"I'm here to show: I'm still alive, I'm still here."

May 15, 2024, marked the 80th anniversary of the extermination of Hungarian Jews. Sharing this history not only reminds us of Europe's past but also celebrates those who survived and chose to stay.

Ten days ago, Auschwitz-Birkenau commemorated Holocaust Remembrance Day with the 36th March of the Living. This year's event was different. It was not only marked by the 7 October massacre.

Eighty Hungarian Holocaust survivors, joined by hundreds of Hungarian students, started the march from the Dohany Synagogue in Budapest the day before, on 5 May. They arrived at Keleti railway station, the site of the first deportation of Jews from Budapest to Auschwitz-Birkenau. From there they embarked on a train journey that retraced the death transports from Hungary to Oświęcim in southern Poland, the town near the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. They then joined the international march.

15 May 2024 marked 80 years since the Hungarian Jews got exterminated during the Holocaust. From that date until 9 July 1944, Hungarian gendarmerie officers, led by German SS officers, deported some 440,000 Jews from Hungary. They were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where most of them were killed in the gas chambers immediately after arrival and selection.

The deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau was the only operation fully documented by photographs among the 1500 transports that arrived from all over Eastern Europe. On 26 May 1944, a train carrying some 3,500 Jews deported from northern Hungary arrived at the camp gates. Two SS men photographed the people as they disembarked and lined up for selection. These images have become iconic, appearing in documentaries, films, exhibitions and textbooks.

Although the deportation of Hungarian Jews took place towards the end of the war, when Germany was no longer able to maintain fully functioning logistics in the occupied territories, it was so to say the most efficient.

Adolf Eichmann was the mastermind behind the 151 daily transports of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz between 15 May and 9 July 1944. He arrived in the country shortly after its occupation in March and was given the task of organising the liquidation. In less than two months, some 440,000 Jews from Hungary were deported to the camps. Almost all of them were gassed on the spot.

Hungarian Jews: from the Golden Age of Mitteleuropa to Annihilation.

On May 15, 1944, a significant chapter in European Jewish history began to close.

Hungary, once home to the second-largest Jewish population on the continent, boasted nearly a million Jewish residents on the eve of World War I. The vibrant city of Budapest, in particular, had a population that was 25% Jewish at the start of the 20th century.

At that time, Hungary was much larger than its present-day borders, constituting half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and encompassing territories now part of Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Ukraine, and Austria.

The rich and diverse Jewish culture was a result of more migration waves from Central and Eastern Europe, including immigrants from Germany, the Austrian domains, and the Russian Empire.

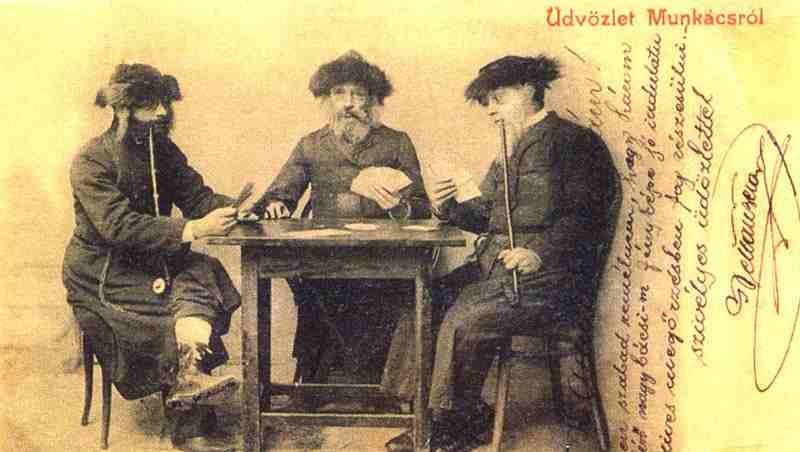

Because of the variety of origins of the Jewish population in Hungary, Jewish life and experience were far from uniform throughout the country. While Budapest boasted a sophisticated and integrated Jewish community that had adopted Hungarian customs, there were stark contrasts with the modest lifestyles of Hasidic Jews living as farmers and lumberjacks in rural villages scattered across the Carpathian Mountains.

But Hungary's cultural diversity is part of its allure, with its varied roots, customs, and languages. This contrasts with the myth of a purely Magyar country, a notion often politically exalted today but not reflective of its history.

The Italian-Mitteleuropean author Claudio Magris once described Budapest as "the most beautiful city on the Danube."1 I could not agree more: compared to Vienna, Budapest is more monumental, more colorful, and its heart is the Danube itself, unlike Vienna where only a secondary canal crosses its center. The Danube in Budapest provides a magnificent backdrop for palaces and fortresses.

