Banning symbols, fighting ideas. Where do we stand in Germany and Italy in 2024?

A few things to know about banned symbols and signs in Germany: what the law says, how it is applied, and why German meticulousness is useless when the political substance gets out of control.

A video from Italy has been circulating on social media over the past week: it comes from a commemoration held every year by neo-fascists in Rome and, as every year, it shows hundreds of arms raised in the fascist salute.

The political and media response has been huge in Italy, but far less so outside the country - minor news in the complicated world we live in. All in all, not even surprising:

There is no international tourist in Italy who has not at least once seen calendars with Mussolini's face being sold in front of the Trevi Fountain, arms raised unnoticed, and at the tomb of the Italian dictator, which is visited every year by supporters with flowers and wreaths.

Only in Russia have these images had a certain echo, but there - you know - every opportunity is good to say that the fascists are us, not them.

The only notable thing in this round was the Italian attempt to trivialise the fascist salute by saying, more or less, that 'you see Nazi salutes every day in Germany anyway'.

But is it really so?

Before going into detail, the dry answer: 'You can't walk around Germany with your arm raised in the Nazi salute. Nope. No way. It is a punishable offence. Full stop.'

The only time I saw someone raise his arm in Berlin, two policemen took him away, partly to protect him from the crowd.

More recently, in September 2023, I remember that two Italians who climbed on a table at the Oktoberfest to give the Nazi salute were immediately taken to a police barracks and from there to a judge who issued a custody order for the two, who were charged with committing a crime relevant to state security (see pr. 1678 - Staatsschutzrelevante Delikte - Bayerische Polizei).

The corollary to the short answer might be cultural: here the gesture of the Nazi salute is in fact taken seriously, both by those who would never do it and by those who do.

I mean, that's it?

The longer answer: Germany's laws and how they are applied.

Both Germany and Austria have enacted very strict rules against the symbols of their Nazi past, also in the knowledge that what cannot be eradicated must at least be contained. Why the Italian case is still so different is one of the inexplicable things about the post-war history of the former Italian ally.

What are these rules? How do they differ from Italian legislation and how are they applied on a day-to-day basis?

The German Penal Code has two reference articles concerning propaganda by unconstitutional organisations and the use of their symbols: Section 86 regulates the distribution of propaganda material of unconstitutional and terrorist organisations; Section 86a deals specifically with the use of symbols. This is the text, translated:

86a. Use of symbols of unconstitutional and terrorist organisations.

Whoever disseminates the symbols of one of the political parties or organisations designated in section 86 (…) in Germany or uses them publicly, in a meeting or in content disseminated by themselves or produces, stocks, imports or exports content which depicts or contains such a symbol for dissemination or use in Germany or abroad (…) incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or a fine.

Symbols are, in particular, flags, insignia, uniforms and their parts, slogans and forms of greeting. Symbols which are so similar as to be mistaken for those referred to in (the previous) sentence are deemed to be equivalent to them.

It is interesting, but not historically surprising, that both the Italian Law “Scelba” - which prohibits apology for fascism - and these (West)-German sections were introduced in the same years, between 1952 and ´53.

Both the German 86 and 86a sections have been amended several times, until very recently, to extend the scope to all banned political and terrorist organisations, including those from abroad (e.g. the Kurdish PKK), and to better reflect the evolution of media and distribution technology.

This breadth of coverage, acquired over time, is already the first major difference from the Italian law.

Italian vs. German law: the most striking differences.

The question of using fascist symbols in Italian law is linked to the so-called "Apology for Fascism", which is defined as follows:

(English translation, original Italian version here) "when an association, a movement or, in any case, a group of not less than five persons pursues anti-democratic aims specific to the fascist party, by glorifying, threatening or using violence as a method of political struggle or advocating the suppression of the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution or denigrating democracy, its institutions and the values of the Resistance, or carrying out racist propaganda, or turns its activity to glorifying exponents, principles, facts and methods specific to the aforementioned party or carries out external manifestations of a fascist nature." (A short, well-done Italian explainer —> here)

#1 The scope.

The first fundamental difference is the breadth: from revision to revision, the German law has become 'all-encompassing' of any anti-democratic organisation.

