Potsdam 1945: The Seventeen Days That Shaped the Post-War Order

In July 1945, the three Allied powers met in Potsdam near Berlin to shape the post-war world. Their decisions redrew Europe's map, laid Cold War foundations, and determined Japan's fate.

Berlin's rubble-strewn wasteland, the largest necropolis in Europe, defies description in its gruesome uniqueness. Only someone with strong nerves could witness all this and begin to comprehend what happened here. [...] Rubble, hunger, shards and poverty – that is Berlin.— From the diary of Karl Deutmann: “Destroyed Berlin 1945”, 11 July 1945

In July 1945, the German capital lay in ruins. Buildings stood like skeletons. Bodies still lined the sidewalks. Berlin had become an urban cemetery. Some graves had crosses and names. Others just helmets on wooden stakes.

Karl Deutmann, a resident of the Adlershof suburb, ventured into the city with his wife. What he witnessed seemed beyond comprehension. "Ghostly forms of former houses," he recorded in his diary. "Ghostly streets. Ghostly districts."

But these weren't ghosts wandering through Berlin. They were people. Hungry, desperate people digging through rubble. Scavenging for food, for wood, for anything to sell. Many were forced by Soviet soldiers to clear the streets, making them passable again. Others, especially women, spent their days searching for water or doing laundry wherever possible, sometimes using only street hydrants.

The sanitary conditions were appalling. The air was thick with the stench of decay. Warning posters appeared everywhere: "Do not drink unboiled water!" "Cook all meat thoroughly!" Contamination threatened from all sides. Rats bred at an alarming rate. Medicine remained in short supply. Alcohol was harder to find.

Food came only through strict rationing. People stood in lines for hours just to receive a loaf of bread or a simple bowl of soup. The black market flourished. Cigarettes became more valuable than currency. Desperate city residents gathered whatever valuables they had and traveled to rural areas, hoping to exchange them for potatoes or eggs. They named these desperate journeys Hamsterfahrten — hamster trips.

Berlin wasn't divided yet. The city was fully under Soviet control. Slowly, they began restoring basic services. Trams and buses creaked back to life. Some water returned. Lights flickered on in certain areas. Through this broken city flowed an endless stream of refugees. Hundreds of thousands—sometimes over half a million in July alone. They couldn't stay; there was no room. So they kept moving, like human water through a shattered pipe.

The violence persisted. Soviet soldiers continued to rape German women—at least one hundred thousand victims. Hospitals documented a surge of unwanted pregnancies that August. This was Berlin. This was the defeated heart of Nazi Germany, where the world's victors were supposed to meet to redraw maps and determine fates.

A More Suitable Venue

Even for propaganda’s sake, it was impossible. So the Soviets picked another place. Potsdam — quieter, safer, less destroyed.

Potsdam was the former royal seat of Prussia. There, in the Neuer Garten district, stood a peculiar residence — built in Tudor style in 1912. It was commissioned by Kaiser Wilhelm II: The German Emperor was a Grandson of Queen Victoria. He built it as a gift for his son. Today, we know it as Cecilienhof. British architecture. German royalty. Soviet security.

Two images are forever tied to the Potsdam Conference.

One: the palace itself, with a bright red star made of geraniums planted by Stalin’s security chief. A Soviet signature, subtle as a brick through a window.

Image two: the round table where three men, plus counselors, military attendants, ambassadors, would reshape the world. Round, of course - no one gets the head seat at a round table. But this table also had its Soviet signature: The photos appear black and white, but that table was blood red.

Stalin knew theater. For several days, he wore a dazzling white uniform for the cameras. While Truman and Churchill wore gray and beige, Stalin stood out like a spotlight in the dark.