Just a 20-minute walk from the Széchenyi Chain Bridge, the most famous bridge over the Danube that connects Buda and Pest, lies the city's Jewish quarter. Its most renowned building is the synagogue on Dohány Street.

This synagogue is the largest in Europe and the second-largest in the world. It belongs to the Neolog Jews, a uniquely Hungarian branch of Judaism that sought to modernize the religion and integrate into Hungarian society.

Modernisation gained momentum from 1867, when Hungary reached a historic compromise with Austria and gained semi-independent status within the newly formed Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Jews were also unconditionally emancipated in 1868, gaining almost the same rights as Magyars. They could attend universities, serve in the army and enter politics.

Within a few years, Budapest's Jews had come to occupy a central position in the country's economic and cultural life. Many Jews adopted Magyarisation, abandoning their native languages, such as Yiddish, in favour of Hungarian. The period between 1867 and 1914 was the golden age of Jews in Hungary and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Anti-Semitism on the rise: 1880-1940.

The wave of anti-Semitism that spread across Europe in the late 19th century was largely driven by rebellion against urban capitalism and the onset of globalization, with Jews perceived to be the primary beneficiaries.

Jewish prominence in law and medicine at the University of Budapest led students to protest against their overrepresentation in 1881. By 1900, Jews were the most educated group in Hungary, making up 50% of all medical students and a third of the law faculty. The years 1881-1882 saw a wave of anti-Jewish riots and pogroms throughout south-western Imperial Russia, now modern-day Ukraine and Poland.

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Hungarian Jews enthusiastically supported the Austrian Empire's war against the anti-Semitic Russian Empire. They served in the joint Austro-Hungarian army. However, their patriotism did not protect them from the consequences of the dissolution of the dual monarchy in 1918.

The newly formed Hungarian Republic, significantly reduced in both population and territory, experienced instability similar to that of Germany. It was plagued by inflation, civil war and the threat of Bolshevism. Jews became convenient scapegoats.

In 1920, Hungary became the first European country to introduce an anti-Jewish law: the numerus clausus, which limited the number of Jewish students admitted to universities. In the early 1930s, the new Hungarian government embraced National Socialism and began cooperating with Germany in the hope of regaining lost territories. New laws were introduced later to limit the role of Jews in the Hungarian economy and professions.

It's important to remember this background, because in the last two decades there have been attempts to rewrite history and place the blame for anti-Jewish sentiment and legislation, culminating in the Holocaust, solely on Germany. Hungary played a part in these events from the very beginning.

The Second World War and the extermination of Hungarian Jewry.

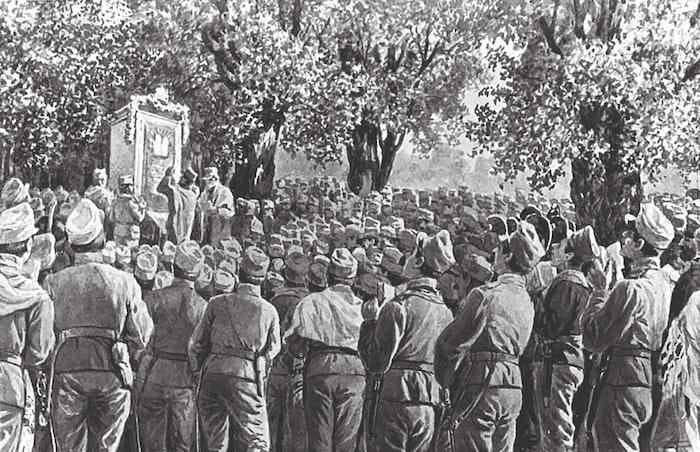

In 1941, Hungary contributed 90,000 men to Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union. These troops served mainly in Ukraine and parts of present-day Belarus, suffering heavy losses due to lack of equipment and motivation. In 1942, however, Hitler demanded more troops. This led to the deployment of an additional 200,000 Hungarian soldiers, including between 32,000 and 39,000 Jewish forced labourers, who were directed towards the Don River.

As the Germans advanced towards Belgorod, a 700km gap opened up in what is now Ukraine. It was the responsibility of Germany's allies, the Hungarians, the Romanians and the Italians, to hold this gap. My grandfather, an infantry captain, was among the Italians, and I am proud to say that he managed not to commit any atrocities at a time when many were committing terrible acts.

As the Eastern Front began to collapse with Germany's failure to capture Stalingrad (1942-1943), the Hungarian government attempted to break away from its alliance with Germany and negotiate a separate peace with the Allies, much like Italy after the end of Mussolini's regime. This led to Hitler's decision to occupy Hungary.