Article 86a is constantly updated, based on the progressive banning of anti-democratic and/or terrorist organisations of various kinds: extreme right, extreme left, anarchist, terrorist and extremist organisations from abroad.

As of mid-January 2024, 74 organisations considered anti-democratic are banned in Germany. Of these, 58 are right-wing extremist, 10 are left-wing extremist, 5 are Islamist extremist and 1 is a criminal organisation.

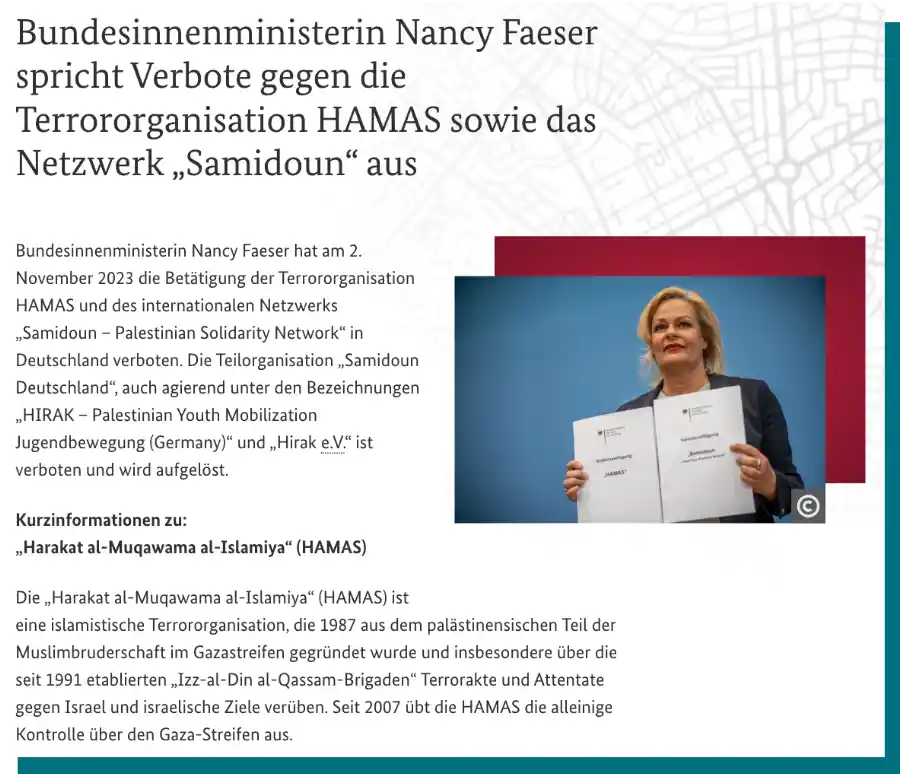

The most recent terrorist organisations to be outlawed are 'Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiya' (i.e. HAMAS) and 'Samidoun - Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network'. Both have been declared illegal as of 2 November 2023:

#2 The intent.

Under German law, the intention with which a symbol, an acronym, a gesture or a uniform is worn is almost irrelevant.

To be clear: a Nazi uniform worn as part of a historical re-enactment, along with other uniforms, is not punishable - however, the re-enactment must be announced and approved by the relevant local authorities, so it falls under a so-called social appropriateness clause (Sozialadäquanz-Klausel) -. But if you walk through the centre of Mainz at Carnival dressed as a Nazi officer, then you are committing an offence. Not socially acceptable, okay?

So the explanation: “Section 86a StGB criminalises the "dissemination" and "use" of the above-mentioned signs. (…) According to case law, “use” in this sense is any use that makes the sign visually or acoustically perceptible - even if only partially - irrespective of the intention or disposition of the person acting. In principle, this also includes a one-off, joking or "critical" use of the trade mark, such as the ironic display of the Hitler salute to the police.”

(Source: Das strafbare Verwenden von Kennzeichen verfassungswidriger und terroristischer Organisationen § 86a StGB im Spiegel der Rechtsprechung, Bundestag, © 2021 Deutscher Bundestag)

Further example: the use of Hitler portraits together with images of Obersalzberg on tourist postcards is also prohibited. The same is probably true for the merely provocative or thoughtless (German: gedankenlos) use of symbols.

