Homelands: a personal history of Europe, by Timothy Garton Ash.

Choosing Europe: Timothy Garton Ash's emotional and political journey through the continent's memory, identity and a new chapter to write.

“To write a real, true history of the Europe of our century, that would be a goal for a lifetime.” Leo N. Tolstoi, Diaries, 1852

Can a history of Europe be written? Is there only one European history? Or are there as many as there are Europeans?

Timothy Garton Ash's European narrative begins here, with the understanding that a European identity - and thus the story each person can tell of Europe - is inherently singular and personal.

Ash, for instance, is quintessentially English. Yet, by cultural choice, he identifies not only as a European, but as a Central European. European identity, he argues, is an emotional matter and a choice, perhaps more significant than genetic heritage:

"As if a genetic explanation were needed for feeling emotionally connected to another part of Europe. Our identities are given, but also made. We can't choose our parents, but we can decide who we become."

"Basically, I am Chinese," wrote Franz Kafka in a postcard to his fiancée. When I say that I am basically a Central European, I don't mean that I am literally descended from the Central European Jewish writer Sholom Asch, but rather I postulate an elective affinity.”

This also means that any account of European history is by definition individual and personal.

“So if there are about 850 million Europeans today - using a broad geographical definition of Europe that also includes Russia, Turkey, and the Caucasus - then there are also 850 million individual Europes. Tell me your Europe, and I'll tell you who you are.

It is from here that Garton Ash's narrative begins, in more than four hundred pages and five chapters: a personal history of Europe that, in his case, combines collective facts and autobiography, individual destinies and high politics.

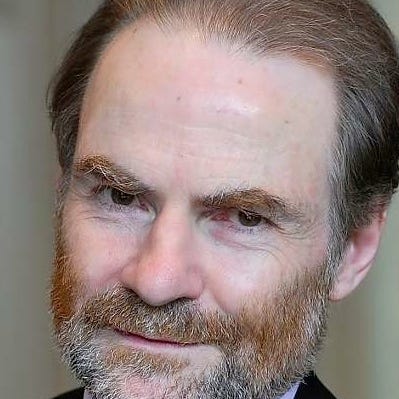

Timothy Garton Ash

Timothy Garton Ash, author of eleven books on contemporary European history, has chronicled the continent's transformation over the past half-century. He serves as Professor of European Studies at the University of Oxford and Senior Fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution. A regular contributor to international newspapers and magazines, Garton Ash is also one of the most authoritative voices on Substack.

In "Europe: A Personal History" (originally titled "Homelands" in English), he recounts Europe's recovery from the devastation of war, its rebuilding, and its journey towards the ideal of an "undivided, free and peaceful" continent—until Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

The book's impetus is, unsurprisingly, concern over a seemingly broken "memory engine" in Europe, following two decades of relative freedom and prosperity. No country has joined the European Union since 2013; Britons voted to leave the bloc; war and the rise of autocratic figures like Hungary's Viktor Orbán have threatened the EU's eastern flank, where Vladimir Putin's war could become a defining moment for the continent's future.

The book charts the major phases of European history, divided into chapters: "Destroyed" (1945), "Divided" (1961-1979), "Emerging" (1980-1989), "Triumphant" (1990-2007), and "Reeling" (2008-2022).

The End of Nazism, the Beginning of a New Europe? Normandy.

Timothy Garton Ash's father was among the first-wave soldiers landing in Normandy on D-Day's early morning. The historian traces his father's journey as an officer through France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, recounting meetings with contemporary witnesses.

The book's first chapter, "Destroyed: 1945," reveals a staggering statistic: between 1939 and 1948, nearly ninety million Europeans—one in six—were killed or displaced.

We often consider 1945 Europe's "year zero," but the war's end and the "after" varied by location.

For those beyond the Iron Curtain, 1945 differed from Western Europe's experience. Moreover, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Turkey didn't embrace democracy post-World War II. Looking ahead, Garton Ash notes,

The end of the war in Ukraine will be a new "year zero" for Europe.

Garton Ash's personal European journey began in 1973 when he visited France as an 18-year-old exchange student. In 1975, he first ventured beyond the Iron Curtain, embarking on a five-year history study. He divided his time between Oxford and West Berlin, even becoming a guest student at East Berlin's Humboldt University. Decades later, he discovered traces of his adventures in the extensive files the Ministry for State Security had kept on him.

Solidarność

It was an eye-opening experience for the historian, who met his future wife Danuta, witnessed the birth of Solidarność (Solidarity) in August 1980 and became friends with many of the leading figures in the Polish opposition.

Among them was Bronislaw Geremek, a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto and a prominent figure in the Solidarność movement, who would later, as Polish foreign minister, sign the agreement for Poland's accession to NATO in 2004.

