A journey through the language of freedom, from Athens and Rome to today's Ukraine.

There are many words for "freedom", but one stands out and has become even more powerful in recent years: the Ukrainian во́ля, "volia". A journey through languages and time, culture and arts.

MAKING SENSE OF OUR TIMES, ONE WORD AT A TIME

FREEDOM • FREIHEIT • LIBERTAS • ELEFTHERIA • SVOBODA • WOLNOŚĆ • VOLIA

Looking at the last twelve months or so, the list of books that have the word 'freedom' in their title is impressive. My personal list for 2024 is limited by the languages I speak and my interests, but it is significant: Freiheit (Freedom) by Angela Merkel; On Freedom by Timothy Snyder; Freiheitsschock (Freedom Shock: Germany 1989-2024) by Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk; Freedom: A Disease Without Cure by Slavoj Zizek. To these I would add books that have 'freedom' not as a title but as a core theme - the movement towards freedom (in the case of Garton Ash's pan-European narrative of Homelands) or the risk of losing it (Anne Applebaum's portrait of autocrats in Autocracy Inc.).

The word Freedom (Freiheit, Liberté, Svoboda, Свобода…) has never disappeared from our vocabulary. We all use it often, each in our own way. Everyone gives it their own meaning, and often one person's concept of freedom is in direct conflict with another's. Some see it as the right to speak without limits, to choose one's lifestyle, to pursue one's interests. Others interpret it as freedom from laws, norms, restrictions and rules. This creates confusion about the fundamental meaning of freedom.

Those of us in the free world face a paradox: we can comfortably debate the concept because we take freedom for granted. Only when freedom is threatened, or when we encounter those fleeing oppression, do we truly confront its meaning. Then, we must relearn the value of freedom from those who defend it in bunkers and trenches.

A journey through the language of freedom

Studying how different European languages express "freedom" and following its meaning through history and cultures reveals the essence of this concept and its relevance today.

Most of the languages spoken in Europe (and, by extension, the Americas) belong to the Indo-European family. This family descended from a single prehistoric language called Proto-Indo-European, which was spoken on the Pontic-Caspian steppe in what is now Ukraine – by tribes associated with the Yamnaya culture. Indeed: our languages migrated to us from Ukraine.

Indo-European languages fall into three main families: Germanic, Romance, and Slavic.The smaller but historically significant Hellenic family is also worth mentioning in this linguistic landscape. Our journey through time starts from Rome and Athens and travels to America and France, through the Germanic heartland of Europe and finally reaches the Slavic languages — where some stunning discoveries await.

Freedom in Athens and Rome:

the privilege of a select minority.

In ancient Greece, the term Ελευθερία (Elefthería) defined one's status in opposition to slavery. The Persian Wars strengthened this concept, as Greek city-states' freedom stood in contrast to Persian dominion. For these city-states and their free citizens (i.e. the non-slaves), freedom meant participating in democracy rather than living under tyranny. In this system, free male citizens not only had the right but also the duty to engage in political decision-making. Thus, freedom was the privilege of an elite group — those who could and must participate in governing.

In Romance languages such as French (liberté), Spanish (libertad) and Italian (libertà), the term "Freedom" comes from the Latin "Libertas". In ancient Rome, freedom was not a universal concept – Roman citizens enjoyed rights and privileges that distinguished them from non-citizens and slaves. Freedom was linked to citizenship and the right to participate in political life. Politically, Rome prided itself on being a “free republic”, in contrast to the monarchies of the East. This system, they believed, gave Rome a significant advantage that later helped it to develop one of the greatest empires in history. At an individual level, rights such as private property and freedom of movement depended on social status and citizenship - slaves, foreigners and women had no such rights.

Revolutions propel the word 'freedom'

into new realms of meaning.

Today we associate the word 'liberty' with universal human rights and justice. But this shift didn't happen until the Enlightenment. In medieval and early modern Europe, "libertas" existed primarily as a Latin term used by the Catholic Church. In Catholic doctrine, individual freedom wasn't valued for its own sake – Catholicism emphasised collective and individual order, with liberation referring mainly to freedom from suffering in the afterlife.

How did "liberty" become a revolutionary concept so central to modern societies? The ideas of the European Enlightenment found fertile ground in North America. When Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, declaring «We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness», he sparked a semantic revolution that emphasised individual rights (though still excluding slaves). This concept of "liberty" returned to Europe, inspiring the French Revolution and its motto «Liberté, égalité, fraternité». Back in Europe, liberty, combined with equality and fraternity, took on a more collective meaning than in the US - a difference that continues to shape our societies today.

