Roses for Clara Zetkin.

8 March may seem like a worn out, empty and inconclusive holiday. But its roots are revolutionary, and they can still be found here in Germany.

Feminism is not dead, as some say. But it is certainly not doing well in 2024. The ground our foremothers fought so hard for is under siege.

Authoritarian regimes are waging a brutal war against women's autonomy. A distorted definition of diversity has led our 'immigration societies' to tolerate lifestyles that suppress women's freedom. Femicide continues to rise everywhere. Our far right (the German AFD is a blatant example, even though its co-leader is a woman) is proposing a vision that sets women back decades.

But perhaps most disappointing is the division within feminism itself. Women are turning on each other, putting ideology before sisterhood. The silence surrounding Israeli women since 7 October, their suffering erased or ignored. From the silenced Israeli voices in European and North American squares to the online spaces where violence against women is a selective outrage, the cracks are undeniable.

It's enough to make you wonder: is International Women's Day a relic of a bygone era, or is it more relevant than ever?

For me, 8 March has never been a celebration. I always felt distanced from it. Then I came to Berlin.

Back to the roots. The socialist story of 8 March.

In Berlin, 8 March has been a public holiday since 2019. Together with Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, they are the only two Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany to celebrate it as a holiday.

There are 27 other countries in the world where 8 March is a public holiday: almost all of them are former Soviet or former socialist countries. It is notably absent from most other Countries´ calendars, or has been reduced to its minimal, irrelevant, celebratory terms.

Why is that? Because 8 March is not, as is often thought, a child of the bourgeois suffragette movement. It's a fiery offspring of revolutionary socialism. It was the brainchild of a remarkable German woman: Clara Zetkin, a feminist, pacifist and socialist firebrand.

Clara Zetkin dominated the landscape of former GDR/DDR cities. Streets, parks and statues in every town and city spoke her name. But the post-reunification 90s brought a wave of "cancel culture". Clara-Zetkin-Strasse in Berlin? Renamed back to "Dorotheenstrasse" to reflect the old Reich. Yet, popular resistance grew. People realised the power of her legacy, especially for women's rights.

Today we can pay tribute to her statue in East Berlin, visit a museum in Brandenburg or take a walk in the Clara Zetkin Park in Leipzig. Some do this on 8 March. Some take flowers to the statue of Clara on that day, remembering the true roots of Women's Day.

Clara Zetkin´s call for an international day of marching.

On 26 August 1910, over 100 delegates from 17 nations gathered in Copenhagen for the Second International Conference of Socialist Women.

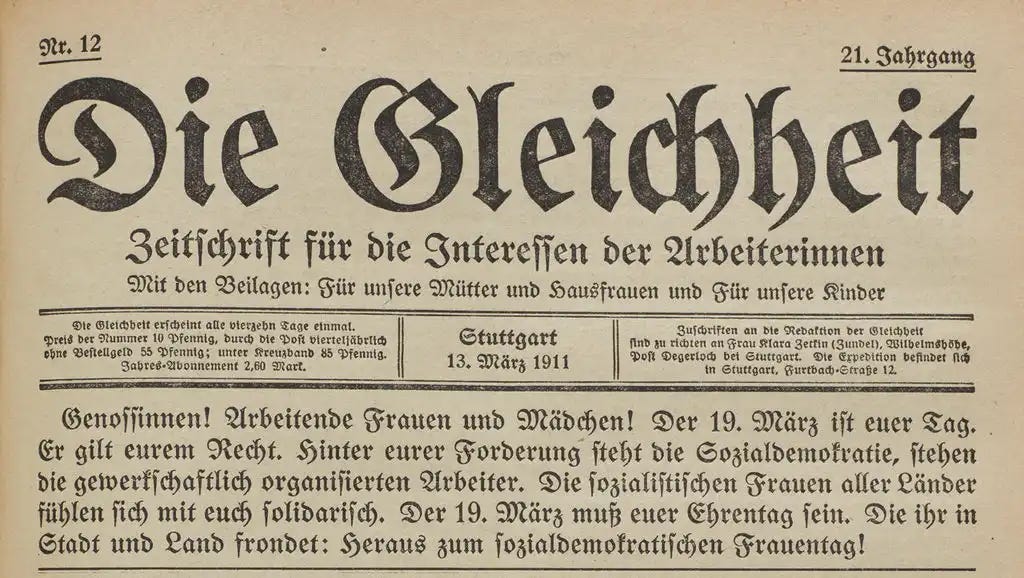

Clara Zetkin, who was chief editor of the Stuttgart magazine "Die Gleichheit" (The equality) and chairwoman of the Women's International Council of Socialist and Labour Organisations, led the twelve people of the German delegation: among them, her good friend Rosa Luxemburg.

While social issues and political turmoil were addressed, the most heated debates centered on women's suffrage. English delegates favored collaboration with existing "bourgeois" feminist movements, the "leftists" championed integrating the fight for universal suffrage into the broader working class struggle. While the British were ready to settle for “women's suffrage" only for unmarried women with property, the socialist did not accept a compromise: it was due to be universal suffrage, nothing less.