Another is Cardinal Karol Wojtyła. Like many others, they were united by the conviction that Communist rule in Poland was about to end and that the Eastern Bloc would eventually collapse. Wojtyła expressed this vision to Garton Ash in the striking words that "the kingdom of Satan must fall".

What happened in Poland in 1980 was the "first breach" in the wall and, for many outsiders, an unforeseeable miracle: in the entire sixteen months from the start of the Gdansk strike led by the electrician Lech Wałęsa to the imposition of martial law on 13 December 1981, no one was killed. A quarter of a century later, Bronisław Geremek proudly claimed that "Solidarity was the largest non-violent movement for change in European history". After sixteen months of freedom, everyone agreed that Poland had become a different country, a country where a "revolution of the soul" had taken place.

All of this came as a surprise to Western audiences: for them, there was only darkness and silence behind the Iron Curtain. The truth was very different: the East into which young Garton Ash ventured was rich in ideas, culture and conversation. It is a sphere where, as the poet Paul Celan said of his home town of Czernowitz before the Holocaust, "people and books lived".

Garton Ash recalls the days he spent talking to his hosts in the basements, kitchens and catacombs of the opposition:

“Religion still played a role. In the living room, people made music around the piano, as in 19th-century novels. There was time and space for friendship. The West may have been richer in money, but the East seemed richer in time. Conversations here had a special intensity. I returned to the West with the impression that the American writer Philip Roth so wonderfully summed up with his bon mot: "I work in a society where everything is permitted for a writer and nothing matters, while for the Czech writers I met in Prague, nothing is permitted and everything matters.”

After these encounters, he was convinced that a peaceful revolution was imminent throughout the Eastern Bloc. He was right.

1989: Between Joy and Illusions

Those who witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall may feel nostalgic as they read the chapter "Emerging", which describes the events leading up to 1989. That year was truly extraordinary: several factors converged to end the Cold War in Europe, none of them inevitable. The 1980s had seen stagnant European integration, forests dying from acid rain (Europe's first major environmental crisis) and public discourse dominated by fears of nuclear war.

On 31 December 1980, Garton Ash wrote in his diary:

"WE WILL SEE NUCLEAR WAR IN THIS DECADE".

In this context, Garton Ash argues that individuals made the difference: Margaret Thatcher, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and US President Ronald Reagan, certainly, but also German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and European Commission President Jacques Delors. Leaders began to trust each other, and leadership changes proved to be fortuitous - Gorbachev's role in the events of 1989 is undeniable. These leaders not only trusted each other, they also won the trust of their people. Gorbachev, for example, was deeply moved by his enthusiastic reception in West Germany in the spring of 1989, especially by the steelworkers in Dortmund. Their chants of "Gorbi, Gorbi" gave rise to the neologism "Gorbimania".

Garton Ash devotes several pages to Hungary, one of the countries that played a key role in 1989 and subsequently took an illiberal political turn that surprised many and continues to preoccupy us today.

In particular, Garton Ash recalls some key moments: in early May 1989, Hungary began dismantling electronic surveillance equipment and barbed wire along its western border. Images of the fences between Hungary and Austria being torn down were broadcast around the world, prompting thousands of East Germans to travel to Hungary. Many sought refuge in the West German embassy in Budapest, while others waited near the border for an opportunity to escape.

Then, on 16 June 1989, a highly symbolic event took place: the reburial of Imre Nagy, the reformist Communist leader of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Garton Ash tells the story:

In my notebook, I recorded the extraordinary scene of the black-clad mourners on Heroes' Square in Budapest and the electrifying speech of a then-unknown young man named Viktor Orbán, who, contrary to an informal agreement among opposition speakers not to be too provocative, demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops. In Hungary, as in Poland, a kind of negotiated transition followed, which I called "Refolution," a mixture of reform and revolution.

Ten days later, in front of the world's cameras, the foreign ministers of Hungary, Gyula Horn, and Austria, Alois Mock, went to the Austrian-Hungarian border to cut through a section of barbed wire that had divided their countries for decades. It was part of a process that had seen Hungary quietly leave the Warsaw Pact for years. But neither Hungary's allies nor NATO countries took these signals seriously.

The Pan-European Picnic followed on 19 August 1989 - a peace demonstration on the Austrian border near Sopron. The idea came from Ferenc Mészáros of the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) and Otto von Habsburg, then president of the Pan-European Union. They took it to Miklós Németh, the Hungarian prime minister, and together they set in motion a chain of events whose acceleration is difficult to describe. As Garton Ash writes:

Less than a week later, the East Germans who took part in a "Pan-European Picnic" near Sopron were able to flee en masse without being stopped. A few days later, the Hungarian leadership met secretly with Helmut Kohl and his astute Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher at Gymnich Castle near Bonn. In a dramatic conversation, the Hungarians declared themselves ready to terminate their agreement with the comrades in East Berlin and to allow East Germans (…) to go to the West unhindered. In return, the heavily indebted Hungarian state received a loan of 500 million Deutschmarks and the promise to support its desire to join the European Community. With clever timing, Hungary had switched sides…

“Triumphant“ (1990-2007)

The walls fall and wars begin again. Europe, a continent of peace?

