Srebrenica: where were we all, when it happened?

11-17 July 1995: the Srebrenica massacre. Europe's darkest week and its devastating legacy. A genocide, a thirty-year funeral procession, surrounded by those who still attempt to bury the truth.

Everyone, age permitting, remembers where they were on September 11, 2001, the day of the Twin Towers. Me too. But who remembers July 11, 1995, the day of the Srebrenica massacre?

I do. I remember those days well. I was tearing up my master thesis. Deciding to rewrite it from scratch. Extending my university life by a whole year. I was confused. And also very, very angry.

Angry with my fellow university students in Milan. Angry at the indifferent Italians. Angry at Europe — where I had placed all my adolescent hopes since 1989. I was angry about what was happening in Bosnia, just seven hundred kilometers from my hometown in the extreme Northeast of Italy, bordering with former Yugoslavia.

Yes, the UN was there. With its resolutions. Useless then. Useless today. Yes, the peacekeepers were there. But they didn’t keep the peace. In the case of Srebrenica, they became part of the problem. Even NATO airplanes was there. In theory, enforcing a no-fly zone. In reality, just circling in the sky.

On July 11, 1995, they flew right over Srebrenica. They saw it all from above. People running, screaming, Looking up at the sky, hoping for help. But help never came. The Bosnian Serbs had taken UN troops hostage — Dutch and French soldiers. And they threatened to kill them. So the Blue Helmets did nothing. And the massacre began.

Where were we all?

Not just physically — but mentally.

Intoxicated by the fabulous eighties. Deluded that with the fall of the Wall, history was ending. We didn't notice that another history was beginning again. From the East.

When the Bosnian war broke out in April 1992, many were caught completely off guard. We had been lulled. By the dream of “Europe as a peace project”. We thought Europe meant Berlin, Paris, maybe Brussels. We forgot that Europe was also Belgrade. Zagreb. Sarajevo. Chisinau. Tallinn. Odessa. The Donbas. And in that Europe, the old ghosts were waking up. Yet someone already saw those ghosts. In the days following the fall of the Wall. And tried to warn us.

Ian McEwan, one of Britain’s great postwar writers, spoke at a conference in Milan in May 1990. And what he said still gives me chills:

“If the angel of democracy and self-determination has been set free, the demon of national differentiation is now also free… dragging behind it all the border struggleslong kept hidden and controlled by Moscow.”

He was clear. History hadn’t ended. It had only been unpaused.

“In 1989 not only countries were liberated: our past was also liberated.”

And right as the genocidal Bosnian war unfolded, McEwan’s novel Black Dogs was released — July 15, 1992. A story about Berlin. About Nazism in France. About how illusions died in a cruel century. A few months later, in an interview, he said:

"Those black dogs were the symptom of a wound that was reopening. They were alive, free, perhaps in Yugoslavia. They were the dogs used by the Nazis. Under different guises, those 'demons' would materialize elsewhere.

When the massacre began in Yugoslavia, I was in America. There, the problem of whether to intervene or not divided the country in two. Then, in Europe, I realized that the general tendency was 'not to get involved.'

It was then that I understood that the demons of the mid-century, which we believed had dissolved, had returned. As if what we thought we had buried had sprouted from the grass.

What we believed frozen had come back to life. As if many aspects and problems left by the Second World War had been paralyzed in the Eastern countries, while the heart of Europe—the West—was increasingly hardening."

Ian McEwan saw it. But we could all feel it. Something was about to explode.

After Marshal Tito’s death in 1980, Yugoslavia lost its glue. No more unifying figure. And in the middle of an economic storm, the cracks deepened. Slovenia and Croatia were richer, more productive. The southern republics were poorer, resentful. Old tensions resurfaced. In this fragile moment, nationalism came roaring back.

In 1986, the Serbian Academy published a memorandum accusing Albanians in Kosovo of planning genocide against Serbs. The signal was clear. The fuse had been lit. That same year, Slobodan Milošević rose to power. He understood the power of identity politics. He weaponized it. With communism collapsing, what was left? Only identity. And identity, once sharpened into a blade, cuts deep.

In June 1989, Milošević seized a symbolic moment: The anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo Polje—the Field of Blackbirds. He turned it into a nationalist spectacle. Kosovars were cast as heirs of the Ottoman oppressors. The Serbs? Victims once more.

