Charkiw, Tbilisi: how far does Europe really stretch?

The images from Kharkiv and Tbilisi challenge us as Europeans. How we respond could determine not only the fate of these countries, but also the raison d'être of the European project.

Three weeks between Kharkiv and Tbilisi.

On the afternoon of Saturday 25 May, two guided bombs hit a building materials hypermarket in the suburbs of Kharkiv, killing 16 people and wounding over 40, while more than 200 were inside the store.

Kharkiv, Ukraine's second largest city with a population of nearly 1.4 million - about the size of Milan - is a major economic centre. It's home to one of Ukraine's most prestigious universities, the second oldest in modern Ukraine. Russia launched an offensive on Kharkiv, which has been halted. In response, the Russian army has adopted a simple strategy: bomb, bomb, bomb - mostly civilian targets.

Meanwhile, thousands of Georgians have been taking to the streets of Tbilisi for weeks to protest against the new law 'On Transparency of Foreign Influence'. The law targets NGOs and media outlets that receive more than 20% of their annual income from foreign sources. It requires them to register as organisations serving foreign interests. Internationally, the law is commonly referred to as 'Russian Law 2.0' due to its similarities to Russia's 2012 law on foreign agents, which has been instrumental in consolidating Putin's power.

From the outside, you might think that we Europeans would be deeply impressed by the sea of blue EU flags and the rendition of Beethoven's Ode to Joy, the Union's anthem, in Tbilisi's main square. And moved by the Ukrainian images that clearly and unequivocally document a genocidal war in action.

But the truth is less romantic: the protests arouse some sympathy, but also concern. Some wonder: "Will there be another war? Will there be more unrest and refugees?" And some ask, "Georgia is in the Caucasus, but is that still Europe?" and "An XXL Europe that includes Ukraine, does it really make sense?

An even bigger Europe to the east: why?

Legitimate questions and concerns, and impossible to address in a blog post. But the last two years have reminded us that narrative is powerful.

Ukraine is a case in point. Vladimir Putin started with the notion that everything the Russian Empire claimed two centuries ago, and what the Soviet Union subsequently retained, was inherently "Russian". He then used pseudo-historiography to argue that Ukraine and Russia are identical, going back to a time before the Moscow Principality even existed.

On our side, what narrative can we offer in response?

It would be easier to answer this question if we had used the past twenty years, since the significant enlargement to the East in 2004, to write a common history of Europe, one that includes both the West and the East.

It would be easier to answer, if we spent time discussing not only how Europe should work, but also what it stands for.

Given the number of democratic setbacks we've seen over the last fifteen years, particularly in the countries of the 'new Europe', it is appropriate to question the boundaries of this Europe.

If a question is not easy to answer, change the question.

What makes Ukrainians and Georgians feel European? What motivated them to risk their lives waving the European flag on Maidan Square in 2014, and even earlier in Georgia in 2008? Was it the thrill of taking part in the complex five-year European budgetary procedures? The desire to vote for a huge and somewhat invisible parliament, shuttling between Strasbourg and Brussels? A thirst for EU money? Collective sentiment is never born of short-term interests. It is rooted in distant memories, often full of myths.

So today, let me turn the question from a west-to-east perspective - how far can Europe go? - to an East-West perspective.

Where does Europe come from? How much of Europe's history depends on what happened there?

Leave today's news and travel with me back in time to explore this question through the lens of history, archaeology and myth.

1. From the Black Sea to the Black Lands: Europe's breadbasket.

The history of Europe might have been different if the global sea level had not risen after the last Ice Age, allowing Mediterranean waters to flow into the Black Sea basin via the Turkish Straits some 9,000-8,000 years ago.

The water flew and the sailors came.

They crossed the Turkish Straits and entered the Black Sea. Its darker colour compared to shallower seas such as the Mediterranean led to its name 'Black Sea'. However, this name has evolved over time, reflecting changing perceptions and attitudes towards the region. Initially, during their explorations, the Greeks called it "Pontos Axeinos" (Πόντος Ἄξεινος), implying an "inhospitable" or "hostile" sea.

Interestingly, the very darkness that made the sea seem inhospitable also made the lands on its northern shores highly desirable.

