When a Country's Brightest Minds Flee

Expelled or unwanted, when a nation's brightest minds leave, they set history in motion—and history favors those who welcome these exiles, not those who drive them away.

Whether driven by Mussolini or by Goebbels, by Pinochet or by China's Politburo, it's always the same tactic: The state leans on university administrators, who lean on professors and students. Italian Fascists leaned on university rectors to scrutinize the politics of those whom they oversaw: The rector of Milan's Catholic University actively informed on politically anti-Fascist students to the secret police. […] Germany emulated the tactic: From the early 1930s, professional purges led so many Jewish and "communist" academics and scientists to emigrate that this led to a major brain drain. By 1933, about 2,000 of the nation's premier artists and writers had fled as well. The Nazi periodical The Nettle (Die Brennessel) depicted this emigration as "a triumph for the German nation."

Naomi Wolf, “The end of America : letter of warning to a young patriot”, 2007

Jason Stanley, philosopher, Timothy Snyder and Marci Shore, historians: three of Yale's most distinguished voices on democracy and authoritarianism announced two weeks ago their decision to leave the faculty and the United States for Canada. The move sent shockwaves through academia and made headlines across the world.1

In those same days, a survey by the science journal Nature revealed a looming exodus in the American scientific community. Among 1,600 respondents, more than 1,200 scientists—three-quarters of those surveyed—reported they are actively considering leaving the United States due to Trump-related disruptions.

Shortly afterwards, the German news outlet Deutsche Welle ran this headline: “Dear US researchers: Welcome to Germany!", "Liebe US-Forschende: Willkommen in Deutschland!". Germany's most prestigious research institutes confirmed that applications from the US had doubled or even tripled in recent weeks. The Max Planck Society set out with an ambitious vision: to actively recruit leading minds from the US. Meanwhile, the Baden-Württemberg government plans to set up a new state agency to streamline immigration procedures for skilled workers.2

It's hard to predict whether these movements will become a mass exodus of intellectual talent from the USA to Europe. While Germany offers a prestigious destination, it faces quiet but significant challenges in retaining such talent. Making predictions about anything these days seems futile. Yet for those who believe in History's karmic cycles and the healing power of Tikkun, there's something profound in seeing "pathetic" Europe potentially become a safe haven where brilliant minds can freely contemplate the past and shape together the future.

This mirror image of the 1930s exodus of German and Austrian academics, scientists, and artists holds lessons for "great again" America: much of what made America great came from these very people, who fled or were expelled two generations ago.

While most know about the scientists who found refuge in America, there is a lesser-known but even more fascinating side story about other nations seeing the opportunity where others saw crisis.

One such story is that of Türkiye (Turkey) under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a country that would radically transform itself by welcoming these women and men. This lesser-known chapter of history is what I'll explore in this post.

The canonical story: American culture made great by European refugees.

The larger story is well known: between 1933 and 1941, some 500,000 people fled Germany and annexed Austria due to the rise of National Socialism. In October 1941, the Nazi regime imposed a general ban on Jewish emigration, trapping an estimated 200,000 people.

Thousands of intellectuals, scientists and artists, mostly of Jewish origin, were among the first wave of this exodus, which began when the Hitler government passed the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums) on 7 April 1933. This law excluded almost all Jews and political opponents from civil service positions.

Some 3,000 academics immediately lost their university positions. Many more fled in the following years: by 1945, German universities had lost about a fifth of their teaching staff. Many of those minds would find new homes—and new influence—across the Atlantic.

The exodus to the United States has often been called the greatest cultural transfer since 1453, when scholars fleeing the fall of Constantinople helped ignite the Italian Renaissance. In the 1930s and ’40s, German science, philosophy, art and literature seeded a revolution in American academia and culture, with around two-thirds of the 3,000 scholars expelled from Germany finding refuge in the United States.

NYU art history professor Walter William Spencer Cook, who played a prominent role in introducing eminent German art historians to the United States, declared: "Hitler is my best friend. He shakes the tree and I pick the apples.”

The other story: from Berlin to the Bosphorus.

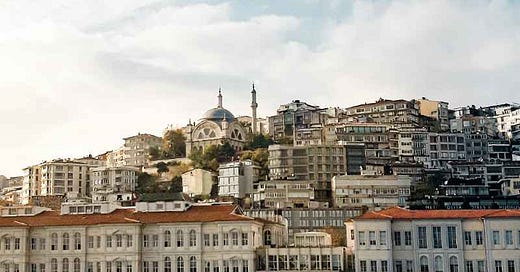

History does not simply repeat itself but moves in cycles—new patterns can emerge and conclude in the same places where earlier cycles unfolded, sometimes taking the opposite direction. Istanbul and the Bosphorus stand as one of history's great crossroads, a place from which scholars, scientists, and artists once fled, only to become, five centuries later, an unlikely yet providential haven.

"For everything in this world, for material things, for spiritual things, for success, science is the only true guide. To seek a guide other than science is negligence, ignorance and deception." • " As in political and social life, science and the natural sciences will also be our guide in the spiritual education of the nation."