Then, in 1991, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence. In southern Croatia, Croats and Serbs clashed. And that’s when the real plan took shape: Greater Serbia. Milošević and Franjo Tuđman, the Croatian president, met in secret. They agreed to carve Bosnia up. The multiethnic, multilingual Bosnia, where Muslims, Jews, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians had lived side by side for generations, didn't fit their plan. Ethnic lines would define the map. Everyone in their place.

Under the unfortunate advice of the European Community, Bosnia held a referendum on independence. Only 65% of the population voted—of them, 99% voted yes. Bosnia declared independence on March 1, 1992. Karadžić had already set up his own parallel filo-serbian state—Republika Srpska. And then came the horror.

On April 4 and 5, 1992, civil society in Sarajevo - of all ethnicities and religions - took to the streets to demonstrate peacefully against the imminent war. From the windows of the Serb independence party headquarters, two snipers fired and the first two victims fell, the two young women Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić. This marked the beginning of the season of terror against the unarmed population. In Sarajevo, sieged. And then throughout Bosnia. The violence and the war.

One week later, EuroDisney Park opened in Paris.

Where were we?

We were busy having fun.

Srebrenica: Chronicle of a Massacre Foretold.

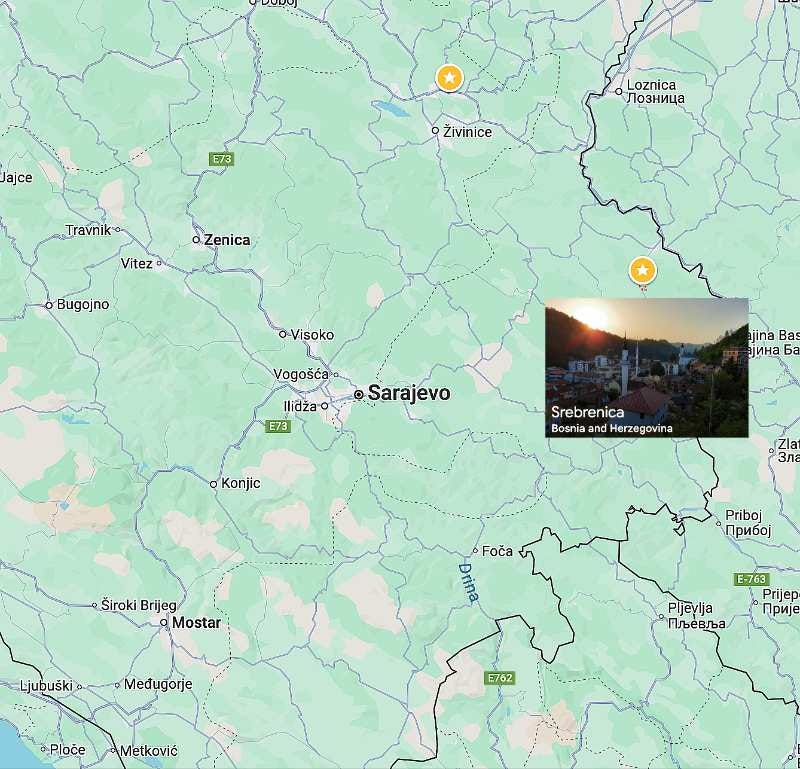

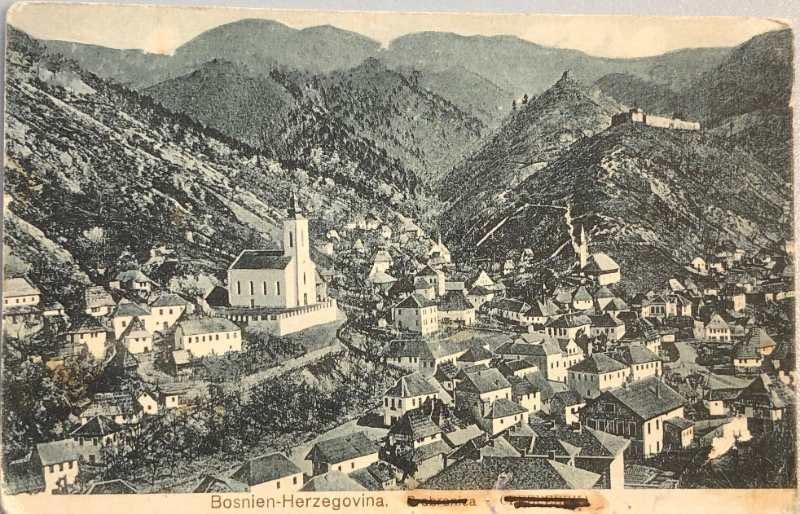

Srebrenica is a small town in eastern Bosnia, situated into a narrow valley near the Drina River. Serbia lies just across the border.