These areas, commonly referred to as "Black Lands" or "Black Soils", correspond to the Ukrainian plains. The black colour of the soil, rich in humus and darkened by phosphorus and ammonia compounds, gives it a distinctive dark and fertile character.

Historically, these lands have been the breadbasket of Europe, making them highly sought after for longer than one might think.

2. Ukraine: Europe's (and the world's) first cities.

It comes as a surprise to many that the oldest known human cities are in what is now Ukraine, preceding even the cities of Babylon.

These early agro-pastoral communities introduced domesticated plants and animals to the fertile forest-steppe zone between 6,100 and 5,400 years ago. They also developed 'megasites': extensive but low-density urban settlements, with over 3,000 houses, larger than the first Mesopotamian cities.

Unlike Mesopotamia, these ancient Ukrainian settlements had no central financial, religious or political authority. Built in several concentric circles of houses separated by large open spaces, these settlements belonged to remarkably egalitarian communities. There were no signs of material or social differentiation: all houses were similar in size or materials, and there were no prestige goods.

These communities were modest and left a minimal ecological footprint. Unused wooden houses were burnt down, allowing the area to recover over time. Today, they could be a perfect fit for the European Green Deal.

3. From here, the Proto-Indo-European language family spread throughout Europe.

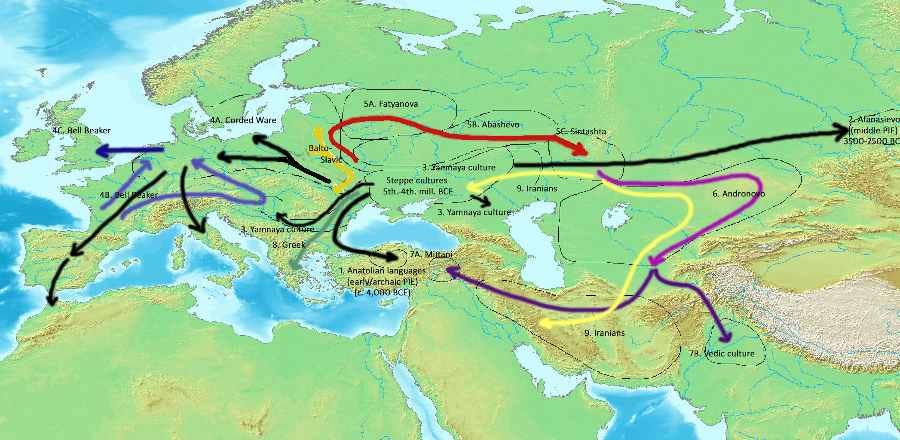

The vast majority of Europeans speak Indo-European languages. These languages originated - surprise! - in the Pontic-Caspian steppe around the Black Sea, covering parts of modern Ukraine and southern Russia. In this region, the Yamna culture (c. 3600-2300 BC) is considered the source of the earliest Indo-European languages and peoples.

The major technological advance enabling these people to spread across Asia and Europe was the domestication of horses and the introduction of wheeled vehicles.

Between about 3300-2500 BC, they migrated westwards into Europe, bringing with them ancestral lineages that developed into Indo-European language families such as Italic, Celtic, Germanic and Balto-Slavic. The Yamna also spread across Asia, contributing to the spread of Indo-Iranian languages like the precursors of Sanskrit.

