April 25, 1945: when a small village became a symbol of the longing for peace.

In 1945, Soviet and American soldiers met on the Elbe. In 2025, that handshake’s meaning is being tested—by war, politics, and the fragility of memory.

The final weeks of World War II in Europe are crowded with dates we still remember. As this post goes live, it’s hard not to think of April 30—the day Hitler took his own life in his Berlin bunker, with Soviet forces closing in. Just weeks earlier, the world began to confront the full horror of the Nazi camps: Buchenwald was liberated on April 11, Bergen-Belsen on April 15. And ahead of us still lies May 8—Victory in Europe Day. A date that marked the official end of the war on the continent, and one we approach again this year with the uneasy sense that its meaning is being redefined and used as political weapon.

But 25 April 1945?

It tends to be overlooked. And yet, on that single day, the world began to change in ways that were both immediate and lasting. It was a day of history that happened all at once.

■ In Germany, after the brutal fighting at the Seelow Heights - where tens of thousands died in just a few days between 16 and 19 April - on 25 April Soviet forces closed the ring around Berlin. The final battle for the Nazi capital had truly begun.

■ In northern Italy, partisans launched a general uprising: the Committee of National Liberation called for a general insurrection against fascist and German forces. This decision would lead to the capture and execution of Benito Mussolini just days later.

■ Half a world away, in San Francisco, diplomats from dozens of nations gathered to open the founding conference of the United Nations - drafting the first outlines of a new world order, even as the war raged on.

All of this occurred on April 25, 1945—a lesser-known date of destiny.

To this date belongs the image many have seen: Soviet and American soldiers meeting on a bridge over the Elbe, near the town of Torgau (Saxony).

Smiling. Shaking hands. That handshake marked a real turning point - the moment when the Allies finally joined forces, north and south, east and west. That handshake, captured in black and white photographs—though admittedly staged a day after the actual events—came to symbolize something powerful: the hope that even amid the ruins of war, another kind of world might be possible. A world built, at least in part, on the promise of peace.

This is the story of that day—and what it left behind.

By late April 1945, the two great armies were moving steadily toward each other, knowing the war’s end was near.

To the east, the Red Army had crossed the Oder River after fierce, bloody battles and was now tightening its grip around Berlin. They had the strength to keep pushing west—but the agreements were clear: the Soviets would stop at the Elbe. To the west, the Americans had already halted at the Mulde River, a smaller waterway running parallel to the Elbe before merging with it near Dessau, about 150 kilometers southwest of Berlin.

Between the two rivers stretched a 30- or 40-kilometer-wide corridor—an intentional buffer zone designed to prevent accidental encounters or clashes.

Within this uncertain strip of land, American patrols combed the terrain for remaining German units, while scanning the far bank of the Elbe for signs of Soviet troops. With no aerial reconnaissance, the situation was chaotic. Soldiers relied on their eyes, instincts—and a simple signal system: green flares for the Americans, red for the Soviets.

On the morning of April 25, around 11:30, those flares were finally used.

A patrol led by Lieutenant Albert Kotzebue was out looking for German holdouts when they spotted a Soviet position across the Elbe. Signals were exchanged. A meeting was arranged.

The Americans made their way to the village of Strehla, about 30 kilometers south of Torgau, and crossed the river to reach Lorenzkirch—a scattering of farmhouses on the eastern bank. This wasn’t the place that would make the front pages or the history books. That would be Torgau, a few hours later, where a monument later was built.

Lorenzkirch, instead, would fade into obscurity. But it bore witness to something just as important—and far more tragic.

As German forces retreated, they had destroyed bridges behind them, even knowing that thousands of civilians were still fleeing west, desperate to escape the Red Army. The Americans crossed just two days later, landing amid a scene of horror: bodies of women, children, and the elderly littered the banks. Hit by both the Germans and the Soviets.

The Soviet soldiers welcomed them warmly—but the moment was too raw, too painful for celebration. So a new meeting was arranged, more official, more photogenic. The first handshake had happened here, but history would be recorded elsewhere.

There was a protocol to these encounters: first the soldiers met, then junior officers, then senior commanders. Each meeting moved a little further north. The one that entered the history books—the one in Torgau—was never officially planned. It happened because a young American lieutenant named Bill Robertson decided to reach Torgau on his own initiative.