Once, it was known for its thermal springs. People came for rest, to heal. Low, wooded mountains. All in all, life there was good.

A battery factory in Potočari gave work to many. Serbs and Bosniaks lived side by side. They drank coffee, read newspapers, shared balconies. No one asked who was Muslim or Jew or Orthodox. It didn’t matter.

Then came 1992. Between April and June, Bosnian Serb forces swept through the villages. Paramilitaries. Hooligans. Local police. Backed by the Yugoslav army. They burned, looted, raped. Thousands fled. Srebrenica filled with 50,000–60,000 people—double its size. No food. No water. No medicine. A city under siege.

In March 1993, French general Philippe Morillon arrived with the UN. He promised protection. He said: “You are now under the care of the international community.” It gave people hope. But not much else. Supplies stayed low. The killing didn’t stop. Morillon had dinners with the besiegers in the evening. The same men whose troops were raping women in the dark nearby. He later said: “There was no smell of death.” But death was already on its way.

April 16, 1993: the UN declares Srebrenica a “safe area.” Demilitarized and protected. Two days later, 150 Canadian peacekeepers arrive in Potočari. Their orders? Prevent a takeover, secure aid, disarm fighters. But—don’t shoot. They were peacekeepers without a gun. Both sides broke the demilitarization deal. The Serbs never withdrew their weapons. Bosnian defenders hid theirs too, launching desperate raids.

In March 1994, the Canadians left. Dutchbat took over—600 Dutch soldiers, poorly supplied, under-trained, without clear command.

Another year passes. It's 1995. The war has been going on for more than three years. Europe is beginning to tire. The world wants to turn the page. Sound familiar?

The U.S., under Bill Clinton, pushes for a solution. Partition. Muslim areas here. Serb areas there. But the eastern enclaves—like Srebrenica—don’t fit. They’re Muslim-majority, surrounded by Serb-held land. Karadžić doesn’t want to give them up.

In March 1995, he tightens the siege. No more aid. No more food. And behind the scenes, the UN prepares to withdraw. All in the name of “neutrality.”

It was clear: The price for peace would be abandoning the enclaves. Including the people inside. Territories in exchange for peace—does that sound familiar, too?

