straightforward—a mutual promise of peace between two unlikely partners. But there was much more beneath the surface.

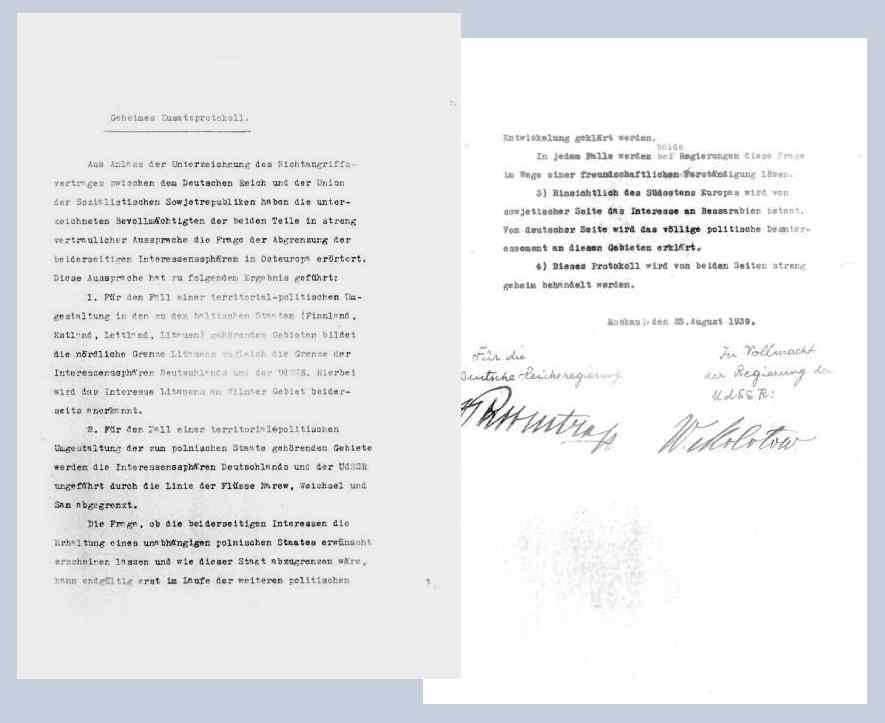

The pact had two parts: one public and one secret. The public part was what everyone saw—a non-aggression pact that appeared to be a sensible diplomatic move. But then there was the secret part, the real game changer. The secret protocol divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

Estonia, Latvia, and Bessarabia were given to the Soviets, while Poland was to be split down the middle along the Narev, Vistula, and San rivers. The language was formal, but the intention was clear: the two powers had agreed to carve up Poland.

The secret protocol reads:

In the event of territorial-political reorganization of the districts making up the Baltic states (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), the northern border of Lithuania is simultaneously the border of the spheres of interest of Germany and the USSR. The interests of Lithuania with respect to the Vilnius district are recognized by both sides.

In the event of territorial-political reorganization of the districts making up the Polish Republic, the border of the spheres of interest of Germany and the USSR will run approximately along the Pisa, Narew, Vistula, and San rivers.

The question of whether it is in the (signatories') mutual interest to preserve the independent Polish State and what the borders of that state will be can be ascertained conclusively only in the course of future political development.

The language was formal, but the substance was clear: both sides had agreed to divide Poland.

It’s a difficult scenario to grasp, but try to put yourself in Stalin’s shoes. From his perspective, Germany’s offer was unbeatable—what we might call today "an offer you can’t refuse." Hitler was offering Stalin massive territorial gains, something the British and French—who were also in negotiations with the Kremlin—simply couldn’t match. Germany was quicker, shrewder, and more pragmatic.

On the afternoon of August 23, Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister, landed in Moscow after flying in from Salzburg. He received a grand welcome with full military honors, including Nazi banners that had been hastily borrowed from a film set. The German delegation was then escorted to the Kremlin, where Stalin himself—in a rare public appearance that underscored the gravity of the moment—greeted them personally.