4. From "inhospitable" to "hospitable sea": the Greeks colonise the Black Sea.

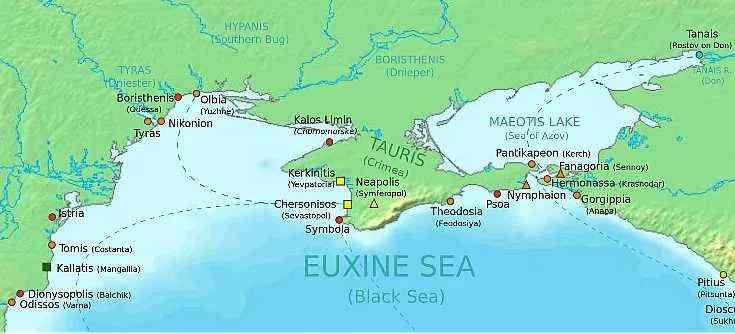

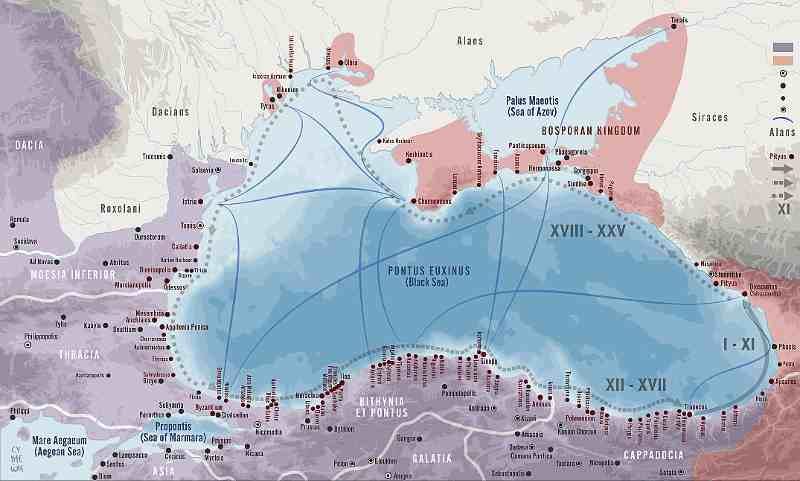

When the Greeks began to colonise the north of the Black Sea coast from the 6th century BC, they discovered that it was not as inhospitable as they had previously thought. So, they euphemistically changed its name from Pontos Axeinos to 'Pontos Euxeinos' (Πόντος Εὔξεινος), the 'hospitable sea'.

At this time, the Greeks were not a unified nation, but rather a collection of independent city-states, including famous ones like Athens, Sparta, Mycenae and Miletus. Each of them established their own colonies along the Baltic coasts.

If you explore Google Maps, particularly in Crimea, you'll encounter several city names reminiscent of Greek, such as Sevastopol. None of these names correspond 1:1 to old Greek colonies: they were given under the German-Russian Empress Catherine II as a tribute to ancient history, with the intention was to create a perceived continuity between the Greek domains and the Russian Empire - a prime example of historical manipulation.

What about the actual Greek colonies?

Olbia was one of the most significant: Established in the 7th century BC near the future port of Odessa, it served as a crucial trading hub for grain destined for Athens and other Greek cities, prefiguring Odessa's role. Panticapaeum, another important center, was established by Miletus in the 6th century BC. Today, it is known as Kerch, the location of the infamous Russian bridge that links Crimea to the Russian mainland and secures control of the Sea of Azov. Chersonesus was established in the 5th century BC in southwestern Crimea, near today's Sevastopol. It was renowned for its vineyards and wine exports.

These Greek colonies were not basecamps for the occupation of internal territories. Instead, they served as commercial hubs for import-export trade. For Greeks, the main trading partners were the Scythians.

5. Greeks and Scythians: symbiosis and myths.

The Scythians were an ancient Iranian-speaking nomadic people who populated the steppes of modern Ukraine and southern Russia between the 7th and 3rd centuries BC. Illiterate, their legacy is largely preserved through exquisite golden artefacts found in the tombs of warriors. Our knowledge of them comes mainly from the writings of the 5th century BC Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus, de facto the first known historian of Ukraine.

The relationship between the Greek settlers and the Scythians began as a commercial one: Athens' power among the Mediterranean city-states would not have been possible without Ukrainian grain.

It soon developed into ethnic and cultural ties, with some Scythians intermarrying with Greek settlers and living together in multicultural, multilingual trading communities along the Dnipro River and the Black Sea coast.

This fusion gave shape to new traditions and some of the most famous Greek legends, which have influenced European literature, art and theatre for centuries.