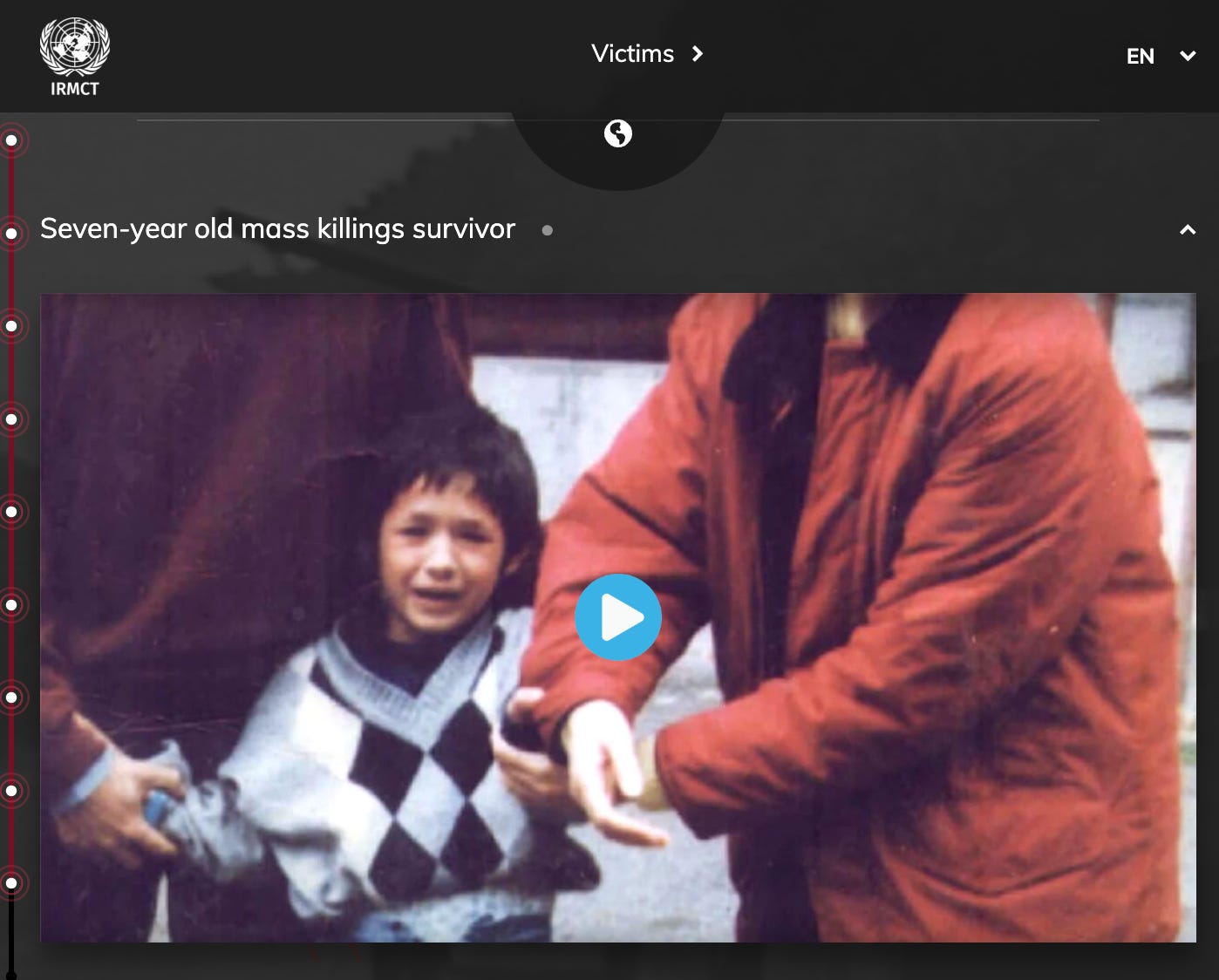

HERE THE VIDEO DOCUMENTATION OF THE EVENTS UNFOLDING

IN SREBRENICA DAY BY DAY, GATHERED BY THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA. A MUST-WATCH, ESPECIALLY FOR THE YOUNGER.

July 6, 1995: Ratko Mladić, the butcher of Srebrenica, attacks. Serbs break through UN lines. They take the Dutch peacekeepers hostage.

July 10, 1995: Colonel Thomas Karremans, commander of the Dutch battalion, desperately requested NATO air intervention. That evening, a radio amateur from Srebrenica sent out a desperate call for help. All radio amateurs in south-central Europe heard it. Even in Italy. From our side of the Adriatic.

July 11: NATO responds. Sort of. After dropping only two bombs that destroyed a single tank, they flew away. Mladić had threatened to kill the hostages. NATO backed off. Mladić enters Srebrenica. He hands out chocolates to children. Smiles for the cameras. Promises safety.

20,000-25,000 Bosnian refugees gathered at the Dutch compound in Potočari. Seeking protection. The peacekeepers initially refused to open the gates. But the crowd broke through the fences. Mladić arrives. He asks to separare the men and boys from the women. Ages 12 to 77. The Dutch hand over to the Serbs 350 Bosnian men who had managed to slip inside the base.

Meanwhile, around 12,000–15,000 men attempt to flee through the forest. They trek toward Tuzla—110 km away. Their path is fraught with ambushes, snipers, and hunger. It becomes a Death March, a "Todesmarsch." Only some make it.

Inside and around the UN compound, horror unfolded. Rapes and killings began. The peacekeepers witnessed these atrocities but did not intervene. Fadila Efendić, one of the survivors, described the UN base as "a scene from hell." People were giving birth, dying of fear, and committing suicide—all while Serbian soldiers operated undisturbed.

