8 May and 9 May 2025: Berlin, a mirror of our times.

PHOTO STORY A walk through Berlin's memorials on these historic dates—where memory and meaning collide.

When I started this blog, I had to ask myself what it was really about. Why call it Beyond Berlin? The first phrase that came to mind was: I write it because Europe can be seen better from Berlin.

Not because Berlin is more important than other cities. Not because more important things happen here—this week, for example, many hearts and minds were in Rome.

But because Berlin reflects. It reflects deeply—it thinks. And reflects as in mirrors—concentrates and returns, like a kaleidoscope, all that is Europe: Its stories, its sins, its contradictions. Its hopes. Its dreams and its nightmares.

At the end of a week so full of history—and future—I’m more convinced than ever. From here, you can really see Europe.

What did I see, in these days wrapped in remembrance? So much. Too much. A headache’s worth of images and emotions. I saw history return.

Concert halls. Auditoriums. Filled to capacity—for 8 May 1945. That didn’t happen a few years ago. Back then, it was only for history nerds like me. Or for those immersed in Erinnerungskultur. Which we thought was solid. Turns out, it’s not.

I saw young people. Elderly people. Old and new Germans. Curious faces. Confused ones, too. I saw volunteers bring memory back to life. Oral histories recovered. New tech used to keep those stories alive—for whoever comes next.

I saw new connections. Stories no one would have linked before: German refugees from the former Ostgebiete in 1945 whose stories intertwine with refugees´ stories from Ukraine. This is a continent built on displacement. Now we know.

I saw people remember that there was never a Stunde Null—no true “zero hour.” Survivors of forced labor and camps wandered for months, years, before they could rebuild. Berliners, too—photos from 1946, 1947 show a city barely surviving. Normality didn’t return before 1948 or ‘49.

And I felt it again—what you always feel here, this time of year. The ambiguity.

Two days, more meanings: May 8 and May 9. Capitulation. Liberation. Victory.

A promise. A trauma. A drawer slammed shut. Or left wide open.

A rabbinical saying tells us the Torah has seventy faces: interpretation is infinite. Tolerance for ambiguity—they understood it well. And we must live with it, too.

Two days a year, Berlin´s Soviet memorials here become—somehow—“theirs.” A space claimed by Russians and Russophiles. They bring pride, symbols, songs. And a nationalism that’s unsettling, and real.

The rituals are ambiguous. The black-and-orange St. George ribbons—homage to the fallen? Or a provocation? At Treptower Park, where Stalin’s words are carved in stone, where heroes and tyrants blur, where marble can’t speak for itself—what are we really honoring? The “German-Soviet friendship” of the GDR?

How deeply has this shaped East German mindsets? As deeply as the misleading equation of "Soviet" with "Russian"?

So deeply that those who call for peace really mean peace with Russia, rather than peace for Ukraine?

How much ambiguity can we endure in these days?

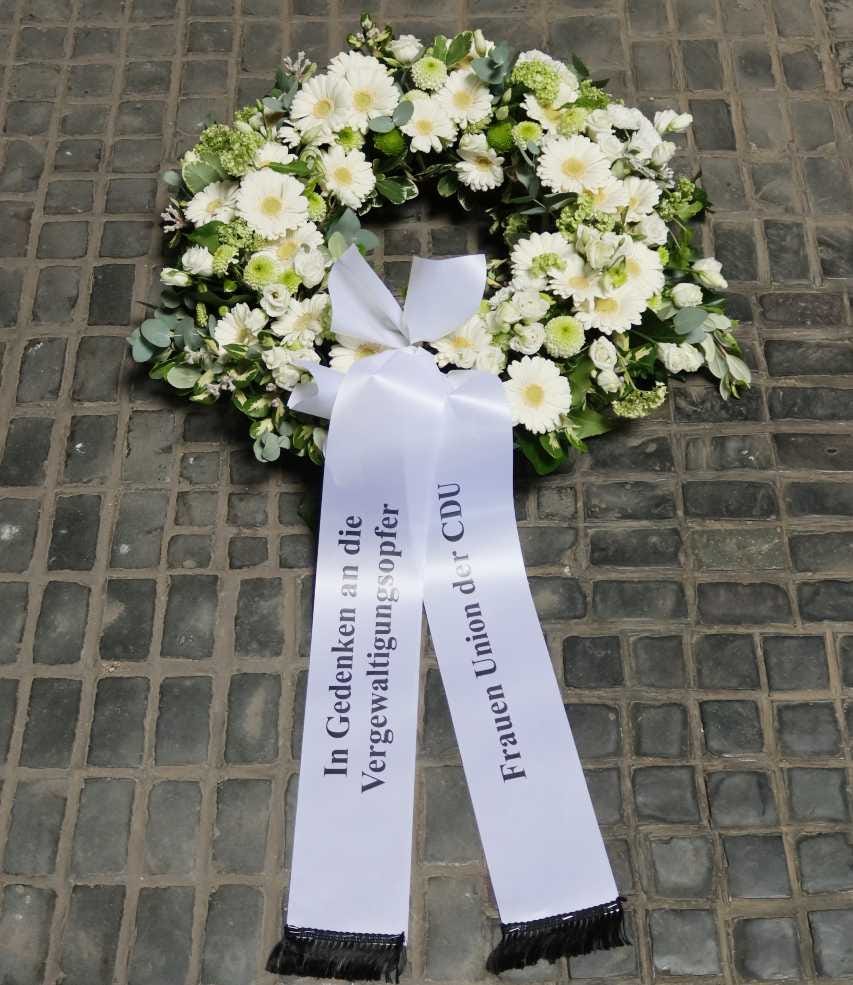

And then there’s the still too often unspoken history. The violence of victory. 100,000 women raped in Berlin in those days. At least. Do we celebrate? Do we grieve? This year, the Neue Wache filled with unexpected wreaths. A tribute to victims of Red Army sexual violence.