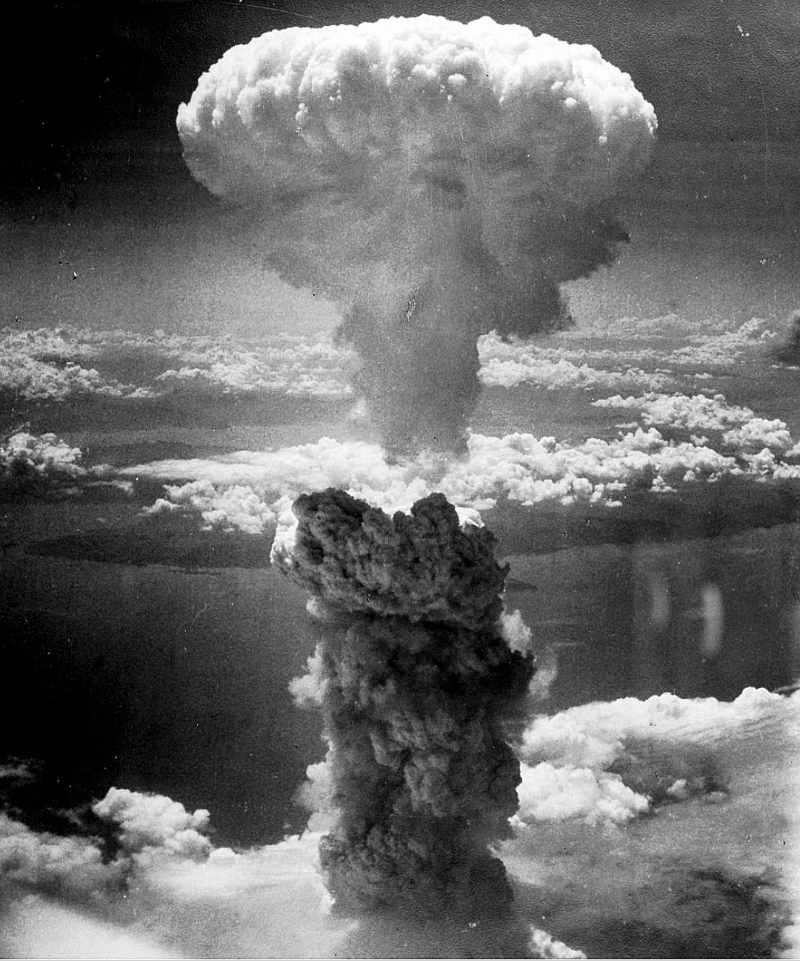

But there's a third image rarely connected to Potsdam: the shadow of a mushroom cloud. During these very days, the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was taking shape.

This is the story of those seventeen days that reshaped the world. And of a ruined Berlin watching from a distance as three countries and a handful of men redrew its destiny.

The Men at the Table

Three men sat down to divide the world. One was a veteran. Two were rookies.

Joseph Stalin had been in power for 23 years and 3 months. He'd orchestrated purges, engineered famines, and weathered the greatest war in human history. He knew exactly how this geopolitical game worked. He also knew exactly what he wanted.

Harry S. Truman had been president for just three months. He'd stepped in suddenly after Roosevelt's death in April 1945. Poor Harry had been kept completely in the dark about everything. The Yalta agreements? News to him. He'd stumbled across whispers of something called the "Manhattan Project" as a senator. But only after becoming president did Henry Stimson sit him down for the full briefing. No wonder he tried to delay the Potsdam Conference as long as possible. He needed time to catch up.

Winston Churchill showed up for the opening act. But democracy had other plans. On July 28th, halfway through the conference, he was gone. The British people had spoken. They wanted change. The Labour Party had won the general election. So Clement Attlee took his place. New prime minister. Quiet, modest, precise. No fireworks—but no change in policy either.

France? Not invited. Poland? The country they were all discussing? Also not invited. Truman dismissed Charles de Gaulle as the head of a "minor power." France would later accept the conference's decisions—grudgingly.

Each leader arrived with their own pressing concerns.

Britain was fighting for economic survival. The war had nearly bankrupted them. They needed financial aid, not lectures about democracy. America wanted to end the Pacific war quickly, then focus on rebuilding Europe while preventing Soviet expansion west of Moscow. The Soviet Union craved security above all. They'd been invaded twice in 30 years and were determined: never again. They demanded buffer states with friendly governments firmly under their control. Germany had reduced Soviet cities to rubble. Now Stalin wanted compensation—he took everything: machinery, materials, even furniture. Entire Soviet army divisions became demolition crews, stripping buildings down to the light bulbs.

Despite these tensions, how did the conference actually begin? Surprisingly, with optimism. With true smiles. Toasts. Group photos.

They had just defeated Nazi Germany. The ultimate evil was vanquished. They were the victors who had saved the world together. Surely they could work out how to divide the spoils peacefully. None of them realized they were laying the groundwork for the Cold War.

How tragically mistaken they were.

Ghosts at the Table: Versailles 1919 and Munich 1938

Potsdam began with smiles. But two ghosts were already in the room: Versailles, 1919 and Munich, 1938.

The first ghost — Versailles — haunted everyone. The treaty that was supposed to make the world safer had instead paved the road to World War II.

John Maynard Keynes, the British economist, knew it. James Byrnes, now U.S. Secretary of State, knew it too. They were there in 1919. Both warned: don't repeat the mistakes.

The reparations had been insane. Germany couldn't pay them. The attempt had destroyed their economy, crashed all of Europe's economy, and forced the U.S. to pour in money. Worse, it fed a dangerous narrative — that Germany was unfairly treated.

The borders made no sense. They'd created countries like Yugoslavia or Czechoslovakia that were either economically doomed or ethnically explosive. Sometimes both.

Stalin had his own take on Versailles. His problem? Too many small countries got a say. "Small states aren't virtuous just because they're small," he argued. Only the big powers should decide the world's fate.

And then there was the narrative problem. After World War I, German generals could claim they'd never really lost. "We were stabbed in the back at home!" Perfect fuel for revenge fantasies. At least that wouldn't happen this time. Berlin was a pile of rubble. Nobody could claim the Wehrmacht was "undefeated in the field."

But that second ghost — Munich, 1938 — brought even more tension.

Back then, Britain and France tried to appease Hitler. Chamberlain waving his piece of paper. "Peace for our time!" It was the great betrayal. They gave Hitler the Sudetenland. In return, he gave them war.

