«Wenn ich ein anderes Wort für Musik suche, so finde ich immer nur das Wort Venedig.» - «When I search for another word for music, I can only ever find the word Venice.»

Friedrich Nietzsche

Through the cobblestone alleyways of Venice, across the grand squares of Rome, and along the tranquil lakeside of Ascona, German-speaking souls have been drawn to the Italian-speaking world for centuries. This enduring love story, expressed through literature and painting, through music and cinema, runs deep in history.

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Europe was not divided between East and West, but between North and South: the South radiated culture throughout the continent and this culture spoke Italian. Italian was the language of great poets like Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. It was the language of intellectuals, courts, religion and the figurative arts. Faced with the majestic South, the uncultured North felt admiration and awe. With the dawn of modernity, Europe's political and cultural center shifted north and west. The South was no longer merely admired—it became a source of nostalgia, yearning, and deep affection.

This emotional connection became the defining characteristic of German-speaking classicism and romanticism, embracing both the Italian language and its territories. It could hardly have been otherwise: to love a language is to love the places where it lives. Sometimes the reverse occurs: when we fall in love with a place, it drives us to learn its language—to understand it more deeply and become part of it. This is what the Italian language becomes: a landscape of the soul.

The German word Sehnsuchtsort, born from Romantic literature, perfectly captures Italy's essence through time. More than just a physical location, it represents a place of deep yearning. Through its charm and emotional resonance, it becomes a spiritual sanctuary—a mirror of aspirations and fantasies, offering solace for personal crises and frustrations.

THE WORD:

SEHNSUCHTSORT

The German word “Sehnsuchtsort” refers to a place of deep longing and desire, often idealized in the imagination as a destination where happiness, fulfillment, or inspiration can be found. It embodies a yearning for a specific location that holds personal or cultural significance, evoking feelings of nostalgia, hope, or escapism.

According to the Digital Dictionary of the German Language (DWDS.DE), "Italien" (Italy) is the word most commonly associated with "Sehnsuchtsort".

Italienische Reise: Goethe and Romanticism.

A canvas for aspirations, a remedy for midlife crisis, and a physical and psychological journey of self-discovery: Goethe's Italian Journey from 1786 to 1788 was all of these things. First chronicled in hundreds of letters sent back to Germany, it later crystallized into a heartfelt travel diary published in 1816. This work would become the foundation for Sehnsucht—the German-speaking world's profound yearning for all things Italian.

In 1786, at age thirty-seven, Goethe was in crisis. Exhausted by his official duties at the Weimar court, financially unstable, and unfulfilled in his relationship with Charlotte von Stein, a married woman, he embarked for Italy on September 3, 1786. This was no mere break from routine or following in other travelers' footsteps—he was driven by a "demonic impulse for life and freedom." Traveling incognito as a painter, he was well-supplied with money and had reliable friends to count on locally, yet carried a heavy burden in his soul.

«Mir ist jetzt nur um die sinnlichen Eindrücke zu tun, die kein Buch, kein Bild gibt.»

«Now I am interested in sensory impressions, which no book and no image can give me.»

On September 8, Goethe crossed the Brenner Pass. From that moment, with each stop along his journey, his spirit lightened as he began to "regain interest in the world." Rather than approaching Italy as a scholar with rational tools, he experienced it as a sentient being: "Now I am interested in sensory impressions, which no book and no image can give me." Setting aside his erudition, Goethe immersed himself in the experience—practicing his Italian in Rovereto (though finding few speakers), buying local clothes in Verona, and losing himself in Venice, the most bustling city he had ever encountered.

In Rome, Goethe immersed himself in the city's pleasures. His Italian journey proved both revolutionary and therapeutic, with its modern sensibilities still inspiring readers worldwide. Italy and the Italian-speaking world gained an enduring reputation as a place of natural healing through his account. His decision to leave everything behind for two years—essentially inventing the concept of a sabbatical before it existed—was remarkable. Rather than treating it as mere travel, he embraced total immersion, ultimately reversing his perspective to view it as a return home, a Heimreise.