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey was reborn as a republic in 1923 under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. A brilliant general — the only one in the Ottoman army who had never tasted defeat — Atatürk was also something much rarer in military leaders: a devoted intellectual. He was an omnivorous reader, a firm believer in science, reason, and education as engines of national strength. He knew that the Ottoman Empire had fallen behind Europe not only militarily, but culturally, technologically, and scientifically.

From the start, Atatürk was clear: the true victories of the future would come not through bayonets, but through books and laboratories. With this vision, he launched an ambitious reform project to build a modern, secular nation.

Women gained the right to vote in 1934, making Turkey one of the early adopters of women's suffrage in the Middle East—ahead of many European countries. The government introduced free, mandatory primary education, adopted the Swiss Civil Code and Italian Criminal Code, removed Islam as the state religion in 1928, and replaced the Arabic script with the Latin alphabet. Nothing was off the table.

A key piece of this puzzle was Education.

Atatürk knew that reforming the universities was essential. But Turkey didn’t just need new textbooks — it needed new minds. Scientific minds. Artistic minds. Modern minds. And so, starting already in the mid-1920s, the Turkish government began recruiting professors and assistants from abroad — especially from German-speaking countries, whose academic system Atatürk admired — to help modernize its institutions.

Then came 1933.

The rise of National Socialism in Germany changed everything. When the so-called Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service passed, some of the Europe´s best brains found themselves jobless overnight — and in danger. And here’s where the stories converge. That same year, Istanbul’s old university, the Dârülfünun, was shut down. In its place rose a new institution: Istanbul Üniversitesi, founded to be the beating heart of the Turkish Republic’s new academic life. The timing was fit. The Turkish government, eager for expertise and reform, saw an opportunity — and opened its doors.3

Through the efforts of people like Philipp Schwartz, a Jewish pathologist who had himself fled Nazi Germany, persecuted scholars were connected with positions in Turkey. Schwartz founded the Emergency Association of German Science Abroad in Zurich and helped over 2,600 scholars find placements — many of them in Turkey.

In the winter semester of 1933/34 alone, Istanbul University hired around 30 Jewish professors. Over time, Turkey became home to around 1,000 German-speaking exiles: professors, assistants, technicians, artists, and their families. They came from every field — medicine, law, architecture, agriculture, the arts. Some names you might recognize: the architect Bruno Taut, urban planner Gustav Oelsner, physician Albert Eckstein, botanist Leo Brauner, and future Berlin mayor Ernst Reuter.

This was not a simple act of charity.

The Turkish state had a clear goal. These émigrés were not just guests — they were instruments of reform. Their mission? To train a new generation of Turkish academics who would eventually take over and carry their disciplines forward. Contracts were temporary, usually five years. They were required to learn Turkish quickly enough to teach and conduct research in the national language. This was integration by design — and it worked.

By 1940, Turkey had opened its Technical University, and many of the emigrants were still working in the country. In some faculties, like Natural Sciences, nearly all the chairs were held by foreign scholars. Their impact was enormous. They didn’t just fill posts — they planted seeds. Many of their Turkish students would go on to become professors themselves, founding new departments and carrying Turkish academia into the modern era.

These scholars lived in uncertainty. The Nazi regime kept tabs on them. In 1939, the German Reich sent representatives to Turkish universities to report on how many Jews and “non-National Socialists” were teaching there. The NSDAP had an active foreign organization in Turkey, and exiled scholars were understandably fearful of being spied on, denounced, or pressured to return. But the Turkish government's response to Nazi interference was firm: only Turkey would decide who would teach what and how in its universities.

Still, life wasn’t easy. Those who had been denaturalized by the Nazis were stamped as “homeless” (heimatlos) in their passports — a word that entered Turkish as heimloz or haymatsloz, eventually appearing in dictionaries with meanings like “stateless”, “wanderer” and “unstable.” Stateless individuals weren’t technically allowed to reside in Turkey, which forced many exiles to make difficult choices: convert to Islam to gain citizenship, move on again, or try to extend their contracts and stay in legal limbo.

Despite the challenges, many chose to remain — and contribute. Most left after the end of the Second World War or later in the sixties, but all kept sweet memories, gratitude and an emotional linkage to the Country that was not only refuge, but a place where they could give their best.

Let's look at six of the thousand stories of academic refugees in Turkey, starting with the one whose cooperation with Atatürk's Turkey is still seen as a pivotal moment in the cultural history of the country: Philipp Schwartz.