“Thoughtless” de facto invites to think twice before sketching some swastikas here and there.

Wait a minute! But what about the use of Nazi symbols for anti-fascist purposes?

Despite the fundamental irrelevance of the motivation of the actor, there are exceptions. This is particularly the case if the use of the symbol clearly and unambiguously expresses opposition to the organisation in question and the fight against its ideology.

According to the German Federal Court of Justice, a crossed-out swastika, which is widely used as an expression of opposition to right-wing extremist content, is therefore not covered. But: some jurists still disagree on this point.

Very broad, constantly updated and enciclopedic: the hard life of those called to control the application of Section 86a.

The ancient Greek word ἀκριβής (akribḗs) means 'exact, accurate, precise'. The only modern language that has systematically adopted this word (though mostly in academic and magazine cultural pages) is German, where the adjective "akribisch" means more or less the most possible - and painful - level of precision and meticulousness you can use.

It is the perfect word to describe the painful classification work done and iterated on symbols, signs, even phrases, sentences and acronyms that must be observed in order to apply the prohibitions laid down in Section 86s.

It all starts with the rich symbolism of the Nazi era and its far-right heirs: the manual (here) listing all the illegal symbols and gestures is 86 pages long!

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesamt für den Verfassungsschutz) is responsible for maintaining this brochure.

Its application is the task of the federal and local police corps. That means: at every public gathering, including rock concerts, demonstrations, public places such as gyms and saunas, beaches, concert halls and, last but not least, social media and messaging groups.

Imagine such a right-wing music festival taking place in the summer: the checks carried out by the police at these gatherings include tattoos, which must be covered to avoid public display, T-shirts, slogans and acronyms (and suspicious numbers, see below), even the lyrics of songs or slogans shouted by the crowd.

Here are a few examples to illustrate the complexity of the matter and - perhaps - its excesses:

The world of runes and skulls is always well represented at outdoor rock festivals. But when are runes and skulls legitimate, and when are they not? While some symbols are clearly "Nazi", others are not. Someone has to decide on a case-by-case basis what should be removed and what should not.

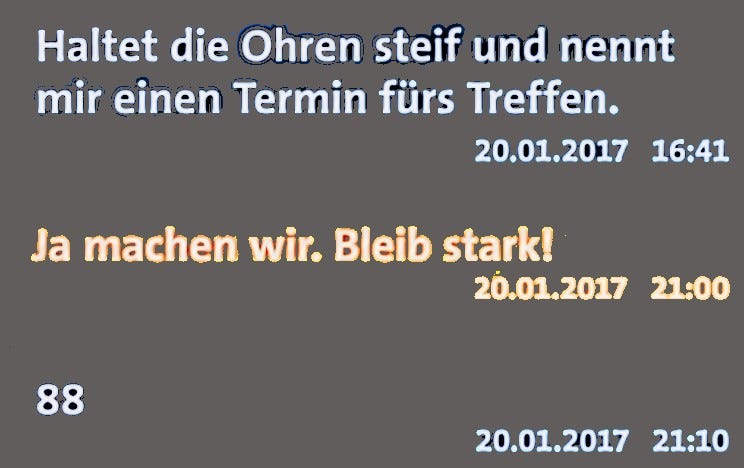

What about the numbers? The most notorious combinations are 18 and 88. 1 stands for the first letter of the alphabet (A), 8 for the eighth letter (H). 18 = Adolf H. 88 = Heil, etc. More recently, the number 14 has been imported from the USA: it stands for "14 Words", the white supremacist slogan consisting of 14 words: "We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children". Interestingly, the racist organisation that came up with the 14 words has as its goal "the overthrow of the Zionist occupation government in Washington" (yes, some US left-wing activists may be surprised by this, but white supremacists do not like Sionists: they never stayed in the same front). A more sophisticated number is 28 (the second and eighth letters of the alphabet), used as a substitute for the abbreviation "B & H" of the organisation "Blood & Honour". Police officers in Germany know these numbers by heart: unfortunately, some of them even use them in their own chats... and that, so to say, speaks for the (huge) problem we have in Germany,

Closing of mails. In letters and emails intended to reach a large or potentially large group of people, it is also forbidden to use the salutation “„Mit deutschem Gruß“ ("with German greetings") if "the external presentation and content clearly indicate that this is meant in National Socialist parlance".