From Community Protection to Individual Agency:

The Germanic Path to Freedom.

Meanwhile, the Germanic languages developed their own path to freedom. All related words - German Freiheit, Dutch Vrijheid, Swedish Frihet, and Danish Frihed - derive from the Old German "vrí" or "frí", meaning free. The Indo-European root *prāi-, *prī- means "to hold dear, to spare, to have a peaceful-joyful disposition", while the ancient Indian priyáḥ means "to own, to love". These Indo-European words reveal an ancient connection between freedom, peace and friendship. This development from "dear" to "free, independent", associated with peace and friendship, points to a protected space - family, tribe, principality - where peace prevails. Such freedom requires power to defend this space against competing spheres of influence.

The feudal structure of medieval Germanic societies emphasised personal relationships and obligations, shaping the understanding of freedom as a sphere of personal autonomy protected by the community.

The Lutheran Reformation marked a crucial shift towards individual freedom: by making human conscience accountable only to God, not earthly authorities, it established freedom of conscience. This gave rise to individual rights and freedoms throughout central and northern Europe, later reinforced by the Enlightenment philosophy of Immanuel Kant. His focus on human dignity and independent thought - «Sapere Aude»("dare to know", meaning: to think freely and form one's own opinions) - emerged from his essay "What is Enlightenment?" (1784) and became a guiding principle for the European liberal revolutions of 1848, the so-called Spring of Nations.

Freedom takes different forms in the Slavic languages:

Is it granted or conquered? Dependent or autonomous?

The answer lies in the word you use.

Across Slavic languages, the most commonly used word for freedom is Свобода (Svoboda). This word appears in Russian, Macedonian, Bulgarian, Czech, Slovak, Slovenian, and Ukrainian, with Serbian and Croatian using the variation "Sloboda" and Polish using "Swoboda". All these terms are inherited from the Proto-Slavic *svoboda. While today the word carries the same broad meaning as "freedom" in English, the history of Svoboda in Belarus, Russia and — to some extent — Ukraine reveals distinct paths in how the concept of freedom developed in these regions, compared to Freedom/Freiheit and Liberty/Liberté.

In the history of Russia, a sloboda was a settlement where people lived free from the power of the boyars — feudal barons who held the highest offices under the tsars. These were typically settlements of merchants and craftsmen, like the German Quarter in Moscow (nemetskaya sloboda), established for foreign settlers invited by the Empire. They also existed as colonization settlements in sparsely populated areas, such as the Cossacks in the Cossack Hetmanate. Initially, settlers in these sloboda enjoyed exemption from various taxes and dues — hence their name.

The term sloboda became associated with freedom granted by authorities rather than won through conquest. These concessions proved temporary: by the early 18th century, the Russian Empire had revoked tax privileges, and slobodas became ordinary villages, shtetls, towns, and suburbs. Though the 18th century marked the age of Enlightenment, in Russian-controlled Europe this movement wasn't homegrown but imported from the West under two absolutist rulers: Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) and Catherine the Great (r. 1762-1796). This explains why the concept of freedom, once imported by the Tsars, remained limited and never fully developed into individual rights to think, decide, and act independently.

Other words were needed to express freedom in more fundamental ways. The Polish language gave the word Wolność a profound mission: to express the highest value of freedom that Poles came to cherish — freedom as independence.

This applied both to the nation and its citizens, as well as to individuals who could determine their own destiny. Poland's history embodies this equation of freedom with independence. The country was forcefully divided between Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and Russia, existing without sovereignty from 1795 to 1918. Later, it was again occupied, partitioned, and devastated in WWII, then remained under the yoke of the USSR from 1945 until 1991, when the Warsaw Pact dissolved.

Za naszą i waszą wolność,

for our freedom and your freedom,

is one of Poland's unofficial mottos.

The motto gained prominence when Polish soldiers, exiled from partitioned Poland, fought in various independence movements around the world - including on the American side in the War of Independence (1775-1783). After this formative experience, the Polish fighters returned home to lead an uprising against Russia in 1794. The slogan appeared on their flags and became one of the most prominent battle cries during the November Uprising (1830-1831), also known as the Polish-Russian War of 1830-31. During that war, the slogan expressed the hope that a Polish victory would bring freedom not only to Poland but to all peoples suffering under the despotic tsarist regime.