After the signatures were inked, the event was marked with toasts at a formal banquet. The following morning, Ribbentrop returned to Germany, where Hitler hailed him as "the new Bismarck." With these actions, history had been set on an irrevocable path.

When news of the Hitler-Stalin Pact broke on August 23, 1939, the world was stunned. It was a moment of sheer disbelief—how could two ideologically opposed regimes suddenly decide to join forces?

Shockwaves rippled through the international media, with reactions ranging from astonishment to outright alarm. American journalist John Gunther, who was in Moscow at the time, captured the mood perfectly when he wrote that "nothing more unbelievable could be imagined." What began as disbelief quickly turned into a sense of dread.

Depending on where you were and what newspaper you picked up, the reaction varied widely. In the US and Britain, the mainstream media condemned the pact as a dangerous and cynical move.

But some publications, like the *Daily Worker*, which followed the Communist Party line dictated by the Comintern, struck a very different tone. They hailed the pact as "a victory for peace and socialism—against the war plans of fascism and the pro-fascist policies of Chamberlain." Suddenly, Hitler, who had been the ultimate enemy, was being praised by British and American Communists—at least in these publications—as someone who supposedly wanted peace. It’s a classic example of how propaganda works, both then and now—rapidly changing narratives in the hope that readers would conveniently forget what they had read the day before.

But did anyone suspect that there was more to this already alarming public pact? On 25 August, the Guardian Diplomatic Correspondent wrote:

London, Friday. It is more and more evident that the Russo-German Pact has far greater significance than the published terms imply, though even they would be significant enough. There is a growing belief that, as was suggested in these columns yesterday, Germany and Russia have agreed on the partition of Poland and that the Baltic States are to be a Russian sphere of influence.

On 29 August 1939, the New York Times reported from Montreal, Canada, that American professor Samuel N. Harper of the University of Chicago had publicly stated his belief that "the Russo-German non-aggression pact conceals an agreement whereby Russia and Germany may have planned spheres of influence in Eastern Europe". The next day, on 30 August 1939, the New York Times reported a Soviet build-up on its western frontiers with the transfer of 200,000 troops from the Far East.

From the Wall of Memories in the Museum Berlin-Karlshorst:

I, Natalie, am a descendant of refugees from the Königsberg region of East Prussia on the one hand, and displaced persons from Krasna in the Akkerman district of Bessarabia on the other. The Hitler-Stalin Pact forced my grandparents to move - first to a camp in the Warthegau, then to Rostock, and finally to the Vordereifel region, where many Bessarabian Germans found a new home. Genealogy has always kept us connected to our old homeland and has shaped the actions and existence of our young family.

The Pact and Poland.

Poland was the first victim of the Hitler-Stalin Pact. Poland, a nation reborn in 1918 after a century of foreign rule, had finally regained its independence. However, its borders were a patchwork drawn up by the major powers after World War I. The country was home not just to Poles, but also to significant populations of Lithuanians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, and many Germans.

In 1926, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, a charismatic leader, seized power in a coup. A nationalist at heart, Piłsudski was not a friend to minorities, and their rights were increasingly trampled under his rule. This repression gave both Germany and the Soviet Union a convenient excuse to stir up trouble and eventually justify their invasions.

The world was already on edge. Just a week after the infamous Pact was signed, Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Despite some concerns, the attack still took Poland by surprise. The nation had placed its hopes on military intervention from its allies, France and Britain. Although both countries quickly declared war on Germany, they failed to take immediate action.

Those security guarantees and war declarations turned out to be just words on paper. This experience taught Eastern Europe a harsh lesson: Western promises mean little without tangible military support - weapons and boots on the ground.

