Hope is Not a Spectator Sport

Real hope has little to do with optimism, nor with passive waiting: the voices of Vaclav Havel and Pope Francis on what hope is and what it demands.

Remember 2008? Obama's 'Hope' campaign poster captured the vision of people working together to create a better future. The message called on Americans to "choose hope over fear" and see the future as something they could actively shape through positive, collective action. It remains one of the most iconic political images of our time.

MAKING SENSE OF OUR TIMES, ONE WORD AT A TIME

Hope, today?

How remote this idea of hope seems in our world - a world dominated by fear, rejection and resentment. The threats we face seem endless, both globally and personally: war, climate crisis, technological developments with their mix of promise and peril, cruel words and deeds, the erosion of decency and diplomacy, and an aggressive disregard for human dignity - whether of the unemployed, refugees or political opponents.

Yet it is precisely because of these challenges that we realize our profound need for hope. We need it even for the simple act of opening our front-door each day, rather than retreating into isolation and abandoning a vision of the future.

It is no coincidence that Pope Francis has declared 2025 to be the Jubilee Year of Hope. Conscious of how Catholics often associate hope with passive waiting for something distant or in the beyond, he has clearly stated in the papal bull that Christian hope is not to be seen as a "happy ending" to be passively awaited. Rather, it is a promise to be embraced in our present world of suffering, a call to action. The Pope invoked St Augustine's wisdom that hope should make us uncomfortable with what is wrong and give us the courage to change it.

The ambiguous roots of a powerful idea

The Pope's clarification was necessary because the concept of hope has always been - and still is - ambiguous. In Western civilisation, this ambiguity appears in our earliest Greek myths. In Works and Days (Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι), Hesiod tells how Zeus punishes humanity for Prometheus' theft of fire. Zeus sends Pandora, a beautiful but deceitful woman, to seduce Prometheus' brother Epimetheus. She brings a sealed jar as a gift. When Epimetheus welcomes her into his home, Pandora opens the jar and unleashes a myriad of ills upon humanity - epidemics, disease, grief and sorrow... and you can imagine the rest. Only one thing remains inside: Hope, Ἐλπίς, Elpis.

Strangely enough, hope is also counted among these evils, although it is different from the rest. For the Greeks, living under ananke - the inescapable will of the gods, also known as fate - hope (elpis) was merely a blind illusion, since the future always disappoints and is, in any case, arbitrarily decided by the powers above. Yet this illusion helps humans to endure life, making it both an evil and, paradoxically, a good.

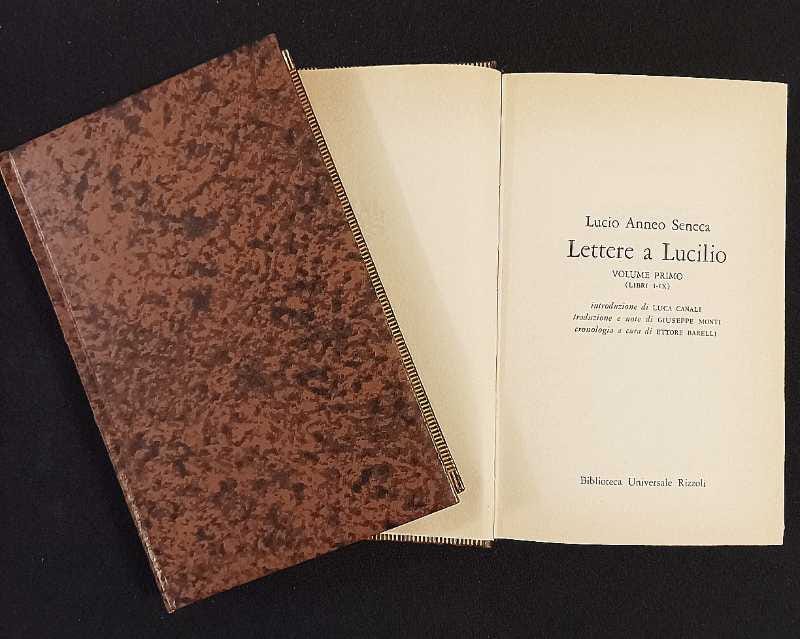

This sceptical view of hope persisted in philosophical Rome before the rise of Christianity. The Stoic philosopher Seneca saw hope and fear as inseparable - two sides of the same coin. He advised the avoidance of both emotions, advocating instead awareness of the present moment and tranquillity of mind. Mindfulness ante litteram.