Even after 1945, Europe was far from being a continent of peace. Today, many are shocked by Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, but the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s were just as horrific.

Garton Ash vividly describes the collapse of Yugoslavia - a multi-ethnic state - into genocidal war, which reached its nadir with the Srebrenica massacre in July 1995. As a journalist and historian, he travelled extensively, reporting from Sarajevo, Zagreb, Belgrade, Pristina and many other places caught up in the bloody turmoil.

Once again, Western Europe seemed paralysed. It wasn't until 1999, when Milosevic's attacks on the Kosovo Albanians threatened to escalate into genocide, that the West finally intervened. This came after prominent figures such as the Pope and Vaclav Havel warned against a repeat of Bosnia. The intervention was ultimately led by the United States.

In these pages, Garton Ash also takes the opportunity to remind us that Bill Clinton was the last US president to have a deep knowledge of and genuine affection for Europe:

“This continental drift was masked in the 1990s by the enthusiasm for Europe of President Bill Clinton and his colleagues, who spent a lot of time on the post-Wall issues of Russia, Germany, NATO enlargement and the former Yugoslavia. Moreover, they were personally shaped by European experiences. Clinton's Secretary of State Madeleine Albright was in fact a European, born in Prague. The last section of the report by American diplomat Richard Holbrooke on his energetic peace efforts in Bosnia is entitled "America, still a European power." Clinton himself had studied at Oxford (…) and once declared: "Since Europe is as much an idea as a place, America is also a part of Europe.””

Later, the chasm between Europe and the US became clear: On Saturday 15 February 2003, millions of Europeans took to the streets in London, Madrid, Rome and other European capitals to protest against the invasion of Iraq. The French and German governments listened to their people and decided not to join the invasion of Iraq. We are now experiencing the long-term consequences of the Middle East policy of the 2000s.

Is social injustice and corruption the price of freedom?

For the peaceful revolutionaries of 1989, the real challenge began after victory. The history of post-war Europe wasn't a simple story of virtuous heroes creating a utopia. The tasks were immense, and many succumbed to the temptations of power. Unbridled capitalism brought new challenges, which Garton Ash witnessed at first hand in Central Eastern Europe.

In Poland, market-liberal shock therapy loomed. While there were many theories about the transition to communism, there was no blueprint for its dismantling. In the Czech Republic, Václav Havel - opposition hero, new president and friend of Garton Ash - suffered bitter defeats. Romania and Bulgaria, future EU members, struggled with corruption and their communist legacies.

The period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the financial crisis saw both progress and disillusionment. As Central and Eastern European countries prepared to join NATO and the EU, their quest for "liberty, fraternity, normality" sparked a massive experiment. Often implemented through shock waves, this simultaneous creation of liberal democracy and capitalist economies produced mixed results. The roots of the success of populist parties and the rise of a new oligarchic class in Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia can be traced to the shortcomings of this transition.

Europe without a soul

Meanwhile, the European project advanced: the Maastricht Treaty transformed the European Community into a Union in 1992; monetary union - almost imposed by France on a reluctant German Chancellor Helmut Kohl - was completed with the introduction of the euro in 2002; then came the great EU enlargement to the east in 2004, racing against the risk of losing the "new" European countries to the influence of other superpowers; finally, a growing system of federal institutions with increased powers emerged. But all this tended to happen with less emotion, and less to inspire. Garton Ash quotes Vaclav Havel to illustrate the lack of sentimental resonance in post-Wall Europe.

Addressing the European Parliament in 1994, Vaclav Havel likened reading the Maastricht Treaty to "looking at the instruction manual for an absolutely perfect and incredibly ingenious modern machine". Maastricht had "appealed to my mind, but not my heart".

Havel argued that the EU required

"its own charter, in which the ideas on which it is founded and the values it wants to embody are clearly defined".

Five years on, speaking before the French Senate in 1999, Havel acknowledged the strides made in European unification, yet cautioned:

“I cannot help feeling that the whole thing is like a train journey that started earlier, at a different time and under different circumstances, and that simply continues without getting new energy, new intellectual impulses, a renewed sense of the direction and the goal of the journey.”