SIX STORIES FROM A THOUSAND: Philipp Schwartz • Ernst Reuter • Ernst Eduard Hirsch • Rudolf Belling • Bruno Taut • Alfred Heilbronn

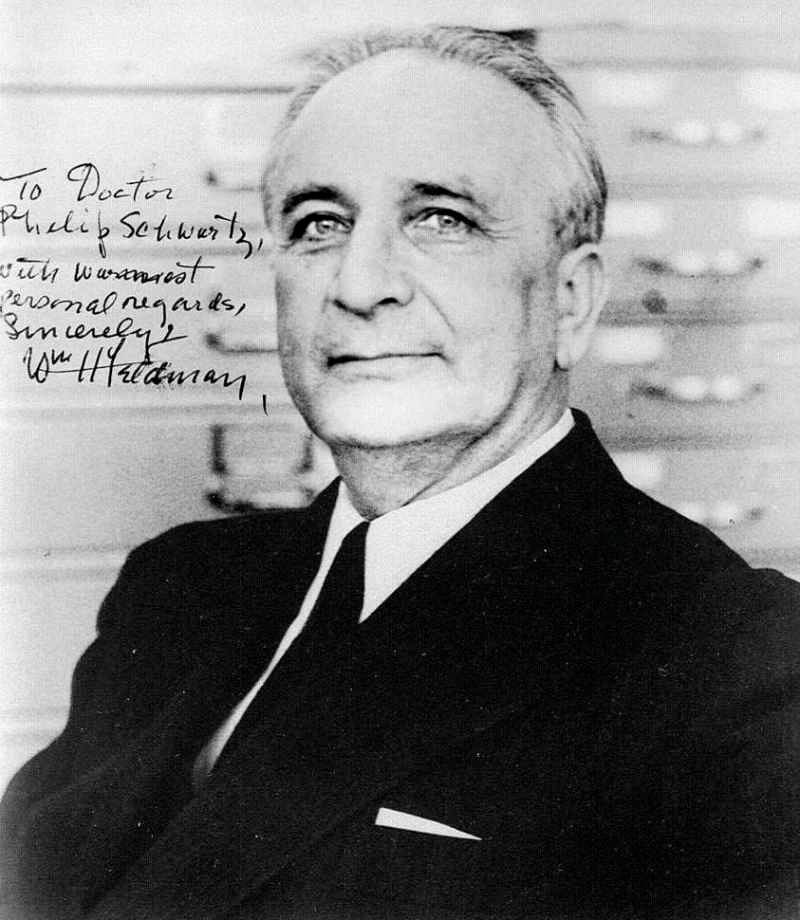

Philipp Schwartz

From Frankfurt to Istanbul: The quiet hero of academic rescue.

In the summer of 1933, a modest, soft-spoken neuropathologist named Philipp Schwartz arrived in Ankara with a purpose—and with little idea just how far his influence would reach. Only months earlier, Schwartz had fled Frankfurt. In Zurich, he founded the Emergency Association of German Scientists Abroad, a lifeline for displaced academics. His goal was simple: find jobs for his colleagues before it was too late.

At the same time in Istanbul, the Turkish government had asked Swiss education expert Albert Malche to review the country's university system. His suggestions for modernization initially struggled to take hold, largely due to difficulties finding qualified professors. A local Zürich rabbi told Philipp Schwartz about Malche's work. Schwartz contacted Malche, and soon Schwartz was in Turkey to meet with the Turkish Minister of Education. His hope for this first meeting was to secure three academic positions for his fellow exiles. He never expected the meeting would last seven hours—when he walked out, he had secured thirty professor positions!

By the end of 1933, 42 German academics had taken positions in Istanbul, most with five-year contracts and competitive salaries. Even Albert Einstein considered an offer from Turkey before ultimately settling in Princeton. Schwartz himself became chair of pathology at Istanbul University in October 1933—a post he would hold for nearly 20 years.

Some exiles even joked that Istanbul had become "the best German university". Still, Turkey wasn't paradise. Arthur von Hippel, a materials scientist, described how Turkish customs officials confiscated his 18 cases of laboratory equipment. He scoured Istanbul's bazaars for supplies before finally leaving for Copenhagen in 1934. Others later emigrated again - mostly to the US or the UK.

During his 20-year collaboration with the Turkish Ministry of Education, Philipp Schwartz transformed the medical faculty of Istanbul University by recruiting prominent professors from Germany and Austria for almost all faculties.

In 1951, Schwartz was given back the title of full professor at Goethe University in Frankfurt as part of the reparations program, but was not offered an actual position.

In 1957, he attempted to return to Goethe University, but the Faculty of Medicine rejected his application for a professorship, claiming he was too old at 63—while several professors of the same age with Nazi pasts retained their positions. Philipp Schwartz died in Florida on December 1, 1977. After his wife's death in Zurich, his daughter, psychiatrist Susan Ferenz-Schwartz, had his urn transferred to Zurich.

It wasn't until 2014 that the University of Frankfurt finally honoured Professor Schwartz as the "great saviour of the idea of science" with a stele on its medical campus.

On three sides of the monument are the names of scientists who were saved by Schwartz's initiative. Today, the German Humboldt Foundation runs a programme to support scientists who have fled their countries by helping them to secure research and academic positions in Germany.

Ernst Reuter

From Berlin to Ankara: a city planner in exile.

Less than a decade before his exile in Turkey, Ernst Reuter, a Social Democrat serving as Berlin's transport councilor, transformed the city's transportation system. He created an integrated network combining U-Bahn, S-Bahn, trams, buses, and ferries under a unified fare structure, connecting outer districts to the city center. This pioneering system remains the foundation of Berlin's public transport today.

After being branded a communist by the Nazis and forced from public life, Reuter fled Germany—first to Holland, then England, before finally reaching Turkey in 1935. Initially, he worked in the Turkish Ministry of Economy, quickly mastering the national language, before moving to the Ministry of Transport. There, he focused on reorganizing railway tariffs and redesigning the coordination between rail and coastal shipping services.