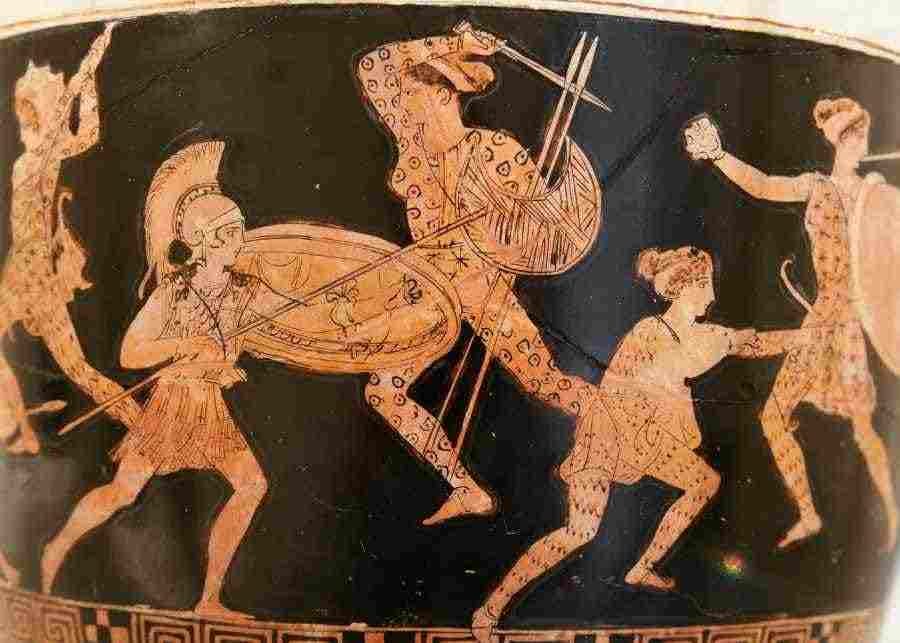

The Amazons, those famous warrior women, were no mere myth. They made their historical debut through Herodotus in the 5th century BC. According to Herodotus, they invaded Scythia, impressed the Scythians with their bravery and courage, and battled both the Scythians and the Greeks. As a result, the Amazons were integrated into Scythian society, assuming important military and political roles and achieving social equality with men.

Some of Herodotus' accounts of the Amazons are steeped in legend, others contain traces of historical truth, but all are fascinating. For example, he claimed that the Amazons would not allow their daughters to marry until they had killed a man in battle.

The Amazons feature prominently in various Greek and European myths, like the Labours of Heracles. They have also permeated contemporary pop culture.

In creating Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston was inspired by stories of nomadic Scythian warriors. Another example of Scythian influence on modern imagery is Mixoparthenos, a half-woman, half-snake goddess worshipped by the Scythians of the Crimean peninsula - she is the figure depicted in the Starbucks logo. Thousands of years later and miles away, these warrior women are still with us.

6. From Ukraine's steppes to the Caucasian mountains: Greeks in Georgia.

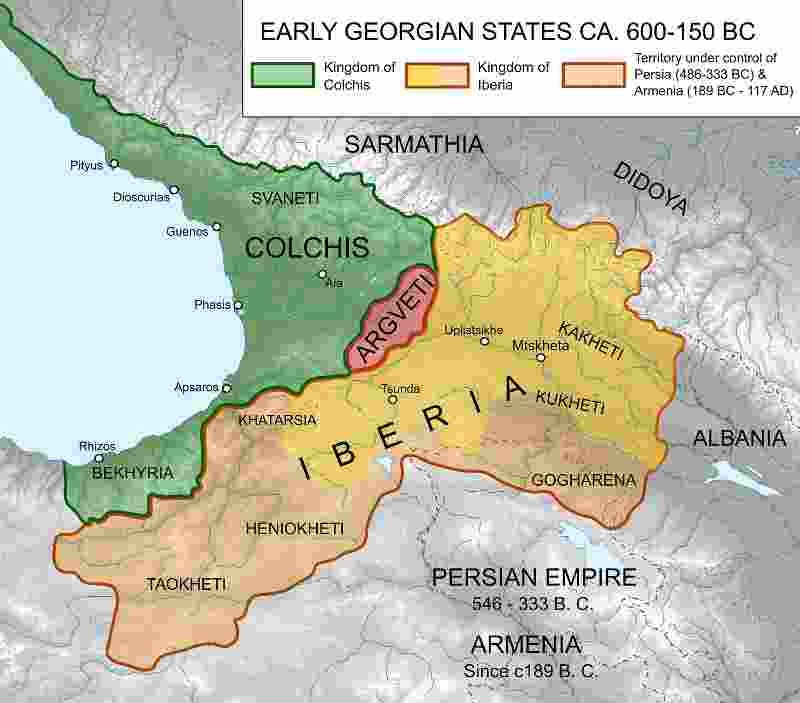

Jason and the Argonauts encountered the Amazons on their journey to the kingdom of Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece.