Then, on September 17th, the Red Army marched in from the east—without any declaration of war. The Soviets claimed they were "protecting" the Belarusians and Ukrainians, but it was clear—they were seizing their share of Poland. The Polish army, already engaged with the Germans in the west, was blindsided by this second assault. The Polish High Command, realizing the situation was hopeless, ordered their troops to stand down and escape to neighboring countries. The leaders themselves fled to Romania, Hungary, and Lithuania.

In the Soviet-occupied territories, sham elections were quickly organized, leading to the installation of pro-Soviet governments. By November 1939, these areas were annexed by the Belarusian and Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republics. Meanwhile, within just four weeks, Germany had secured and consolidated its gains in western and central Poland.

What followed was a chapter of history we know all too well: annihilation, genocide, and lands soaked in blood. And throughout it all, a twisted, manipulated memory that has been struggling to uncover the truth.

In Poland, every child knows this date. The Hitler-Stalin Pact is etched into the national memory as the "fourth partition," following the three that divided Poland at the end of the 18th century.

However, it took time for this date to become central to Poland's collective memory. During the communist era, discussing the Pact was taboo. It was a forbidden topic, deliberately kept out of public discourse.

Meanwhile, in the Soviet republics of Belarus and Ukraine, the narrative was entirely different.

There, the Pact was portrayed as a glorious "reunification," a step towards bringing territories back together. Belarus has stubbornly held on to that narrative ever since. Even in the early 1990s, when Russia under Boris Yeltsin briefly acknowledged its role in atrocities like the mass murder of Polish elites in Katyn in 1940, Belarus did not shift its stance. In fact, the country doubled down on it.

As recently as 2021, President Alexander Lukashenko declared September 17th—the day the Soviets invaded Poland—as National Unity Day. This day is meant to celebrate the supposed reunification of Western and Eastern Belarus, a tradition that began in 1949 but was later dropped out of respect for their socialist neighbors in Poland. When Lukashenko revived National Unity Day, Poland's Ministry of Foreign Affairs strongly protested, condemning it as "the glorification of Soviet heritage and an attempt to cut Belarus off from its true roots."

Ukraine, instead, has undergone a significant shift since Russia's invasion of Crimea in 2014. The country has completely abandoned the old Soviet narrative. Today, Ukraine recognizes the Pact for what it truly was: the spark that ignited World War II, with equal blame placed on both Stalin and Hitler.

From the Wall of Memories in the Museum Berlin-Karlshorst:

My grandparents married in autumn 1939. They lived in a village just kilometers from the Poland-Soviet Union border along the Zbruch River. Throughout their lives, they experienced several regime and border changes—Ukraine, Poland, Germany, and the Soviet Union. These shifting boundaries had a profound personal impact on them.

The Pact and the Baltic states.

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania emerged as independent countries after World War I, a time of hope and new beginnings. They established democratic systems, embraced their cultural identities, and saw their economies begin to flourish.

But then came the Great Depression in 1929, which abruptly halted the progress of democracy in the region. Lithuania had already veered into authoritarianism with a military coup in 1926. By 1934, similar coups in Estonia and Latvia had dismantled their parliaments, replacing them with authoritarian presidential systems that effectively stripped away minority rights.

In an effort to secure their independence, Estonia and Latvia moved closer to Germany, while Lithuania sought protection from the Soviet Union.

In September 1939 the Soviet Union has just annexed eastern Poland. They turn to Lithuania and say, "Remember Vilnius? The city you've longed for and considered yours for centuries? It's yours now!" But there’s a catch: Lithuania had to allow 20,000 Soviet soldiers to be stationed within its borders, further binding the country to the Soviet Union. It was more or less a Trojan horse.

And then came the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact...

“In the event of territorial-political reorganization of the districts making up the Baltic states (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), the northern border of Lithuania is simultaneously the border of the spheres of interest of Germany and the USSR…”

In essence, Hitler handed over Latvia, Estonia, and eventually Lithuania to Stalin.

