Soviet Photographers Who Captured the End of the War.

How Soviet photojournalists Yevgeny Khaldei, Timofei Melnik, and Ivan Shagin shaped the visual memory of victory in Berlin and Vienna—and why their personal stories matter.

World War II changed how war was seen — and how it was remembered.

For the first time, the conflict reached people not only through newspapers and government bulletins, but through a steady stream of radio broadcasts, newsreels in cinemas, and photographs printed in magazines or pinned to walls. It wasn’t “real time” — but it felt closer, more immediate, more personal than ever before.

In the First World War, images were rare, slow to arrive, often hidden in military archives. But by the 1940s, technology had caught up with history: cameras were portable, film could be developed quickly, and mass media had learned to speak in pictures. This war played out not only on battlefields — it was framed, captured, curated, and displayed. And there was something new in how those images were used. Censorship hadn’t disappeared; it had evolved. In its place came mass propaganda — polished, emotional, deliberate.

Media officers and political commissars knew exactly what they were doing: turning soldiers into symbols, ruins into warnings, and liberations into legend.

Photographers like Robert Capa, Lee Miller, Éric Schwab, and Margaret Bourke-White emerged as chroniclers of their time. Their images didn’t just survive the war; they shaped how we remember it. Especially in the West, where books, films, exhibitions etched their photographs into our shared memory of Europe in ruins. Margaret Bourke-White and Lee Miller (among others) became icons of women's self-assertion and role models for generations of younger women.

But this is only part of the picture. The western part.

In the East, too, the war was being recorded — frame by frame, word by word. Cameras clicked. Notebooks filled. The Red Army advanced with weapons, but also with lenses.

Writers like Vasily Grossman1 followed the front with typewriters and literary talent. And behind them, often just a step away from danger, were photographers and cameramen. Working fast. Working close.

Yet many of the people behind these devices remained anonymous. Even when their names reached us, they came with minimal biographies, either modest by nature or deliberately obscured by a communist regime that was intolerant of anything contradicting the official narrative.

Still, their images survived.

Some of them, too, became iconic.

What we see today of Berlin in 1945 — the rubble, the faces, the flags — comes from the work of several photographers. Many of these photos have been preserved, by the Berlin-Karlshorst Museum (former German-Russian museum) and private collectors dedicated to cataloging and remembering these images.

This week, in a Berlin spring that feels like 1945, we've had a chance to revisit these images. Some are rarely shown. Many cannot be reproduced here because of rights. But what matters is not only what they show — it’s who stood behind the camera. And their stories deserve to be told. Here, …

Jewgenij Chaldej: The photographer of liberation.

Jewgenij Chaldej was 28 years old when he took one of the most famous photos of the 20th century.

On May 2nd, 1945, the war in Europe was all but over. The Red Army had taken the Reichstag. Hitler was dead. Berlin had fallen. Khaldei arrived at the ruined building with a mission — not military, but symbolic. He carried a Soviet flag sewn from three tablecloths by his uncle. And he carried a camera: a Leica III.

His task was to capture victory.

A few days earlier, other Soviet soldiers had already raised a flag — on April 30th, Raqymjan Qoshqarbaev and his comrades had managed to plant it on the roof. But there were no photos. The scene was too dark. The moment passed undocumented. The flag was shot down.

On May 2nd, with the Reichstag now under firm control, Khaldei went up to the rooftop. He looked around and found three soldiers nearby. He asked them to help stage the shot. They weren’t famous. They just happened to be there. One of them was Private Aleksei Kovalev, 18 years old, from Kazakhstan. The others were Abdulkhakim Ismailov from Dagestan, and Leonid Gorychev from Minsk.

They climbed. They fixed the flag. Khaldei clicked the shutter. The resulting image — a Soviet banner billowing above the ruined Reichstag — became iconic. A symbol of victory. A monument in light and shadow.

But not everything in the frame was left untouched.

Back in Moscow, the editor of Ogonyok magazine spotted something. One of the soldiers — Ismailov — appeared to be wearing two watches. It looked like looting. That could mean execution. Khaldei was told to fix it. He scratched one watch out with a needle. Later, some claimed it wasn’t a second watch at all, but a compass. But the photo had already been altered. Khaldei also adjusted the smoke in the background — adding contrast, borrowing it from another negative to make the scene more dramatic.

