🎙️ (The podcast includes music and original tones) It's August 31, 1994, and we're in Berlin. A typical late summer day greets the city: cool mornings give way to alternating sun and light rain, followed by a milder afternoon—though still not warm enough for light clothing. At first glance, it's an ordinary day in the reunified German capital, bustling with construction sites, newcomers from the west, and even the first trickle of tourists.

But the last day of August 1994 was an extraordinary day for Berlin, for Germany, for Europe.

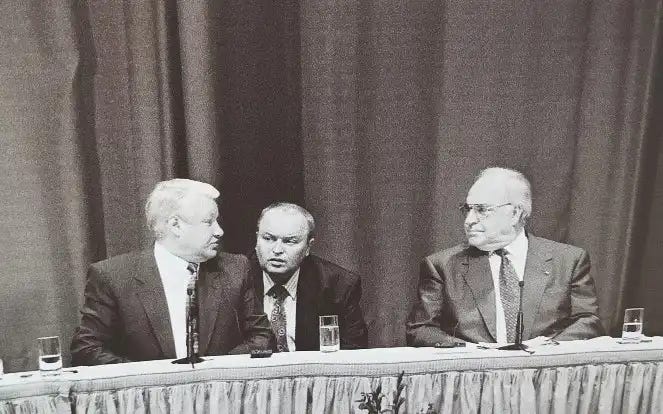

On this day, marked by ceremonies in every corner of the city, in the presence of Chancellor Helmut Kohl and Russian President Boris Yeltsin, the last brigade of Russian troops still stationed in the former GDR said farewell to the city and to Germany forever.

They marched, as soldiers do, but they also sang. A song was composed especially for the occasion, and although it did not go down in history, it remained in the memory of many of those present: "Proshchay, Germaniya", "Farewell, Germany". The refrain goes like this:

Прощай, Германия, прощай!Нас ждёт любимый отчий край.Давно угас пожар войны,Друзьями расстаёмся мы.

“Farewell, Germany, farewell! Our dear fatherland awaits us. The war fire has died down long ago, We are parting as friends.”

This is the story of a redeployment that lasted three years and eight months. A colossal movement of men and equipment, the largest ever seen in history. This is also the account of how we reached this point, of aspects that are still controversial today, and of how that complex period — marked by the birth of a new Germany and the dissolution of the Soviet Union — nurtured the hope of lasting peace and a renewed friendship with Russia.

Events took a different turn, and today we struggle to understand when and why things started to go wrong. And yet, thirty years ago, in the streets and memorials of Berlin, amidst the celebrating people, flowers thrown from the crowd, hands outstretched to greet those who were occupiers, but also friends, it really seemed that the time of wars was over forever.

The largest peacetime redeployment of troops in military history.

On the morning of September 1, 1994, a special train departs from Lichtenberg station, in the heart of East Berlin, and bound for Moscow. On board are about three thousand soldiers — the last Russians still on German soil. Despite the smiles displayed during the parades, the atmosphere is initially subdued.

Accompanying them are some local residents and the Mayor of Berlin, Eberhard Diepgen, alongside Major General Yuri Makarov. Archive footage shows the mayor conversing with the soldiers and uncorking a few bottles of Italian sparkling wine.

The videos and photographs from that day capture mostly young and slim soldiers, with light luggage: synthetic fabric duffel bags, supermarket bags, and even a cage with a canary. Some carry musical instruments with them and, while waiting, they take them out to play traditional songs and — one last time — the melody of farewell to Germany.

The withdrawal operations had begun more than three years earlier. Most people writing about this time focus on the 340,000 soldiers of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany (GSFG). But at the same time, Soviet soldiers were also leaving other countries: Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Baltic states. Between 1991 and 1994 — it's worth emphasizing — probably the largest peacetime redeployment of troops in military history took place.

In 1991, the Soviet army in Germany occupied an area equivalent to almost 3% of the GDR's territory. The number of soldiers — 337,800 — is often cited, but to these must be added about 45,000 civilian employees and over 164,000 family members. In total, more than half a million people.