«Es ist mir als wenn ich hier geboren und erzogen wäre und nun von einer Grönlandfahrt, von einem Wallfischfang zurückkäme. Alles ist mir willkommen auch der Vaterländische Staub der manchmal starck auf den Strassen wird und von dem ich nun so lange nichts gesehen habe.»

«It feels as if I had been born and raised here and was now returning from a Greenland voyage, from a whale hunt. Everything is welcome to me, even the dust of the fatherland that sometimes gets thick on the streets and that I haven't seen for so long.»

On October 29, 1786, Goethe arrived in Rome, exclaiming: "Yes, I have finally arrived in the capital of the world!" While there, he took drawing lessons from his friend, the painter Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, and shared lodgings with him in what would now be called a Wohngemeinschaft (commune). This building now houses the Casa di Goethe museum. After three months, the poet embarked on a detour to Sicily, then returned to Rome before finally heading back to Germany two years after his departure. Italy, however, would forever remain his heart's true home.

Goethe's journey transformed Romantic literature: the Italian journey was no longer merely an intellectual pursuit, but became an exploration of life, freedom, beauty, sensuality, dreams, and emotions.

Clemens Brentano (1778-1842) writes in the Italienische Reisegedichte:

«O Italy, land of longing, / You homeland of my dreams, / I greet you with burning heart, / With tears in my eyes.»

«O Italien, Land der Sehnsucht, / Du Heimat meiner Träume, / Ich grüße dich mit brennendem Herzen, / Mit Tränen in den Augen.»

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) echoes this in Florentinische Nächte:

«I wandered all day through Florence, with open eyes and a dreaming heart. You know, this is my greatest joy in this city, which rightfully deserves the name la bella. If Italy, as the poets sing, can be compared to a beautiful woman, then Florence is the bouquet of flowers on her heart.»

«Ich bin den ganzen Tag in Florenz herumgeschlendert, mit offenem Auge und träumendem Herzen. Sie wissen, das ist meine größte Wonne in dieser Stadt, die mit Recht den Namen la bella verdient. Wenn Italien, wie die Dichter singen, mit einer schönen Frau vergleichbar, so ist Florenz der Blumenstrauß an ihrem Herzen.»

Italy in the Colors of Romanticism.

Not only writers but also Romantic painters drew inspiration from Goethe, journeying to Italy both physically and in their imagination. Their artistic language—expressed through brushstrokes rather than words—showed equal admiration and affection, going beyond mere landscapes with ruins or views of Rome and Venice. These works transcended simple tributes to ancient history or fascination with decaying architecture. German Romantic artists explored every corner of Italy, from the Alps to Sicily, sometimes striving for realism, other times reimagining the landscapes they encountered to heighten their emotional impact.

The view of Palermo is one of twelve Sicilian motifs that Carl Rottmann, Ludwig I of Bavaria's court painter, created as large frescoes for Munich's Hofgarten arcade. Rottmann visited Palermo twice—in 1826-27 and again in 1829—to gather material for his Italian cycle. The journey came at Ludwig I's insistence, as the king deeply desired to possess "a true Palermitan landscape." During his two-week stay in Palermo, Rottmann created numerous sketches capturing the city and bay from various perspectives.

The Nazarene painters, a German artistic group, established themselves permanently in Rome in 1809. There, they engaged in direct dialogue with Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, seeking to rediscover models of pure religious art untainted by secular influences. They drew inspiration from masters like Giotto, Raphael, and other early Renaissance painters. This quest for a synthesis between Italian and German artistic traditions culminates in Friedrich Overbeck's allegory Germania e Italia, Germany and Italy (1811-1828), now displayed in Munich's Neue Pinakothek.

Empires end, the Italian dream remains: the Central European gaze before and after the great wars.