Flags. In an age of total access to information and, at the same time, gross ignorance of the most recent history, it is not so easy to understand which flags can be used and which cannot. The case of the flag of the German Empire (Reichskriegsflagge) is remarkable: in general, the war flag of the German Empire does not constitute a criminal offence. Nevertheless, it may be confiscated in specific individual cases if this is needed to avert specific threats to public safety at public demonstrations. However, the use and distribution of the Reichskriegsflag´s version used by the National Socialists from 1935 to 1945 is always punishable. So pay attention to the details!

Words and verses. To give just a few examples, the use of the slogan "Alles für Deutschland" (Everything for Germany) in the context of a speech at a meeting is also punishable: this was the slogan of the SA. The same applies to the phrase "Deutschland erwacht" (“Germany awake”) which was also used by the SA. The SS slogan "Meine Ehre heißt Treue" (My honour means loyalty) and the H. Jugend slogan "Blut und Ehre" (“Blood and honour”) are also included. There is also a large collection of lyrics from Nazi songs in the banned catalogue, but one wonders: how many people really know these songs? Isn't such precision a waste?

On the brink of ridicule? The case of Pepe the Frog.

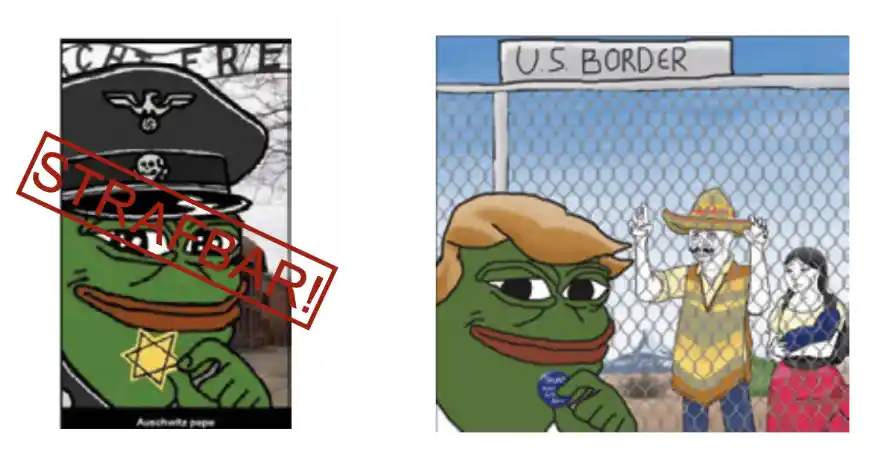

The Pepe the Frog meme has been circulating for years, but in 2016 it enjoyed a kind of resurgence in popularity. The original meme, banned in Germany, shows the human-like frog figure wearing an SS cap in front of the entrance gate to the Auschwitz death camp. Pepe looks directly at the user, smiles cynically and holds a Jewish star between his thumb and forefinger.

These memes were taken up and varied on forums by right-wing extremists who saw Donald Trump as their candidate for US president in 2016. Pepe's pose and facial expression remained the same; instead of the SS cap, the frog was drawn with Donald Trump's hair; instead of the Jewish star, he now holds a Republican Party campaign pin. The Auschwitz background has been replaced by a drawing of the border fence between the US and Mexico.

Between censorship, freedom of expression and a jungle of new threats. Should we fight symbols or ideas?

If this acrimonious classification of signs and symbols is tedious, but all in all manageable (at least with reference to Nazism and the extreme right), never before has a forest of symbols and phrases inciting hatred appeared on German streets of the size we are seeing today.

Hamas, Isis (which never disappeared), but also phrases taken from the Koran and used as emblems of the future Islamic State of Europe, even songs in Swedish calling for the destruction of the State of Israel (heard on the streets of Berlin a few weeks ago): this jungle of hatred, this proliferation of acronyms and clubs and new groups formed directly on the Internet, without even needing to manifest themselves on the streets, shows all the limits of the rigid control that the German authorities are still trying to exercise.

When is a flag acceptable and when is it not? What happens when everyone accuses everyone else of being "the real Nazis" (by the way, the Russian symbol of the invasion of Ukraine, the "Z", has also been banned in Germany)?