By 1938–39, Reuter's path took a decisive turn. He became a professor of urban development and planning at Ankara's Siyasal Bilgiler Yüksek Okulu—the School of Political Sciences—which was later integrated into Ankara University.

In a country undergoing rapid transformation, Reuter's pragmatic rather than revolutionary ideas about how cities should be built and organized found fertile ground.

Reuter's teaching style diverged sharply from the country's academic traditions. He encouraged students to interrupt him whenever his Turkish wasn't clear or when urbanistic terms weren't properly translated. More radically, he fostered open discussion, welcomed dissent, and urged students to think independently and question established authorities. This approach earned him deep admiration from his students and colleagues.

Though Turkey provided a safe haven, exile came with restrictions. Like other émigrés, Reuter faced a ban on political activities—a constraint he endured with stoic resolve while maintaining hope for Germany's future rebirth, both structural and spiritual. He saw himself as "bound by indestructible threads" to his homeland, and although Turkey offered both beauty and welcome, it remained for him an "involuntary exile." Yet in 1943, despite these political restrictions, Reuter helped establish the Deutscher Freiheitsbund—the German Freedom Union. Together with other exiled intellectuals, he developed plans for a democratic Germany.

Reuter returned to Germany at the end of 1946 and in December became Berlin's City Councillor for Transport and Utilities. Less than two years later, he emerged as the leading figure during the Berlin Blockade: he rallied the city's population and persuaded the Allied Armies Generals to fully support the resistance. The famous Berlin Airlift that followed proved a lasting success, leading to Reuter's appointment as West Berlin Mayor in December 1948. He held this office until his death in 1953.

Ernst Reuter never forgot his Turkish exile. In 1947, he wrote a newspaper essay titled "Türkei im Brennpunkt"—Turkey in Focus—offering a nuanced and affectionate account of the country that had taken him in. He described Istanbul as "the most beautiful place on earth in Europe." He urged his readers—and his political allies like Willy Brandt—to understand each country in its own context, to practice empathy across borders. Through his story, the German public came to understand something many had overlooked: that a chapter of German democratic renewal had, improbably, begun in exile—in the classrooms and ministries of Ankara.

Ernst Eduard Hirsch

A German jurist and the making of modern Turkey’s Commercial Law.

When Ernst Eduard Hirsch arrived in Istanbul in the autumn of 1933, he carried little more than his legal expertise and the scars of forced exile. A Jewish professor, he was one of many scholars whose careers had been cut short in Germany.

With the help of Philipp Schwartz's Emergency Association of German Scholars Abroad, Hirsch joined Istanbul University as a professor of commercial law. At first the challenges were immense. He gave his first lectures in German, awkwardly interpreted by translators who struggled with legal terminology. But Hirsch persevered. He learnt Turkish, swapping law lessons for language lessons with one of his most promising students, Halil Bey, who went on to become not only his successor but also a lifelong friend.

Over time, he became more than a guest professor - he became a builder of Turkey's legal system. Hirsch played a pivotal role in Turkey's legal revolution, guiding the transition from Islamic Sharia to European-based law.

He transformed the university library system, published legal texts in Turkish and wrote a comprehensive commentary on the Turkish Commercial Code - a work he proudly called "my Commercial Code". Many of his principles still underpin Turkish law today.

Hirsch's connection with Turkey ran deep. After being stripped of his German citizenship in 1943, he became a Turkish citizen. He gave his son, born in Istanbul in 1945, two Turkish first names - Enver Tandoğan - in honour of his adopted country. Although he never converted to Islam, he was naturalised without any problems. His embrace of Turkish identity was rooted not in opportunism but in sincere gratitude and respect. But exile also brought pain: Hirsch never recovered from the loss of his sister and her family in Auschwitz. But he persevered because he believed in rebuilding - not just nations, but systems, institutions and ideals.

In 1953, after nearly two decades in Istanbul, Hirsch returned to Germany to become rector of the Free University of Berlin.

For his son Enver, this meant attending a German primary school for the first time. Hirsch's experiences in Turkey profoundly influenced his academic development, shifting his focus from legal dogmatics to the sociology of law. This transformation led directly to his founding of the Institute for Sociology of Law at the FU Berlin.

Even after returning to Germany, Hirsch maintained his fluency in Turkish. His autobiography—"From the Emperor's Times through the Weimar Republic to Atatürk's Country" ("Aus des Kaisers Zeiten durch die Weimarer Republik in das Land Atatürks")—provided a unique glimpse into the complex experience of exile and transformation.

The legacy of the jurist Ernst Eduard Hirsch on Turkish commercial law is still significant today. He is recognised as a pioneer in revolutionising Turkey's legal system and his legal texts, including the country's Commercial Code, are still in force today.

Rudolf Belling

Sculpting a new life on the Bosphorus.

The Berlin sculptor Rudolf Belling's Turkish chapter began in 1937 when he accepted an offer to establish the sculpture department at the Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts (Güzel Sanatlar Akademisi). In Germany, Belling had been a prominent member of the avant-garde "Novembergruppe" and had championed abstraction in sculpture.