Rilke at Duino

«The sun was shining, the sea was a brilliant silvery blue and sparkling. (...) Now it is solitude again, hopefully for a long time. I need nothing else, for me it is the primordial substance.»

«Die Sonne schien, das Meer war von einem leuchtenden silbern schimmernden Blau. (…) Nun ist wieder Einsamkeit, hoffentlich recht lange. Ich habe nichts anderes nötig, für mich ist's der Urstoff.»

R. M. Rilke letter of January 13, 1912.

For Prague-born writer Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), poetry and travel were inseparable. From childhood, he traveled extensively, with Italy becoming one of his favorite destinations (Viareggio, Florence, Venice, Rome, Naples, and Capri). He embraced the Italian language, learning it thoroughly enough to translate Michelangelo, Petrarch, and Leopardi—the latter inspiring enthusiastic passages in his Florentinisches Tagebuch ("Florentine Diary").

While Rilke visited many Italian cities, Duino—a small village on the Adriatic coast near Trieste, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—holds special significance in the public imagination. Here, as a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis, Rilke began composing his masterwork, the Duino Elegies, in 1912.

In a 1922 letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé, he reflected: "Here is where the Elegies were born, where they fell into me like seeds, to then germinate and grow slowly over the years." Italian landscapes became an integral part of his poetry, manifesting as both physical details and emotional metaphors. The musicality of Italian itself enhanced his work, contributing to the expressive intensity, rhythm, and sonority of his verses.

As Joseph Roth noted in Radetzkymarsch, "Italy is the most beautiful Province of Austria"— an observation that rings true when considering the many Austro-Hungarian authors who formed deep personal and artistic connections with Italy: Robert Musil (1880-1942), Stefan Zweig (1881-1942), Thomas Bernhard (1931-1989), Franz Kafka (1883-1924), and Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973), among others.

Musil: "In Italy, passions are stronger and more sincere".

German authors have often compared Italian and Austrian cultures—both imperial and republican—with varying degrees of ambivalence and even irony. In his monumental novel The Man Without Qualities (1930-1943), Musil portrays Italy as a perfect antithesis to Austrian mediocrity. His protagonist, Ulrich, observes that "In Italy, they say, passions are stronger and more sincere" and that "In Italy, as everyone knows, art is not a luxury but a necessity." Even for the man without qualities of finis Austriae, Italy remains an escape destination, where "everything seems easier and lighter." Yet this idealized Italy was also a place where "even the dirt was beautiful."

Kafka: Between Health Trips and Oppressive Bureaucracy.

This was equally true, though with different nuances, for Prague-born Franz Kafka, who found moments of hope and pure joy in Italy. His Italian travels marked a shift from literary sentimental journeys to the twentieth century's tourism and health retreats, exemplified by his stays at the Merano climate resort. Italian culture appears in his works indirectly and often critically—in The Trial, completed in Riva del Garda, Kafka incorporates his experiences with Italian bureaucracy. In the novel's Cathedral chapter, which alludes to his 1911 visit to Milan's cathedral, he painfully recalls feeling powerless due to his limited Italian, foreshadowing Josef K.'s experience:

«Every Italian word directed at us penetrates the vast space of our ignorance and, whether understood or misunderstood, occupies our thoughts for a long time. Our uncertain Italian cannot match a native speaker's confidence and is therefore easily dismissed, whether understood or not.»

Bachmann: "Rome is a dream from which one never wakes up".