He never hid the edits. For him, the photo wasn’t a lie. It was a symbol. Not of what happened exactly, but of what it meant. And it worked. The image was reprinted, over and over. The identities of the soldiers were often confused, changed, or deliberately rewritten. But the photo lived on.

It became the photograph of Soviet victory.

Behind the triumph of that moment—behind the weight of the flag, the grandeur of the shot—lay a personal story marked by deep scars.

Jewgenij Chaldej was born in 1917 in Yuzovka (now Donetsk) to a Jewish family. In 1918, during a pogrom carried out by White Army troops, his mother was shot while holding him in her arms. The bullet pierced her body and lodged in the baby's chest. She died; he survived.

Perhaps as a way to preserve his family's memory, the young Chaldej built a camera out of his grandmother's glasses and a cardboard box. With this homemade device, he began photographing both the horrors and triumphs of the wartime period.

He started working with the Soviet press agency TASS on October 25, 1936, at age 19. His father and three of his four sisters were murdered by the Nazis during the war.

He witnessed the aftermath of the massacre of 7,000 civilians in Kerch, Crimea, in 1942. During the Red Army's march to Berlin, Khaldei documented the liberation of Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary, and the capture of Vienna.

In Vienna, he entered a city broken but breathing, capturing Soviet soldiers against baroque façades and shattered landmarks. His photos from those days—of streets littered with rubble and silence, of St. Stephen's Cathedral still standing, of Belvedere, Heldenplatz, and the Parliament—speak less of victory than of hunger, absence, and the weight of survival.

Then, Berlin.

"I would have to say that many times my heart was broken. But I also witnessed greatness," he told Michael Specter in an interview in 1995. He photographed the Nuremberg trials and the Soviet offensive in Manchuria. Chaldej preserved 1,481 war negatives, which he kept in his Moscow apartment.

PHOTOGALLERY LFI LEICA FOTOGRAFIE INTERNATIONAL

PHOTOGALLERY DPA PICTURE ALLIANCE

PHOTOGALLERY INTERNATIONAL CENTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Khaldei continued his photojournalism career after the war as a TASS staff photographer until 1948, when he was dismissed during "staff downsizing." He then worked as a freelance photographer for Soviet newspapers, focusing on scenes of everyday life. In 1959, he joined the newspaper Pravda, where he worked until forced retirement in 1970.

Chaldej's international recognition came in the 1990s, when exhibitions of his photographs began appearing in the West. We can thank German photographer and gallerist Ernst Volland for Khaldei's Western rediscovery—after meeting Khaldei in 1991, Volland brought his work to international attention through exhibitions and books. In 2021, the Vienna Jewish Museum honored his photography of the city's liberation. In May 2025, Weimar is hosting photos from the collection of Ernst Volland.

Timofej Melnik: a witness among generals and common soldiers.