Then came July 13. Systematic executions began. Thousands of men and boys were taken. Often with their hands tied and eyes blindfolded. Brought to various improvised detention sites. Warehouses. Farms. Schools. Gyms. And then executed.d. Mass graves were dug in a rush. Then dug up again. Bodies moved, scattered, dismembered. To hide the crime. By July 17, no Muslims remained in Srebrenica. Over 8,000 men and boys killed. In one week.

And where were we? In Europe, we were watching the final stages of the Tour de France on TV. America was dealing with a heatwave in the Mid-West.

Only weeks later, satellite images by American Intelligence revealed the truth. Large patches of disturbed earth. Indicating the presence of mass graves. But the job was done. The enclave was gone. Ethnic lines redrawn. Peace could begin.

In November 1995, the Dayton Accords ended the war, dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina into two entities: the Croat-Muslim Federation (51%) and Republika Srpska (49%).

This effectively sanctioned "ethnic cleansing." Srebrenica—site of Europe's worst atrocity since WWII—was assigned to Republika Srpska, handed over to the very people who had committed this crime.

In 2004, the massacre was declared genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. In 2007, the International Court of Justice confirmed it.

Karadžić and Mladić were eventually tried and sentenced. Milošević died before his verdict. But the tribunal was closed in 2017. Only 18 convictions. The small fish—those who pulled the triggers, lit the fires—walk free. Some are still on trial in Belgrade. But these trials that may never see an end.

For the families of the dead, another chapter began. For them, another question emerged. No longer "Where were you?" or "Where were we?". A harder one: “Where have you gone?” “Why aren’t you here?”

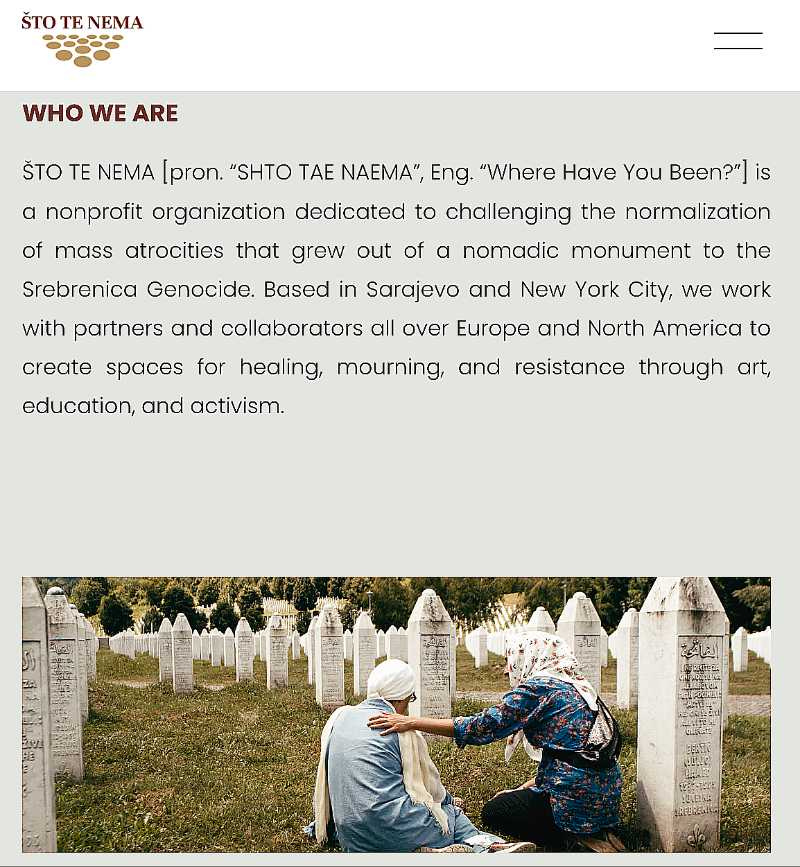

“Što Te Nema” – “Why Are You Not Here?”

There's no perfect translation for the Bosnian phrase "Što te nema." You can say: "Why are you not here?" or "Where have you gone?".

But neither captures the full pain behind those words. It's not just absence. It's longing, loss, a wound that never closed. The pain of absence. "Where have you been when we needed you?" "Why are you not here today, when your presence is missed the most?" "Why are you not returning?" It's the title of a beloved Bosnian song—a hymn to those who are gone, and to those who still wait. At the end of this post, you'll find a version of that song.