Though seemingly unconnected, they (hope and fear) are deeply intertwined. Despite their apparent differences, they move together like a prisoner and guard bound by handcuffs. Fear matches hope step for step. Their synchronized movement is no surprise—both arise from a mind suspended in anxiety about the future. Both stem from our tendency to project our thoughts forward rather than staying grounded in the present.

However, with practical sense, when in doubt he advises to prefer hope:

Take a good look at fear and hope, and whenever you are in uncertainty, do yourself a favour: trust in what makes you feel better. Perhaps fear will have more to say; you, however, choose hope.

In contrast to this pessimistic view, Judaism - the other foundational pillar of Western culture - presents hope as a collective force that moves whole peoples towards the future, even when that future seems invisible and distant. Consider the Exodus: the Israelites endured centuries of slavery until Moses emerged with a transformative vision - a free people living in their own land. Despite their scepticism and resistance (the Lord said to Moses, "I have seen this people, and behold, they are a stiff-necked people", Exodus 32:9), he led them through forty years in the desert to a land they could not yet imagine. This story is the essence of hope.

Yet hope continued to be met with scepticism. And why? Because hope, when reduced to passive waiting, rests on the belief that human beings can shape their destiny - an idea that has been severely challenged in modern times.

Spinoza argued that natural necessity governs our lives. Marx claimed that economic interests determined history. Freud argued that unconscious drives shape human behaviour. Neo-Darwinians claim that genetic codes hardwired into our brains control us. Indeed, a thorough review of the psychology, theology and philosophy of hope could fill hundreds of pages.

Optimism or hope?

Meanwhile, the Western world has embraced another concept: the power of individual optimism. It is said that "only optimists get things done". Yet we often mistakenly confuse hope with optimism, as if hope needs a chance of success before we act. But think of the Jews in the desert - did they know the outcome of their journey, which would take more than a generation from beginning to end?

When we subordinate hope to optimism, we act only when we are certain of the outcome. But what happens when that certainty is lacking?

The best answer to this question came from Václav Havel, who became president of Czechoslovakia exactly 35 years ago, on 29 December 1989. He had been the voice of the opposition during socialist rule, especially during the Prague Spring. After enduring years of imprisonment and house arrest for his activism, he eventually led the mass protests that sparked the Velvet Revolution.

In his writings and interviews, he shaped an idea of hope that does not require optimism, and which, more than a perspective, is the motto of a soul and a condition that comes from deep convictions: whether they are religious, political or moral matters little. Hope is a matter of the soul:

The kind of hope I often think about (especially in situations that are particularly hopeless, such as prison) I understand above all as a state of mind, not a state of the world. Either we have hope within us or we don’t; it is a dimension of the soul; it’s not essentially dependent on some particular observation of the world or estimate of the situation. Hope is not prognostication. It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart; it transcends the world that is immediately experienced, and is anchored somewhere beyond its horizons.

Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but, rather, an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed.

The more unpropitious the situation in which we demonstrate hope, the deeper that hope is. Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism.

It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out. In short, I think that the deepest and most important form of hope, the only one that can keep us above water and urge us to good works, and the only true source of the breathtaking dimension of the human spirit and its efforts, is something we get, as it were, from ‘elsewhere.’ It is also this hope, above all, which gives us the strength to live and continually to try new things, even in conditions that seem as hopeless as ours do, here and now.”

And when hope is a deep conviction, it becomes action, not a waiting. As Pope Francis said in his Christmas homily:

The hope that was born that night does not tolerate the indolence of the sedentary and the laziness of those who have settled down in their comfort. (...) It does not accept the false prudence of those who don't want to take a stand for fear of compromising themselves and the calculations of those who think only of themselves; it is incompatible with the quiet life of those who do not raise their voices against evil and the injustices inflicted on the poorest. On the contrary, Christian hope, while inviting us to wait patiently for the kingdom to be born and to grow, requires of us the boldness to anticipate this promise today through our responsibility and our compassion.

With these words, we can move towards 2025 - not with messianic expectations of pacifying leaders, but with the conviction that each of us has both the duty to hope for the future and the responsibility to shape it.

As we say in Austria,

Einen guten Rutsch ins neue Jahr!

THIS POST IS DEDICATED TO A HERO OF DEMOCRACY

Václav Havel is elected president in Prague (DEU) 29. Dezember 2024