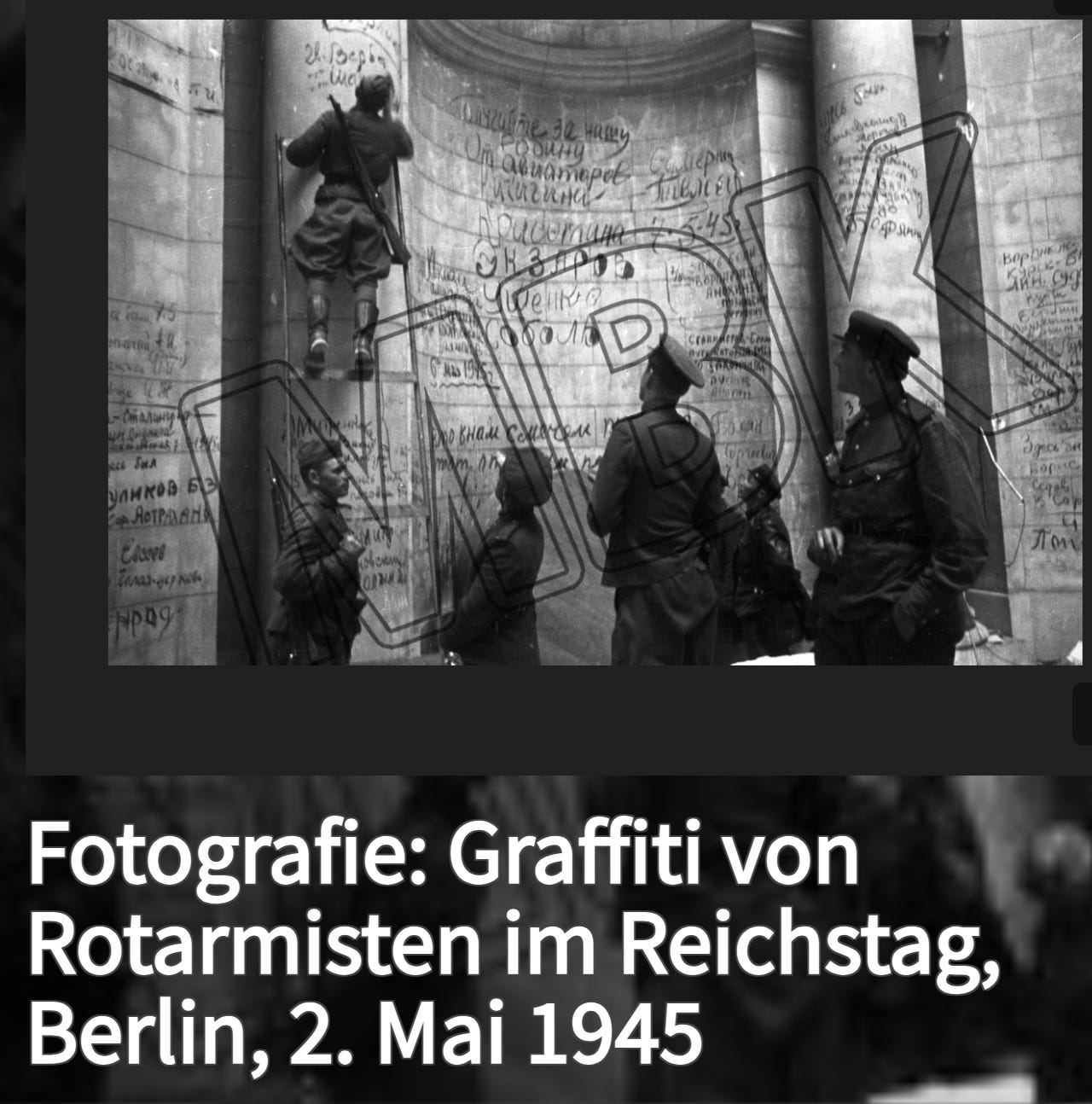

There's a photo. Scratched, grainy, timeless. A Soviet soldier, atop a long wooden ladder, scrawls his name on the wall of the Reichstag with a piece of chalk. Behind him, other soldiers and an officer with a cigarette in hand. The war is ending. History is being marked—literally—on the stone walls of the Nazi regime's heart. Even today, when you visit the Reichstag, you can see those names and graffiti.

That moment, and countless others like it, were captured by the lens of a man few knew by name, but whose eye helped define victory for a generation: Timofej Nikolayevich Melnik.

Born in 1911 in the Kursk Governorate, in a small village called Kosorzha, Melnik came of age during the Russian Revolution's aftermath. After the Civil War, his family moved to Kharkiv—then the capital of Soviet Ukraine—where his father found work in publishing. Young Timofej took his first steps into photography not with a camera, but in the darkroom. He trained as a photo lab technician for the Communist Party newspaper Kommunist before being trusted with the camera itself. From apprentice to full correspondent, his rise was swift—by the late 1930s, he was already exhibiting award-winning photographs in Moscow.

Then came war. When the Nazis launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Melnik was stationed with the Baltic Military District newspaper For the Homeland in Riga. As the front collapsed, the editorial team fled east. Along the way, Melnik developed a rhythm: photograph, develop, print—in bunkers, in trucks, wherever he could. His subjects were often posed, ideologically safe—heroes, ceremonies, victories.

He was wounded in 1942 near Staraya Russa—shrapnel lodged close to his heart. He survived, barely. Two months later, he was back photographing—this time for the 11th Army's Banner of the Soviets, and then for the Air Force's official organ, Stalin's Falcon. That assignment offered him better equipment, more artistic latitude—and a broader canvas: from the skies over Kursk to the burning ruins of Königsberg.

But it's Berlin that crowns Melnik's legacy.

