Mourir pour Danzig? Die for Danzig?

The question that divided France in 1939 holds lessons for today.

In the tense months leading up to the Second World War, a single question echoed through the streets of Paris: "Mourir pour Dantzig? - Why should we die for Danzig?” This provocative phrase, scrawled on the front page of a prominent French leftist-liberal newspaper, ignited a firestorm of debate whose echoes have been heard over the past two years in the face of Russia's aggression in Ukraine.

4 May 1939. Europe on the brink, waiting.

Nazi Germany, emboldened by the recent Anschluss of Austria and the concessions made in the Munich Agreement of September 1938, which allowed the Wehrmacht to occupy Bohemia and Moravia in March 1939, now set its sights on Danzig.

Danzig was a predominantly German city incorporated into Poland after World War I. Poland stood firm against these demands, backed by solemn promises of military support from France and Britain, sealed by security agreements signed on 31 March 1939.

These agreements were opposed by larger pacifist sections of the population, although positions were not unanimous: if the majority of the French were in favour of the infamous Munich Agreement, they were also opposed to further concessions to Germany, and 76% declared in 1939 that Danzig would have to be defended by force if necessary.

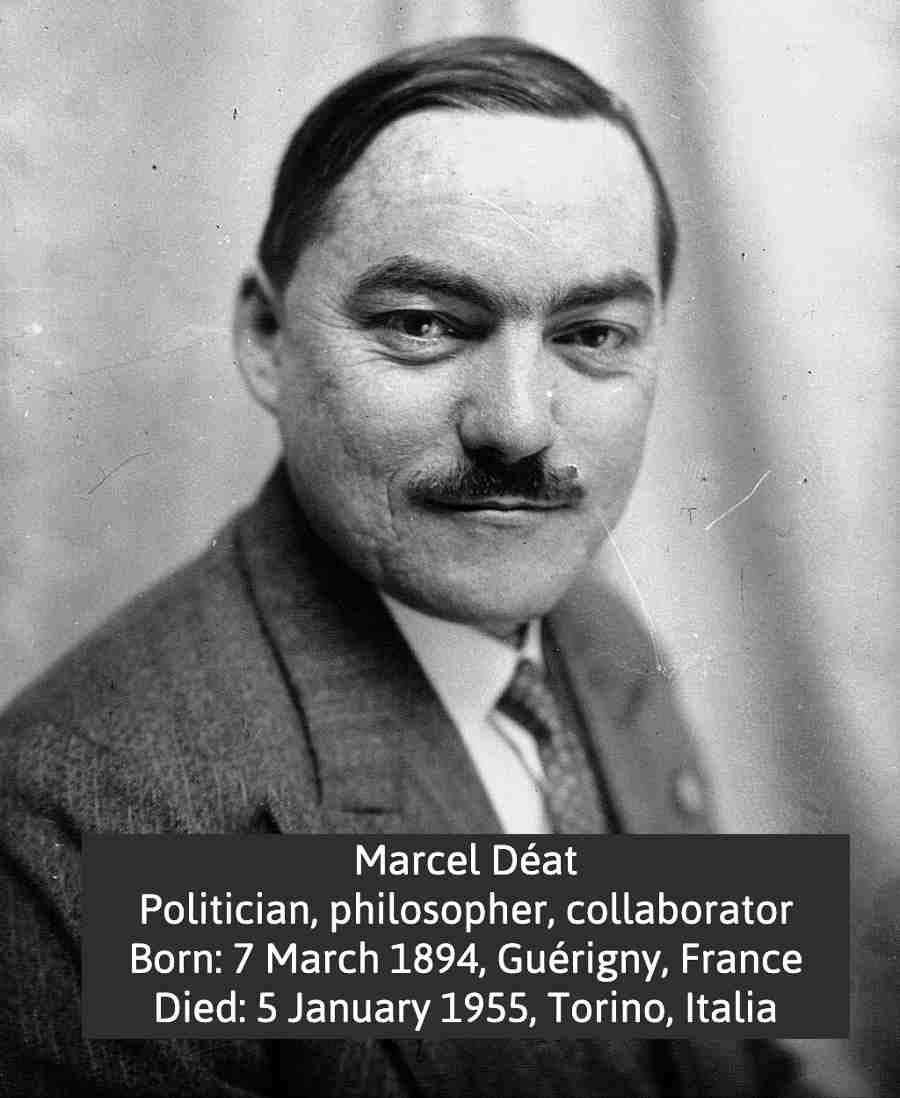

In the midst of this brewing conflict, Marcel Déat, a prominent socialist politician and journalist, wrote a controversial article entitled "Mourir pour Dantzig?”.

