"We Were Germans There, Russians Here"

The lesser-known story of Germany's 'Russian Germans', between Catherine the Great, wars and deportations, and remigration to the old German Heimat.

10 MINS READING TIME

Remember those massive anti-far-right demonstrations in German cities recently? They erupted after news revealed about a secret meeting where politicians discussed a potential mass deportation of immigrants who hadn't fully assimilated, including holders of German citizenship.

The far-right, especially the AFD party, has spouted such rhetoric before. But this time, it hit a nerve. People worried they might be deemed "un-German" and face deportation – even if they held German citizenship. And came to the streets.

Among these potentially targeted groups is one most people wouldn't even think of. There are over 2.5 million ethnic Germans who resettled in the Bundesrepublik after the Soviet Union collapsed. These "Russlanddeutschen" or "Spätaussiedler" (late repatriates) spent over 200 years in the Russian Empire and Soviet Republics.

Could these "Russlanddeutsche" be forced to emigrate again? The fear was real enough that an AFD politician, himself of Russian-German descent, felt the need to address it. Eugen Schmidt, an AFD politician who has recently been in the spotlight for having associates with links to the Russian secret service, released a bizarre YouTube video, full of cartoonish language, assuring them that they were real Germans - victims of the other immigrants who came after them.

This isn't just some random YouTube video. It exposes a hidden layer of German identity. Germany is a country of immigration, of course, but also of emigration, remigration and refugees - including millions of Germans. This movement of people back and forth is the real story of Europe, and of Germany in particular. And it's also a big reason why German and Russian history are still so closely intertwined.

So who exactly are these Russlanddeutschen, what is their story, and why have they been back in German headlines for the past two years?

I Want You! wrote Catherine the Great in 1763.

At the heart of this Russian-German story is a German princess turned Russian empress who overthrew her German husband, seized the crown and transformed Russia into a world power. Catherine the Great: an icon symbolising the complex German-Russian cultural, military, economic and migratory ties that have shaped European history.

On 22 July 1763, one year after coming to power, Empress Catherine published a letter inviting foreign settlers to Russia:

"We, Catherine the Second, Empress and Autocrat of all the Prussians of Moscow, Kiev, Vladimir ... authorise all foreigners to come to Our Empire and to settle in all the governorates, wherever it pleases everyone".

This historic document went down in history as the "Invitation Manifesto". Inviting foreigners to Russia was one of her first acts.

Catherine's Invitation Manifesto was a brilliant advertisement to lure settlers. It portrayed Russia as a land of untapped riches - rivers, lakes, "precious ores and metals" waiting to be discovered. Its vision? The "multiplication" of factories and industry. For immigrants, attractive incentives: exemption from military service, self-government, tax breaks, financial aid, 30 hectares per family. Language rights too, especially for Germans. But most seductive of all - "free religious practice".

The strategy was simple - boost population growth and economic development by attracting skilled, loyal foreign workers to tame the "wild country". Although open to all, the main targets were Germans.

And they came.