As for armaments: 4,288 tanks, over 8,000 armored vehicles, about 3,700 artillery systems, almost 700 aircraft, 683 helicopters, more than 100,000 motor vehicles, 2.8 million tons of material, of which nearly 700,000 tons of ammunition.

All this was the result of forty-five years of occupation and Cold War. More than thirty years later, it's still hard to believe the rapidity of the process that led to German reunification and the dismantling of the imposing Soviet military apparatus. Today, what's even more surprising is the willingness to compromise and the mutual trust demonstrated by all the actors involved: after all, in those early nineties, everyone hoped to never again have to fill the continent with weapons and soldiers.

Treaties, phone calls... and lots of money.

The withdrawal of Soviet troops from Germany represents, after reunification itself, the pinnacle of the policy of détente between the West and the Soviet Union and its heir, the Russian Federation. This policy, in which Mikhail Gorbachev played an undisputed central role, began before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The first treaty banning land-based medium-range missiles dates back to 1987. The following year, Gorbachev announced to the United Nations the unilateral withdrawal of 50,000 soldiers and 10,000 tanks from Warsaw Pact countries.

This was followed by a complex system of treaties that led to German reunification: an intricate network that had to regulate not only internal affairs of the unified Germany but also the position of the Federal Republic in the European security architecture.. plus, the bilateral relations between Germany and the Soviet Union.

At the center of this network was the treaty known as "2+4" — two standing for the two Germanys and four standing for the allied powers: United States of America, United Kingdom, France, and Soviet Union.

The "2+4" treaty was signed on September 12, 1990. The most critical issue in the negotiation was the reunified Germany's membership in the NATO alliance: this was the most difficult condition to get Gorbachev to accept.

West Germany's trump card was economic. Aware of the Soviet Union's dire financial straits, the Federal Republic offered at least five billion German marks in credits, direct payments, and financial and logistical support for the repatriation of Soviet troops. They also promised that Germany would never possess nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons. This package of guarantees, negotiated between Chancellor Kohl and President Gorbachev, became known as the "Caucasus miracle": the Soviet Union agreed to the reunified Germany's NATO membership.

With this crucial point settled, other issues remained in finalizing the 2 plus 4 treaty. On September 10, Kohl called Gorbachev for swift negotiations, proposing additional financial commitments: another twelve billion marks as a direct payment, plus a three-billion interest-free loan.

In total, the Soviet signature on the 2 plus 4 treaty, obtained two days later, costed the Federal Republic of Germany about 20 billion marks—equivalent to 19 billion euros today, accounting for inflation over the past 30 years, or 21 billion US dollars.

The agreement on the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Germany.

A badly negotiated and mismanaged affair? The controversy continues to this day.

The Treaty on the withdrawal of Soviet troops was signed thirty days after the "2+4" treaty, and on this agreement, West and East German memories diverge. Even today, the debate on the conditions of the withdrawal and the negotiation that left many unresolved issues remains heated.

What's at the core of this controversy?

In 1990, the GDR had its first—and only—democratically elected government. Theoretically, this government could have directly managed issues related to troops stationed in East Germany, given their familiarity with military logistics on their own turf. After all, it was their home—one would assume they knew it best, right?

In practice, however, the Kohl government, during talks in the Caucasus with Gorbachev, assumed sole responsibility for this new agreement, completely shutting out the GDR government from negotiations.

This decision had both symbolic and practical ramifications, both immediate and long-lasting. From a symbolic standpoint, many in the East, particularly within the GDR government, believed that all troops—both Western and Soviet—should depart Berlin simultaneously, acknowledging their equal status. Ideally, this process would have culminated in a single, unified farewell ceremony.

The other point, more contentious—and still hotly debated—revolves around the economic agreements brokered by Chancellor Kohl and their far-reaching consequences, including environmental impacts.

