Berlin, May 2, 1945: The surrender of a city and the final days of war in Europe.

In a modest Tempelhof apartment, Berlin's city surrender was signed—a crucial step toward Germany's final capitulation, as the shattered city began emerging from its ruins.

This weekend marked the start of Berlin's anniversary week — 80 years since the fall of Berlin and the fall of Nazism.

But there were no grand speeches. No fanfares. Small, quiet ceremonies to lay wreaths on the steps of memorials. New information boards were put up here and there. A pop-up exhibition opened in front of the Brandenburg Gate. Exhibitions opened in former prisons, camps and shadowy corners of the city — quietly. Even the evening news seemed unsure how to talk about it. A minute here. A headline there. And yet something remains. Perhaps this quiet is a shield — meant to protect these spaces from the noise of provocation, from the tensions I wrote about last time.

Or maybe it's something else. Perhaps, in this silence, Berlin is asking us to listen more carefully. Because here, in this city, every street corner from May 1945 has something to say — if we're willing to stand still long enough to hear it.

In a house in Tempelhof: at 8:23 on 2 May 1945.

Most visitors to Berlin know the house in Karlshorst—the site where Germany's highest military commanders signed the final act of surrender on the 8th of May, 1945. It's a well-preserved piece of history. A magnet for those drawn to the last pages of the Second World War.

But there's another place, far less known. Tucked away in the quiet, residential district of Tempelhof: the address is Schulenburgring 2. It is a bourgeois building, not luxurious, almost anonymous. Nothing suggests what happened there—unless you know where to look.

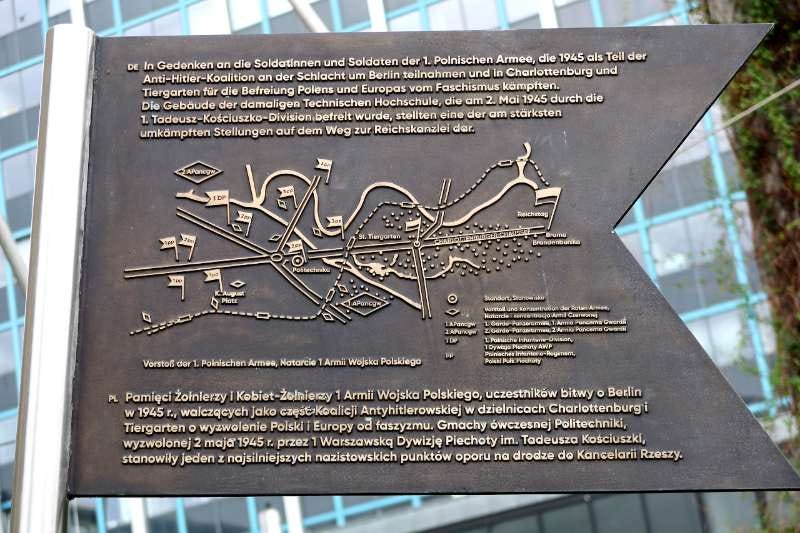

In the dining room of a ground-floor flat, between floral wallpaper and a cluttered map table, Soviet General Wassili Iwanowitsch Tschuikow had set up his command post. From April 27th to May 3th, it was from here that the Red Army coordinated its final push into Berlin.

And it was here, on the morning of May 2nd—at around eight o'clock—that Wehrmacht General Helmuth Weidling, commander of the Berlin Defence Area, formally surrendered the city to the Red Army. The Führer was already dead. The city was in flames. And at this unassuming address, history pivoted.

2-3 May 1945: The end of the Battle of Berlin.