The motto became dear to every Polish struggle against oppression, including the fight against Nazi fascism. Today, visitors to Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg district can find these words carved in marble on the "Monument to the Polish Soldier" in Friedrichshain Volkspark, erected in 1972 to commemorate the soldiers of the Polish communist underground Armia Ludowa (People's Army).

The Ukrainian word “Volia”: more than “Freedom”.

I come from a part of Europe where we speak four languages - Italian, German, Slovenian and Friulian - so I am familiar with all three major European language families. But a word like во́ля (vólja) was unknown to me until recently, and every time I encounter it I'm struck by the powerful idea it embodies.

Vólja means freedom, but its meaning goes deeper. The word comes from Proto-Slavic *voľà, which goes back to Proto-Indo-European *welh₁-. This is the same Indo-European root that gave us the Latin voluntas (and the Latin verb velle, 'to will'), with meanings of 'will', 'ardent desire' and 'choice'.

The Ukrainian word "Volia" has a powerful double meaning, combining both "freedom" and "will". It embodies personal autonomy while capturing the inner determination to overcome challenges. On a broader scale, it represents the collective strength of a nation to resist oppression and maintain independence against overwhelming odds - the shared will to be free, both individually and collectively.

It's more than a word; it's a philosophy of life and a reflection of collective consciousness. "Volia” illuminates much of what we've witnessed over the past three years: resistance, resilience and renaissance.

In the fascinating cultural-artistic project "Abetka" (Alphabet of Ukrainian Identity), writes Oksana Voytko:

«Volia is the ability to unite. When Ukrainians in just three days raised funds nationwide for Bayraktars, unmanned combat aerial vehicles, or organized aid for the Kherson region residents within a day after the explosion at the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station, they realized that all problems are shared, as well as solutions.»

«Nothing is impossible for volia-spirited Ukrainians. (…) Ukrainians continue to fight for volia, and the enemy does everything to take it away from them. However, they cannot grasp that volia knows no boundaries, it cannot be occupied or targeted by guided missiles.»

Source: A typeface alphabet of Ukrainian Identity, Projector Creative & Tech Foundation and ЗМІN Foundation

Volia is the essence from which Ukrainian people's resistance and resilience spring.

Yuval Noah Harari has been right in asserting, for three years now, that the Russian invasion has backfired: today Ukraine and its people are known worldwide, even among those Europeans who had negligently ignored them despite the past decade of overt conflict.

What brought Ukraine to the world's attention? Was it the armed resistance? The sacrifice of Azovstal in Mariupol? The tireless work of reporters and photojournalists?The wealth of new or republished books on Ukrainian history? Partially.

Ukrainian Volia has given rise to another form of resistance that has sparked a renaissance: culture - both past and present. The will to be free has turned into the will to create - writing fiction and poetry, producing theatre and music, developing video games and publishing comics, sometimes literally under bombardment and in shelters. And with it, the determination to share this culture.

Resisting through writing.

Whether under bombardment or without electricity for hours every day, Ukrainian literary life goes on. Over the past three years, bookstores have not only stayed open, but new ones have sprung up. Literary events, public readings and poetry slams continue throughout Ukraine. Writers, including those on the front lines, continue to write. New voices have emerged.

Many see the post-2014 literary scene as a Ukrainian renaissance. In recent years, this renaissance has gained international momentum, with many Ukrainian novels - not just those about war and displacement - being translated into English, German and other languages.

For those curious about Ukrainian literature but unsure where to start, I recommend subscribing to the Explaining Ukraine newsletter, edited by Kate Tsurkan at the Kyiv Independent. The newsletter covers Ukrainian culture and regularly reviews books and authors. It has become one of my favorite reads.

Also interesting to explore is Chytomo, covering publishing and contemporary literary and cultural processes in Ukraine in English: you will be amazed by the richness of literary productions, cultural debates, discoveries and discussions about both past and present Ukrainian culture.

If, like me, you're new to contemporary Ukrainian literature, Serhiy Zhadan is the essential author to start with, as his works have been translated into many languages. Zhadan wears many hats - novelist, poet, translator and rock musician. He grew up in Luhansk and later moved to Kharkiv, where he became one of the leaders of the local Euromaidan. Today he serves on the front line, while continuing to write, recite poetry and make music.