Let's turn to Markus Meckel, the former Foreign Minister of the GDR. Meckel, who later served multiple terms as a member of parliament for the Federal Republic of Germany, has consistently criticized the Soviet troop withdrawal process. He argues it was poorly negotiated and—from the symbolic perspective of the farewell ceremony—inadequately managed:

Kohl decided that we—the government responsible for the territory where these troops were stationed, at least until unification—would not be involved in negotiating the withdrawal treaty. (...) This decision had consequences, and here lies the content deficit. We had the expertise, the competencies, and the preparations. (...)

Dealing with the troops had always been challenging, but there was a mixed commission that handled it. In our opinion, the process was relatively clear: a lump sum payment to the Soviet Union. Instead, what was done—absurdly—was to financially evaluate all properties, allocate that sum to the Soviet Union, and then deduct the costs of environmental damage and property issues.

This approach essentially invited the Soviet Union to cover up, conceal, and remove all existing damage during those years. I tell you, this is why much of what we still find today in forests and public squares stems from this absurd treaty.

(…) It was only changed two years later, when the issues were finally noticed, moving towards what we had originally proposed. But by then, it was too late—the damage was done.

Could the situation have been handled better?

In reality, as many historians point out, no one knew the full extent of the polluting and hazardous materials present. Neither the East German army, the Nationale Volksarmee, nor the Stasi had a clear picture. Even Markus Wolf, the head of the Stasi, later confessed:

"We knew exactly where the rockets in the West were, but we didn't know where our brothers' were."

Even the Soviet side preferred to deal directly with Kohl's Federal Republic. Their reasoning was simple: "We're getting money from Bonn, so why concern ourselves with the GDR government?"

Regarding environmental and ecological damage, the Soviet army indeed "forgot" to report hazardous materials' locations to avoid problems and financial losses. Moreover, the forests of Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania were already riddled with unexploded ordnance from World War II. These areas, used for military exercises, remained uncleared and unmarked for future use. The consequences persist today: during exceptionally hot summers, forest fires create dangerous "fireworks" displays where numerous munitions remain hidden.

The troop withdrawal agreement was swiftly finalized on October 12, 1990 — partly due to fears of future renegotiation. Two and a half months later, the Soviet Union dissolved, raising concerns about potential treaty revisions. However, these fears proved unfounded: the new Russian Federation pledged to honor the agreed-upon withdrawal of former Soviet troops.

In December 1990, Colonel General Matvei Burlakov (1935-2011) assumed command of the Western Group of Russian Forces to oversee the withdrawal—a task he completed several months ahead of schedule.

Move out, but to go where?

For days, a loud noise could be heard all over East Germany, in both big and small towns. Near the military bases that were being taken apart, you could hear trucks full of stuff leaving and things being moved onto trains. It sounded like a huge moving day that went on for years.

In January 1991, they started emptying out everything: army buildings, checkpoints, houses, and storage places. Sometimes, they took almost everything. German army officers, who were supposed to get the keys from the Soviet soldiers, were shocked when they went into some buildings. They found them completely empty inside.

But when we arrived for the actual handover four or five days later, the barracks commander took us around again and I shook my head and asked: "What have you done here...?" The floors were missing, there were no more sinks or taps, windows and doors. Everything had been ripped out and taken away.

What couldn't or wouldn't be removed was concealed. Toxic and hazardous substances, which the withdrawal treaty deemed grounds for reducing German payments, were hidden underground or within walls. Consequently, each building handover prompted a thorough inspection to prevent nasty surprises.

Outside, German intelligence service experts from the Bundesnachrichtendienst sifted through piles of waste discarded daily by the Soviet army during withdrawal operations. These Western agents, unfamiliar with Russian, collected all written materials: from regimental canteen menus and invoices to old "Pravda" copies and, if fortunate, even confidential documents.

After filling their often malodorous bags, they loaded them onto small buses bound for a West Berlin station. There, the American military intelligence service "Defense Intelligence Agency" (DIA), staffed with Russian-speaking agents, would analyze the contents.

More direct methods of material collection also existed. Soldiers and officers facing repatriation were willing to sell or trade their possessions for valuable goods. Occasionally, a small used car dealership would pop up near the barracks—a front for exchanging old vehicles for documents. At times, the scene resembled a village market: the same Berlin-bound buses traversed the provinces, laden with household appliances to swap with barrack soldiers for documents. In some instances, these papers were even bought "by weight".