Potsdam's leaders didn't forget. They weren't about to appease another aggressive power. And in 1945, the fear wasn't Germany anymore. It was Stalin. They were terrified of appeasing another expansionist dictator. The West wanted to stop him from gaining too much. From turning Europe red — without firing a shot. So Potsdam became a balancing act.

How to contain Soviet power without breaking the fragile alliance that had just defeated Hitler? The fear of both ghosts shaped every decision, starting with reparations.

Each power would take them from its own occupied zone. No Versailles-style punishments across Germany. No chance for Stalin to drain the whole country. It made financial sense—but it had an unintended consequence. It split Germany economically. And economic divisions quickly become political ones.

Poland was another flashpoint. The Red Army was already there. The West pushed for free elections but failed. Truman was furious about the forced expulsions of Germans from territories that suddenly became Polish. Truman understood the reality: "Forcing Soviet compliance would require military action. That's not in the cards."

During this period, a quiet strategy began to form: containment. George Kennan, a brilliant U.S. diplomat, argued that the Soviet system would eventually collapse—not from external force, but from within. The West simply needed patience. The strategy was clear: Build up Western Europe. Make it strong, prosperous, and free. Prevent Stalin from expanding his influence. Then watch the USSR crumble under its own contradictions. It would only take... forty-five years.

But even among the Western Allies, divisions emerged. The U.S. and U.K. had different goals.

Truman didn't want a permanent American presence in Europe. He planned to help rebuild, then withdraw. Do the job, hand over responsibility, and go home. Churchill was horrified. Without American troops, Europe would lie defenseless against Soviet forces. He could almost visualize them advancing to the English Channel.

Economic issues compounded the tension. The U.S. had established Bretton Woods, shifting global finance from London to New York. Keynes called it a swindle—to him, it signaled the end of Britain's empire and America's ascension.

Truman and Churchill also clashed over France. Truman dismissed De Gaulle as representing a "minor power." Churchill disagreed, having collaborated with the French and believing they deserved representation.

Even media strategy divided them. Churchill favored transparency with the 180 journalists stationed outside Cecilienhof. Truman aligned with Stalin's preference for secrecy. Despite the tensions, Truman personally liked Stalin. He found him charming—"Uncle Joe" seemed reasonable face-to-face.

But personal rapport couldn't overcome geopolitical realities. The forces driving these three powers apart proved stronger than any handshake. Those seventeen days were compromised from the beginning. Not because the participants were malicious, but because they were constrained by history.

The ghosts of Versailles and Munich prevented genuine peace. They could only establish a new kind of conflict: cold, but equally challenging. And enduring. The Cold War was born in Potsdam.

July 15, 1945: Arrival

“The requisitioning continues. Apartments in Dahlem, apartments in Wannsee. Entire districts. Evacuation within hours… It doesn’t matter who you are — Nazi friend or Nazi opponent — if you have to go, you go.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Berlin, July 15, 1945 “Schauplatz Berlin: 1945-1948”

In Berlin, the war was over. But the chaos persisted. The Soviets continued evicting civilians at will—clearing out apartments, villas, and entire neighborhoods. Doors slammed shut on families with only minutes' notice. Rich or poor, guilty or innocent—no one was spared. As resistance heroine Ruth Andreas-Friedrich noted in her diary, people consoled themselves that this was merely the aftershock of war. The looting, rapes, and evictions would surely end soon:

"This evening, the radio announced that Stalin, Truman, and Churchill have arrived in Berlin for a joint conference. While this doesn't change anything about the requisitioning, it does help lessen our disappointment. We must view everything that has happened until now—the rapes, the looting, the requisitioning—as aftereffects of the war. The meeting of the Big Three will establish order. It will prepare the ground on which good things can flourish." — ibidem

Before the Potsdam Conference began, the Red Army systematically cleared Potsdam of almost all German inhabitants. Families who'd lived there for generations received just hours' notice. Pack what you can carry. Leave the rest. Make room for the Allies. They divided Potsdam and neighboring Babelsberg into American, British, and Soviet sectors. Seized the villas. Refurnished them. And of course, wired them with hundreds of hidden listening devices.

Truman and Churchill arrived two days ahead of schedule—just enough time to settle in.

Truman had journeyed aboard the USS Augusta before flying in from Belgium. He landed at Gatow Airfield in Berlin's western outskirts, where he was greeted with honor guards and meticulously planned ceremony. The U.S. President’s Logbook reads like a real estate brochure:

“Babelsberg lies along winding Griebnitz Lake… a pleasant climate in July… The house at No. 2 Kaiserstrasse — now the ‘Little White House’ — sits by the lake, surrounded by trees. Beautiful gardens reaching down to the lake. Formerly occupied by the head of the German movie colony, who is now with a labor battalion somewhere in Russia." — Log of President Harry S. Truman's Trip to the Berlin Conference, Diary Notes and Letters, Harry Truman Library

The entry ends with a couple of complaints. Nice enough place, but:

“…like most European homes, the bathroom and bathing facilities were wholly inadequate. Nor was it screened, so the mosquitoes gave us a "working over" during our first few nights there until the weather had cooled somewhat." — ibidem

But the logbook omitted an ugly story. The hoise belonged to the Müller-Grote family. In May 1945, Soviet soldiers didn't knock politely and ask for the keys. They broke down the door. They plundered everything. They raped several women in the family—in front of their parents and children. They beat the elderly parents. The family's belongings were smashed, looted, tossed into the forest, or used to fill bomb craters. The Soviets, assuming Truman would bring his own furniture, destroyed everything.