Under the Nazi regime, Rudolf Belling faced a paradoxical situation: while his bronze sculpture of boxer Max Schmeling was displayed at the Great German Art Exhibition in 1937—an event personally curated by Hitler—other works of his were denounced as "degenerate" and included in the notorious Entartete Kunst exhibition.

Art cannot exist without freedom, which is why the decision to begin a new chapter in Istanbul was significant. Under Atatürk's leadership, the city held strong artistic ambitions. His modernizing vision made art and architectural education a top priority.

The Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts had recently merged with the former women's art academy and stood at the heart of this transformation. When Belling accepted the offer to found the sculpture department at the Academy, expectations ran high. In Istanbul, he discovered a fresh sense of purpose. Though the sculpture department had lain dormant since 1924, Belling immediately set to work, crafting a rigorous curriculum rooted in classical principles. His teaching manifesto advocated a return to nature and life, rejecting what he called "bloodless, encrusted art."

With full support from the Ministry of Education, he received significant autonomy to implement his vision.

Belling immediately began to restructure the sculpture programme, emphasising a return to the principles of classical antique sculpture. He only allowed students to explore abstraction once they had mastered these basic principles. This approach profoundly influenced his students, many of whom became successful artists in 20th century Turkey. They were instrumental in creating the many figurative monuments to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, which became prominent features of the national landscape and can still be seen throughout the country.

He also introduced cours de soir (evening classes), where students worked with life-size nude models - a significant development in Turkey, as the nude had only recently been allowed as a subject of study under Atatürk.

But Belling's influence met resistance from Turkish colleagues who wanted national artists to shape cultural identity. This led to splitting the sculpture studio in 1950, with Belling leading one section and Turkish artists leading another focused on abstraction. Belling then took a position at Istanbul Technical University, teaching there until 1966.

"For me - recalled daughter Elisabeth Weber-Belling - having been born and brought up there, it was home. And it was also home for my mother. And it became home for my father".4

Born in 1943 on the shores of the Bosphorus, Elisabeth Weber-Belling grew up in a world of multicultural richness: she spoke five languages. Her linguistic repertoire included German and French (from her Belgian-born grandmother), Italian (from her Istanbul-born Italian mother), Greek (from the Belling family's household staff), and Turkish, which she absorbed naturally through daily life and street play.

Indeed, it was home: her father's initial two-year contract turned into three decades in Istanbul. Belling built a life, a department and a legacy. Meanwhile, his memory was being erased in Germany - in 1944 his home and studio in Berlin-Lichterfelde were bombed, destroying many of his designs and original works.

Belling continued to teach at the Faculty of Architecture at Istanbul Technical University until 1965. After retiring, he returned to Germany in 1966 and settled in Bavaria, where he died in 1972. His daughter continued to manage his estate. In 2017, Berlin's Hamburger Bahnhof - National Gallery of Contemporary Art - hosted the artist's largest retrospective to date, with around 80 exhibits from the 1910s to the 1970s, finally restoring the respect and recognition he had long been denied.

Today, Rudolf Belling is considered one of the most important German sculptors of classical modernism. For many Turkish artists—whether they embraced his neoclassical ideals or moved toward abstraction—his presence marked a turning point. Rudolf Belling arrived as a foreigner, but his work helped shape the narrative of modern Turkish art.

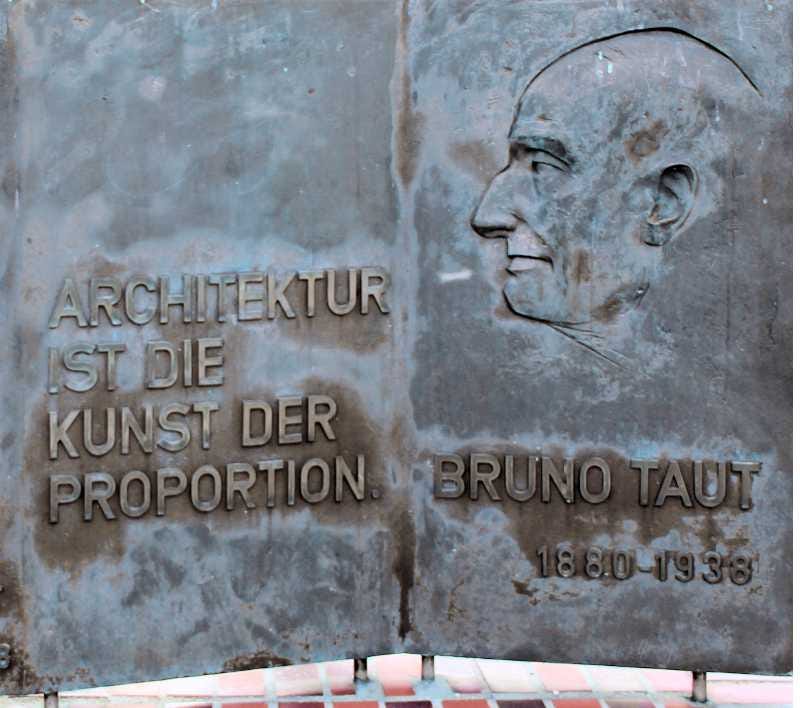

Bruno Taut

Bauhaus vision meets the Bosphorus

Here in Berlin, Bruno Taut (1880–1938) is something of an architectural hero. As the chief architect for the city’s Public Housing Savings, Building and Stock Company, he designed four of Berlin’s six UNESCO-listed housing estates during the Weimar Republic—vibrant, functional, coloured and green.