SEE ALSO: The New York Times, 24. Sept 2024, Ukrainian Poet and Rock Star Fights Near Front and Performs Behind It

His first international success was Voroshilovgrad, published in 2010. The novel is set on the outskirts of Voroshilovgrad (the Soviet-era name for Luhansk), where Herman, a young advertising executive, receives a disturbing phone call: his brother, who runs a remote petrol station, has disappeared. To find him, Herman must embark on an extraordinary journey, wandering across the steppe like a nomad. Together with his brother's loyal employees, two picaresque lads, Herman manages and defends the petrol station against Pastushok, a powerful local businessman - the novel's villain. Driven by nostalgia and a sense of justice, Herman chooses to stay in Voroshilovgrad, leaving his former life behind to face an uncertain future. Not sociological or political, Voroshilovgrad is ore about exploring how individuals reconcile with their past. Through its pages emerges a portrait of the Donbass region and its people, whose destinies are shaped by their harsh Soviet legacy. The book won BBC Ukraine's Book of the Decade award in 2014.

Zhadan continued to produce successful novels and poetry. In “The Orphanage”, readers follow a schoolteacher's journey across the frontline in search of his missing nephew during the 2014 war in Donetsk. The Orphanage is considered Ukraine's most important war novel about the Russian invasion. In 2023, “Sky Above Kharkiv” captured the world's attention: not a novel, but a curated collection of Zhadan's social media posts documenting the start of the full-scale invasion through intimate dispatches, as reviewed by Kate Tsurkan.

SEE ALSO: Kyiv Independent, 5 June 2024, 10 authors shaping contemporary Ukrainian literature

Resisting through imagination.

"The WILL" (which is the English translation of во́ля, vólja) is a series of Ukrainian fantasy graphic novels set during the rise of the Ukrainian state in 1918. This alternative history takes us back to 1917-1920, amidst a struggle for truth and freedom, where gunshots ring out and enemies lurk. The story features real historical figures of the Ukrainian national renaissance - Heteman Pavlo Skoropadskyi, Nestor Makhno (the "father" of the Anarchist Republic) and Mykhailo Hrushevskyi (the first president of the Independent Ukrainian Council) - reimagined as heroes in a steampunk world.

Since its debut in 2018, The WILL has become a bestseller in its category, developed a cult following, and expanded into a series with the release of the third volume in 2024. The franchise now includes board games, short films and spin-off graphic novels. While Ukrainian culture has deep roots, its modern expressions are as young as its demographics - comics and graphic novels have become major drivers of the local publishing market. "The WILL" shows how alternative history - as opposed to alternative facts - can help people reflect on their own past.

Resistance through the rediscovery of forgotten artists.

The web project "The Lost Treasures" profiles five female Ukrainian artists - all active in the 1960s, which marked the revival of Ukrainian culture after Stalin's repression, and all revolutionary in their artistic fields. All used their art to celebrate Ukrainian identity, and all faced persecution as a result. In the case of Alla Horska, her murder is considered an execution carried out by the KGB on the secret orders of the authorities. In the project you can read short biographies of Alla Horska, Halyna Zubchenko, Lyubov Panchenko, Lyudmyla Semykina and Halyna Sevruk, and browse through galleries of their work.

A pivotal moment shared by four of them is highlighted throughout the web showcase: in 1964, Horska, Zalyvakha, Semykina and Sevruk created a stained glass window entitled "Shevchenko. Mother" for the University of Kyiv. The work depicted the iconic Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko as an outraged artist defending an insulted woman who symbolised Ukraine. The stained glass was destroyed by the Soviet authorities immediately after its installation and its creators were prosecuted. Visit treasures.ui.org.ua

Resisting through music.

Music and festivals are life itself. The will to live life to the fullest is not a sign of indifference, as some have complained, but rather the opposite: Volya at its best. Many miles south of Ukraine, young people in Israel repeated "we will dance again" as a mantra against the cruel times they were enduring. Back in Ukraine, the Atlas music festival - Ukraine's largest and one of Europe's largest open-air festivals - returned for three days in July 2024 after being put on hold in 2022-2023. The stage was set up in a shopping centre car park, the only location with a shelter large enough to accommodate the 25,000 people expected in the event of an air raid.

New musical works continue to emerge during this time of war. Much of this music pays tribute to Ukraine's cultural heritage, particularly the rock opera project "Ty [Romantyka]". This work commemorates the Executed Renaissance - a generation of Ukrainian artists killed by the Soviet regime in the 1920s and 1930s. Working with contemporary artists such as the aforementioned Serhiy Zhadan, the project connects younger generations to this tragic chapter of Ukrainian history.

Resisting by sharing the will for freedom with the world.