Only later did they panic and refurnish the house—quickly. Truman's staff never knew the truth. And in his memoir, the President even repeated the lie that the villa's former owner had been "sent to Siberia." In 1956, Dietrich Müller-Grote—the son of the owners—wrote to Truman, gently correcting the record. The family, he explained, had been living just half a kilometer away. In squalor.

While staying at the villa, Truman had hundreds of pages to read. Briefings on tactics. Meetings with advisors haunted by Versailles and Munich. He wrote to his mother with brutal honesty: "I'd prefer not to go at all, but I have to."

Winston Churchill arrived the same day. His mood was equally dark. The British election was in its final stages. The polls looked grim. He could feel power slipping through his fingers. This might be his last performance on the world stage. And he knew it.

Stalin kept them waiting. Of course he did. He arrived 24 hours late on July 16th. "Delayed by the Chinese," he claimed—a move to remind the others who controlled the stage. He traveled in an armored train with bulletproof windows. Fifteen thousand NKVD soldiers protected the rail network—twelve to fourteen men per kilometer. When he finally reached Cecilienhof Palace, he set up his office in the eastern wing. It was clear, before a single word had been spoken: this house belonged to Stalin.

July 16, 1945: A destroyed capital in Europe, the promise of worse destruction tested in America

Babelsberg. A leafy, quiet suburb between Potsdam and Berlin. It was peaceful then, just as it is now. President Truman, ever the early bird, started his day with a walk. Breakfast at 8, like clockwork.

At 11 AM, Winston Churchill knocked on the door. He brought his daughter Mary, Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, and Sir Alexander Cadogan. They met for the first time in the “Little White House”. Afterwards, they shared lunch. Stalin hadn’t yet reached Potsdam. The official talks were pushed to the next day.

So Truman used the afternoon to take a drive through Berlin. At 4:57 PM, the motorcade moved along Wilhelmstrasse, past the wreckage of the Nazi regime main sites. The balcony of the New Reich Chancellery — where Hitler once roared at crowds — was now broken stone. Truman stood there for a few minutes. Taking it in.

“It is just a demonstration of what can happen when a man overreaches himself.” […] “I never saw such destruction… I don’t know whether they learned anything from it or not.” — Truman’s Diary, July 16, 1945

The drive continued. Ruins everywhere. The Tiergarten. The Reichstag. The Adlon Hotel. The Brandenburg Gate. The Foreign Office. The Olympic Stadium. The Funkturm. The Victory Column. Once icons of a great capital. From the Presidential logbook: "Every building we saw was either badly damaged or completely destroyed."

This was Berlin. Capital of the Thousand Year Reich. Four and a quarter million people used to live here.

“This once beautiful city… now wrecked beyond repair.” […] “A distressing example of what happens when people lose their moral compass—and follow false prophets.”

But the buildings weren't the worst part.

"More moving than the destroyed buildings was the long, never-ending procession of old men, women and children".

They drove along the autobahn. Along country roads. "Wandering aimlessly and probably without hope." Small children in their arms. Meager belongings in pushcarts. Everything they owned in the world.

“In two hours, we saw evidence of a great world tragedy — the disintegration of a highly cultured and proud people.” — Truman’s Diary, July 16, 1945

Later that day, Churchill also drove through Berlin. Their motorcades crossed briefly under the linden trees.

Thousands of kilometers away, in the New Mexico desert, the first nuclear bomb had just been tested. It exploded at 5:29 AM local time. Truman got word — a coded message: the Trinity test was successful. Truman and Churchill made a decision. They would tell Stalin about their "new super weapon." But carefully. Casually. Without using the word "atomic." They had no idea Stalin already knew. Soviet spies had been watching the Manhattan Project from the beginning.

The Conference Begins: Handshakes and Hard Truths, July 17-21

“A few minutes before noon, I looked up from my desk and saw Stalin standing at the gate.” […] “He extended his hand and smiled. I did the same.” — Truman’s Diary, July 17, 1945

Truman met Stalin for the first time in the garden of the Little White House. They shook hands and sat down. Truman admitted he liked Stalin:

“He knows what he wants. He’ll compromise if he must. He looked me in the eyes.” […] “I was impressed. He was extremely polite.” But years later, Truman saw it differently: “I was an innocent idealist.” […] “He was an unscrupulous Russian dictator. But I liked the little son of a bitch.”

Maybe he should’ve listened more closely. When an American ambassador praised the Red Army for taking Berlin, Stalin simply replied: “Tsar Alexander made it all the way to Paris.” A subtle warning and a reminder. Russia plays the long game.

5:10 PM, 17 July 1945. The Berlin Conference officially opened. At Stalin’s suggestion, Truman was named chairman.