Mourir pour Dantzig? Why to die for Danzig?

In the article, Déat challenged the prevailing mood, urging caution and questioning the wisdom of sacrificing French lives for a distant city.

Déat argued that the Polish position, while understandable, bordered on recklessness. He pointed out that Germany already got considerable influence in Danzig, and that surrendering the city wouldn't be synonymous with surrendering the whole of Poland.

"The Nazis have long since become the masters of the city, in which the unfortunate representative of the League of Nations plays only a ghostly role. Under these circumstances, the annexation [of Danzig] to the German Reich is only a formality, unpleasant but by no means catastrophic".

He blamed the Poles for the situation, explaining that a patriotic tremor was running through "this emotional and very sympathetic people".

"They are ready to regard Gdansk as a living space [...] and to reject any dialogue, any discussion with Germany".

In January 2022, Gerhard Schröder addressed the Ukrainians

in a similar vein, accusing them of aggressive rhetoric:

"Ich hoffe sehr, dass man endlich auch das Säbelrasseln in der Ukraine wirklich einstellt" / "I very much hope that the sabre-rattling in Ukraine will finally be stopped". (Source: Der Spiegel, 28.01.2022)

Back to Déat: he argued, the cost of war in human lives was simply too high. Déat believed that diplomacy and negotiation, not bloodshed, offered the only path to lasting peace.

“It is not at all a question of giving in to Hitler's desire for conquest, but I say it very clearly: to drive Europe into war over Danzig is a little excessive, and the French peasants have no desire to die for the Poles.”

Déat concluded:

"To fight alongside our Polish friends, for the common defence of our territories, our goods, our freedoms, is a perspective that can be courageously considered if it is to contribute to the preservation of peace. But to die for Danzig, no!"

Appeasement or selfishness?

The article sent shockwaves through French society. Déat's arguments resonated with some, especially those weary of the scars of the Great War. For many others, however, his words smacked of cowardice and betrayal. Opinion polls showed that a clear majority of French citizens were in favour of honouring their commitments to Poland, even if it meant war.

But Déat's article was not just an isolated opinion piece. It embodied the deeply divisive issue of appeasement that plagued Europe in the late 1930s.

Advocated by leaders such as British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, appeasement advocated concessions to Hitler's demands in the hope of satisfying his territorial ambitions and averting war. Déat, with his question "Mourir pour Dantzig?", became a vocal champion of this approach.

Truth takes time.

The tragic irony, however, is that Déat's own fate became intertwined with the very conflict he sought to avoid. As the war progressed, Déat, leader of the French neo-socialists and a member of parliament, descended into full collaboration with the Nazi regime. He helped to form the last Vichy government. Faced with German defeat, he fled to Italy, where he spent the rest of his life in hiding in 1955. In post-war France, he was sentenced to death.

Truth takes time. This is an old German saying, very similar to the old Jewish principle that the meaning of everything is illuminated by what comes after.

The policy of appeasement advocated by many, including Déat, was less about pacifism and more about selfishness, if not outright sympathy for fascism.

In the face of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, now entering its third year, echoes of "Mourir pour Dantzig?" have resurfaced (“Shall we die for Charkiw?”), prompting us to confront the same tormenting questions:

When is compromise justified? What price are we prepared to pay for peace? And how do we balance the security and the freedom of others with our own? Especially when those others are our fellow Europeans?

The answer may not be definitive, but before we say yes or no, we need to do our homework, look at our European history, its complexities, and listen to its lessons. Peace is not a given. Neither is democracy. Not even the open, prosperous Europe to which we have become accustomed over the past thirty years.

As we navigate today's uncertainties and the sense of fatigue that pervades our European cities (a fatigue that pales in comparison to the daily struggles of Ukrainians fighting for their survival), "Mourir pour Dantzig" serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of inaction, the dangers of appeasement at all costs, and the perennial struggle to balance individual interests with the collective responsibility to preserve international order.

A week of tragic anniversaries.

This is a week of tragic anniversaries. On 22 February 2014, after three months of protests, the Revolution of Dignity succeeded in removing Ukraine's President Yanukovych from office. In Western Europe, these protests are known as the Euromaidan. Yanukovych's forced flight to Russia left a …

A Haunting Silence is Broken: Diving into the Heart of War, "20 Days in Mariupol".

The chilling words "It hurts to see that. And it must hurt", introduce Mstyslav Chernov's documentary "20 Days in Mariupol". In February 2022, just before the brutal Russian bombardment of Mariupol began, Chernov, an Associated Press journalist, arrived with photographer Evgeniy Maloletka and producer Vasilisa Stepanenko. They witnessed the devastating …