In those final days of April and May 1945, Melnik followed Soviet troops street by street. His images capture more than tanks rolling toward the Reichstag or German prisoners in long columns. They show exhausted faces, soldiers embracing beside the Victory Column, spontaneous concerts among rubble. He captured the Stunde Null, Europe's zero hour—its violence, its surreal calm, and its aching relief.

At midnight on May 8, 1945, Melnik stood among those summoned to Berlin-Karlshorst. In a room filled with uniforms, reporters, cameramen, and photographers, he witnessed the act that ended the war in Europe. The German Wehrmacht surrendered unconditionally. Together with fellow Soviet photographer Iwan Schagin, he documented every gesture of that evening. These photos now form the most prominent part of the Berlin Museum Karlshorst—so numerous that only 50% have been digitized so far. You can browse some of them here:

THE GERMAN SURRENDER IN MAY 1945, Museum Berlin Karlshorst

Four days earlier, he had captured the Soviet 5th Shock Army parading in the Lustgarten. That photo—Soviet soldiers standing proud beneath the colonnades of a broken Berlin—was printed in the Red Star. You can see the photo here:

Eine Kriegsfotografie von Timofej Melnik, 2021, Margot Blank

Melnik kept working after the war. He became chief photo editor for the Soviet Aviation paper, later joining Red Star, and eventually Pravda. His war wounds caught up with him, but not before decades of chronicling Soviet life—its idealism, its illusions, its steel-bound pride. He died in 1985, in a country already beginning to shift beneath his feet.

Ivan Šagin: from Moscow to Berlin and back.

The third and final photographer in this journey is Ivan Šagin.

One of his most striking images shows Nazi vehicles abandoned in the snow near Moscow. The date is December 5th, 1941 — the day the Soviet counteroffensive began. The tide was turning. And Shagin was there, with his camera.

From that moment, he followed the Red Army all the way to Berlin. His lens traced the full arc of the war, from the defensive trenches outside Moscow, across the Ukrainian plains along the Dnieper, through the smoldering ruins of liberated cities, and finally into the heart of the Reich. His photos document the road to victory, step by step — a silent, visual diary of destruction and resistance.

Many of his wartime photographs are now preserved at the Museum Berlin-Karlshorst, where they stand as a powerful counterpoint to the propaganda and silence of those who lost.

BROWSE PHOTOS: MUSEUM DIGITAL DE

Shagin was born in 1904, the son of a poor peasant in a village near Moscow. He lost his father early, worked as a sailor on the Volga, then moved to the capital in search of a future. Photography was his escape — first a hobby, then a calling.

In the 1930s, he became one of the most respected photojournalists in the Soviet Union. His style was direct, often frontal, but full of life and movement. He loved diagonal compositions and close-ups, capturing both the vastness of history and the intimacy of individual faces.

During the war, he photographed nearly every major battle. He was there at the Elbe, when Soviet and American soldiers shook hands. He was there in Berlin, at the gates of the Reichstag. He documented the difficult lives of the wounded, civilians, and refugees, while maintaining a respectful distance.

Shagin lived until 1982, long enough to see his work recognized as part of the Soviet visual canon. His images remain among the most powerful ever taken of the Second World War.

Frames of truth.

Whether Western or Soviet, all World War II photographers were embedded. Each arrived at the front with their own background, convictions, and loyalties. Yet the images they left us speak a truth that transcends staging—even when retouched, reframed, or reproduced.

Today, in an age where the line between real and fake blurs by the hour—where every image feels staged, and propaganda, now rebranded as disinformation, thrives on this confusion—these photographs remain vital. They show us destruction and death, courage and revenge. They show us the scrawled boasts and broken dreams left behind on the walls of a fallen Berlin.

Walking through quiet galleries and unexpected venues of the underground Berlin, I didn’t just look at the photos. I watched the viewers too. No need for psychic powers: you could see it in their eyes. Each one paused, caught in a moment of reflection.

Because photography still holds that power—when it’s not trapped in a feed, but printed, framed, and hung on a wall. A wall that might still bear the scars of the past.

Born as Iosif Solomonovich Grossman, from a Jewish family in Ukraine. Author, among others, of Life and Fate (1959).

https://www.rferl.org/a/the-great-russian-photographer-who-was-a-chronicler-and-victim-of-history/28366539.html

Nice post and great to have the links embedded for more images and information. Thx.