How did the East Germans living around these barracks react?

Despite the GDR's efforts to promote Soviet-German friendship, the relationship between locals and soldiers was unique: generally amicable and respectful, but with limited personal interactions beyond those organized by the party, schools, or local groups.

During village festivals, people would mingle, and many recall that these soldiers, often from distant places, were always ready to help: clearing snow from roads, felling trees, or repairing equipment.

Over time, coexistence proved successful. Residents who witnessed the departure of soldiers and their families—some officers having lived in Germany for years—felt compassion. Everyone understood these soldiers faced an uncertain future, often without guaranteed housing.

To address this, Federal Germany committed to financing 35,000 apartments in 40 locations across Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine by 1994.

This ambitious program, budgeted at 8.3 billion German marks, involved international tenders as per European regulations. Companies from Turkey, Slovakia, Finland, and South Korea participated. This diversity benefited both German taxpayers and Red Army soldiers, as lower costs allowed for over 8,000 additional apartments to be built.

However, despite these efforts, the housing crisis for this vast number of soldiers remained unresolved. The demand far outstripped supply. Old videos, some available on YouTube, show entire divisions—16,000 to 20,000 soldiers—being relocated to forests, living in field tents for months before finding proper accommodation.

Many soldiers wept as they disembarked from buses, realizing that after Weimar, Rostock, Dresden, or Berlin, their new home would be a forest.

January to June 1994: farewell parades and final negotiations.

As the redeployment progresses, we enter its final months. By early 1994, withdrawal operations are well underway. At a press conference held at the Russian embassy on January 25, 1994, Colonel General Matwei Burlakov, tasked with this monumental operation, expresses unwavering confidence in the plan's timeline.

Yet, one contentious issue remains: the Berlin Senate's proposal to hold separate farewell ceremonies for Soviet soldiers and Western Allies. This notion strikes a nerve in the Russian embassy, seen as insensitive and potentially damaging to future German-Russian relations.

The farewell ceremony debate threatens to escalate, stirring internal tensions in East Germany. The still-in-office GDR government, echoing Russian sentiments, advocates for a unified ceremony. Conversely, the Bonn Government leans towards hosting the Russian ceremony in Weimar, away from Berlin.

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, Chancellor Kohl intervenes personally. He brokers a compromise: the Russian army will indeed have its parade in Berlin, but separate from the Western allies.

From that moment, with the dismantling of the last and most significant Soviet military structures in the GDR, a three-month period of parades—both large and small—began.

The atmosphere was predominantly festive: band music drowned out the noise of moving vehicles, and the troops' marching no longer evoked fear. These ceremonies also served as "open days": for many Germans—neighbors who had been strictly excluded from these facilities—the Russian-organized military parades offered the first chance to enter the barracks and visit the airports.

Among the best-documented parades, the one held by the 6th Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade in Wuhlheide, a district of Berlin-Köpenick, on June 25, 1994, stands out.

Unlike the concluding ceremonies on August 31, which were restricted to a limited audience for security reasons, this was a true public spectacle that unfolded on one of East Berlin's characteristic wide boulevards. To protect the roads, tracked vehicles were prohibited—the Russian armed forces even forgoing their iconic T-72 tank. Yet, even the lighter infantry fighting vehicles left deep imprints in the asphalt, softened by the summer heat.

August 31, 1994: a marathon of ceremonies.

The 31st of August 1994 unfolded as a marathon of ceremonies, with each party adding its own touch.

The Germans wanted to show friendship and respect for Russia, perhaps aware that the absence of a joint ceremony with Western allied troops might cast a shadow over an otherwise smooth process. For the Russians, showing their soldiers at their best - with grand parades, flawless marches and plenty of music - was a matter of pride and dignity. While departure was inevitable, they were determined to leave with their heads held high, emphasising their role as liberators rather than occupiers.