The Argonauts' quest for the Golden Fleece and the love story between the Greek hero Jason and Medea, the daughter of the Colchian king, is not only one of the oldest Greek myths. It is also the first time that Colchis, now Georgia, entered the Western imagination. Gold, wine and strong women were the hallmarks of Colchis.

The story of Jason begins in Greece and is a classic tale of revenge: his father, a king, was overthrown, but the son survived, hidden in the wilderness and raised by the centaur Chiron. As an adult, Jason sets out to reclaim his inheritance. To claim his rights, however, he first had to achieve the appropriate heroic stature. His challenge was to travel east, reach the kingdom of Colchis and retrieve the Golden Fleece.

After a long journey across the Black Sea, Jason and his crew, the Argonauts (named after their ship, the Argo), arrived in the legendary land of Colchis. More challenges awaited them there, but with the magical help of Medea, the daughter of the king of Colchis, Jason managed to steal the Golden Fleece and escape. He also took Medea, who had fallen in love with him, with him.

This marked the beginning of a conflicted tale of an Eastern woman trying to integrate into a society that viewed her as too powerful. Eventually, Jason left Medea to marry the daughter of the king of Corinth. In a fit of rage, Medea killed their children.

Colchis is more than just a land of myth; it was mentioned in Assyrian texts from the 12th century B.C. Several Greek and Roman sources give details of Colchis, located in western Georgia, noting the presence of developed roads, tiled houses, large cities and fortresses.

Greek colonies were also established there. These trading centres connected Georgia to Europe via the Black Sea until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Gold, iron, timber and honey were mainly exported to Greek cities. In return, Greek merchants exported pottery, wine, olive oil, textiles, bronze and silver goods to Colchis.

7. Rome: the Black Sea as a border.

In the 1st century BC, the Romans established control over the western Black Sea coast and southern Crimea. Their main naval base was Chersonesus, now Crimean Sevastopol. At the same time, they incorporated the Kingdom of Colchis as a Roman province and maintained eastern Georgia as a vassal state allied to Rome.

The Black Sea region provided the Roman world with resources, raw materials, and trade routes from the Caucasus and the Middle East. From Rome's viewpoint, it was not considered hospitable or a source of popular myth. Instead, it was primarily used as a perfect place for exiling unpopular aristocrats, artists, and intellectuals.

This was the fate of the poet Ovid, who was exiled from Rome to Tomis on the Black Sea by the Emperor Augustus in 8 AD. The author of Ars Amatoria spent the last decade of his life in exile in Tomis until his death around 17/18 AD.

Ovid characterized Tomis in contrast to Rome. He depicted the Black Sea as the boundary between Greco-Roman civilization and the tribes of the Ukrainian steppes and Caucasus. Ovid's negative portrayal, exaggerating the harsh winters and "barbarian" inhabitants, shaped Roman perceptions of the region. This stereotype, depicting the region as uncivilised and needing Western influence, influenced Enlightenment and Romantic travellers.

On the other side of the Black Sea, modern day Georgia became a battlefield between the Romans and the Persians, and later between the latter and the Byzantines.