And what are the limits of freedom of expression?

In Italy, the rule of law has gradually taken on a libertarian orientation. It even sees a certain legitimacy in the historical praise of 'the statesman Mussolini'.

In Germany, also the product of a political (and religious) philosophy that sees a direct link between words and deeds, a more rigid orientation has prevailed.

And yet, this symbolic and linguistic rigour, not coupled with a real civic education, a sharing of principles, only serves to a certain extent.

The last months of 2023 and these first days of 2024 have been a rude awakening for Germany:

On the one hand (see also the case of Masha Gessen, as well as the new explosion of anti-Semitic feelings), the culture of remembrance (Erinnerungskultur) of which the country was proud is proving to be as fragile as a house of cards;

On the other hand, the case of the AFD - now the second largest party in Germany according to the polls - is prompting debates, probably out of time, on the possibility of banning the party, as was tried unsuccessfully against the NPD a few years ago;

Then there is the increasing number of cases of groups of police officers (and to a lesser extent also among the military) with pro-Nazi sympathies, which have become recurrent news in the chronicles of each of Germany's sixteen Länder;

Finally, the now explosive problem of parallel communities in which the most extreme forms of Islamism are no longer hidden, and which threatens to drag the whole of German society into a conflict of unprecedented proportions.

The effort to control the expression of anti-democratic sentiments, though justified, necessary and undertaken with seriousness, contrary to what some Italian opinion-makers would like to imagine, can do little against a political and social substance that is experiencing turbulence reminiscent of the years before the Second World War.

Perhaps we should focus more on this, both in Germany and in Italy.

Addendum 1. "Volksverhetzung”, crime of Hate Speech.

The crime of "Volksverhetzung" (Section 130 of the German Penal Code) complements the prohibition of symbols of anti-democratic and terrorist organizations. A very similar law regulates the same crime in Italy: the Mancino Law of 1993. Herein the English translation of the German section:

(1) Whoever, in a manner suited to causing a disturbance of the public peace,

1. incites hatred against a national, racial, religious group or a group defined by their ethnic origin, against sections of the population or individuals on account of their belonging to one of the aforementioned groups or sections of the population, or calls for violent or arbitrary measures against them or

2. violates the human dignity of others by insulting, maliciously maligning or defaming one of the aforementioned groups, sections of the population or individuals on account of their belonging to one of the aforementioned groups or sections of the population

incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term of between three months and five years.

(2) Whoever 1. disseminates content or makes it available to the public, or offers, supplies or makes available to a person under 18 years of age content which (a) incites hatred against one of the groups referred to in subsection (1) no. 1, sections of the population or individuals on account of their belonging to one of the groups referred to in subsection (1) no. 1, or sections of the population, (b) calls for violent or arbitrary measures against one of the persons or bodies of persons referred to in letter (a) or (c) attacks the human dignity of one of the persons or bodies of persons referred to in letter (a) by insulting, maliciously maligning or defaming them, or 2. produces, purchases, supplies, stocks, offers, advertises or undertakes to import or export content in order to use it within the meaning of no. 1 or to facilitate such use by another incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or a fine.

(3) Whoever publicly or in a meeting approves of, denies or downplays an act committed under the rule of National Socialism of the kind indicated in section 6 (1) of the Code of Crimes against International Law in a manner suited to causing a disturbance of the public peace incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years or a fine.

(4) Whoever publicly or in a meeting disturbs the public peace in a manner which violates the dignity of the victims by approving of, glorifying or justifying National Socialist tyranny and arbitrary rule incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or a fine.

Addendum 2. References and sources.

Rechtsextremismus: Symbole, Zeichen und verbotene Organisationen.

Right-wing extremism: Forbidden symbols, signs, and organizations (PDF)

The criminally punishable use of symbols of anti-constitutional and terrorist organizations § 86a StGB in the light of jurisprudence. (PDF)

Verbotsmaßnahmen. Overview of bans, Bundesverfassungschutz.

Verwenden von Kennzeichen verfassungswidriger und terroristischer Organisationen, (Using symbols of unconstitutional and terrorist organizations) Wikipedia DEU