And, the socialist women sought far more than just voting rights. They envisioned protections for working women, childcare support, and equal treatment for single mothers. For Clara Zetkin and the German socialists, the women's movement was a thread woven into the larger tapestry of the class struggle.

Inspired by the American Women's Day of 1909, Clara Zetkin and the Trade Unionist Käte Duncker proposed an annual International Women's Day with a focus on universal suffrage. Their motion passed:

»Im Einvernehmen mit den klassenbewussten politischen und gewerkschaftlichen Organisationen des Proletariats in ihrem Lande veranstalten die sozialistischen Frauen aller Länder jedes Jahr einen Frauentag, der in erster Linie der Agitation für das Frauenwahlrecht dient. Die Forderung muss in ihrem Zusammenhang mit der ganzen Frauenfrage der sozialistischen Auffassung gemäß beleuchtet werden. Der Frauentag muss einen internationalen Charakter tragen und ist sorgfältig vorzubereiten.«

"In agreement with the class-conscious political and trade-union organisations of the proletariat in their country, the socialist women of all countries organise an annual Women's Day, the main purpose of which is to agitate for women's suffrage. This demand must be considered in the context of the whole women's question according to the socialist conception. Women's Day must have an international character and be carefully prepared".

(Source: Renate Wurms: "We want freedom, peace and justice. The International Women's Day. On the history of 8 March. March", 1980)

On 13 March 1911, "Die Gleichheit" published Clara Zetkin's passionate appeal for participation in the first International Women's Day: "Comrades! Working women and girls! March 19 is your day. It is your day for your rights".

Her message resonated: over a million people across Germany, Austria, Denmark and Switzerland took to the streets, with 30,000 women marching in Berlin alone.

The chosen date, March 19th, was a deliberate echo of the "March Martyrs" – a day of bloodshed in 1848 when German Reich citizens demanded democratic rights and 250 people died that day, yet paving the way for the first democratic elections in Germany - although only for the male population. (See also “Demokratie – Eine deutsche Affäre”, "Democracy - A German Affair”, Hedwig Richter, 2020).

Who was Clara Zetkin?

Born Clara Eißner in 1857, Zetkin's path was shaped by both parents: a bourgeois women's rights activist mother and a teacher-cantor father inspired by the ideals of the 1848 revolution. Her parents enabled her to study modern languages in Leipzig.

There she became interested in socialist ideas and joined the Socialist Labour Party of Germany in 1878. This was a time of intense class consciousness and revolutionary fervor in Germany, fueled by rapid industrial development.

At the age of 21, Clara met and fell in love with the Russian Jewish socialist Ossip Zetkin. After the German Empire expelled Ossip as a "troublesome foreigner", they fled first to Zurich and later to Paris. There the Zetkins had two sons: she worked hard to support the family, but also actively engaged with politically like-minded people. Despite shyness, Zetkin emerged as a powerful speaker, agitator, and organizer at the 1889 Paris International Labour Congress.

After Ossip's death in the same year, Zetkin returned to Germany, settling in Stuttgart, a German State where women could participate politically. Taking over "Die Gleichheit" in 1891 as editor-in-chief , she transformed it into Germany's leading women's publication, reaching 125,000 readers by 1914.

A workaholic and gifted public speaker, she delivered over 260 speeches annually. Beyond grand stages, she preferred smaller groups, offering education and practical help through clandestine "workers' education courses."

Zetkin's radical vision: women won't be free until capitalism falls.

The ardent socialist Clara Zetkin wasn't satisfied with the formal-legal wish-list of bourgeois feminism. Legal equality on paper? A deception. As she said:

“Mag man heute unsere gesamte Gesetzgebung dahin abändern, dass das weibliche Geschlecht rechtlich auf gleichen Fuß mit dem männlichen gestellt wird, so bleibt nichtsdestoweniger für die große Masse der Frauen die gesellschaftliche Versklavung in höchster Form weiter bestehen: ihre wirtschaftliche Abhängigkeit von ihren Ausbeutern.”

“Today, our entire legislation may be changed so that the female sex is legally placed on an equal footing with the male sex, but for the great mass of women, social slavery in its highest form remains: their economic dependence on their exploiters.”

Forget incremental reforms. For Clara Zetkin, true women's liberation, like freedom for all, was locked in the fight against capitalism. Only in a socialist society, she argued, could women, like labourers, attain full possession of their rights:

"Ihre soziale Befreiung erringt sie, die Proletarierin, nicht wie die bürgerliche Frau und zusammen mit ihr im Kampf gegen den Mann ihrer Klasse, sie erobert sie vielmehr zusammen mit den Mann ihrer Klasse im Kampf gegen die so genannte bürgerliche Gesellschaft."