8. Byzantium & Kyiv: Rivals and Allies.

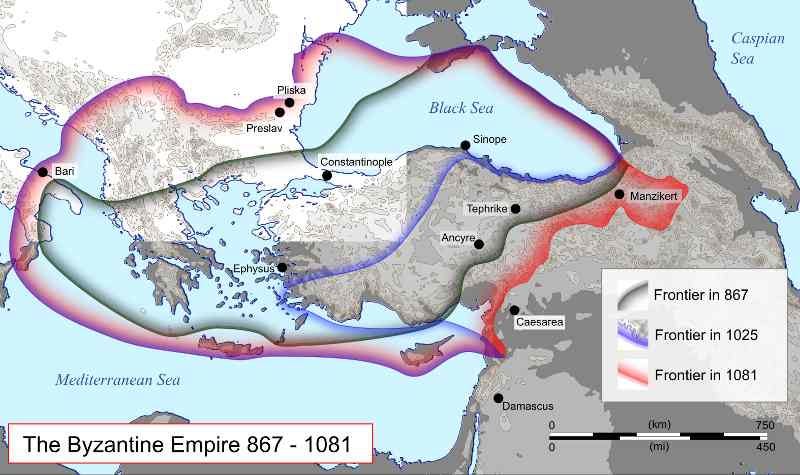

The major transformation of Rome around 1500 years ago, which included the transfer of power to Byzantium, is closely linked to events in Ukraine.

In the 3rd century AD, the Goths, a Germanic-speaking people from the Baltic and Vistula regions, arrived in the Black Sea area. They were the dominant power in the northern Black Sea area until the arrival of the Huns in 375. After being defeated by the Huns and driven out from the Ukraine region, the Goths moved westwards and crossed the Dabune, eventually becoming the famous Visigoths and Ostrogoths.

The Roman Emperor Valens had closed most of the Danube frontier in 369 and severely restricted diplomatic and trade contacts with the people of the Ukrainian plains. As a result, the Romans were unaware of the Hun invasions and were caught off guard when the Goths moved from Ukraine towards the Roman Empire. In 476 AD, the Germanic chieftain Odoacer deposed the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, symbolising the end of the Western Roman Empire.

Meanwhile, the Hunnic Empire collapsed after the death of its long-time ruler, Attila (c. 400 to 453). Bulgarians and Slavs invaded the northern Black Sea region and replaced the Huns.

Around the year 1000, the Vikings arrived in Ukraine and conveted to Christianity. They founded the state of Kievan Rus' and turned the Dnieper River into a major trade route between the Baltic and the Black Sea. Their main trading port was Korsun, on what is now the Kerch Strait.

Initially, the Kievan Rus' and the Byzantines had a contentious relationship, with the Rus' launching several attacks on Constantinople in the 9th and 10th centuries to secure trade concessions. However, the adoption of Orthodox Christianity by Vladimir I in 988 linked the Kievan Rus' culturally and religiously to the Byzantine world.

This link facilitated the spread of Byzantine architecture, art, literature and learning among the Eastern Slavs. The Cyrillic script used by the Rus' was based on the Greek alphabet, making it possible to translate Byzantine texts. The Kievan Rus' adopted elements of Byzantine administrative practices and imperial ideology, including the term 'tsar' (from the Lating Caesar).

Once converted, commercial relationships flourished between the two powers of Kyiv and Byzantium. The Rus' exported furs, honey, wax and slaves to Byzantium in return for luxury goods and manufactured products such as silk.

In 1240, the city of Kyiv (Kiev) was taken over by Mongol forces under Batu Khan after a siege lasting about nine days. At the time, Moscow was an insignificant village with less than a hundred years of history. Ca. two centuries later, Byzantium was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453. It wad the end of the Second Roman Empire.

In 1480, Ivan III defeated the dwindling Golden Horde (successor to the Mongol Empire) and declared Moscow the "Third Rome". This marked the beginning of Moscow's expansion eastwards and westwards. But that is another story.

Conclusion.

The Black Sea region and the Ukrainian Plain have played a pivotal role in many epochs of world history, from the foundations of agriculture, the spread of languages and ancient cities, to the inspiration for Greek mythology, the development of European states such as Kievan Rus' and the vicissitudes of Roman transformation. Georgia is at the root of Greek, and therefore European, founding myths. It was a place of longing, a "sensuous place", exotic yet familiar, distant yet accessible.

Certain places, such as the Straits of Kerch, the Dnipro River or the Crimea, have been of strategic importance since the time of the Greek colonies. The control or loss of these places marked the beginning of expansion or the beginning of decline.

The history of Ukraine and Georgia has been intertwined with Europe long before the concept of Europe existed. The territories now known as Ukraine and Georgia are, in fact, the origins of the fortunes, misfortunes and identities that have shaped Europe. Two centuries of Russian and Soviet Empire cannot change that. We come from there. They belong here.

Another fine post. I learn a lot from reading Beyond Berlin. Thank you.