The Soviet Union moved quickly, forcing these countries to sign agreements and stationing troops there by the end of 1939. By the summer of 1940, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania found themselves unwillingly absorbed into the Soviet Union as Socialist Soviet Republics.

What followed was a grim period known as the "Russian Year" of 1940-41, which left deep scars on the collective memory of the Baltic people. The brutal Soviet occupation from 1944/45 to 1990/91 further suppressed their culture, language, and identity, as if Moscow was trying to erase everything that made these nations unique.

Meanwhile, West Germany was too preoccupied with its own war crimes to challenge what was happening in the Baltics after the WWII. However, the USA never recognized the annexation.

August 23, 1989: over 2 million people joined hands, forming a human chain that stretched 670 kilometers from Vilnius to Tallinn. Known as the Baltic Way, it was a powerful statement. With their own anthem and the rallying cry "The Balts are rising!" they waved their forbidden national flags and demanded independence.

This was more than just a protest; it was a bold reminder to the world of what that day—the anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—truly meant. The Soviet Union had spent decades denying the existence of this secret pact, but by December 1989, they finally admitted the truth.

It was the beginning of the end. The dominoes began to fall, and soon Soviet rule in the Baltics—and the Soviet Union itself—collapsed.

From the Wall of Memories in the Museum Berlin-Karlshorst:

My father was born in Latvia in 1930. The family left Latvia, where they ran a small fishing boat, under the "Heim ins Reich" agreement were resettled in the Warthegau, now Poland. My father was soon conscripted as a german soldier at Babi Yar, in Ukraine. My sisters were sent to the Baltic islands; three of them returned from captivity in the Soviet army, often thanks to the dense forests. Two managed to escape. They then survived the death march from Königsberg westwards through Poland to Germany.

The Pact and Finland.

For a long time, Finland was a Grand Duchy under the Russian Empire. But as Russia began to crumble, Finland seized the moment and declared its independence in December 1917.

However, deep social and economic tensions soon erupted, leading to a brutal civil war in early 1918. On one side were the "Whites," supporting the elected government, and on the other, the "Reds," who pushed for a revolutionary socialist agenda modeled after the Soviet Union. When the conflict ended in May 1918, Finnish society was left deeply scarred and divided.

Interestingly, Soviet Russia initially recognized Finland's independence and its borders in 1917. However, Stalin’s Soviet Union never fully let go of the idea that Finland was lost territory. As the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact would later reveal, the Soviets had no intention of leaving Finland alone.

In October 1939, the Soviet Union began pressing Finland with territorial demands. Unaware of the secret pact that had placed them in the Soviet sphere of influence, the Finnish government refused to give in and instead sought closer ties with Nazi Germany.

Then, on November 30, 1939, without any formal declaration of war, the Soviet Union launched the Winter War, aiming to take over all of Finland. Despite being outnumbered, the Finns mounted a fierce resistance. But, like Poland, they found themselves largely abandoned by the European powers.

Eventually, Finland was forced to negotiate peace, leading to a treaty on March 12, 1940, in which they had to cede about a tenth of their territory to the Soviet Union.

As a result, nearly half a million Finns fled from the regions conquered by the Soviets. For many Finns, this loss was seen as temporary. In fact, hoping to reclaim their lost land, Finland joined the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941—a conflict known in Finland as the Continuation War.

For decades, the Finnish government avoided publicly commemorating the Winter War, keenly aware of the sensitivities of their Soviet neighbor. The USSR downplayed the entire conflict, referring to it as a mere border incident. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that Soviet historians began to align with Finnish accounts, acknowledging Stalin’s aggressive policies. As for the Continuation War, it was celebrated in Finland for years, but in the last 30 years, it has become a politically sensitive topic. The uncomfortable truth about their alliance with Nazi Germany in 1941 was swept under the rug for a long time—and to some extent, still is today.

The Pact and Romania & Bessarabia.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact included a clear statement about Southeastern Europe:

"Concerning Southeastern Europe, the Soviet side emphasizes the interest in Bessarabia. The German side declares its complete political disinterest in these areas."