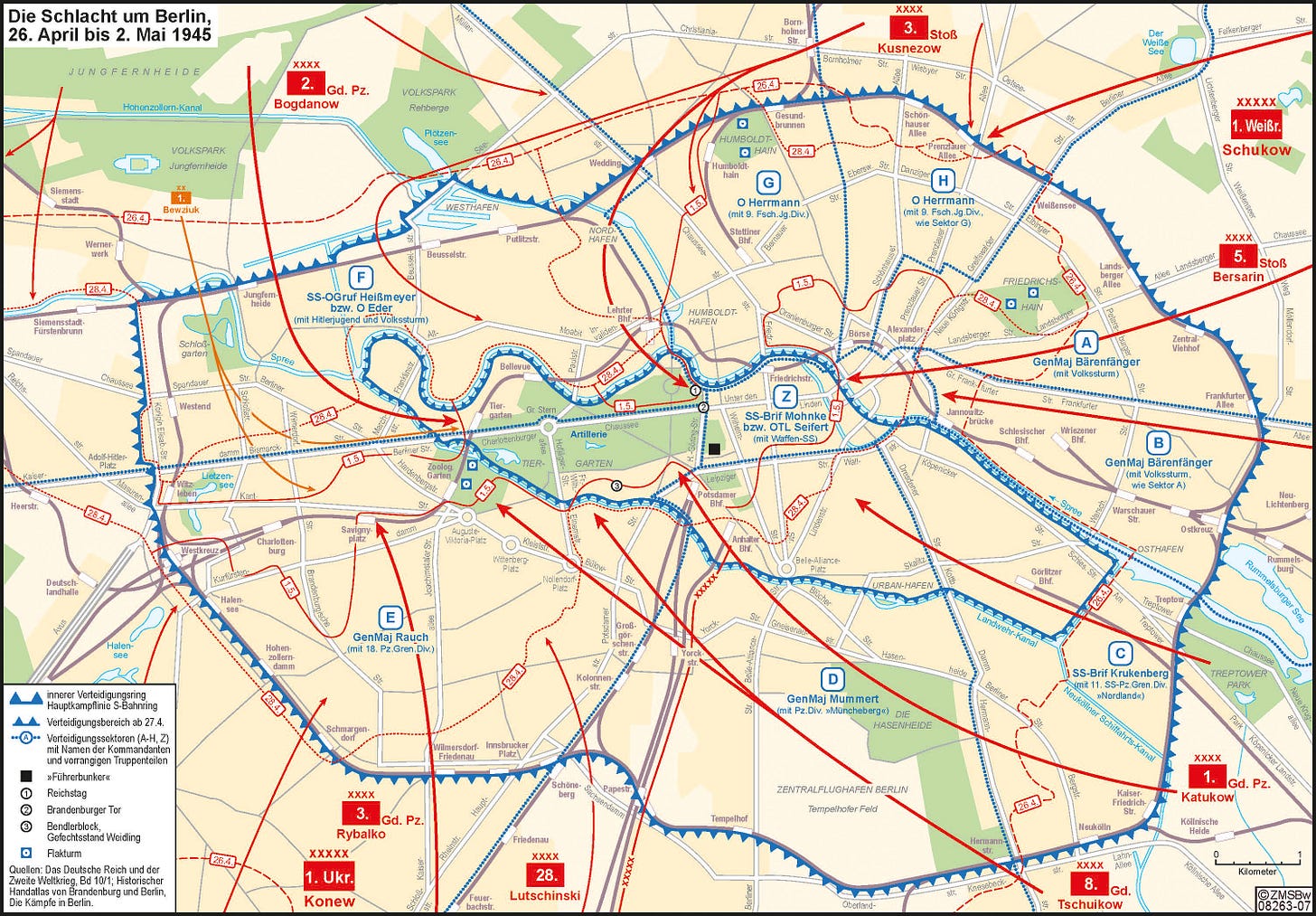

By April 25th, Berlin was surrounded. Soviet troops had closed the ring. Within two days, they were inside the city—pressing in from all directions. What followed was brutal: block-by-block, floor-by-floor, house-to-house fighting.

By April 27th, the German army held barely anything. The once-mighty Wehrmacht was reduced to a desperate, disjointed resistance. The war had collapsed into chaos. Berlin was a graveyard of buildings. Trapped beneath the Reich Chancellery, in the gloom of his bunker, Adolf Hitler took his own life on April 30th.

On the evening of May 1st, around 11:00 p.m., General Helmuth Weidling summoned what was left of Berlin’s command structure to the Bendlerblock—his final command post. There, he made the unthinkable official: the Führer is dead, and the only option left was surrender. A groan rippled through the men**.** Even those who had anticipated the end were devastated. There were no alternatives—the course was set.

Soon after midnight, between 12:50 and 1:50 a.m. on May 2nd, Greater German Radio in Masurenallee broadcast one last message to the nation:

“We greet all Germans and remember the brave German soldiers on land, at sea, and in the air. The Führer is dead—long live the Reich.”

Almost simultaneously, a German radio message—this one in Russian—was transmitted to the Soviet Army:

“Attention! Attention! This is the LVI. German Panzer Corps. We request a ceasefire. At 0:50 Berlin time, we will send parliamentarians to the Potsdam Bridge. Identification mark: white flag. Awaiting reply.”

The answer came swiftly:

“Understood! Understood! We will forward your request to our commander!”

Soviet General Tschuikov ordered a halt to hostilities at the designated point. He sent an officer and an interpreter to meet the German delegates. But his instructions were crystal clear: negotiate nothing. There would be no conditions, no deals. Only immediate and unconditional surrender.

Still, there were gestures of formality. The Germans were told that officers would be allowed to carry small sidearms—swords or daggers, but no pistols. Each man could take only what he could carry. The Soviets also promised to protect the civilian population and care for the wounded (a dark chapter that deserves its own telling—the violence Soviet forces inflicted on civilians, particularly women).

The Germans, for their part, explained that many units had no functioning communications. Messengers would need time—at least three or four hours—to reach them. So the ceasefire was scheduled for 6:00 a.m.

Around 3:00 a.m., the German envoys returned to the Bendlerblock and informed Weidling and his staff of the Soviet terms. By 5:30, they abandoned the command post and gave themselves up. General Weidling was taken to that modest flat in Tempelhof—Schulenburgring 2—where, in less than thirty minutes, the surrender of Berlin was formalized.