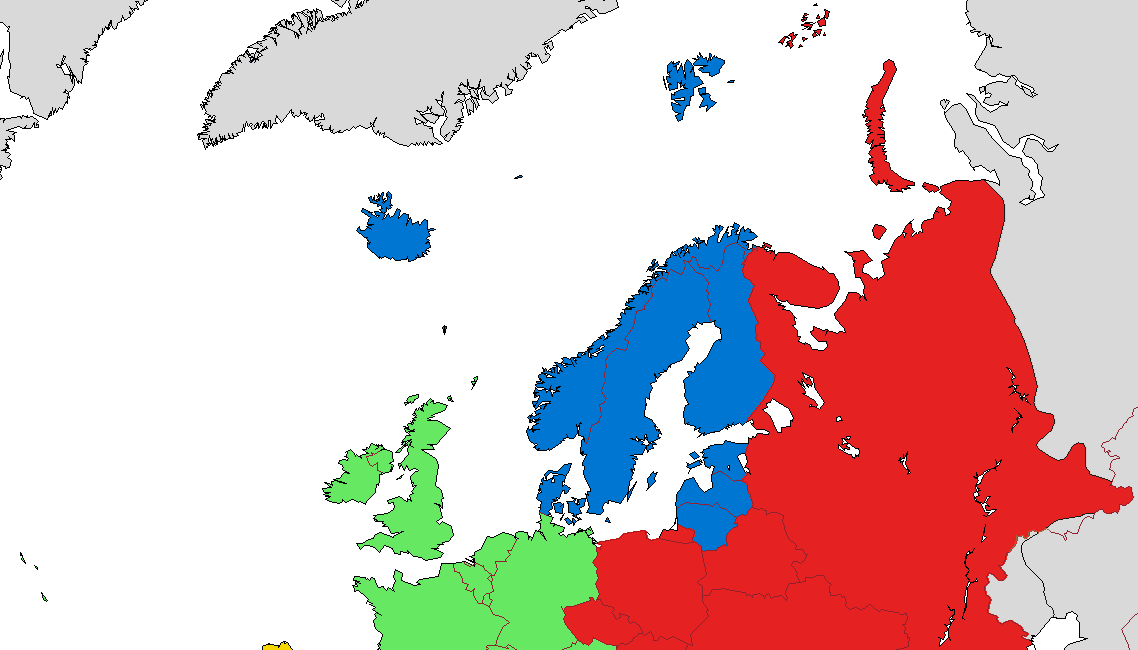

Within 5 years of Catherine's Manifesto, over 30,000 Germans arrived. Religious freedom was the key to attracting those emigrants. They settled all over Russia - around St Petersburg, in the southern regions between the Dniester and Don rivers, in Bessarabia, the Crimea, the Caucasus and along the Volga, where more than 100 villages were founded.

The first wave arrived in poverty, facing food and water shortages, poor conditions and even nomadic raids that killed people. It took a second generation to flourish economically and to establish the first industries on the Black Sea.

The Napoleonic Wars under Tsar Alexander I brought new waves, especially to Ukraine and Bessarabia. Over 3,000 German colonies were established between 1763 and 1862. By the mid-19th century, there were over half a million "Russian Germans" in the Russian Empire.

More mobility, in and out of the Russian Empire.

1871 marked the end of special rights for Russian Germans. Their self-government was abolished. They became subject to general laws under the Ministry of the Interior - henceforth treated as 'Russian citizens'.

With the birth of the German Empire in the 1870s, relations between Germany and Russia soured. German emigrants felt threatened. Some emigrated to North America, Brazil and throughout South America. Some of their descendants still identify with their mixed German-Russian cultural heritage. From the 1890s, settlers pushed also eastwards into Siberia, Kazakhstan and Central Asia, establishing more German villages.

By the late 1800s, nearly 2 million people claimed German as their mother tongue within the Russian Empire. Over 75% were Lutherans. Mennonites, Baptists and Pentecostals formed smaller groups. Their faiths came to Germany with later repatriates in the 1990s.

A quarter of all Russian-Germans lived on the Volga. Another quarter lived in the Black Sea region. About 10% in the Baltic provinces. Dispersed, but holding on to their distinctive identity.

Between war and revolution.

The First World War shattered coexistence. The 2.4 million Russian-Germans were branded "internal enemies" by the Tsar because of their German roots. 300,000 served in the army but were stationed away from the front lines, suspected of collaborating with German soldiers.

As anti-German sentiment spread through Russia, the public use of the German language was banned. After 1915, many Germans near the western border were expropriated and expelled eastwards. Countless died on the way.

The upheaval also sparked anti-German pogroms in the cities. The violence in Moscow in May 1915 was particularly brutal, with many Russian-Germans killed.

But the 1917 revolution offered a chance to regain autonomy under the Soviets. Once in power, the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, granted all Russian peoples freedom, self-determination and the right to form independent states.

The Volga Germans seized this opportunity and in 1918 proclaimed an Autonomous Volga Republic with the right to linguistic, cultural and territorial autonomy. In 1924, this became the official "Volga German ASSR" with German as the state language.

This autonomous republic played an important role in fostering the identity of the German minority - even for those living outside its borders.

Under Stalin.

Joseph Stalin's rise to power in 1928 drastically threatened the German minority. His economic restructuring forced collectivised agriculture and a brutal dekulakisation campaign to eliminate 'kulaks' - wealthy peasants whom communist ideology regarded as exploiters.

Many wealthy German farmers were classified as kulaks, making them prime targets for repression, expropriation and deportation. Forced collectivisation and dekulakisation triggered a famine in 1932-33 that devastated not only Ukraine (the so-called Holodomor) but also the Volga German Republic.

Stalin's parallel campaign against religion struck another blow - undermining a pillar of Russian-German identity. When Hitler came to power in 1933, their position became truly precarious. Nazi propaganda fuelled suspicion by portraying them as potential Soviet spies.

Under the paranoia of Stalin, who saw them as Hitler's 'fifth column' in the making, mass arrests of Russian Germans followed in the 'Great Terror' of 1937-38.

The Second World War.

Hitler's invasion on 22 June 1941 sealed the fate of Russian Germans as "enemies". By Soviet decree, hundreds of thousands were deported to Siberia in a matter of weeks that summer. 35,000 from the Crimea led the way, followed by 400,000 Volga Germans sent to Siberia and Central Asia.