Ingeborg Bachmann, one of Austria's most significant 20th-century writers, lived in Rome for many years until her tragic death in 1973. For her, Italy served as both refuge and muse, inspiring poems and stories while also revealing itself as a theater of contradictions. In her Roman Chronicles (1955) and Roman Poems (1952), Bachmann captures the Eternal City's paradoxical nature: bustling streets that suddenly give way to silent alleyways, sublime beauty alongside moral decay and corruption. Naples and the South evoked similarly conflicting emotions—simultaneously alluring and repelling. Bachmann didn't merely observe Italian life; she immersed herself in it completely, embracing both its virtues and flaws. Few German-language writers have achieved such deep integration into Italian culture as this Carinthian author. Bachmann articulates this dual nature of Italy in a letter to her companion Max Frisch:

«Italy is for me a double-edged sword. It is the beauty that attracts me, and the ugliness that repels me. It is the joy of living that inspires me, and the resignation that paralyzes me.» - «Italien ist für mich ein zweischneidiges Schwert. Es ist die Schönheit, die mich anzieht, und die Hässlichkeit, die mich abstößt. Es ist die Lebensfreude, die mich beflügelt, und die Resignation, die mich lähmt.»

Mann: beautiful and decadent Italy

Italy features prominently in many of Mann's works, both as a setting and as a cultural touchstone. In Tonio Kröger (1903), the protagonist is a troubled artist who journeys to Italy seeking inspiration and self-discovery. Like in Goethe's time, Italy represents an ideal of artistic freedom and creativity. The Italian landscape, with its rich cultural diversity, creates a stark contrast with Tonio's German past, compelling him to contemplate his identity and place in the world.

At Forte dei Marmi, Mann finds inspiration to write Mario and the Magician (1930). Set in this seaside resort during the fascist regime, the story develops the theme of power and manipulation through the figure of a charlatan hypnotist magician, Cipolla. With his manipulative charisma, his ability to control the crowd, and his populist rhetoric, Cipolla subjugates the audience to his power, depriving them of free will and dignity. The reference to Mussolini is evident. The ending of the story remains ambiguous: Mario kills Cipolla, but his act of rebellion proves to be a desperate and isolated gesture that doesn't change the general situation.

Finally, Death in Venice (1912) encapsulates Mann's ambivalence toward Italy. In this story, Gustav von Aschenbach, an aging writer, falls in love with a young Polish boy and succumbs to Venice's decadent allure. Through Mann's masterful prose, the lagoon city becomes a backdrop for profound themes: the tension between art and life, the decay of bourgeois society, and the nature of forbidden desire. The self-destructive atmosphere builds to its inevitable conclusion as Aschenbach, aware of a raging cholera epidemic, chooses to remain in Venice—knowingly embracing death.

A love in the spirit of Goethe that stands the test of time.

Whether viewed through loving or critical eyes, through literature, painting, or photography, Italy and Italian culture remain the Sehnsuchtsort—the "place of yearning"—for all German speakers.

In the post-war period, Italy became accessible and emerged as a tourism mecca—beautiful, happy, and carefree during the economic boom years. Yet for some, it remained a distant and forbidden dream, separated by an iron curtain that divided worlds that loved each other, from Trieste to Szczecin. When the Wall fell and Europe's many languages began speaking to each other again, an entire part of Germany—home to gems of German culture and places dear to the great romantics like Jena, Weimar, Erfurt, and Dresden—looked South toward the Alps, eager to relive Goethe's journey of freedom and dreams of new life.