One of them, the Carl Legien Wohnstadt, is just 200 meters from my home. Every time I walk by, I’m reminded of Taut’s vision: to give workers not just roofs, but dignity: each apartment featured its own balcony, spacious inner courtyards, and communal areas designed not only for laundry but for socializing, all surrounded by abundant trees—even today, it remains an enviable and affordable place to live.

Given his progressive ideals, it’s no surprise that when the Nazis took power, Taut’s days in Germany were numbered.

The story of Bruno Taut in Turkey begins in 1936, not directly from Germany, but from Japan, where he’d been living and working after leaving Europe. His life there had been spartan and left him in poor health. Asthma would shadow him for the rest of his life.

Taut was renowned internationally. When Turkey needed someone to reform its architectural education, he appeared the best possible option. Taut was invited to head the Department of Architecture at the Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts (Güzel Sanatlar Akademisi). Taut arrived in Istanbul with high expectations riding on his shoulders, presented by the Turkish press as a “world-famous artist.” The country was counting on people like him to help reimagine its future.

Once in Istanbul, Taut got to work—not just teaching, but transforming the system. He streamlined the five-year curriculum, eliminated redundancies, and strengthened the connection between architectural education and industry.

He infused the Academy with a "Bauhaus spirit" through preliminary classes in fundamentals, unorthodox methods like group work and visual materials, and excursions to study real buildings and cities. His successful advocacy led to an expanded library and new resources. Yet, as with many visionaries, Taut met resistance—his bold ideas, coming from an outsider, challenged the status quo.

Despite tensions with the institution, Taut became chief architect for the Ministry of Education. In this position he designed schools, government buildings and university buildings.

In Ankara, Taut left his mark with the Atatürk Lyceum in Yenişehir, the Cebeci Middle School and the Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, which was completed in 1938 and is still considered one of the most beautiful buildings along Atatürk Boulevard. He also created a unique polygonal residence in Istanbul's Emin Vakfı Korusu - an architectural marvel suspended 17 metres above the forest floor.

In June 1938, the Academy of Fine Arts held a retrospective of Taut's work: a real moment of recognition. At the opening, Taut made a plea for openness in architectural education. He encouraged students to respect tradition while embracing the modern world - to find a synthesis between the two.

Later that year came the event that would prove too much for him. After Atatürk's death, Taut was commissioned to design the leader's catafalque - the ceremonial platform on which his body would lie in state. Despite being weakened by asthma, Taut worked in freezing conditions to complete the task.

The effort proved fatal. He fell ill and never recovered. Bruno Taut died penniless on 24 December 1938. While his colleagues at the Academy paid for his funeral, the Turkish state honoured him with a full state funeral. To this day, Turkish architects and Japanese visitors make pilgrimages to pay their respect to his grave at the Istanbul's Edirnekapı Cemetery.

Taut's time in Turkey lasted just two years - but his influence was far-reaching. He wasn't universally popular. His reforms weren't always implemented. But his insistence on a humane, culturally grounded modernism left a lasting impression.

And while Taut may be better known in Berlin or Tokyo, in Turkey he remains a figure of transformation - a man who tried to build a bridge between old and new, East and West, tradition and progress.

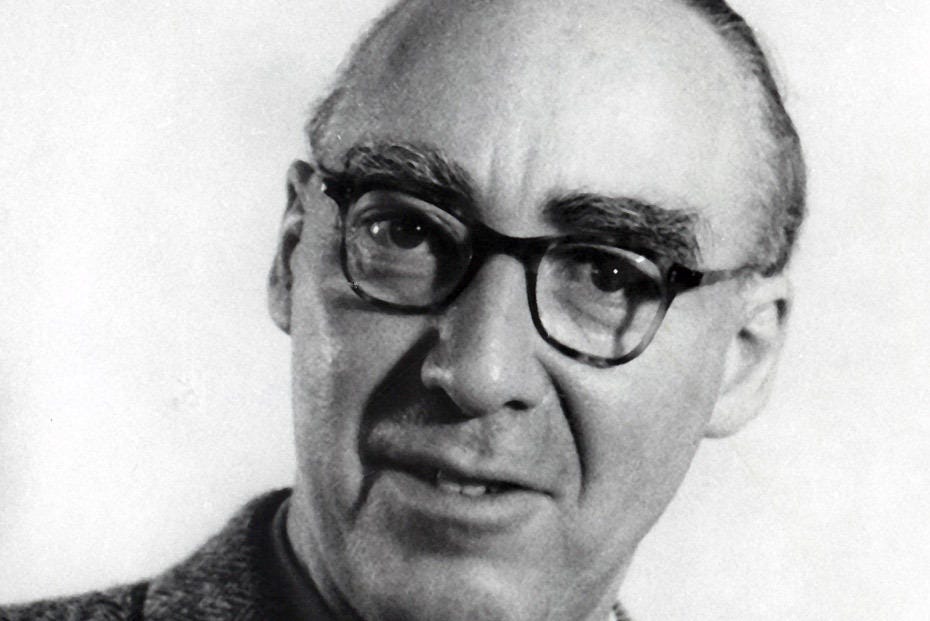

Alfred Heilbronn

Botanist in exile, roots in two worlds.