During the 2024 Olympic Games, Ukraine showcased its culture through the “Volia Space” exhibition in Paris. This initiative promoted Ukrainian culture and raised awareness of the Russian invasion, while highlighting Ukraine's resilience and cultural identity. Throughout the Olympic weeks, the space hosted workshops on traditional Ukrainian cuisine, performances by singers and artists, meetings with athletes and film screenings - including the award-winning '20 Days in Mariupol' and several other documentaries.

On the occasion of Ukraine's third Independence Day since the full-scale invasion, an art festival in exile was organised in Berlin on 25 August 2024: ВОЛЯ [VOL.2] VOLIA. Hosted by Hotel Continental - Art Space in Exile, this centre for contemporary art in Berlin was founded in 2022 to support artists from Ukraine and other countries suffering from war and persecution. The one-day festival featured a rich programme of films, theatre, concerts, workshops and the closing ceremony of the exhibition "Wartime Posters". The exhibition featured works by contemporary Ukrainian graphic artists created during the war to counter Russian propaganda, boost Ukrainian morale and document military events and Russian war crimes against Ukraine. Before arriving in Berlin, these posters were exhibited in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, and several other European locations.

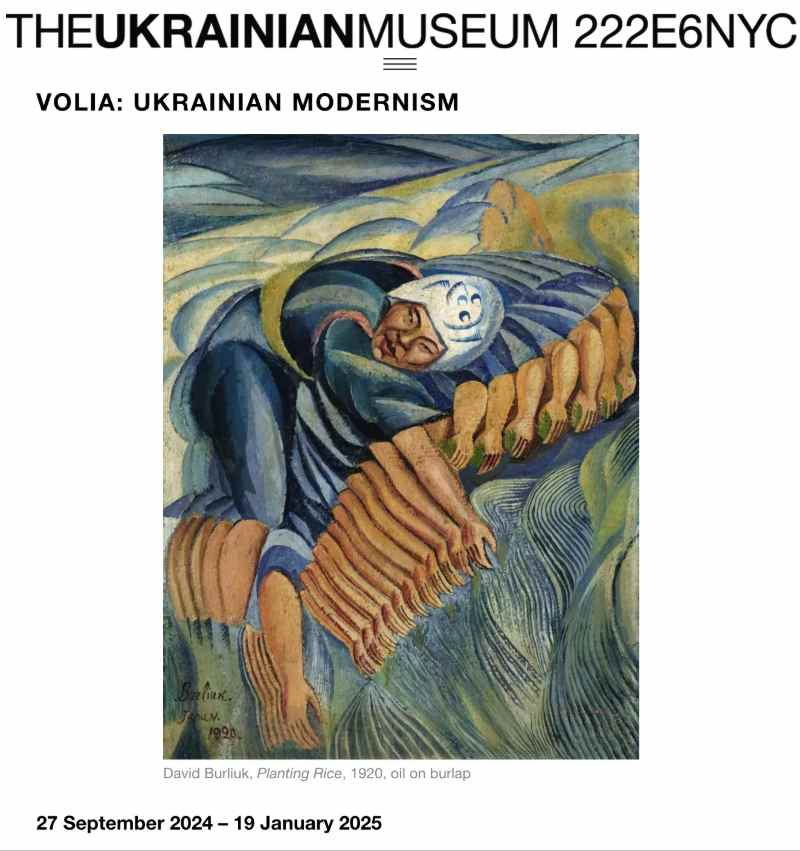

The Ukrainian Museum in New York is currently showing “Volia: Ukrainian Modernism”, an exhibition featuring prominent artists of the early 20th century. The works are presented in the context of the development, innovations and traditions of Ukrainian art and culture - elements that were suppressed and appropriated by Russian imperialism for decades. The curators argue that Ukraine's avant-garde movements, in breaking away from Soviet norms and reconnecting with Ukrainian cultural roots, perfectly embody the concept of Volia: the fusion of willpower and longing for freedom.

Conclusion: freedom + willpower = invincible.

Putin's pseudo-history, with its many distorted words, cracks when confronted with a word like Volia. Because freedom, as it has been forged over centuries on the Ukrainian steppes, is not about concessions. It's not about guaranteed spaces within closed communities. Nor is it something that can be exchanged for peace. Combined with will, freedom becomes invincible: it may suffer setbacks, but it never disappears. It radiates strength and inspires acts of resistance through books, poems, lyrics, performances and art that transcend national borders and time. The genocidal intention of the new Russian Empire has failed miserably. And it will continue to fail. Ukraine, meanwhile, has secured its rightful place in European history.

Suggested.

Reading these newsletter is itself an act of resistance.