Truman came prepared. He'd studied hundreds of pages. Consulted experienced staff. His first priority: avoid "the mistakes of their predecessors 25 years earlier" in Paris. No more Versailles disasters. This time would be different. Truman’s first proposal: a new Council of Foreign Ministers — with the UK, USA, USSR, China, and France — to draft postwar treaties. Stalin raised an eyebrow: “But these are European problems. What’s China got to do with it?”

Germany came next, with a foundational question: What exactly was Germany now? Where did it begin? Where did it end?

The Allies agreed to use 1937 borders as a starting point — but just that. A starting point. Defining Germany in 1945 was like trying to draw a blueprint after an earthquake. Each of the Big Three had a different vision. The house was broken, and no one could agree on how to rebuild it — or even where.

Out of this chaos came the famous “Four Ds” — the basic pillars of the plan: Demilitarization: No more Wehrmacht. No more weapons factories. No more military anything. Germany would never threaten peace again. Denazification: Erase the Nazi Party. Re-educate the people. Bring war criminals to justice. Democratization: Transform Germany into a proper democracy. Political parties. Free elections. The whole democratic toolkit. At least for one side of it. Decentralization: Break up the monopolies. Smash the cartels. Power to the Länder, not a strong central government.

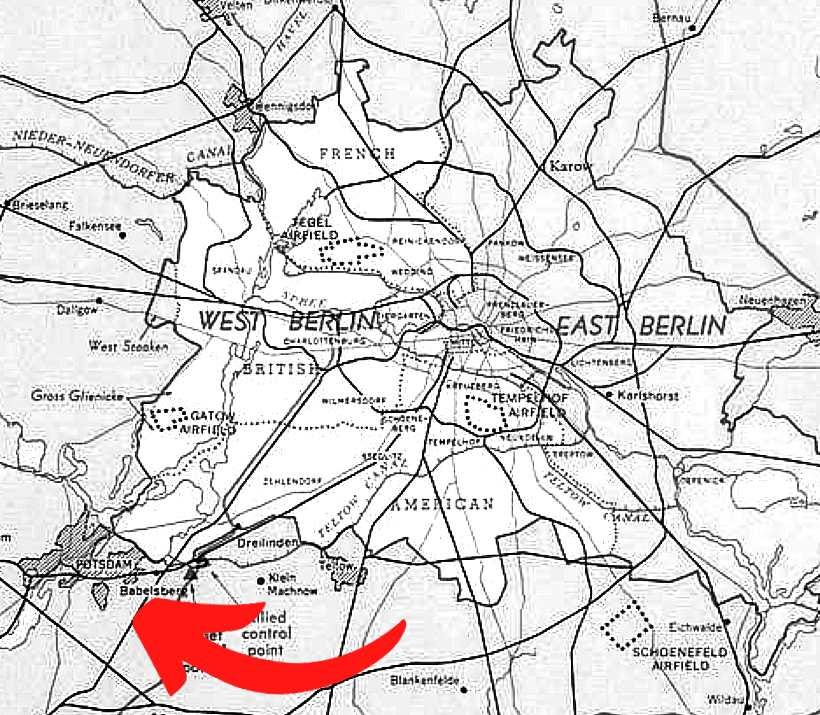

What about the map? Germany was sliced into four zones — American, British, Soviet, and French. Even Berlin, deep in Soviet territory, was divided into four sectors. In theory, Germany would remain a single unit — run jointly by the Allies. In practice? The cracks were already forming.

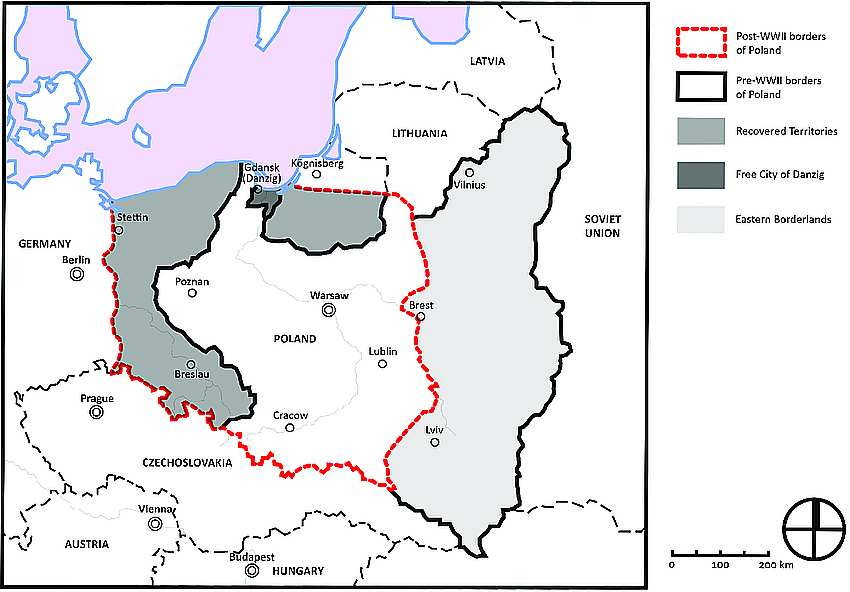

One of the biggest cracks was the eastern border. The Allies provisionally recognized the Oder–Neisse Line as Poland’s new western edge. This meant huge chunks of former German territory — Silesia, Pomerania, East Prussia — were handed over to Poland and the USSR. Poland itself had been pushed west, its eastern lands swallowed by the Soviet Union. A whole country had shifted sideways on the map.

