Cosmic Dreams, Earthly Ambitions: Reflections on the Space Race Narrative.

As geopolitical tensions rise again, a new space race emerges. But can today's competitors create narratives as inspiring as those that captured imaginations during the Kennedy-Khrushchev era?

On September 12, 1962, on a warm and sunny day, President Kennedy delivered a speech to a crowd of about 40,000 people at Rice University's stadium. He addressed the space race, its motivations, and its ambitious goals—chief among them, reaching the Moon by the end of the decade:

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own.

Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war.

I do not say that we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again.

But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.

(Source: JFKlibrary.org)

There was a time when the space race inspired a powerful, emotional, and progressive narrative. It was a narrative that spoke of progress, the value of science, and optimism in human potential. True: this narrative was also propaganda. The space race and its narratives were an integral part of the Cold War. But both American and Soviet narratives were beautiful and inspiring, drawing from timeless stories of heroes - some to be admired from afar, others with whom one could actually identify.

Though ideological, these narratives reached beyond mere flag-planting or territorial conquest. They spoke of transforming the world itself.

These stories, which we've inherited or, depending on our age, remember firsthand, didn't emerge from a better time—how could anyone call the Cold War era better? - but they fostered better sentiments. In their speeches, both Americans and Soviets consistently presented space exploration as a path to worldwide peace and prosperity, not just national glory. This spirit was evident when, months before Kennedy's "We choose to go to the Moon" speech, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev wrote to President Kennedy, congratulating him on the successful launch of a manned spaceship. He wrote:

It is to be hoped that the genius of man, penetrating the depth of the universe, will be able to find ways to lasting peace and ensure the prosperity of all peoples on our planet earth which, in the space age, though it does not seem so large, is still dear to all of its inhabitants.

If our countries pooled their efforts--scientific, technical and material--to master the universe, this would be very beneficial for the advance of science and would be joyfully acclaimed by all peoples who would like to see scientific achievements benefit man and not be used for "cold war" purposes and the arms race.

Please convey cordial congratulations and best wishes to astronaut John Glenn.

N. Khrushchev (Source: Department of State Archive)

It was propaganda, sure. But it was well done.

I've been reflecting on this lately: when I watch news reports about launches of recyclable rockets, I no longer see heroes - the scientists, astronauts, and engineers, women and men. Instead, I only hear about billionaire owners and financiers who treat mission failures like the temporary stop within a casual video game - game over, restart, get to the next level, level down, level up... I watch as they announce the return to Mars as a destined mission to plant national flags... “And we will pursue our manifest destiny into the stars, launching American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars. (Applause.) Ambition is the lifeblood of a great nation, and, right now, our nation is more ambitious than any other. There’s no nation like our nation.” (White House)

And I feel no emotions, neither positive nor negative: neither admiration, nor inspiration, nor envy or anti-American sentiment, as I've never been and never will be anti-American. Instead, I feel nostalgic for my childhood spent in the shadow of the Iron Curtain - though from the Western side, protected by the Americans to whom I remain grateful. There, in Europe's easternmost edge of Italy, where languages and stories intermingled, I grew up with space tales that truly sparked imagination.

These stories came from both sides of the divide, and many of the most captivating ones came from the East. And these stories, tucked away in some corner of my memory, have resurfaced in recent years through the places I've visited as an adult, especially since living in and travelling through the former East Germany. It is here that the grand Soviet narrative of space conquest has left traces that are still alive today, often surprising ones.

Gagarin is still everywhere.

On one of my first visits to Berlin in 2004, I discovered a bar in Prenzlauer Berg that film experts had told me about—during GDR times, it had been a favorite hangout for the neighborhood's bohemians, with scenes from the cult film "Solo Sunny" filmed there. When I arrived, it was called Bar Gagarin. Between 2004 and 2014, I spent countless afternoons and evenings there, always choosing the same spot against a large wall decorated with a mural inspired by Yuri Gagarin's most famous portrait.

Gagarin was one of the greatest Soviet myths in cosmonautics—as they called it in the East, rather than astronautics—who became a global icon in 1961 when he became the first human to fly into space aboard Vostok 1. This marked just one of many pioneering achievements the Soviet world would accomplish during that era. The West found itself struggling to comprehend how a nation still recovering from World War II's devastation could make such swift advances toward space exploration. In 1957, the Soviet Union made history when Sputnik became the first artificial satellite to orbit Earth—a name now familiar to us all.

Gagarin's achievement filled the Western world with both admiration and fear. In the East, another aspect of the Soviet space narrative would leave an indelible mark: Gagarin was truly a man of the people. Born to working-class parents - his father a carpenter on the local kolkhoz, his mother a milkmaid - both had survived deportation to Germany as forced labourers during the war. His quiet, unassuming manner and friendly personality endeared him to many. Although his historic flight failed to complete a full orbit, he was subsequently barred from further space missions to protect his iconic status. Still allowed to continue as a pilot officer in the Red Army, he continued his flying career until 1968, when he died in a MiG aircraft accident. This tragic end only served to cement his legendary status forever.