It’s the question that thousands of families have been asking for thirty years. Not only in Bosnia, but around the world. Because the war created a diaspora. Today, more Bosnian families live abroad than at home.

One of them is the family of Aida Šehović, born in Banja Luka in 1977. She fled in 1992. Istanbul. Germany. Then the United States. She became an artist. But not to escape reality. To remember. To give shape to what was lost— and to what still hurts.

Because how do you remember when bodies are still missing? How do you remember when families are scattered? When coexistence itself has been buried?

In 2006, Aida began collecting fildžani— the small handleless porcelain cups used for Bosnian coffee. One for each of the 8,372 victims.

In Bosnia, coffee isn’t just a drink. It’s a ritual, a gesture of welcome, shared with guests, family, friends. Coffee was and still is the way to welcome guests. You drink a first cup. Then a second. Usually there's always a third round if the conversation continues. A family and collective ritual.

Aida reached out to the Mothers of Srebrenica Association. Together they gathered the first 923 cups. From family to family, the collection grew. And a new kind of monument was born.

Each July 11, Aida would bring the cups to a different city. Volunteers and passersby helped lay them down in public squares. Each cup filled with Bosnian coffee— but never drunk. Because the ones who should drink it— never came back.

From Sarajevo to New York, from Geneva to Istanbul, from Toronto to Venice Biennale, for fifteen years, this living monument traveled the world.

And then, in 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, it returned home. With more than 8,372 collected cups assembled at the site of the atrocities in Srebrenica-Potočari.

To the cemetery where almost 7,000 victims now rest. To the place where so many are still missing. More than a thousand bodies remain unidentified. Their pieces, what remains, lie in a warehouse on steel shelves. Enclosed in white plastic bags.

A space where grief has no end. Where even a ritual like this becomes unbearable. That homecoming, and the weight of all those absences, is now told in a documentary film: “Što te nema.”

Since 2024 the film has been traveling around Europe with public screenings in Sarajevo, Ljubljana, Munich, Biarritz, Graz in Austria, Berlin— and this July, to Biograd na Moru in Croatia.

Aida always says: this isn’t just about one genocide. It’s a call to remember others— past and present. And to do something to stop them.

Today, while I am writing, the installation is in The Hague, at the Kunstmuseum, where Aida and architect Arna Mačkić are building a permanent home for it. The last journey, perhaps, for these eight thousand cups. Their ultimate challenge. And it will be a difficult one.

Because where they should live forever, Srebrenica, that is Republika Srpska. There where people gather every year. This year even the memorial center of the massacre had to temporarily close its doors for lack of security requirements. The Serbs still deny. The Serbs still threaten. And Bosnia Herzegovina today is not just a country divided in two. Every place has its internal borders. Coexistence has been killed forever. In the heart of Europe.

And yet, on July 11, the relatives of the victims will come. As they always do. To bury their loved ones. To hold another funeral. Because this is a funeral that has lasted thirty years.

This year, they will bury Fata Bektić, 67. Her remains were found in a mass grave twenty-six years after her death. They waited, hoping more of her could be recovered. She will rest beside two nineteen-year-olds—Senajid Avdić and Hariz Mujić. And others: Hasib Omerović (34), Sejdalija Alić (47), Rifet Gabeljić (31), Amir Mujčić (31). Only a few bones remain of most of them. They were found in mass graves. Now, finally, they are being laid to rest.

A funeral thirty years long.

A shame thirty years deep.

For those who were there. And did nothing.

For those who looked away. And forgot.

The Song "Što te nema"

Mostar Sevdah Reunion is a world-fusion musical ensemble from Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina that performs primarily the Bosnian traditional Sevdalinka genre, blended with contemporary musical styles. They are proudly mixed and multiethnic, as Bosnia used to be.

This is their heart-wrenching interpretation of "Što te nema".

Per lettrici e lettori in lingua italiana. C'è un podcast di Chora Media che è un piccolo capolavoro, scritto e raccontato da Roberta Biagiarelli e Paolo Rumiz. Mi sento di raccomandarlo di cuore: https://choramedia.com/podcast/srebrenica/. Raccomando anche questa lettura: https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/aree/Bosnia-Erzegovina/Srebrenica-una-ferita-aperta-238960