And with that came one of the largest forced migrations in human history. The official language was cold: “The orderly and humane transfer of German populations.” The reality was ethnic cleansing: over 14 million people uprooted from their homes. Centuries of life erased.

Then came the elephant in the room: reparations. The Soviets wanted a lot. They’d lost more than 20 million people. Their cities were in ruins. But Truman had no intention of bankrupting Germany again — like after World War I.

The compromise: each country would take reparations from its own occupation zone. The Soviets would also get extra industrial equipment from the Western zones — in exchange for goods like coal and oil. But this approach only deepened the East–West divide. One American noted the Soviets were “taking everything they could get their hands on.”

On July 19, Churchill brought up Yugoslavia. Tito’s government had no free elections, no free press.: “It’s starting to look like a fascist regime,” Stalin brushed it off: “Let the Yugoslavs explain themselves”.

But if the talks were tense, the evenings were another matter. Dinner diplomacy had its own rhythm.

On July 20, it was Truman’s turn to host. He sat between Churchill and Stalin. And a house concert for them. Sergeant Eugene List played a Tchaikovsky arrangement for Stalin. Stalin stood up, shook his hand, toasted him. Then he asked for more. Later, List played the Missouri Waltz for Truman. Home sweet home. Wine bottles exchanged for vodka bottles. Toasts all around. Civilized men solving the world's problems over good music and strong drinks.

Meanwhile, just miles away in Berlin — the hunger was unbearable.

“Our neighbor, whose husband was taken away in May and who was left alone with five children, lies in bed and doesn't get up again. 'Because of hunger,' she whispers weakly." […] “What does a mother do when she receives only three hundred grams of bread per day? She divides it among her children and satisfies herself by watching them eat.” […] ”In Potsdam, the conference of the Big Three is in session. The entire area is cordoned off. No German may set foot in the sacred negotiation districts. May the grass grow in them—may it grow before the cows have perished.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Schauplatz Berlin Diaries, July 19, 1945

July 22–29: Redrawing Europe. Deciding Japan’s Fate. A New PM Walks In.

On July 22, Stalin made an announcement: Soviet troops had started pulling out of Austria. The country, too, was to be divided in four occupation zones, as its capital Vienna. Truman and Churchill welcomed the move with relief. ut while Stalin was being cooperative in Austria, things were getting messy elsewhere.

The Big Three kept talking about the Yalta Declaration, which was a promise about free elections and press freedom in liberated countries. But the Soviets pushed back — proposing their own rules for Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary. Also for Italy. The Soviet sphere of influence was starting to take shape — one memorandum at a time.

The hottest issue was still Poland. Not just where the borders should fall — but who should govern. In London, the Polish government-in-exile was still hoping for a role. The West wanted free elections. The Soviets wanted something else. But while the big guys talked in Potsdam, Stalin was busy making facts on the ground. American diplomats were getting reports. Civil liberties crushed. Mass arrests by Soviet secret police. What could they do? Risk a major confrontation with the Soviets? Not likely. Poland was abandoned. Again.

"[...] I wish that instead of mumbling words of official optimism we had had the judgment and the good taste to bow our heads in silence before the tragedy of a people who have been our allies, whom we have helped to save from our enemies and whom we cannot save from our friends." - George Kennan, the US chargé d'affaires in Moscow

July 23rd sealed another fate: Königsberg - the old capital of East Prussia, birthplace of Immanuel Kant - was handed over to the Soviet Union. For Stalin, this was gold. A strategic Baltic port that didn't freeze half the year like others. Perfect for military and commercial ships. Today? It's the most dangerous border Europe shares with Russia. History has a way of coming back to haunt us.

July 24th Truman told Stalin about America's "new super weapon." The atomic bomb, fresh from testing. Stalin played it cool. "That's good," he said. "We'll use it against Japan." Stalin already knew. Soviet spies had been busy. His casual response was pure theater. Stalin saw this as atomic blackmail. His paranoia went through the roof.

On July 25, the U.S. issued a formal order: Prepare the atomic bombings of Japan. The war needed to end quickly. Avoid a bloody invasion of the home islands.

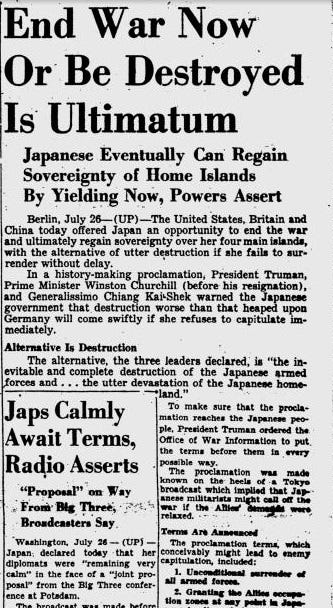

July 26th brought the Potsdam Declaration. Truman, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek (joining by radio from China) delivered Japan's ultimatum. Surrender unconditionally. Or face complete destruction. They didn't mince words. Look at Germany, they said. See what happened with their "senseless resistance"? Don't make the same mistake. The message went out everywhere. Shortwave radio. Medium-wave transmitters. Millions of leaflets dropped over Japan. The whole world was watching.