The Bar Gagarin is now gone, replaced by a Vietnamese restaurant. But Gagarin's legacy lives on - at least 35 streets in East Germany still bear his name. In Berlin, on the aptly named Allee der Kosmonauten in the far eastern suburbs, a huge mural by artist Victor Ash is a testament to this enduring influence. He created it as part of a celebration of the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Wall in 2019:

After his historic spaceflight, Gagarin embarked on a career as an ambassador for socialist space achievements, which brought him to Erfurt, Thuringia, in 1963. The visit was broadcast live on GDR state TV, featuring memorable moments—including when an enthusiastic spectator hugged and kissed Gagarin in Erfurt's Thüringenhalle. The city's admiration was so profound that they renamed streets, neighborhoods, schools, and buildings in his honor. The Mao-Tse-Tung-Ring street became—and remains today—the Juri-Gagarin-Ring. In 1980, the "Kosmos" Hotel (now Radisson Sas) opened, with its halls themed around space achievements both in name and design. German astronaut Siegmund Jähn, who in 1978 became both the first GDR citizen and the first German in space, later inaugurated a bust honoring Gagarin in front of this hotel.

Though many place names have changed since then, locals still know this area as "Gagarin Stadt," and it was fittingly adorned with an artistic mural a few years ago:

Valentina Tereshkova

Along with Gagarin on this ceremonial tour through East Germany was Valentina Tereshkova, another unforgettable figure, though politically controversial today. Tereshkova had just completed, on 16 June 1963, at the age of 26, her first space mission, and the first orbital mission by a woman in the world.

A textile worker and parachutist, later qualified as an engineer, small in stature but incredibly strong - today, at 87, still in great shape - Valentina Tereshkova, like Gagarin, embodied the "girl next door" and symbolized the upward social mobility that the Soviet Union promised. And importantly—she was a woman! Historians still debate the reality of gender equality in the socialist world, both in the Soviet Union and former GDR. While it fell short of their idealistic claims, it undeniably surpassed what existed in the Western world at the time.

Tereshkova's success demonstrated that women could succeed in traditionally male-dominated fields, making her an inspiring role model. Countless times in the not-so-distant past, when I introduced myself as Valentina, people exclaimed, "Of course! You're named after Valentina Tereshkova" - and not just those of Soviet origin, but many from my own part of the country. They would then go on to recount the remarkable achievements of this petite but pioneering woman.

Here in Berlin, people occasionally remember Tereshkova's visit as guest of honour at a friendly football match between East Germany and Hungary in 1963. Like many Soviet heroes, Tereshkova had streets named after her and received numerous tributes.

But unlike those immortalised by early death, those who live long sometimes tarnish their own legacies. Today, as a senior member of the Russian Duma in Putin's party and a vocal supporter of the invasion of Ukraine, Tereshkova has fallen into disgrace in the West. A telling silence has fallen over her name, while places that once commemorated her - such as in the Czech Republic - have been stripped of their monuments.