By the end of the year, 600,000-800,000 Russlanddeutsche had been forcibly resettled eastwards from European Russia in the USSR's largest ever ethnic deportation. Many died on the way.

It wasn't over yet. Some 350,000 men and women were next conscripted into labour armies, with over 150,000 working themselves to death.

Rehabilitation, survival, return.

Until 1955, Russian-Germans lived under an extremely restrictive "Kommandantur" mobility regime. A decree in December 1955 lifted some restrictions, allowing them to leave the special settlements where they were confined. However, there was no full rehabilitation - property wasn't returned, nor could they return to their former areas. This led to internal migration, particularly to Central Asia.

It wasn't until the 1970s that larger numbers (around 70,000) were able to emigrate to West Germany as accepted resettlers. But the majority waited for perestroika and the collapse of the Soviet Union. By 1989, 2 million identified themselves as Russian-Germans, although only 48.7% claimed German as their mother tongue.

A 1990 treaty between reunified Germany and the Soviet Union allowed Russian-Germans to retain their national, linguistic and cultural identity. But the momentum was set - some 2.4 million "late repatriates" returned to their "historic homeland" of Germany between 1987 and the present, beginning a long process of reintegration.

Twice foreign.

Resettlement in Germany brought many Russian-Germans a "double foreignness" - summed up as "there we were the Germans, here we're the Russians".

In the Soviet Union, their German names and passport nationalities marked them as distinct, despite their loss of language through deportation. In Germany, however, their Russian language often led to discriminatory labelling as "Russians".

Starting over in the "new old" homeland wasn't easy. Many still spoke 18th-century “Plattdeutsch” German dialect. They remained deeply religious and joined local evangelical congregations. They found it easier to integrate into sports clubs, which they valued from their Soviet schooling.

As "Spätaussiedler" (late repatriates), Russian-Germans received German citizenship, financial aid and language courses. But this support was cut just when it was most needed, with an influx of more than 200,000 newcomers a year in the early 1990s. Initial integration proved difficult.

It took 20 years and a new generation to overcome cultural and linguistic barriers, proudly retaining hybrid Russian-Soviet, Kazakh or Ukrainian-Soviet identities. You'll still find communities celebrating Soviet Victory Day on 9 May - an enduring legacy.

The war in Ukraine and a fragmented identity.

The Russlanddeutsche came back into the spotlight in Germany in 2016, when the migrant crisis and the rise of the AfD made these two and a half million people an important voter base due to their often conservative and identity-focused inclinations.

Broad pro-Russian sentiment, continued use of the Russian language and consumption of Russian media have exposed many Russian-Germans to the spread of Russian propaganda among their communities in Germany, particularly through social media and influencers such as war blogger Alina Lipp.

A 30-year-old Russian-German and former German Green Party activist, Lipp moved to the Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine and now spreads propagandistic reports about both Ukraine and German politics from there.

Suddenly, the old stereotype of being a double foreigner - seen as a German in Russia and a Russian in Germany - resurfaced in all its ambiguity. But the truth is far more complex: it is rare to find a thirty-something of Russian-German descent who sympathises with Putin's regime, unlike many Western Europeans who know very little about Russia or the Soviet Union. Moreover, the fact that the ethnic group called Russian-Germans includes families who have lived and developed in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Tatarstan and the Baltic states reveals a closeness, intermixing and complexity that deserved to be understood earlier, if only to help us better appreciate the world east of the Oder and Danube rivers.

Despite the renewed interest, the Russlanddeutsche remain for most an elusive reality, often confused with Russian-ethnic immigrants in Germany. This reality also intersects with the approximately 200,000 Jewish refugees who arrived in the 1990s from the territories of the former Soviet Union, particularly Ukraine. While this intersection makes everything more fragmented and complex in the face of Putin's war, it also presents an extraordinary opportunity that perhaps only Germany can offer to capture and integrate this complexity.

Go deeper

(English) RUSSIAN-GERMAN HISTORY AS MIGRATION HISTORY, Jannis Panagiotidis, Research Center for the History of Transformations (RECET), 2021

(German) Russian-Germans and other post-socialist migrants, BPB, 2018

(German) (PDF) Grundlinien russlanddeutscher Geschichte, Bayerische Kulturzentrum der Deutschen aus Russland, 2019

(German) Emerged from the Soviet Union, divided by Putin's war? 16.01.2024, WDR

Watch on YT

Eastern Europe: history of an idea.

Where does Eastern Europe begin? Where does it end? According to the EuroVocabulary of the European Union, Eastern Europe comprises the countries of the European continent located east of the current borders of the Union and which were part of the Warsaw Pact, referred to as 'Central and Eastern European countries'. So far, this is the official definitio…