The day began at dawn with an official ceremony in the central Gendarmenmarkt. Chancellor Kohl and Boris Yeltsin were present, side by side, for every moment of the day's marathon ceremony. In the square, framed by some of Berlin's most iconic buildings, Colonel General Matvei Burlakov stood before the two statesmen and formally concluded the Russian withdrawal (full audio here):

Mr. President of the Russian Federation, Supreme Commander of the Russian Armed Forces, Mr. Federal Chancellor of Germany, I report that the intergovernmental treaty on the temporary stay and planned withdrawal of Soviet troops from Germany has been executed.

In three years and eight months, we have withdrawn from Germany to Russia and other countries of the Community six armies, consisting of 22 divisions, 49 brigades, and 42 independent regiments. In total, 546,200 people, 123,629 units of equipment and armaments, and 2,754,530 tons of material supplies, including 677,000 tons of ammunition, have been transferred.

The success of the withdrawal of the Western Group of Forces was made possible thanks to the high professionalism and training of the personnel, the discipline of the troops, the precise guidance of the Russian leadership and the Ministry of Defense, and the effective coordination of commanders and staffs.

Also fundamental was the close collaboration with German federal and local authorities, with the Bundeswehr, governmental and social organizations, as well as the great support of the German population. The strategic intergovernmental operation for the withdrawal of the Western Group of Forces is now concluded.

The dignitaries then proceed to the Konzerthaus. While the event is primarily musical, it naturally includes the day's initial speeches. However, it's at the Treptower Park memorial, during the ceremony directly overseen by the Russian army, that the most poignant words are spoken—particularly in Boris Yeltsin's address.

Treptower Park houses the most renowned Soviet memorial in all of East Germany and Europe. Here, Russian troops have orchestrated a military parade featuring representatives from every branch of the armed forces—all men, of course. The vehicles have already been relocated, as this isn't an appropriate venue for displaying weapons and tanks. Approximately 8,000 Red Army soldiers rest here, guarded by the iconic statue of a soldier holding a child while trampling a broken swastika.

Yeltsin's speech begins by acknowledging the scars of World War II—still referred to by Russians as the "Great Patriotic War"—before shifting to themes of peace. He expresses gratitude to the East Germans, especially those who resisted National Socialism. Yeltsin highlights how, during those dark years, these citizens chose to live by their conscience rather than succumb to falsehoods:

“Honor and glory to the participants of the resistance, to the partisans, to the German anti-fascists. With their selfless struggle, they helped liberate the planet from the brown darkness.

Our deep gratitude goes to the citizens of occupied countries and territories. In particular, to those Germans who in their hearts rejected the infamous "new order," who did not sell their souls to the demon of National Socialism and who, in those dark years, chose to live according to their conscience rather than in lies.

On behalf of all Russians, on behalf of Russia and myself as president, I say today: rest in peace. Your names will live on in the grateful memory of posterity, and the tragedy of that war will not be repeated.

Sincere gratitude to the German citizens who guard the graves of the fallen, and today we see this.

Today is the last day of the past, but I am convinced that with our joint efforts it can, it must become the first day of the future.

A future in which there will be no place for violence, in which the universal hopes for peace and mutual understanding among the peoples of the earth will be realized.

Today is the day of final reconciliation.”

On this occasion, the song "Прощай, Германия" (Farewell, Germany), which we heard at the beginning is performed.

The day stretches on. Following lunch at the Federal President's residence, Kohl and Yeltsin honor the Soviet memorial in Tiergarten, across from the Brandenburg Gate. This monument, situated in the west, had been guarded by Red Army troops until 1990, when they handed it over to their German federal army counterparts. The two statesmen then lay wreaths at the Neue Wache, the monument to the unknown soldier on Unter den Linden avenue, a stone's throw from the Russian embassy.

The truly memorable images from August 31, 1994, however, came from the late afternoon. Boris Yeltsin, welcomed by Berlin's mayor, signed the guest book with a flourish. Outside the palace, he first conducted the Berlin police orchestra and then joined a choir in belting out the famous Russian folk song "Kalinka". Yeltsin's fondness for alcohol was no secret: the lunch with the German President, generously accompanied by wines and champagnes, had transformed the Russian president's initially solemn demeanor into a decidedly more spirited one. But the day was unfolding splendidly. Not only had everything proceeded with order and dignity, but there was a palpable atmosphere of friendship—even brotherhood—in the air.