The former Potsdam Data Centre

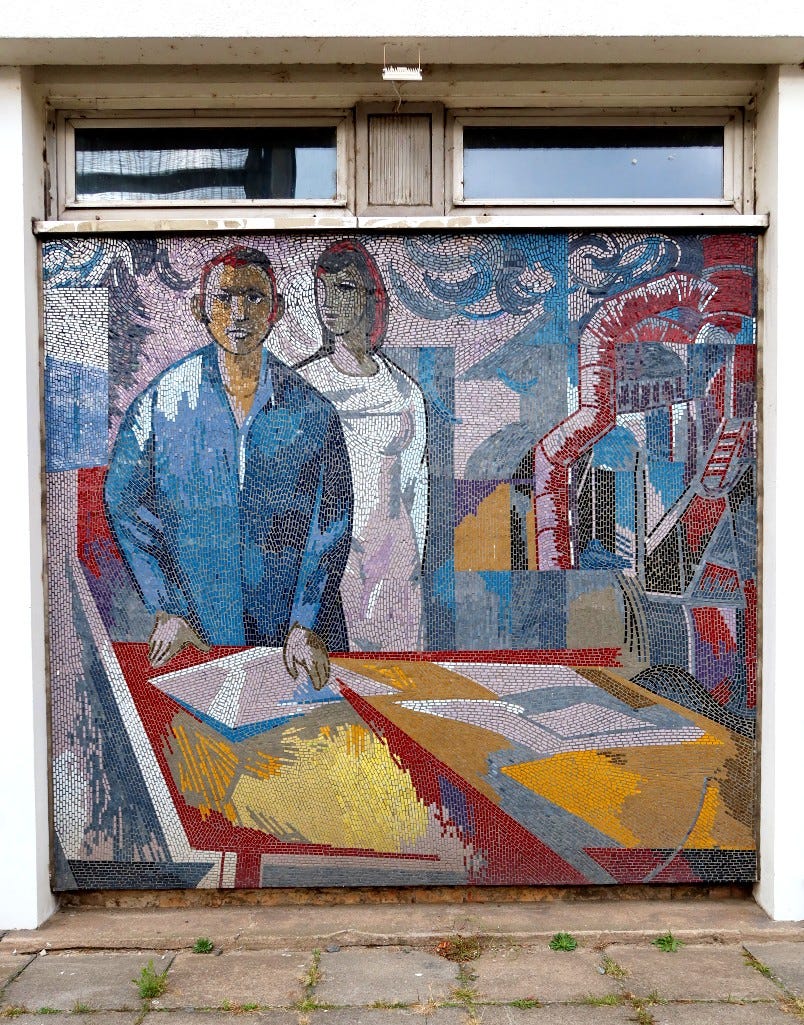

Women and men worked side by side—some analyzing data, others venturing into space—all united in building a future of peace and progress. Perhaps nowhere in the former DDR world captures this narrative more perfectly than the mosaic adorning three sides of the former Potsdam Data Centre (Rechenzentrum). This slightly weathered yet remarkable artwork, built between 1969 and 1971, stands in downtown Potsdam, just a 15-minute walk from the train station.

The mosaic cycle "Man conquers the cosmos," created in 1972 by artist Fritz Eisel, is approximately 60 metres long and consists of 18 panels, each measuring approximately 3.30 m × 3.00 m. One panel celebrates Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, who made history in March 1965 by leaving his spaceship and floating freely in space for 12 minutes:

Other panels honor the dedicated computational work of women and men, depicted with relatable faces that anyone could identify with and aspire to emulate:

And then, of course, there were the rockets:

Women's scientific contributions were highlighted in a dedicated panel:

It's a secular and socialist equivalent of the pictorial cycles in Italian medieval churches—each panel conveying a message, each message serving as inspiration. When I say this narrative was moving—propaganda or not—it's also because it blended science with art in a way rarely seen today.

A Red Star on the Red Planet

When examining the Soviet space narrative, it's worth noting that this fusion of science, propaganda, and art predates the Cold War era. Like elsewhere—as seen in Jules Verne's novels—space exploration captivated philosophers, artists, and storytellers throughout the 19th century. The 1917 Russian Revolution accelerated this movement, igniting utopian visions. Revolutionaries imagined their movement would spread worldwide, uniting all proletarians in a "red world storm" to transform society. They envisioned this world revolution breaking down borders and unifying humanity, ultimately turning Earth into a "red planet." The cosmic vision enhanced this dream, promising advancement into new galactic frontiers.

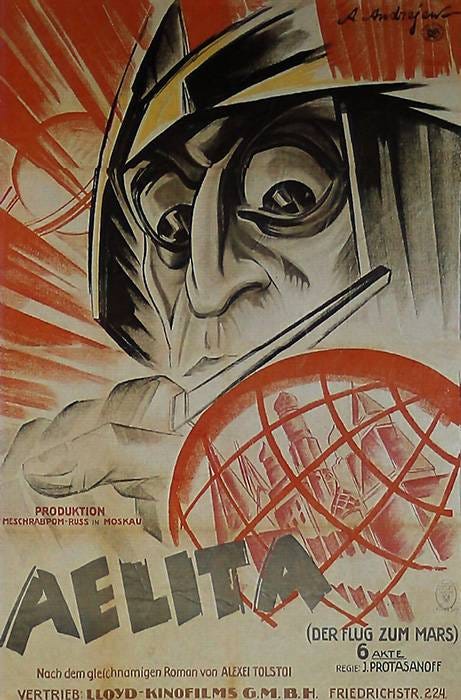

Cosmic enthusiasm spread beyond Bolshevik propaganda into mainstream culture. The avant-garde embraced space themes in art, literature and architecture, to reach the cinema. A new genre of socialist science fiction literature emerged, led by Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy.

Based on his novel Aelita (Russian: Аэли́та), a silent film adaptation was released in 1924: the first Soviet science fiction film. The success of this film was such that it attracted the attention of American distributors, who released it in the USA in 1929 under the title Aelita: Revolt of the Robots.

The film is set in 1921, during the final days of the Russian Revolution - a time of chaos and widespread poverty. The story begins when radio stations across Europe receive mysterious signals from outer space containing the unintelligible words "Anta Odeli Uta". Engineer Los orders Soviet military experts to decipher the messages. When Los suggests that they might be coming from Mars ("It sounds crazy, but someone on Mars is wondering about us"), his colleagues scoff. Fascinated by the idea, Los begins to daydream and draw up plans for a spaceship to reach Mars.