On July 27, Japan answered with a single word: “Mokusatsu” — “to kill with silence”. The word carried layers of meaning. Ambiguous. Noncommittal. But the U.S. translated it as one thing: Rejection. Truman took it personally. “They told me I could go to hell,” he recalled later. That single word sealed Japan's fate

While all this drama unfolded, the Potsdam Conference hit a snag. Churchill had to leave. British voters had spoken. His Conservative Party lost the election. Out went the great wartime leader. In came Labour's Clement Attlee and Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin. New faces at the table. Same problems to solve.

Truman wrote he felt sorry for Churchill…but not too sorry. He believed it might be easier to deal with Stalin without him. Stalin, on the other hand, was shaken. He respected Churchill — he knew how to read him. Now he had to face strangers. He reportedly muttered about “rotten democracies”. Molotov reportedly added: “That is the problem with elections. One never knows how they’ll turn out.”

In Berlin, even civilians felt the shift:

“While I'm busy with pots, poker, and cooking spoon, Heike (a friend of Ruth) comes running in. "They've ousted Churchill," she says. "And Eden. Attlee is supposed to have become Prime Minister." I drop the cooking spoon. All this in the middle of the conference? "Bottomless ingratitude!" "Not ingratitude at all," Andrik (Ruth partner) chimes in from inside. "Just proof of how objectively the English conduct politics. For the war, Churchill was their best man. For peace, especially if it's to be an allied peace, the Conservative Churchill has his dark sides. Attlee is a Labour man." — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Schauplatz Berlin Diaries, July 29, 1945

Toward the End — and a New Beginning

Maybe losing Churchill was too much for Stalin. Who knows? But the Soviet leader fell ill for a couple of days. The Big Three table sat half-empty. Main sessions were paused. But the work didn’t stop. Behind closed doors, the delegates kept hammering out details.

Germany. Poland. Greece, Spain, and Portugal with their neutral dictatorships. International waterways across the Black Sea, the Danube, the Rhine. The Kiel Canal. The international status of Tangier. Discussions about Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania dragged on.

Some chapters were closed. Many left hanging. But the clock was ticking. The world could wait no longer. The war in the Pacific had to end — fast.

July 29th. Stalin was still down sick. But big news came from across the Atlantic. The US Senate had ratified the United Nations Charter. Almost unanimously. A critical brick in the new world order.

Monday, July 30th. President Truman greeted military officials. Posed for photographers. Had another dinner with music. This time, Chopin selections. The President's favorites. A tribute to Poland. In the absence of the man who was occupying it - Stalin, still indisposed. But Truman was itching to leave. He wrote in his diary:

“Conference is delayed. Stalin and Molotov—he is sick. No Big Three meeting today. Sent Churchill a note of consolation. Regretted his failure to return. Wished him a long and happy life.”

He also knew big issues were still stuck:

“We’re at an impasse on Poland and its boundary… Russia and Poland agreed on the Oder and Western Neisse — a unilateral arrangement. I don’t like it… Roosevelt let Russia have twenty billion in reparations… experts say no such sum exists. I made it plain: the U.S. doesn’t intend to pay reparations. If the Russians strip the country and starve the people, we get nothing.” — Harry S. Truman, July 30, 1945

In these final days, Truman leaned heavily on General George C. Marshall. The Supreme Commander of US Armed Forces. The man Truman credited most for winning the war. Their conversations laid the groundwork for what would become the Marshall Plan.

The situation in Western Europe was dire. War had weakened everything. The political consequences were scary. Officials at the Little White House understood the stakes. Economic collapse in Western Europe meant communist influence spreading westward. Europe's new dominant power - the Soviet Union - would exploit the chaos. Great Britain was nearly bankrupt. France was hanging by a thread. The US Ambassador in Paris warned: without American coal and heating oil, France would fall to communism. Or maybe anarchy.

Flooding Western Europe with reconstruction money wasn't generosity. It was a geopolitical firewall against the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Berlin was drowning. Not in money - in people: soldiers, former forced laborers, KZ survivors, refugees. So many that Soviet authorities had to issue a "no entry" order. The city was literally imploding. Ruth Andreas-Friedrich witnessed the horror:

“Among the smart American uniforms, the first German soldiers appear — ragged and emaciated [...] Like walking ruins they stagger along. [...] Sometimes you see only torsos. Amputated almost to the hips… pushing themselves in margarine boxes on wheels. [...] ‘Heil Hitler!’ one wants to curse in furious compassion.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, July 30, 1945

July 31st and August 1st. The final sessions at Cecilienhof were the longest yet.