August 31 had gone smoothly: the final withdrawal operations, ceremonies, and cordial response from the population.

The following day, 1 September, as the last soldiers left German soil on the special train from Lichtenberg, the atmosphere was more relaxed. Berlin's mayor is smiling, as are Major General Yuri Makarov and those bidding farewell to the military. The soldiers, however, appear less cheerful. As the train pulls away, German army soldiers—the Bundeswehr—can be seen on the platform. They don't offer a military salute, but smile and wait. From this moment on, they will assume the role once held by the Red Army.

When did things go off track?

Reflecting on the events of that period, a crucial question emerges: how did we arrive at the current crisis, the most severe since the Cold War?

The 1990 Paris Charter, signed at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), aimed to end the "era of confrontation and division in Europe" by promoting human rights, mutual respect, and peaceful conflict resolution.

The following four years saw intense disarmament efforts.

Treaties like the 1990 CFE on conventional forces and the 1991 START I on strategic arms reduction significantly decreased armaments. The 1992 Lisbon Protocol managed the transfer of Soviet nuclear weapons to Russia, with Ukraine relinquishing its arsenal in exchange for territorial integrity guarantees. Additional agreements addressed chemical weapons and short-range nuclear systems, while the former Soviet army withdrew from Warsaw Pact countries.

Russia entered a period of uncertainty, marked by partial democratization, instability, and the Chechen conflict. This led former satellite states to perceive Russia as a threat.

Consequently, Central and Eastern European states sought security, pushing for NATO membership from 1993. Europe and the United States initially exercised caution, concerned that NATO expansion might provoke Russia, risking tensions while pursuing a new partnership. Ongoing disarmament and the withdrawal of Soviet troops also raised concerns. At first, efforts were made to redirect aspirations towards EU membership, seen as less contentious.

The Budapest summit of December 1994, which officially transformed the CSCE into the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe), marked a negative turning point. Russian President Yeltsin issued a stark warning: NATO's eastward expansion would plunge Europe into a "cold peace".

A final reconciliation attempt occurred in 2002 with the establishment of the NATO-Russia Council under new Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Conceived as a forum for information and cooperation, it nonetheless failed to prevent NATO's major expansion in 2004. The accession of the three Baltic states, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia, and Slovakia further alienated Russia from the West.

In 2007, Russia suspended the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, toppling a key pillar of the disarmament architecture. This marked the beginning of a rapid erosion of the once-solid disarmament system.

At the 2007 Munich Security Conference, President Putin leveled serious accusations at the West. He cited the wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq as examples of manipulating international law, undermining disarmament agreements, and violating promises about NATO's eastward expansion. The only verifiable promise, however, had been made to Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990—not to move NATO sites from West Germany into East Germany. Putin's Munich speech—available in full on YouTube—is widely considered a turning point.

The rest, as they say, is recent history.

Thirty years ago, as Berliners bid farewell to departing Russian soldiers, hope for peace was palpable. There was a sense that a historic era had ended. The rumble of tanks on European roads, the nuclear threat, and the notion of states as spheres of influence or objects of territorial partition seemed relics of the past. Perhaps this optimism was tinged with naivety, or perhaps it was justified.

Regardless, events have taken an unexpected turn. Things haven't unfolded as hoped. Yet, the opportunity to set history back on the right course remains within our grasp.

CREDITS

YT Channel: RedSamurai84

YT Channel: Militär-Wissensbasis

YT Channel: RBB Media

YT Channel: AP Archive

Markus Meckel, Zu wandeln die Zeiten (Changing times - Memories), 2020

The hope of eternal peace with Russia. The Russian troop withdrawal 1990-1994. Public event, 23 July 2024 at the Museum Berlin Karlshorst (YT video here, DEU)

Share this post