Bessarabia? If you're a fan of klezmer music or familiar with the literature and Jewish culture of Central Europe, the name might ring a bell. Positioned between the Black Sea, the Dniester River, and the Danube, Bessarabia has long been a crossroads for empires. This constant tug-of-war led to centuries of shifting borders and a vibrant mix of cultures—Romanian, Ukrainian, Russian, Jewish, and more—all woven into the region’s fabric. Today, most of Bessarabia is in the Republic of Moldova, with its northern and southern districts in Ukraine. The separatist republic of Transnistria also lies within its borders.

Historically, Bessarabia was part of the Russian Empire until it united with Romania after World War I. The victorious powers of the post-war world redrew maps with little regard for the people living within those borders. Romania didn’t just gain Bessarabia; it also annexed Bukovina from Austria-Hungary, along with parts of Hungary and Bulgaria. To this day, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán claims rights for Hungarians living in Romania.

By the mid-1920s, Romanian nationalism was on the rise, culminating in the fascist 'Iron Guard' movement. The king declared a state of emergency, banned political parties, and aligned Romania's foreign policy with Nazi Germany. Though Romania tried to remain neutral at the outbreak of World War II, in 1940 Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Soviet Union demanded the territories they had lost after World War I. The Soviet Union, in particular, kept the secret protocol of their pact with the Nazis firmly in mind.

In June 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum demanding the "return" of Bessarabia. The Red Army swiftly moved into Romanian territory. The Romanian army, completely taken by surprise, retreated in chaos. Amid this chaos, Romanian forces vented their frustration on the Jewish population, committing horrific massacres.

The memory of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Moldova and Romania has been a complex and contentious issue.

For decades, the consequences of this pact were a taboo subject in both Romania and Moldova, suppressed under Soviet influence. Even after both countries gained independence, the pact's legacy remained controversial.

Moldova, in particular, has struggled to come to terms with its past. Pro-Russian elements in society see the Soviet actions of 1940-41 as a liberation, while pro-Romanian groups view them as an act of aggression that led to decades of oppression and occupation. The latter perspective has gained momentum, especially since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Commemorating the events of 1940-41 and honoring the victims has become increasingly central to Moldova’s collective memory. Meanwhile, in Romania, the loss of Bessarabia is still felt as a deep, unhealed wound.

The Pact and… Russia.

The Danube flows like the lifeblood of Mitteleuropa, dynamic and ever pulsating. As it reaches its final stretch, it fragments into countless streams, canals and marshes, embracing the sea in a kind of quiet surrender. In many ways, the memory of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact is like those last moments of the Danube - fragmented, multifaceted and constantly shifting with time.

But what about further east, beyond the Danube, towards the Volga? How did the Soviet Union - and later Russia - deal with the memory of this pact?

For years, the Soviet Union flatly denied the existence of any secret protocols within the Nazi-Soviet pact. It was as if these dark details had been erased from history. But the dam of silence finally broke after the Baltic Way in summer 1989. In response, the Soviet government set up a commission to investigate the pact.