Still so much to cover. Major topics. Minor ones. Even Middle East issues. Everything had to go into the final declaration. Wednesday, August 1st, 10:30 PM. The thirteenth meeting of the Berlin Conference convened. Almost entirely devoted to studying and approving the final communiqué. Agreement came shortly after midnight.

At 12:30 AM, August 2, the Potsdam Conference was over.

That morning, Truman had a quick breakfast. At 8:15, he flew out of Berlin-Gatow airfield. The war was still on — but the diplomacy was done. In Berlin, the press celebrated.

“Big headlines in all newspapers. "The Potsdam Final Agreement. Common policy in all occupation zones. Agreement on the peace order in Europe." A weight lifts from our hearts. So no new war.” [...] “I can already see the dove of peace.”

"Don't see it too early," warns Frank. "Not everything in these resolutions will turn out as rosy as it appears in print. And regarding the article on reparations, territorial cessions, and the Russian western border, not to mention the repatriation of German minorities—meaning refugees from the ceded territories—I shudder when I think of their consequences.” [...]

“If this madness is implemented! Repatriation of German minorities from Poland! That means [...] eviction of millions of Germans. [...] – I remain silent, depressed. I hadn't imagined things this way. The Potsdam Agreement is beginning to seem sinister to me.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Schauplatz Berlin Diaries, August 4, 1945

August 6, 1945: The first atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Ruth Andreas-Friedrich processed the news:

“There we have it. Those who choose war will be destroyed by war. Not invasion, but atomic bomb. That terrible weapon, which has been rumored for weeks, was used yesterday against Japan. On the city of Hiroshima. With an explosive force two thousand times greater than the English ten-thousand-kilo bombs. It must have pulverized the city and its inhabitants. If Hitler had succeeded in creating such an instrument of destruction. Retribution weapon Number X. Unimaginable! But the grotesque thing about it is: three of the scientists who contributed to the invention are German emigrants. He could have played this murderous trump card if he hadn't—oh meaningful avenging Nemesis—blocked his own path through his racial hatred. New proof that dictators, at the decisive moment, destroy themselves through their own measures. Hiroshima is a pile of rubble. Perhaps tomorrow all of Japan will be.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Schauplatz Berlin Diaries, August 8, 1945

August 8, 1945: The Soviet Union declared war on Japan. August 9, 1945: The second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. August 14, 1945: Japan accepted unconditional surrender.

“The war in Japan is over” [...] Yesterday at two in the morning, the end of the war was announced [...]. The Japanese news agency reports that the War Minister, Korechika Anami, committed hara-kiri "to atone for his failures in fulfilling his duties as Minister of His Majesty." When will we finally begin to see heroism not in the destruction of life, but in its preservation.” — Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Schauplatz Berlin Diaries, August 16, 1945

September 2, 1945 — World War II officially ends.

But a new war was starting. A cold one. We thought the atomic threat would at least end the hot wars. It didn't. The Cold War didn't stop in 1989 either. Some wars never really end. They just change temperature.

Sources1

VIDEOS • DEU "Berlin 1945 Tagebuch einer Grossstadt teil 2", Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 2020 • DEU "Der Weg zur Potsdamer Konferenz 1945.", “Aus der Geschichte lernen” on YouTube, 2017 • ENG "The Potsdam Conference: 75 Years Later" Webinar. Presented by Michael Nyberg, Truman Library Institute, YouTube, 2020

DIARIES • DEU Andreas-Friedrich, Ruth: Schauplatz Berlin 1945-1948. • DEU Karl Deutmann: Aufzeichnungen aus dem Tagebuch, DHM-Deutsches Historisches Museum. • DEU Traudl Kupfer: Berlin 1945: Trümmer und Neubegin, BeBra Verlag 2025 • ENG Harry S. Truman: Log of President Harry S. Truman's Trip to the Berlin Conference, Diary Notes and Letters, Harry Truman Library

DOCS, BOOKS & PAPERS • DEU J. W. Brügel: "Die Sudetendeutsche Frage auf der Potsdamer Konferenz." (1962) • DEU Ruth Freydank: "Berlin als Theaterhauptstadt. Ein Kapitel Nachkriegsgeschichte”, 2000 • DEU R.S. Mackay: “THE STORY OF THE LITTLE WHITE HOUSE” Friedrich Neumann Stiftung, Berlin, 2023 • ENG Michael S. Neiberg: “Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe”. Basic Books, 2015 • DEU Internetredaktion LpB BW: "Neubeginn nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg" By Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg (LpB BW), last updated April 2025. • DEU "Das Potsdamer Abkommen. Dokumentensammlung." Staatsverlag der DDR, Berlin, 1975 (3rd revised edition 1980) • DEU Zofia Zakrzewska (Historisches Institut, Universität Warschau) in cooperation with Julita Gredecka, content editing by Prof. Jan Rydel ENRS: "Potsdamer Konferenz." Institut des Europäischen Netzwerks Erinnerung und Solidarität (ENRS), 2020 • DEU "LeMO Kapitel: Potsdamer Konferenz." Lebendiges Museum Online (LeMO) and "LeMO Zeitzeuge: Karl Deutmann." Lebendiges Museum Online (LeMO).