February 2000 he returned to his idea of the charter in front of the Europan Parliament in Strasbourg. He now called it a European constitution, but it should be "a constitution that every child in Europe can easily learn at school":

I believe that the European Union should, sooner or later, have a clear, accurate, universally understandable constitution: a constitution which every child in Europe can simply learn at school. This constitution would comprise two parts, as is standard practice. The first part would set out the fundamental rights and duties of the European citizens and states, the fundamental values on which a united Europe is based and the sense and purpose of the European structure. The second would describe the main institutions of the European Union, their main powers and the relations between them. The fact of having a constitution would not automatically radically transform the union of states as we know it into the federal superstate which the eurosceptics dread; it would simply give the people of the Europe under construction a clearer idea of the nature of the European Union, thereby allowing them to understand it better and identify with it. (Source: 12. Address by Mr Vaclav Havel, President of the Czech Republic, Verbatim, 16 February 2000 - Strasbourg)

Reeling (2008-2022)

The final chapter stands in the shadow of Putin's Russia and the rise of populism across Europe.

It was at a conference in St Petersburg in March 1994 that Garton Ash first met Vladimir Putin, who declared that certain territories outside the Russian Federation had "historically always belonged to Russia", mentioning Crimea in particular. However, Putin had to wait until he came to power to implement this vision. In December 1994, the Budapest Memorandum stipulated that Ukraine would give up its large nuclear arsenal in exchange for the Russian Federation's promise to respect the country's territorial integrity. This commitment was reaffirmed in 1997 by a bilateral Treaty of Friendship with Ukraine.

At a press conference in Rome in May 2002, following the inaugural meeting of the new NATO-Russia Council, Putin stood beside the NATO Secretary General and declared:

"Ukraine is an independent, sovereign nation-state and will choose its own path to peace and security".

Just twelve years later, in 2014, Putin stood before an ecstatic audience in the Kremlin to celebrate Russia's annexation of Crimea. In the same period, 2014-2015, anti-liberal populists began to score victories across Europe. The following year saw Brexit.

The end of eras and the beginning of another.

Ash references Stefan Zweig's "The World of Yesterday" and ponders the sudden surge of interest in the Austrian writer's book a few years ago, particularly in English-speaking countries.

As we entered the second decade of the 21st century, there was suddenly a lot of talk about a book by the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig titled The World of Yesterday. The memoir, subtitled "Recollections of a European," which he wrote in exile during the Second World War, is an elegiac evocation of a Europe - "the true homeland that my heart has chosen" - that Zweig considers lost forever.

Garton Ash quotes the writer Daniel Kehlmann, who says that the current popularity of S. Zweig's book "speaks volumes about our times, our fears and our sense that something may be coming to an irrevocable end".

The war in Ukraine marks the end of both the post-Wall and post-war eras, bringing us back to a place we naively thought we would never visit again:

After Vladimir Putin's troops marched into Ukraine on Thursday, February 24, 2022, Europe went all the way back. On the ground where the Wehrmacht and SS had waged a war of terror between 1941 and 1944, a war of terror was now being waged by Russian forces: indiscriminate shelling of cities, torture and execution of civilians, rape. The same cities, villages and communities, the same people, sometimes even the same men and women were affected again.

Once again, millions of innocent men, women and children had to flee their homes with "nothing but three suitcases".

What is this post-Cold War Europe? And where must it find its new balance? In a world that is no longer bipolar:

…the world surrounding Europpe is a world of realpolitik, where war is once again a political tool, and where there is no clear bipolar structure, but rather several major middle powers. It is a world of "à la carte" alliances, where countries like India, Turkey, Brazil, or South Africa feel no compulsion to ally themselves with the West or the East, with us or China, with us or Russia. They are quite content with their multiple partnerships. It is completely different. And I believe we Europeans can only adapt to this with great difficulty.

Is there hope for Europe?

Yes, argues Arton Gash, but only if Europe continues to fulfil its mission and follows the path of more freedom, not less.

"For 'my Europe' was - and still is - a struggle for freedom. Where the cause of Europe went hand in hand with that of freedom, I was happiest; where Europe seemed to come into conflict with freedom, or at least appeared indifferent to it, I was most dismayed. Freedom, which can never be fully achieved, means much more than the absence of dictatorship. But as a first step, one must rid oneself of one's dictatorship, as the Spanish, Portuguese, and Greeks had recently done."

Ukrainians are writing an extraordinary new chapter in European history with their will to freedom, expressed in the beautiful word 'volya', which means both 'will' and 'freedom'.

(…) Tetiana, a student from near the Belarusian border, works part-time as a tattoo artist. She tells me that one of the most popular tattoos now is the word "volya," which means both "will" and "freedom." When she traveled abroad before the war, "foreigners thought Ukraine was part of Russia," but now "the world is finally learning what Ukraine is."

From here, Europe shall restart.