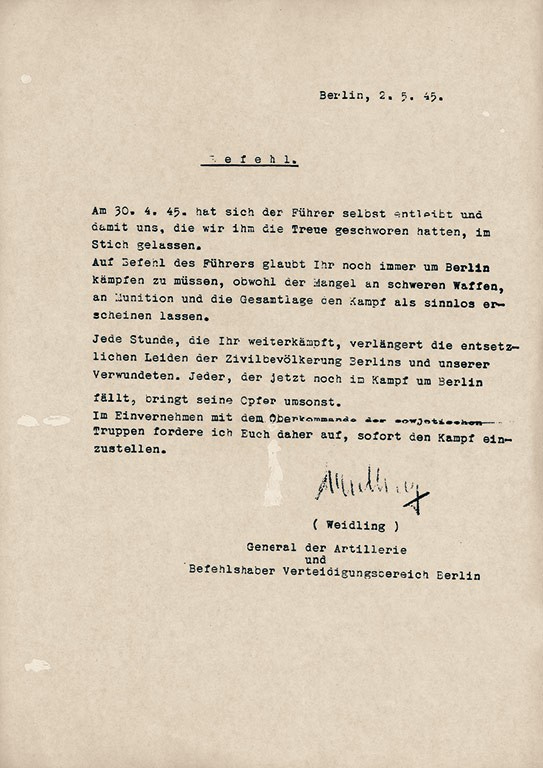

Weidling then composed a final order—typed by a 20-year-old Soviet Army interpreter named Stefan Doernberg. Doernberg had fled Nazi Germany with his Jewish family in 1935 and joined the Red Army after the invasion in 1941. Now, in the final moments of the war, he was the one recording its end.

Berlin, May 2, 1945.

Order!

On April 30, 1945, the Führer himself took his own life and thereby abandoned us, who had sworn loyalty to him.

On the Führer's orders, you still believe you must fight for Berlin, although the lack of heavy weapons, of ammunition, and the overall situation make the fight appear senseless.

Every hour that you continue fighting prolongs the terrible suffering of the civilian population of Berlin and our wounded. Everyone who falls now in the battle for Berlin renders his sacrifice futile.

In agreement with the High Command of the Soviet troops, I therefore order you to cease fighting immediately.

Signed: Weidling

General of Artillery and Commander of the Berlin Defense Area

This message was recorded and broadcast across the ruined city—carried by loudspeaker trucks rumbling through rubble, announcing the end.

2-3 May: Reemerging from the ruins.

Despite the city surrender, fighting flared up in pockets of Berlin throughout May 2nd. SS units resisted bitterly. But by 5:00 p.m., a final ceasefire had come into effect. Across the ruins of the capital, the last fragments of the defeated Wehrmacht emerged from the shadows and began their long march into captivity.

Slowly, hesitantly, the Berliners crept out of their cellars—gaunt and dazed, eyes adjusting to the broken daylight. They had survived days without water, gas, or electricity, crammed underground as the city above them burned and fell.

They found devastation everywhere. The air hung heavy with smoke. Fires still crackled in the distance. Whole streets had vanished under mountains of rubble. Corpses—of soldiers, horses, civilians—lay unburied among the ruins. Twisted metal, burned-out tanks, and shattered trams lined the boulevards like broken bones.

Then came the looting.

Shops, food depots, warehouses—everything was ransacked. The Schultheiß Brewery in Prenzlauer Berg, today the sleek Kulturbrauerei, was overrun. From its bunkers poured men, women, and children, carrying sacks of margarine, tins of meat, soap, biscuits, bread, wine, and chocolate. Some Russian soldiers fired warning shots into the air to push the crowd back. But hunger, and desperation, were stronger than fear.

Of the much-trumpeted Volksgemeinschaft—the so-called national community—nothing remained. That had always been more myth than reality. Now, it was every man, woman, and child for themselves. People clawed, pushed, shouted, snatched what they could. Civilization, like the city, had cracked.

And yet. At some point, the silence came.

No more artillery. No more bombers. No more sirens. Berliners, incredulous, began to sleep in their beds again—undressed. The rubble was still there. But already, some were sweeping the sidewalks.

For the Soviet soldiers, May 2nd was a day of triumph. Writer Vasily Grossman, reporting from Berlin, described how the tanks sank into a sea of red flags and flowers. People danced. They sang. Gunfire rang out—not in battle this time, but in joy. “I slept like I hadn’t in years,” he wrote. “Like a dead man.”

That same evening, the BBC interrupted its programming with breaking news: in Italy, German Army Group C had surrendered. Six hundred thousand men laid down their arms. It had happened on April 29, while Hitler was still alive—though he never knew.

But the war was not over yet.

Berlin had fallen. The capital was quiet.

But it would take six more days—until May 8—for Europe to breathe again.

The Last Week of the Third Reich.

The air waves pulsed with the bombastic notes of Wagner. It was 1 May 1945, and Radio Hamburg was making a grand announcement, punctuated not by news reports but by excerpts from Tannhäuser and Götterdämmerung.

Thank you. Great description of the fall of Berlin, and especially the specifics-the first I’ve read. We don’t hear the German perspective of the war often.