Alfred Heilbronn was born in Bavaria in 1885 into a wealthy Jewish family: he soon left home for Munich to study science. By 1909 he obtained a doctorate in botany, physics and chemistry, and a few years later he became an associate professor of botany at the University of Münster, where he planned and directed the botanical garden.

In 1913 he married Magda Detmer, an art historian and teacher, who converted to Protestantism to please her family. They had two children and settled in a large house in Münster, where a life of intellectual pursuit and stability seemed to lie ahead.

But like so many others, Heilbronn's world changed violently in 1933. Although his Jewish identity had never been central to his sense of self - a fully assimilated life in a Protestant household - he was suddenly classified and persecuted under the new Nazi racial laws.

And like many others, thanks to the intervention of Philipp Schwartz's Emergency Association of German Scientists Abroad, Heilbronn received an invitation to teach in Istanbul. In 1935 he founded the Pharmacological-Botanical Institute at the University of Istanbul, which is still faithful to his teachings and uses his materials.

Heilbronn immersed himself in Turkish life, learning the language and continuing his research into medicinal plants and the flora of the Marmara region. His children studied medicine in Istanbul and he became a Turkish citizen in 1946. Two years later he married his second wife, the Turkish professor Fatma Mehpare Başarman.

Although he returned to Germany in 1955, his roots had long since grown deep into the soil of Istanbul. His most beloved legacy by locals of all ages was the Alfred Heilbronn Botanical Garden, a jewel in a splendid location overlooking the Bosphorus, terraced behind the majestic Süleymaniye Mosque.

Sadly, the beautiful garden founded by Alfred Heilbronn - once tended with love, knowledge and a deep sense of purpose - has become a symbol of how quickly things can change. Atatürk's Turkey, with its ambition to build a secular, European-style democracy open to science and ideas, now survives mainly in the hearts of those still fighting for it.

In 2015, the garden was quietly transferred to the authority of the city's religious administration, the Mufti. The move, exposed by members of the opposition, set off alarm bells - but little could be done. In 2018, the botany department of Istanbul University received a letter ordering them to vacate the premises within two months. The garden was closed and left to decay, presumably to be sold to a property investor - one of the many reshaping Istanbul's skyline with concrete and glass. Even the sign bearing Alfred Heilbronn's name has been removed, leaving only a rusted outline as a silent trace of the past. As of today, I don't know if the garden still exists.5

I know: this is a bittersweet end to this Exile story - and a warning. The incredible chapter in which Turkey took in exiled minds and built with them a new academic future is over. In the past fifteen years, another wave of brilliant students and scholars has left the country. This time their destinations are the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Canada.

History doesn't repeat itself, not exactly.

But it moves in cycles.

And it's up to governments,

to the people who run them,

to choose the direction of the spin.

Brain gain or brain drain?

This choice can shape the future of a country –or a continent– for generations.