Meanwhile, everyday life in Moscow is harsh: people endure reduced rations, cramped communal living and interpersonal conflicts. Although there are moments of solidarity in times of need, food theft and embezzlement are common. To escape this grim reality, Los retreats further into his fantasies of Mars. He imagines its queen, Aelita, observing Earth through her telescope, while he observes her through his own. As their parallel dreams unfold, the story weaves through multiple narratives until Los finally realises his vision: to build a spaceship and travel to Mars to meet Queen Aelita.

When they arrive, Mars' ruling Council of Elders orders the Earth visitors to be killed, seeing them as dangerous revolutionaries who might disrupt their slave-based society. Queen Aelita intervenes, allowing them to land safely, and falls in love with Los. Meanwhile, a slave uprising begins. The revolutionary masses storm the Martian Winter Palace and overthrow the Council of Elders. Queen Aelita initially supports the revolution and leads the slaves to victory. After their triumph, however, she betrays the cause and begins a restoration - ordering the slaves to disarm, proclaiming herself absolute ruler, and ordering the now-loyal Martian army to force the slaves back into captivity. Enraged by her treachery, Los turns on his lover and throws her down the palace stairs to her death.

While trying to fathom the meaning of the words "Anta Odeli Uta", Loss suddenly wakes up in the main story and realises that the journey to Mars was just a daydream.

A red, revolutionary, galactic daydream.

A dream about… red Stars on the red planet.

Back to East Berlin, where space is encoded in architecture

Heading back home after this excursion, I smile thinking about how I've grown accustomed to passing almost daily under two monuments to Cold War space narratives. Despite Alexanderplatz not being my favorite place—too many people, too much chaos, too much everything—I've grown fond of these landmarks like the familiar objects in grandmother's living room: not always in good taste, but comforting.

The profile of the Berlin television tower, the tallest building in Germany and fifth tallest television tower in Europe, has become a reassuring sight. It's impossible to miss, and when I begin the landing approach to the city by plane, spotting it feels like seeing my home's gate—I am back! The tower has stood there since 1969, bearing witness to great stellar ambitions, watching one world collapse and a new one rise.

And then there's the sweetness of that internationalist—or perhaps imperialist—symbol of the world clock, which displays on its metal rotunda the names of 146 places across the planet, many belonging to the Soviet world. Today, its ring of city names crowned by the solar system serves as a favorite stage for street artists. Yesterday, it was a theater of politics and diplomacy: in 1983, West German Green Party parliamentarians Petra Kelly, Gert Bastian, and three other MPs demonstrated here for peace, only to be promptly arrested. Six years later, when GDR citizens protested in this same spot, their actions contributed to the fall of the Wall. Few know that a Trabant gearbox powers the world time clock—a testament to GDR engineering ingenuity, making do with limited resources.

The symbolism comes full circle when we consider that "Trabant," before becoming the name of the GDR's official car, means "Satellite."

These structures are not imperial flags planted on distant planets. Through their unique ambition, they have survived different regimes and eras to become symbols of an open world, transcending their original political meaning. When a narrative inspires and carries aesthetic beauty, it transcends its origins to inspire new ones. Similarly, the quest to explore Mars and beyond, if thoughtfully communicated, can unite humanity in common aspirations rather than divide it.

Deep dives

Red Cosmos Cultural history of space fever in the Soviet Union, Julia Richers, 2019 (in German)

Progress Heroine – Valentina Tereshkova, Cosmonaut (PDF, German)

The fascination of space travel in the GDR (Dossier, Public TV MDR, in German)

Yuri Gagarin: The first man in space (Public TV MDR, article in German)

Sigmund Jähn - one of us! The first German in Space (MDR, article in German)

The trail of Sputnik: Cultural-historical expeditions into the cosmic age, 2009 (PDF - German)

RED COSMOS. Space as a place of imagination and longing. Aspects of Soviet astroculture (PDF - German)

Having recently visited Houston, where I lived for several years, I found your Post timely and particularly enjoyed the photographs. Works of space-themed public art seem to be (mostly) cherished, valued and well maintained throughout the former GDR. A couple I find most stunning are “Space, Earth, Man” , a double-sided mosaic by Otto Schutzmeister in Eisenhüttenstadt and “The Man-controlled forces of Nature and Technology”, one of two massive tile murals by Josep Renau, on a multi-storied building in Halle-Neustadt. I expect you are familiar with these works.

I am also fond of a less well-known mural in Eisenhüttenstadt , “The Development of Human Society”. A multi-paneled piece culminating with a mother and child reaching for the stars, by Friedrich Kracht, on an external wall of the former Yuri Gagarin High School. Sadly graffiti is encroaching on the painted tiles and as the school has been vacant for many years, I assume it may be demolished at some time.