I've learned to live with it all. This mess of meanings. This multiplicity. That is why I keep going to these places: I take pictures, I listen, I even smile sometimes - when a group of women sing "Katyusha" under the giant Soviet soldier at the memorial in Treptower Park, or someone prints out verses of a Soviet patriotic song calling for a fight against the "dark fascist power". But who is the fascist now, in 2025?

Ambiguity. We have to live with it. But this year something changed. It wasn't just ambiguity. It was something darker. Not just confusion. Not just propaganda. Excited spirits. Energies waiting to explode. Today they sing. Tomorrow they will shoot?

In recent weeks, the Russian ambassador made uninvited, provocative appearances at Seelower Heights and Torgau. This foreshadowed what we would witness in Berlin.

We knew what to expect. Were these pure provocations—as the Ukrainian Embassy in Germany suggested when asking to exclude Russia from future celebrations—or something we cannot legally prevent, given that the Reunification Treaty formally acknowledges Russia as the heir of the Soviet Union?

Ambiguity pervades our recent history, our memory, and the podiums of ceremonies.

Ambiguity mixed with ignorance led to awkward situations at the Treptower Park Memorial: like when a young police officer, equipped with only a 12-page printout of banned words, portraits, and slogans, asked a member of the German Wagenknecht Party (BSW) to remove his neckerchief—blue and white striped with a red triangle in the middle—because she thought it resembled the Russian flag. In reality, it was the official neckerchief of the Association of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime: the blue and white stripes represent concentration camp uniforms, and the red triangle symbolizes the marker that SS officers used to identify political prisoners.

But the real story wasn't on the podium. It was down below. Amongst us. Treptower Park on 8 and 9 May was a mirror. A stage. A circus. A spirited carousel. A man took the microphone and declared the GDR to be the real Germany.

I walk on. Fake Don Cossacks strutted around me, their bags checked for safety. Elderly women held photos of their dead relatives. Red flags. Carnations. Roses.

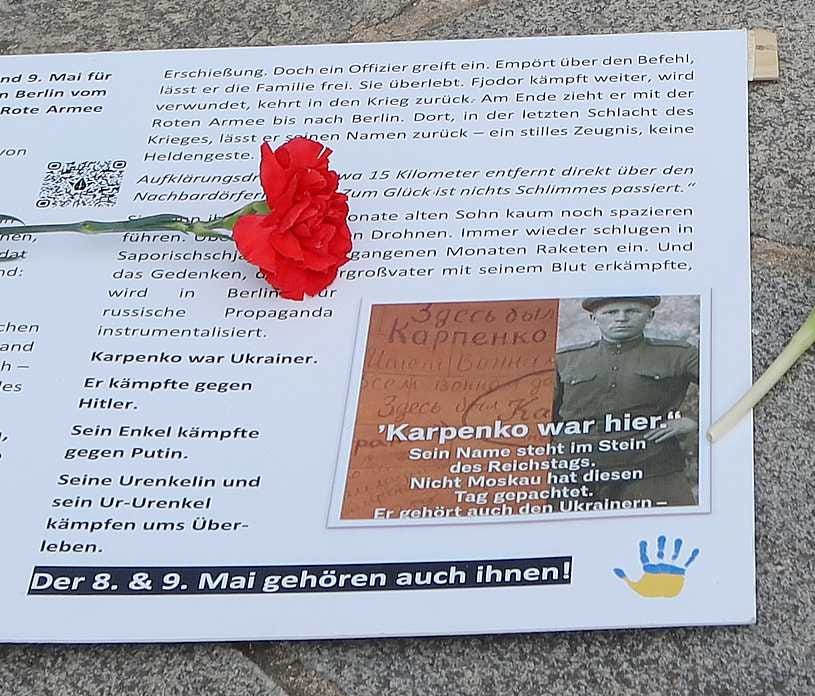

Women sang Russian patriotic songs, wielding them like weapons against the Ukrainian mourners before them, draped in blue and yellow. The Ukrainians tried to remind us: among the 7,000 fallen buried there, at least 1,000 were their countrymen. And many more fought here in Berlin in those days.

One of them was Fyodor Karpenko. He left his signature in the Reichstag. He defeated Hitler. His grandson died in 2024—because of Putin. And his great-grandson is growing up under bombs.

A few metres away, a NATO flag is wrapped around a Ukrainian one. A provocation? A statement? A symbol of resistance?

Then came the flags of free Belarus. Together with the flag of free Russia-white-blue-white and Ukraine.

Also from Palestine. These flags, like parsley, are everywhere in Berlin. They add flavour. They add fire. But sorry, they do not belong here. And in all this movement, in all this watching - trying to decipher symbols, to align loyalties, to understand languages - we forgot something.

The thousands of dead. Most of them nameless. Buried in mass graves. They might have liked the flowers. They might have liked the songs and the accordion music. They might have preferred silence.