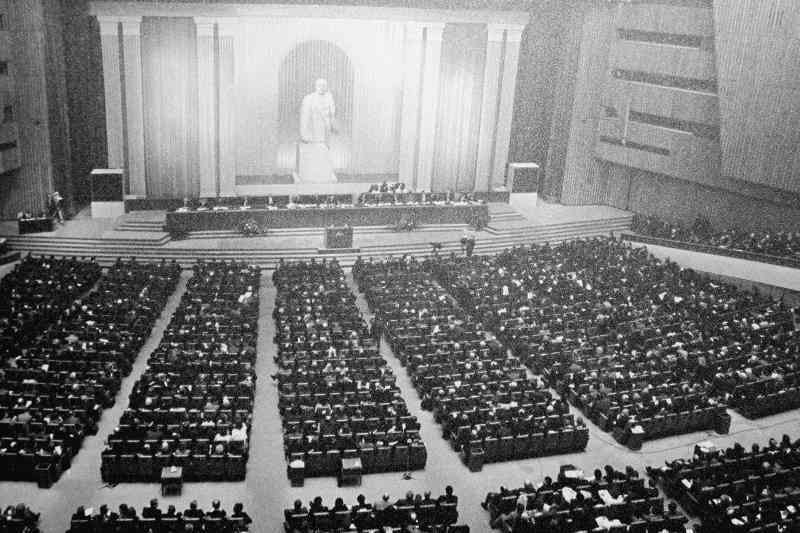

And on 24 December 1989, the Soviet Congress of People's Deputies did something unprecedented: it declared the Non-Aggression Pact and its secret protocols null and void, retroactively erasing them from the legal record as if they had never existed. That was a landmark moment in the perestroika era - a bold step towards reckoning with the injustices of the Soviet past.

But history is a story that can always be rewritten—by those who hold power.

In 2005, under Putin's leadership, Russia began to reassess the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Suddenly it was portrayed as a necessary, even wise, move to protect the Russian-speaking population.

Moscow has been drawing parallels between far-right support for the Ukrainian revolution and Nazi-era collaboration since 2014. In 2015, Russia's culture minister went so far as to describe the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as 'a great achievement of Soviet diplomacy'.

This historical reframing culminated in 2019, when Russia put the original Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocols on public display. The exhibition at the Russian State Archives in Moscow displayed not only the pact but also documents from the 1938 Munich Agreement and the occupation of Czechoslovakia—placing all these documents and agreements on the same moral plane.

The message was clear: everyone was complicit. As Russia's Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said when attending the exhibition:

"Under these circumstances, the Soviet Union was forced to ensure its national security on its own and signed a non-aggression pact with Germany."

That was a shift in narrative that speaks volumes about how memory, like the Danube, can take many forms - depending on who is telling the story.

Today, tomorrow.

Let's conclude our journey by reflecting on where we stand today. When Eastern and Central European countries joined the European Union in May 2004, they brought not only their hopes for the future but also their diverse and deeply rooted memories of the past. These memories, particularly of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, entered the European political arena and sparked debates that still resonate today.

In 2008, the European Parliament designated August 23 as a day to remember the victims of all totalitarian regimes. This decision, however, wasn't unanimous and ignited discussion.

Some feared that equating Stalinism with Nazism might diminish the unique horror of the Holocaust and risk relativizing Nazi crimes. Conversely, supporters argued that the atrocities committed under Soviet occupation deserved equal recognition to those of Nazi Germany.

Consequently, while some countries commemorate August 23, others barely acknowledge the date. One might wonder: would high school students in Lörrach, a village in the German Black Forest, know what this date signifies?

These debates aren't merely academic; they shape our collective European identity, influence diplomatic relations, and impact domestic politics, especially in nations where historical memory remains a deeply contentious issue.

So here we are in Europe, still grappling with the challenge of forging a common historical narrative. We're searching for one European story—a narrative that is honest, balanced, and acknowledges the full complexity of our past. It's not just about facts and dates; it's about understanding what shaped the Europe we live in today.

Ultimately, it's about finding a way to remember collectively, shaping a shared future in the process. From Coimbra to Charkiw. From Lisbon to Lviv.

Resources.

At the Museum Berlin Karlshorst: Rift through Europe. The Consequences of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, prolonged until 👉 26 January 2025.

The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939–1941, Roger Moorhouse, 2014

Holocaust Encyclopedia, German-Soviet Pact.

Wilson Center, Secret Supplementary Protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact, 1939

Podcast music & sounds.

Music tapestry licensed by Serge Pavkin

SFX by Pixabay

Voice and reading: me & Elevenlabs.

Share this post