"She, the proletarian woman, does not win her social liberation like the bourgeois woman and together with her in the struggle against the man of her class, she rather conquers it together with the man of her class in the struggle against so-called bourgeois society."

Revolution First, Equality Later: In Zetkin's eyes, women's rights were a consequence, not a cause, of a socialist revolution. Pushing for equality within the existing system was like "window-dressing" – treating symptoms, not the disease, which was private property under capitalism.

Love, war, revolution.

Zetkin met her second husband Friedrich Zundel, 21, during a student strike when she was 39. He had just been expelled from university as an art student. Their Stuttgart home became a left-wing celebrity hotspot, hosting even Lenin. Zetkin forged a deep bond with Rosa Luxemburg.

When Germany declared war in 1914, Zetkin's world collapsed. Arrested for 'attempted treason', the 58-year-old endured three months in prison, illness and socio-political isolation.

The Russian October Revolution of 1917 revived hope for the politically homeless Zetkin after the SPD's reformist turn. She saw it as a forerunner of equality and emancipation.

Zetkin became a communist, joined the Spartacist League and in 1919 became a founding member of the KPD, which she represented in the Reichstag until 1932. She also joined the Executive Committee of the Comintern.

But the male-dominated Weimar KPD made the independent-minded Zetkin uncomfortable. She criticised ideological diktats as the Stalinist terror loomed, and by the late 1920s the grand dame of the German left was marginalised. She was at odds with her party and the Comintern.

Zetkin worried early on about the rise of fascism. Her calls for a united left front against the strengthening NSDAP fell on deaf ears. Despite the antipathy towards Stalin, she retired to Moscow, tired and ill.

Yet she remained a disciplined party soldier. With the last of her strength and accompanied by her son, she took a train from Moscow to Berlin to open the last legislative period of the German Reichstag as its oldest former president. She announced her decision to come to Berlin to do her duty with these words:

“Ich werde kommen – tot oder lebendig.”

"I will come - dead or alive."

Her opening speech to the Reichstag (30. August 1932, herein in the full recording), delivered in a tired voice but with a passionate, desperate stance, was a call for action against fascism and for the unification of left democratic forces:

“The struggle of the working masses against the oppressive hardships of the present is at the same time the struggle for their complete liberation. It is a struggle against enslaving and exploiting capitalism and for redeeming, liberating socialism. The gaze of the masses must be kept fixed on this shining goal, not clouded by illusions in liberal democracy and not deterred by the brutal forces of capitalism, which seeks its salvation through new world massacres and fascist civil war murders. The call of the hour is for the united front of all working people to repulse fascism, to preserve the strength and power of their organisations for the enslaved and exploited, and even for their physical lives.”

“Der Kampf der werktätigen Massen gegen die zerfleischenden Nöte der Gegenwart ist zugleich der Kampf für ihre volle Befreiung. Er ist ein Kampf gegen den versklavenden und ausbeutenden Kapitalismus und für den erlösenden, den befreienden Sozialismus. Diesem leuchtenden Ziel muß der Blick der Massen unverrückt zugewandt sein, nicht umnebelt durch Illusionen über die befreiende Demokratie und nicht zurückgeschreckt durch die brutalen Gewalten des Kapitalismus, der seine Rettung durch neues Weltvölkergemetzel und faschistische Bürgerkriegsmorde erstrebt. Das Gebot der Stunde ist die Einheitsfront aller Werktätigen, um den Faschismus zurückzuwerfen, um damit den Versklavten und Ausgebeuteten die Kraft und die Macht ihrer Organisationen zu erhalten, ja sogar ihr physisches Leben.”

The final, utopian words of the speech were these:

“Ich eröffne den Reichstag in Erfüllung meiner Pflicht als Alterspräsidentin und in der Hoffnung, trotz meiner jetzigen Invalidität das Glück zu erleben, als Alterspräsidentin den ersten Rätekongress Sowjetdeutschlands zu eröffnen.”

"I am opening the Reichstag in fulfilment of my duty as President in my old age and in the hope that, despite my present invalidity, I will be fortunate enough to open the first Congress of a Soviet Germany as President in my old age."

Zetkin witnessed the Nazi seizure of power between January and March 1933. On 20 June 1933, she died in Archangelskoye, Russia, and was buried next to the Kremlin wall. 400,000 people came to bid her farewell; Joseph Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov carried her coffin.

Ich will dort kämpfen, wo das Leben ist.

Clara Zetkin,

5.7.1857 - 20.6.1933

Other women received flowers in Berlin on 8 March. Here is Kathe Köllwitz (1867-1945), the pioneering artist who captured the suffering, strength and resilience of working-class women in Germany before and after the First World War. Her prints, lithographs and sculptures brought social issues and injustices from the forgotten corners of the city to the main stage of art. Another story worth knowing.

Interesting post. Thank you. I was in Berlin recently for the Half Marathon and visited Marzahn to see the Womacka murals. I’ll have to return to visit Clara’s statue next time.