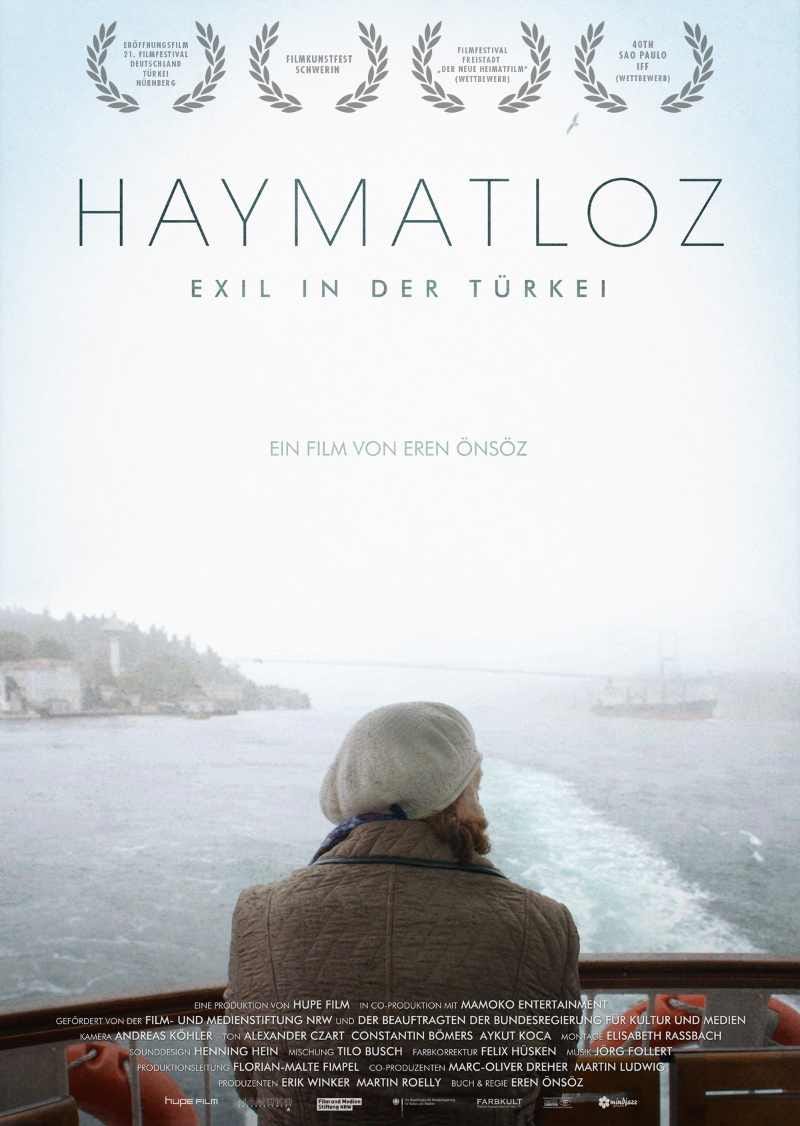

Epilogue: Haymatloz

In 2015, a German-Turkish documentary called “Haymatloz - Exil in der Türkei” (Haymatloz - Exile in Turkey) was released, one of those little gems that never become blockbusters but slowly find their way to their audience by word of mouth.

The documentary follows the journeys of five descendants - Susan Ferenz-Schwartz, Elisabeth Weber-Belling, Engin Bagda, Kurt Heilbronn and Enver Hirsch - as they revisit the places their families once called home.

Through personal stories, archival footage and reflection, the documentary explores themes of identity, belonging and cultural exchange. It is both a story of exile and an exploration of what makes a place truly home.

At the time of filming, Erdoğan had won another election and the youth of Istanbul were still recovering from the Gezi Park protests. The documentary addresses contemporary questions about the legacy of Atatürk's secular reforms in Turkey today. But it's not a political film - it's a tribute to the oldest idea that unites all sides of the Mediterranean: the idea that welcoming strangers and embracing diversity is not a burden but an investment - if you have a grand vision for your country.

Vanity Fair, March 31: “The Fascism Expert at Yale Who’s Fleeing America”; The Globe and Mail, March 28: “U.S. professors who left Yale for University of Toronto raise alarm about Trump crackdown”; Kyiv Independent, April 3: “Why I'm leaving Trump's America — historian Marci Shore”

Deutsche Welle, March 26 2025: Liebe US-Forschende: Willkommen in Deutschland!; SWR Aktuell, March 20 2025: Wegen Trump-Politik: Land will US-Wissenschaftler nach BW locken; Die Zeit, April 1 2025: Deutsche Wissenschaftler fordern Aufnahmeprogramm für US-Forscher.

Essential Bibliography: Ralf Roth, 2020: Flucht und Vertreibung von Sozialwissenschaftlern aus Deutschland und die Konsequenzen im 20. Jahrhundert (Flight and expulsion of social scientists from Germany and the consequences in the 20th century) Zeitschrift für Weltgeschichte. • Gordon Fraser, 2012: The Quantum Exodus: Jewish Fugitives, the Atomic Bomb, and the Holocaust. • Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland - Second World War, 2001: Die Schweiz und die Flüchtlinge zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (Switzerland and the refugees at the time of National Socialism) • Melda Keser, Tekirdağ, 2024: Philipp Schwartz: Seine Beiträge zur Türkei und zu deutschen Exilanten (Philipp Schwartz: His contributions to Turkey and German exiles) • Michael Egger, 2010: Österreichische WissenschaftlerInnen in der Emigration in der Türkei von 1933 bis 1946 (Austrian scientists in the emigration in Turkey from 1933 to 1946) • Christopher Kubaseck, Günter Seufert, 2016: Deutsche Wissenschaftler im türkischen Exil: Die Wissenschaftsmigration in die Türkei 1933-1945 (German scientists in exile in Turkey: Scientific migration to Turkey 1933-1945).

From Documentary film "Haymatloz", 2014

September 2020, ISTANBUL'S FIRST BOTANICAL GARDEN: EXPERIENCE GERMAN-TURKISH HISTORY WITH ALL YOUR SENSES (German), treffpunkteuropa.de

Also worth reading as a follow-up to this story: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/14/opinion/yale-canada-fascism.html?smid=bsky-nytimes

When I write about the past, I always keep an eye on the present and the future. While we Europeans often dismiss Brussels-led initiatives as mere "talk", the relaunch of the "Choose Europe for Science" plan announced in early May carries real weight - it is much more than a list of principles. The €500 million package for 2025-2027, complemented by super-grants and relocation bonuses to attract global talent, deserves serious attention. It creates healthy and promising mechanisms that France and Germany, in particular, will use effectively. If it were up to me, we should extend this approach by offering a "relocation package" to Wikipedia (see: https://www.thefp.com/p/trump-prosecutor-threatens-wikipedia).