Sometimes, history is a matter of timing.

Sometimes, it’s a matter of who dares to move first.

Why Torgau?

Today, Torgau is a quiet town of around 20,000 people—not exactly famous, but far from ordinary. It once served as the seat of the powerful Saxon Electors, who built a striking Renaissance castle that still draws visitors. For Protestants, Torgau holds special meaning: Martin Luther first preached here in 1521, and the first German baptism took place nearby in 1519. It’s also where Luther’s wife, Katharina von Bora, died and was laid to rest.

But in 1945, Torgau was known for a much darker chapter.

Two years earlier, the Nazis had made it the headquarters of the Reich Military Court—the highest judicial authority of the Wehrmacht. From that moment, Torgau became the nerve center of military justice in wartime Europe.

Its two prisons—Fort Zinna and Brückenkopf—held around 60,000 prisoners during the war: soldiers who had disobeyed orders, civilians accused of undermining the war effort, people condemned not by law, but by fear and ideology.

Beyond that, Torgau had little military importance. There were no critical factories, no strategic command centers. But as the war neared its end, Torgau was declared a “Festung”—a fortress. That designation came with grim instructions: either the town would be defended at all costs, or left but not before having blocked the enemy advance. How?

In the early hours of April 25, 1945, German engineers carried out one final order: they destroyed the two bridges across the Elbe. Then, the last Wehrmacht troops pulled out.

At the same time as the last German troops were pulling out of Torgau, Lieutenant Bill Robertson was leading a small American reconnaissance patrol. On a same mission as his comrade Kotzebue: check for any remaining pockets of German resistance between the Mulde and the Elbe rivers.

But along the way, he stumbled on something unexpected.

A group of British soldiers—ex-prisoners of war—had left Fort Zinna, the German military prison in Torgau. They told Robertson that Allied prisoners were still being held there. That was only partly true. Some sick or wounded inmates were still inside, along with other foreign prisoners. The rest had been sent off on forced marches, much like what was happening around the concentration camps during those final weeks.

By the morning of April 25, the German guards at Fort Zinna had abandoned the prison. The inmates, fearing crossfire between advancing armies, raised a Red Cross flag in the hope of avoiding attack.

Robertson could have radioed back and waited. But he didn’t. Acting on instinct—and against orders—he diverted his patrol straight to Torgau, hoping to free any remaining Allied soldiers himself.

When they reached the town, they found the Elbe bridge blown to pieces. On the far bank, Soviet troops stood watching.

There was a problem: the Americans had no green signal flares, the agreed sign to announce friendly intent. So Robertson improvised. He took a bedsheet, fashioned it into an American flag, and climbed one of the towers of Hartenfels Castle to wave it above the river.

But the Soviets didn’t respond with joy—they opened fire.

They had already been tricked once before by Germans raising a white flag. Suspicion ran high. It took a Russian-speaking American in Robertson’s patrol to finally shout across the river and convince the Red Army soldiers that these were, in fact, their allies.

Then, around 4 PM, on the broken remains of the Torgau bridge, Bill Robertson and Alexander Silvashko—walked toward each other.

They met in the middle, among twisted metal and rubble, and shook hands. It was an unscripted, uncertain moment—but it became a symbol. Soviet soldiers, now more relaxed, even followed Robertson’s patrol back to the American side. That evening, plans were made to meet again the next day. This time, with photographers and newsreel cameras ready. The world would soon see the handshake they had missed.

April 26 and 27: time to celebrate.

The day after these first encounters, regimental commanders from both sides met. On April 27, the commander of the 69th Infantry Division, General Emil Reinhardt, arrived in Torgau and crossed to the eastern side of the Elbe by rowboat. There he met Major General Vladimir Rusakov, commander of the Soviet 58th Guards Rifle Division.

Soon after, the media descended upon the scene. Around 70 reporters from American, British, and French newspapers gathered to document these historic events. The staged photos—including the one mentioned earlier—resembled more of a village feast than a moment of war. The footage captured the jubilant faces of ordinary soldiers from both armies.

Soviet memory made monument.

In the months that followed, the memory of that handshake at the Elbe quickly turned into something more permanent. To commemorate the meeting between the Allies, Soviet troops erected a monument in Torgau just five months later, in September 1945.