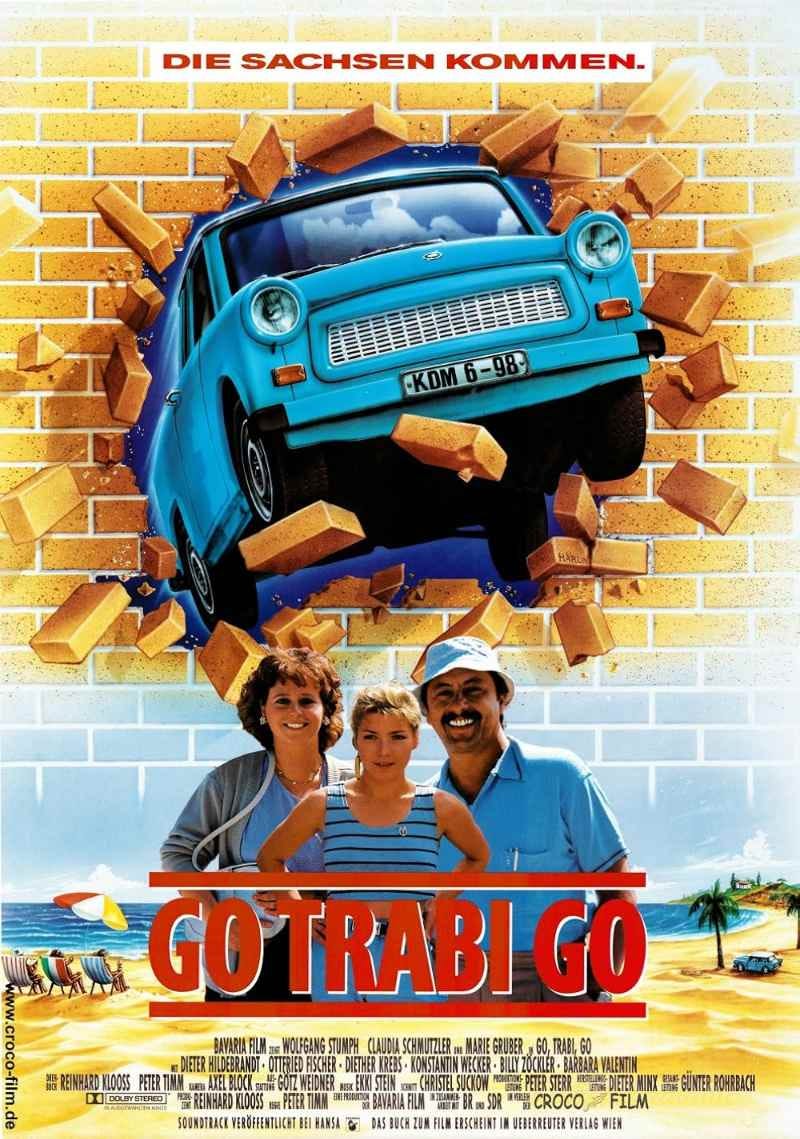

Go Trabi Go is a 1991 German comedy set shortly after reunification, during the summer of 1990—the "Magic Nights" of the Italian World Cup, won by the already unified German national team even before the country itself was unified! The film follows the Struutz family from Bitterfeld on their adventurous Italian vacation in their beloved Trabant Schorsch (every Trabant received a proper name from its owners). Udo Struutz, an East German German teacher, sets off with his wife Rita and daughter Jacqueline, using Goethe's Italienische Reise as his guidebook.

On his Trabi's trunk is Goethe's saying: See Naples and die. The journey becomes a symbol of regained freedom to travel. Despite setbacks—stolen bicycles at Lake Garda, an attempted camera theft in Rome, a car breakdown quickly fixed by its owner—the family's optimism never wavers. Their adventure continues to Naples in the Trabi, which, after losing its roof, becomes an impromptu convertible. Back in Germany, Udo learns from his wife that they're expecting a baby—a fruit of Italy and that summer when Germans were "the happiest people on earth."

Today's contemporary landscape reflects this ongoing history: Netflix series like Summertime (2023), countless books about Italy, and the endless adaptations of Donna Leon's novels - written by an American who lived in Italy for a long time before moving to Switzerland, becoming famous especially, not surprisingly, in Germany - in which Commissioner Brunetti solves Venetian mysteries. Even in music, there's Roy Bianco and the Abbrunzati Boys, a Bavarian band that captures the Italian summer spirit with songs like 'Baci, baci, baci', 'Vino Rosso', 'Amore sul mare' and, of course, 'La dolce vita', all set to the rhythms of the 1960s. This love affair, born centuries ago, shows no signs of fading.

Bookshelf

Long read worth the time, rich in lesser-known anecdotes and illuminating the before and after of Goethe's Italian Journey: Golo Maurer, HEIMREISEN: Goethe, Italy and the Germans' search for themselves (in German), 2021

Share this post