A small German military force was sent into Hungary on 19 March 1944. It took them about a month to spread out across the country and take full control. A few days later, SS Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Adolf Eichmann arrived in Hungary with 150 SS men with the mission of eliminating the Jews of Hungary as quickly as possible.

Many Hungarians today, influenced by internal propaganda, will try to deny any involvement in the liquidation of the Jews. However, this is not true: the cooperation of a significant number of Hungarians and Hungarian institutions was crucial in gaining control of all Jewish communities within a few weeks in April 1944. These people were sent to cities used as collection centres. Hungarian gendarmes were sent to the countryside to round up Jews of all ages and send them to the cities. The Jews were forced into closed urban areas known as ghettos. This task was carried out efficiently and with conviction by Hungarian officials and policemen, not Germans.

Back to where we started: 15 May 1944 - 13 February 1945.

The transports began on 15 May 1944. The transports were stopped on 8 July, under pressure from the Allies and the Pope, after reports emerged about the fate of the Jews at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

By the end of July 1944, the only remaining Jewish community in Hungary was in Budapest. The July halt was merely a pause. In October 1944, a new Hungarian government controlled by Nazi Germany resumed the persecution of the Jews.

From October 1944 to early January 1945, thousands of Jews were taken to the banks of the Danube and shot. An impressive memorial on the banks of the Danube in Budapest commemorates these murders: 60 pairs of metal shoes represent the people tied together and shot. Only every other person was shot; the others drowned, dragged down by the dead and dying.

Shortly afterwards, at least 50,000 Jews were rounded up and sent to build fortifications on the Hungarian-Austrian border. This new form of deportation, which began on 8 November and continued until early December, is known as the Hungarian Death March.

Meanwhile, the Red Army arrived in Hungary and began the siege of Budapest on Christmas Eve 1944. The siege lasted 1 month, 2 weeks and 6 days until they captured the city on 13 February 1945.

Yesterday, today.

The political use of memory by populists in Europe, including Hungary, has become commonplace. Such manipulation underlines the importance of understanding history and critically analysing the narratives presented to us. The argument that the Holocaust of Hungary in 1944 was solely the result of Nazi actions is similar to the narrative presented in Poland.

In Hungary, the preamble of the Constitution was rewritten in 2011-2012 to state:

“We refuse to recognize the suspension of our historical Constitution that occurred on the strength of foreign occupation. We do not accept any statutory limitation of the inhuman crimes committed against the Hungarian nation and its citizens under the national socialist and communist dictatorship.”

The Orbán government's official interpretation has been part of the Hungarian constitution since 1 January 2012. The preamble refers to the "state self-determination of our homeland that was lost on the nineteenth of March 1944", implying that Hungary and the Hungarian people bear no responsibility for events post this date until 1990.

Viktor Orban has shown some ambiguity over time. He is formally a friend of Israel and has made significant but unclear statements. During the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Hungarian Holocaust in 2014, he acknowledged Hungarian complicity: "We were without love and indecisive when we should have helped," and during his visit to Israel in 2017, he admitted that the Hungarian government failed to protect its Jewish citizens during World War II.

Nevertheless, Orban has also been involved in anti-European propaganda, using anti-Semitic imagery to target George Soros and his son. The most recent incident, in November 2023, involved posters featuring Ursual van der Leyen and Alex Soros, George Soros' son.

Despite these contradictions, Hungary remains a safe haven for its Jewish community. With a population of around 75.000 to 100,000, Hungary ranks among the top 15 countries in the world in terms of Jewish population. Public expression of Jewish faith is unproblematic, anti-Israel protests at universities are non-existent, and desecration of monuments is rare, despite a significant neo-Nazi presence.

The future of this peace remains uncertain, but as Holocaust survivor Dr. Peter Köves put it during the March of the Living:

"I'm here to show: I'm still alive, I'm still here."

Dive deeper

History of Hungarian Jews

(English) History of Jewish Hungary from the Middle Ages to 1918, Yivo

(German) Judentum in Ungarn, German-Hungarian Institute, 2020

Deportation and killing

(English) From Golden Age to Destruction, Science Po, Paris, 2015

(German) 🎧 Die Quelle sprechen, Speak the source, 15 episodes (Document readings and testimonies), Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin, 2023

Jews in the Austrian-Hungarian army

(English) Habsburg Sons: Jews in the Austro-Hungarian Army, 1788–1918 (book)

(German) Weltuntergang und Fronteinsatz (End of the world and frontline operations), Deutschlandfunk.de

I continue to be delighted with the quality and eloquence of journalism on Substack, including of course 'Beyond Berlin'. Thank you again for a great article on an important topic. You deserve wider recognition.