The task of designing it fell to a Soviet Army captain—Avraam Miletzki, a Ukrainian-born architect from Kyiv. The original plan was straightforward: top the memorial with a tank or a heavy artillery gun, a classic symbol of victory. But Miletzki had a different vision.

“In Torgau,” he said, “the weapons fell silent.”

So instead of showcasing firepower, he arranged rifles—stacked in a pyramid, as if abandoned after a battle—at the top of the monument. Around them, the lowered flags of the Soviet Union and the United States. Not triumph, but closure. Built with the help of local artisans, the memorial rose quickly—finished before the first postwar autumn had even ended.

Politics and memory during the Cold War.

After the war, Torgau—now part of Soviet-controlled Saxony—was absorbed into the newly founded DDR, the German Democratic Republic. Official memory was tightly managed by the ruling Socialist Unity Party, with Moscow keeping a close eye.

But far from the halls of power, one American soldier made it his mission to keep the memory of the Elbe handshake alive—not as a military triumph, but as a symbol of peace.

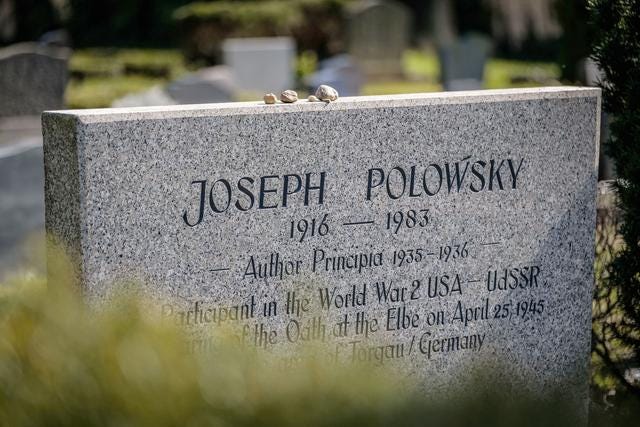

His name was Joe Polowsky.

A Jewish-American from Chicago, Joe was the son of immigrants who had fled the Kyiv region. His Russian skills made him invaluable during the war, and they landed him a key role on April 25, 1945—he was one of the first to speak to Soviet troops, standing on the ruins of the Elbe bridge.

But the war was just the beginning of Joe’s mission.

After returning home, he launched a quiet, personal campaign to transform the handshake into something greater—a universal Oath of Peace. He lobbied the United Nations to declare April 25 “World Peace Day.” The campaign failed, but Joe never gave up.

In 1955, ten years after the handshake, he visited Moscow with fellow veterans. Then in 1960—and again in ’61—he made his way back to Torgau, meeting East German leader Walter Ulbricht along the way.

But with the Berlin Wall going up and the Cold War hardening, he was soon cut off. After 1961, Joe was never allowed to return to East Germany. Still, each year, on April 25, he stood alone in Chicago—a quiet vigil in a city of millions, marking a moment the world had almost forgotten.

Before his death in 1983, Joe made one final request: to be buried in Torgau, in the town that had captured his heart in the final days of World War II. This time, East Germany said yes.

The burial took place in November 1983. American and Soviet soldiers stood side by side once more, laying wreaths as hundreds of onlookers watched. It became an international event, and to this day, the city of Torgau tends his grave.

Two years after his death, in 1985, the world marked the 40th anniversary of the Elbe meeting. Many U.S. governors declared April 25 “Elbe Day” in their states. U.S. Army representatives planned to attend ceremonies in Torgau, alongside peace activists and war veterans from both East and West.

But Cold War tensions had the final word. Just weeks before the event, in March 1985, U.S. Major Arthur D. Nicholson was shot and killed by a Soviet guard inside the GDR. The U.S. pulled out of the Torgau celebrations.

Still, the people came.

More than 25,000 gathered at the Monument of the Encounter. And there, in the midst of tension and hope, they renewed the Oath at the Elbe. Joe Polowsky wasn’t there in person. But his spirit was unmistakably present. And four years later, as the Wall fell, it finally seemed that the promise he fought for—that handshake he never let the world forget—had not been in vain.

The Nineties: Torgau keeps the spirit of the Elbe alive.

Since German reunification in 1990, Torgau has marked the 1945 Elbe meeting each year—not as a military commemoration, but as a celebration of peace. And every April, the town comes alive with music—especially jazz. The festival’s motto says it all: “Down by the Riverside.”

In 1995, on the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, the town took things one step further.

Torgau renamed its high school the Joe Polowsky Gymnasium, honoring the soldier who had turned memory into mission. That same year, both Bill Robertson and Alexander Silvashko—the two young men from either side of the Elbe who first shook hands—were made honorary citizens of Torgau. When the school closed in 2008, the town didn’t forget. Instead, they launched a new tradition: the “Joe Polowsky Memorial Run”, now held every spring by the students of Johann-Walter-Gymnasium.

Today, even the streets remember. The former school site is marked by a sign that reads “Joe-Polowsky-Hain”. And in the rose garden of Hartenfels Castle, a special bloom keeps watch: the “Polowsky Peace Rose”, planted on April 24, 2010. Visitors come every year. Crowds grow larger for the big anniversaries—1995, 2005, 2015.

But keeping the Spirit of the Elbe alive hasn’t been easy.

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and especially following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the hopeful handshake of 1945 has taken on a heavier weight. We’ve entered a new Cold War. And this time, peace feels fragile again.

2025: Joseph Polowski's betrayed dream.

It’s 2025. And Europe is at war—even if we still hesitate to say it out loud.

It’s 2025. And eighty years have passed since the bloodiest war in human history came to an end. An unlikely alliance between capitalist America and the communist Soviet Union brought it to a close. The peace that followed was imperfect—limited in geography, and fragile in its liberties. But it was peace. It was an achievement.

In the years after the Iron Curtain fell, anniversaries like Torgau became stages for something rare: reconciliation, respect, reflection.

Today, those anniversaries feel different.

This year, debates about how to commemorate the Elbe Meeting didn’t just stay in Berlin or Brussels—they arrived in Torgau. And something was lost along the way. As in past two years, Russia’s ambassador to Germany, Sergei Nechayev, arrived uninvited. He wasn’t alone. With him came bodyguards, fans—and members of Putin’s hooligan motorcycle clubs. Nechayev laid a wreath and made a familiar statement:

“Today we must remember the fallen soldiers. That is why this day is very important for us.”

But on his lapel was a symbol that now carries a different weight: the St. George’s Ribbon—once a mark of remembrance, now often paired with the letter Z, the emblem of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine.

Ukrainians were the soldiers who fought in this area, the ones who met the Americans here, the ones we see dancing and embracing the Allies in the photos of this post.

Saxony’s Minister President, Michael Kretschmer, chose not to ignore the moment. From the podium, he addressed the ambassador directly:

“Ladies and gentlemen, when we have met here in past years and decades, when you have commemorated this event, you have remembered and mourned. But no event that has taken place here, no handshake between an American soldier and a witness of the Red Army has occurred without them swearing: never again war.

War is the worst thing there is - never again war. And Mr. Nechayev, as you are here today as Russia's ambassador, I would like to be very precise about this message: it was Russia that started a war, not in 2021 but already in 2014, and it is up to Russia, only Russia, to end this war.”

The crowd’s reaction? Mixed. Some clapped. Others whistled—not at Nechayev, but at Kretschmer.

Who were they? Putin sympathizers? AfD supporters? Or just residents who had hoped for a quieter, more diplomatic ceremony—more “Spirit of the Elbe,” less confrontation?

I don’t know. But I know this: we have a problem. And in eight days—on May 8 and 9—we’ll all have to decide what that handshake in 1945 still means. What kind of memory we want to preserve. And what kind of Europe we want to keep building.

Post Scriptum

The United States declined to participate officially this year. “The U.S. Consulate in Leipzig is unable to attend the ceremony,” said a spokesperson from the embassy in Berlin.

But four American brothers still came. They flew in from Milwaukee. Their father had landed in Normandy at 19… and marched all the way to Torgau. They came not as diplomats, but as sons.

And that, too, is a kind of promise.

A personal, quiet Oath of Peace.

Nice post Valentina. I enjoy the way you merge the large-scale events with the smaller, more personal actions of individuals.